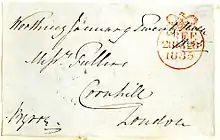

Free frank

A free frank was a mark applied by means of a hand-stamp to parliamentary mail in Britain to indicate that the mailed item did not require postage. The privilege of free franking was granted to four different classes: Members of Parliament; peers sitting in the House of Lords; office-holders, largely as stipulated by Acts of Parliament; and to archbishops and bishops sitting in the House of Lords. Requirement for free franking were that the mailed cover (letter or packet) had to be signed by the official sender. As a result, free franks were avidly sought during the first three decades of the nineteenth century for autograph collections. This was accomplished by cutting out the front panels of the envelope which carried the inscriptions which were required under the use of this privilege. These panels are referred to by collectors as free fronts.

In 1840 as a result of various abuses and excesses that had plagued the British Post office for many years, Rowland Hill's reforms brought an end to the free franking privilege in 1840 when he introduced the postage stamp to Britain.[1]

Origins and use

Under the Parliamentary Franking System, members of the British Parliament (MPs) were able to send letters free of charge, the cost being borne by the taxpayer. The origin of the system was a decree of the Council of State of 1652[2] confirmed by an ordinance of 2 September 1654[3] during the Cromwellian period. Letters that were "for the service of the Commonwealth" were free of charge.[4] Originally all that appeared on letters was the addressee, the word Frank or Free and the signature or seal of the sender. In the eighteenth century special marks started to be used, first in Dublin in 1706, and later in London and Edinburgh. The date of posting was introduced and more elaborate marks came into use.

Abuses

The privilege was supposed to be for official business, however, the high cost of postage meant that it was widely abused. MPs sold their frank to businesses and franked the letters of constituents and relatives. Regulations about the number and weight of letters and other matters failed to stop the abuse of the system. According to Ralph Allen, in 1741 the value of franked letters, if the correct postage had been charged, was over £50,000 and by the time of Allen's death in 1764 the annual value was £170,000.[5]

In 1840 one of the reforms introduced by Rowland Hill was the elimination of the free franking privilege granted to members of parliament and other government officials. It was common for members of parliament to give out signed blank sheets of paper to friends and business associates on which they could write letters and mail them at no cost. Parliament members were even appointed to the boards of large companies in order that their mailings could make use of the free franking privilege.[6]

Although free franking existed from the middle of the seventeenth century, it was not until 1764, when the Post Office revenues passed from the Crown to the State, that the first handstamp was introduced in England.

In 1764 an Act of Parliament was passed to prevent abuses which included a penalty of transportation for seven years for anyone convicted of counterfeiting hand writing in order to send mail free of postage.[7] By the 1830s around five million franks were used annually.[8] The system eventually ended with the introduction of the Uniform Penny Post in 1840.

Collecting

Free Frank marks are often found on early pre-stamp mail and are collected by philatelists and postal historians.

International

Similar systems have been introduced in other countries. For instance, U.S. Congressmen are able to send mail free of charge by applying their signature, or frank, and the term "free frank" has been adopted for many different marks on mail indicating that no postage is to be charged. The President does not have the privilege; however, the Vice President as President of the Senate may use his signature to frank mail.

See also

References

- "The Carlow County, Members Of Parliament, Free Franking privilege". County Carlow Genealogy IGP. Archived from the original on 22 August 2019. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- Alcock R.C. & Holland F.C. British Postmarks: A Short History and Guide, R.C. Alcock Ltd., Cheltenham, 1977, p. 53.

- Robinson, Howard. The British Post Office: A History, Princeton University Press, New Jersey, 1948, p. 44.

- Robinson, p. 113.

- Robinson, p. 116

- "The Free Franking Privilege". Warwick and Warwick. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- Robinson, p. 117.

- Robinson, p. 288.

Further reading

- Brumell, George. A Short Account of the Franking System in the Post Office, 1652–1840, The Bournemouth Guardian, 1936.

- Lovegrove, J.W. Herewith My Frank, published by the author, 2nd Ed. 1989.

- Scott, J.G.S. Official franking 1800–1840, The Postal History Society, London, 1983. ISBN 0-85377-015-8.

- Bottomley, Frank. The franking system in the Post Office 1652–1840, The Society of Postal Historians, 1988.