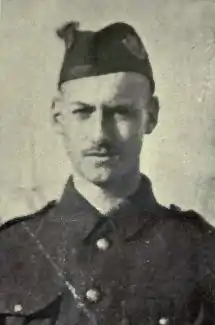

Frederick Fisher (soldier)

Frederick Fisher VC (3 August 1894 – 23 April 1915), was a Canadian recipient of the Victoria Cross (VC), the highest and most prestigious award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forces.

Frederick Fisher | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 3 August 1894 St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada |

| Died | 23 April 1915 (aged 20) † St Julien, Ypres salient, Belgium |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Canadian Expeditionary Force |

| Years of service | 1914–1915 |

| Rank | Lance-Corporal |

| Unit | 13th Battalion, CEF |

| Battles/wars | First World War |

| Awards | Victoria Cross |

A soldier with the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) during the First World War, he was posthumously awarded the VC for his actions on 22 April 1915, during the Second Battle of Ypres. His VC was the first to be earned by a Canadian while serving in the CEF.

Early life

Born in St. Catharines, Ontario, on 3 August 1894, Fredrick Fisher was one of four children of a bank manager and his wife. He attended schools in Niagara, Dunneville and Montreal, as his father moved for work. In 1912, he enrolled at McGill University in Montreal to study engineering. While at McGill he joined Zeta Psi Fraternity. He did well academically but was also a keen athlete; he was a member of the university's track team.[1]

First World War

On the outbreak of the First World War, Fisher enlisted in the 5th Regiment of the Royal Highlanders. He sailed for England aboard Alaunia with other contingents of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF), arriving there on 15 October 1914. By this time, he had been posted to the regiment's 13th Battalion. For the next few months, the battalion underwent training on the Salisbury Plains, during which time Fisher was promoted to lance corporal. In March 1915, the battalion departed for the Western Front.[1]

As part of 3rd Brigade, 1st Canadian Division, Fisher's battalion was stationed near St. Julien in the Ypres Salient, with the French 45th Division, made up of Moroccan troops on its left.[2] To open the Second Battle of Ypres, on the evening of 22 April 1915, near St Julien, Belgium, the Germans released poison gas, the first instance of chemical warfare. Caught by surprise, the Moroccans to the left of the Canadians retreated. After a short pause to wait for the gas to clear, the Germans launched an attack into the gap, while the British and Canadians desperately tried to establish a new defence line.[3] A Canadian artillery battery of 18 pounders was firing on the German trenches when its commander became aware of German troops moving in the open towards his position and requested infantry support. Soldiers of the 14th and 15th Battalions were sent forward along with a machine-gun squad commanded by Fisher. Under heavy fire, he covered the retreat of the battery, losing four men in the process. His actions allowed for the battery to initially remove the immediate threat posed by the Germans and continue firing and then for its guns eventually hauled to safety later in the evening. Early the next morning, 23 April, when Fisher had obtained four more men from the 14th Battalion, he went forward again into St. Julien to fire on the swarming Germans. Meanwhile, the 13th Battalion positioned on the extreme left of the Canadian Division's sector was under heavy fire. Fisher set up his gun at another position to attack the oncoming Germans and was subsequently killed while yet again bringing his machine gun into action under very heavy fire.[2]

Fisher was awarded the Victoria Cross (VC) for his actions on 22 April 1915.[2] The VC, instituted in 1856, was the highest award for valour that could be bestowed on a soldier of the British Empire[4] and Fisher was the first Canadian recipient from the CEF to earn the award.[1] The citation that was published in the London Gazette for his VC read:

On 23rd April, 1915, in the neighbourhood of St. Julien, he went forward with the machine gun, of which he was in charge, under heavy fire, and most gallantly assisted in covering the retreat of a battery, losing four men of his gun team. Later, after obtaining four more men, he went forward again to the firing line and was himself killed while bringing his machine gun into action under very heavy fire, in order to cover the advance of support.

— The London Gazette, 22 June 1915[5]

The citation refers to 23 April 1915; this is likely an error as his actions in covering the withdrawal of the artillery battery were performed on 22 April.[2] Like many of the other Canadian soldiers who fell in the first three days of the Second Battle of Ypres, Fisher's body was never recovered. His name can be found on the Menin Gate war memorial in Ypres[1] for the 56,000 troops from Britain, Australia, Canada and India killed in the Ypres Salient and who have no known grave.[6]

Victoria Cross

In August 1915, the War Office forwarded Fisher's VC to his parents, who were living in Westmount,[1] and accompanied by a handwritten letter from King George V.[7] The following year, they attended a ceremony at McGill University where a portrait of Fisher was unveiled. Following the death of Fisher's mother in 1946, the VC was passed on to his sister, who in turn donated it to the Royal Highland Regiment of Canada,[1] now known as the Black Watch. The VC is securely held in a bank vault while a replica is displayed at its headquarters in Montreal.[7]

Fisher is remembered by two plaques; the first, laid in 1917, is at the Royal Highlanders of Canada Armories in Montreal, while the other, laid in 1970 by the Royal Canadian Legion, is in Memorial Park at St. Catharines, his town of birth.[1]

References

- Batchelor & Matson 2011, pp. 92–93.

- Batchelor & Matson 2011, pp. 90–91.

- Batchelor & Matson 2011, p. 88.

- Ashcroft 2007, pp. 8–10.

- "No. 29202". The London Gazette (Supplement). 22 June 1915. pp. 6115–6116.

- "Ypres (Menin Gate) Memorial". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- Montpetit, Jonathan; Nakonechny, Simon (4 November 2018). "Montreal's Black Watch regiment treasures WW I Victoria Cross". CBC/Radio-Canada. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

Bibliography

- Ashcroft, Michael (2007) [2006]. Victoria Cross Heroes. London: Headline Review. ISBN 978-0-7553-1633-5.

- Batchelor, Peter; Matson, Christopher (2011). The Western Front 1915. VCs of the First World War. Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-6057-4.

- Buzzell, Nora, ed. (1997). The Register of the Victoria Cross. Cheltenham, Gloucestershire: This England Alma House. ISBN 0-906324-27-0.