Freels Farm Mounds

The Freel Farm Mound Site (40AN22)[1] (formerly 7AN22)[freelfarm 1] is an archaeological site and burial mound of the Woodland cultural period located on the Oak Ridge Reservation in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. The site was excavated in 1934 as part of the Norris Basin Survey by the Tennessee Valley Authority using labor from the Civil Works Administration under the supervision of T.M.N. Lewis. Important finds of the excavation include 17 burials and a few artifacts. The artifacts and records from the fieldwork are held by the McClung Museum in Knoxville, Tennessee.

Location within Tennessee today | |

| Location | Oak Ridge, Tennessee, Anderson County, Tennessee, |

|---|---|

| Region | Anderson County, Tennessee |

| Coordinates | 35°58′24″N 84°13′06″W |

| History | |

| Cultures | Late Woodland period |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1934 |

| Archaeologists | William S. Webb, T.M.N. Lewis, A.P. Taylor |

| Architecture | |

| Architectural styles | burial mound |

| Responsible body: Tennessee Valley Authority, Civil Works Administration, Federal Relief Administration | |

Site description

The Freel Farm Mound is located on the U.S. Department of Energy's Oak Ridge Reservation. The site is currently inundated by Melton Hill Lake.[freelfarm 2] At the time of excavation the mound was located on the William Freel farm 2 miles southeast of Scarboro, Tennessee.[freelfarm 3] The site was located 1200 feet from the western side of the Clinch River in a wide valley with ridges to the east and west[freelfarm 3] in a prominently wooded knoll.[freelfarm 4] During the excavation the mound resided on land that had been owned by the Freel family for over 135 years.[freelfarm 3] The field surrounding the mound had been traditionally farmed; however the mound itself had never been disturbed. Webb described the mound as covered with undergrowth and having eight large trees growing from it.[freelfarm 3] The largest tree was a white oak that measured 23 inches in diameter.[freelfarm 3] The roots from the trees had extensively penetrated the mound.[freelfarm 3] A part of the mound on the western side had been removed to create a dirt road.

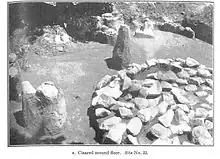

The mound was circular shaped with a diameter of 40 feet and a height of eight feet above the original ground surface at its midpoint.[freelfarm 3] It was created from hard-packed yellow clay with small specs of charcoal inside.[freelfarm 3] The mound had one indication of a grave excavation below the original forest ground level near the center of the mound.[freelfarm 3] In this grave was "Burial No. 17", the body had been covered by large stones.[freelfarm 3]

The stone pile was stacked to form a circular shape that measured 16 feet and 4 inches in diameter and rose above the original ground surface approximately 1 foot.[freelfarm 3] "Burial No. 17" and the stone circle made up the original increment of the construction site.[freelfarm 3] The earth on top of the stones was added as additional bodies were interred into the mound.[freelfarm 3]

The mound is associated with the Late Woodland period and was likely created between 500-1000 CE.[freelfarm 4] The basis of this assessment is related to the burial practices of the individuals within the mound.[freelfarm 4] The differences in the mortuary treatment of individuals at Freel Farm mound indicate a non-egalitarian society had formed.[freelfarm 5]

Recent history of the site

Freel Farm mound was excavated in 1934 due to its location in the Norris reservoir basin project area. In the 1930s as Norris Dam was being constructed the Tennessee Valley Authority sponsored an archaeological survey of the Norris basin. The survey had three key goals; the discovery of all prehistoric sites within the basin, the excavation of all sites found, the recovery and preservation of all information and material of archaeological value.[freelfarm 3] The survey found 23 sites of prehistoric significance. Freel Farm mound was the 22nd site. The location of the mound was actually downstream of Norris Dam and would not have been affected by the collecting waters, but was excavated due to its proximity to the basin.[freelfarm 4]

The Tennessee Valley Authority, along with the Civil Works Administration, and the Federal Relief Administration hired T.M.N. Lewis to oversee the archaeological survey. Lewis served as a district supervisor on the excavation of the site and A.P. Taylor served as the field supervisor.[freelfarm 3]

In the 1960s the construction of the Melton Hill Dam to the south of Oak Ridge, Tennessee caused the water levels along the Clinch River to rise permanently submerging the Freel Farm mound.[freelfarm 4]

Excavation

The mound was staked into 5-foot squares, along the cardinal directions.[freelfarm 3] The northeastern stake was designated as the zero stake.[freelfarm 3] The squares were designated southward by integers and westward by decimals.[freelfarm 3] Stratification was not discernible and there was no evidence of intrusion.[freelfarm 3] Care was taken to maintain vertical profiles every five feet and to keep a clean floor in the trench going down to the hardpan.[freelfarm 3]

The excavation revealed no evidence of midden material.[freelfarm 3] Also no potsherds were found in the mound.[freelfarm 3] There was no evidence on the site of any structures and very little information that would give any information as to who built the mound.[freelfarm 3] The burials and the stacked stone circle were the outstanding features discovered in the mound.[freelfarm 3] It was also determined during the excavation that the yellow clay used to cover the mound was clean and brought in to cover the bodies laid on the surface.[freelfarm 3]

Burials

17 burials were found within the mound.[freelfarm 3] Webb numbered the burials in the order in which they were found.[freelfarm 3]

- Burial No. 1: Fully flexed adult. The preservation of material is poor. A piece of drilled conch shell was found near the neck of the skeleton.[freelfarm 3]

- Burial No. 2: Partially flexed adult on the ground floor.[freelfarm 3]

- Burial No. 3: Poorly preserved partially flexed adult on the ground floor.[freelfarm 3]

- Burial No. 4: Eleven inches below the mound surface a poorly preserved partially flexed skeleton.[freelfarm 3]

- Burial No. 5: Greatly decayed bones on the ground surface.[freelfarm 3]

- Burial No. 6 and Burial No. 7: Portions of three bodies, two adults and one child. Poor preservation of the bones was due to the action of the roots of the trees.[freelfarm 3]

- Burial No. 8: Poorly preserved portion of a skull and the lower limbs of a fully flexed adult found 22 inches above the ground floor.[freelfarm 3]

- Burial No. 9: Found just below the mound surface was a nearly disintegrated adult. A flint spear point was also found.[freelfarm 3]

- Burial No. 10: A crushed skull found 10 inches above the ground floor beneath the base of a tree.[freelfarm 3]

- Burial No. 11: Poorly preserved skull, clavicle, and rib of an adult found 20 inches above ground floor.[freelfarm 3]

- Burial No. 12: Poorly preserved adult found 18 inches above the ground floor.[freelfarm 3]

- Burial No. 13: A bundle burial not in anatomical order.[freelfarm 3]

- Burial No. 14: Poorly preserved and partially disturbed adult found 15 inches above the ground floor. Some of the remains are not in anatomical order. A rock was placed over the leg bones.[freelfarm 3]

- Burial No. 15: A bundle burial not in anatomical order.[freelfarm 3]

- Burial No. 16: Crushed skull on the ground floor. Found near a perforated shell bead.[freelfarm 3]

- Burial No. 17: The best preserved and the original skeleton that was placed in the mound.[freelfarm 3] This skeleton was the only one in good enough condition to be studied and measured by W.D. Funkhouser, a physical anthropologist from the University of Kentucky.[freelfarm 6] Funkhouser took the measurements from Burial No. 17 and compared them with measurements from other individuals found during the Norris Basin Survey.

Freel farm mound site drawing.

Freel farm mound site drawing. Freel farm mound floor.

Freel farm mound floor. Freel farm mound stone circle.

Freel farm mound stone circle.

See also

Selected books, monographs, and papers

- Administration, U. D. (2006). Findings of No Significant Impact and Final Environmental Assessment for the Y-12 Potable Water System Upgrade. Oak Ridge, TN: U.S. Department of Energy.

- Webb, W. S. (1938). Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 118: An Archaeological Survey of the Norris Basin in Eastern Tennessee. Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Fielder, G. F. (1974). Archaeological Survey with Emphasis on Prehistoric Sites of the Oak Ridge Reservation Oak Ridge Tennessee. Oak Ridge, TN: Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

- DuVall, G. D. (1994). An Archaeological Reconnaissance and Evaluation of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge Reservation, Anderson and Roane Counties, Tennessee. Nashville: DuVall & Associates, Inc. Cultural Resources and Environmental Services.

- Funkhouser, W. (1938). A Study of the Physical Anthropology and Pathology of the Osteological Material From the Norris Basin. In W. S. Webb, Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 118: An Archaeological Survey of the Norris Basin in Eastern Tennessee. Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

References

- Administration, U.S. Department of Energy: National Nuclear Security (2006). Findings of No Significant Impact and Final Environmental Assessment for the Y-12 Potable Water System Upgrade. Oak Ridge, TN: U.S. Department of Energy.

- Webb, William S. (1938). Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 118: An Archaeological Survey of the Norris Basin in Eastern Tennessee. Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Fielder, George F Jr. (1974). Archaeological Survey with Emphasis on Prehistoric Sites of the Oak Ridge Reservation Oak Ridge Tennessee (PDF). Oak Ridge, TN: Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

- Webb, W. S. (1938). Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 118: An Archaeological Survey of the Norris Basin in Eastern Tennessee. Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Fielder, G. F. (1974). Archaeological Survey with Emphasis on Prehistoric Sites of the Oak Ridge Reservation Oak Ridge Tennessee. Oak Ridge, TN: Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

- DuVall, DuVall (1994). An Archaeological Reconnaissance and Evaluation of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge Reservation, Anderson and Roane Counties, Tennessee (PDF). Nashville, TN: DuVall & Associates, Inc. Cultural Resources and Environmental Services.

- Funkhouser, W.D.; Webb, William S. (1938). Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 118: An Archaeological Survey of the Norris Basin in Eastern Tennessee. Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

External links

- http://www.ornl.gov/info/reports/1974/3445603172117.pdf Archaeological Survey with Emphasis on Prehistoric Sites of the Oak Ridge Reservation Oak Ridge Tennessee.

- http://www.osti.gov/bridge/servlets/purl/10121935-HPyu6I/native/10121935.pdf An Archaeological Reconnaissance and Evaluation of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge Reservation, Anderson and Roane Counties, Tennessee.

- http://energy.gov/sites/prod/files/nepapub/nepa_documents/RedDont/EA-1548-FEA-2006.pdf Findings of No Significant Impact and Final Environmental Assessment for the Y-12 Potable Water System Upgrade.