Freemium

Freemium, a portmanteau of the words "free" and "premium", is a pricing strategy by which a basic product or service is provided free of charge, but money (a premium) is charged for additional features, services, or virtual (online) or physical (offline) goods that expand the functionality of the free version of the software.[1][2] This business model has been used in the software industry since the 1980s. A subset of this model used by the video game industry is called free-to-play.

Origin

The business model has been in use for software since the 1980s. The term freemium to describe this model appears to have been created much later, in response to a 2006 blog post by venture capitalist Fred Wilson summarizing the model:[3]

Give your service away for free, possibly ad supported but maybe not, acquire a lot of customers very efficiently through word of mouth, referral networks, organic search marketing, etc., then offer premium-priced value-added services or an enhanced version of your service to your customer base.

Jarid Lukin of Alacra, one of Wilson's portfolio companies, then suggested the term "freemium" for this model.

In 2009, Chris Anderson published the book Free, which examines the popularity of this business model. As well as for traditional proprietary software and services, it is now also often used by Web 2.0 and open source companies.[4] In 2014, Eric Seufert published the book Freemium Economics, which attempts to deconstruct the economic principles of the freemium model and prescribe a framework for implementing them into software products.[5]

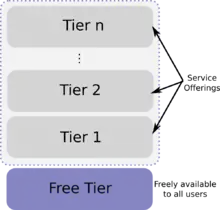

The freemium model is closely related to tiered services. Notable examples include LinkedIn,[6] Badoo,[7] Discord,[8] and in the form of a "soft" paywall, such as those employed by The New York Times[9] and La Presse+.[10] This is often in a time-limited or feature-limited version to promote a paid-for full version. The model is particularly suited to software as the cost of distribution is negligible.

A freemium model is sometimes used to build a consumer base when the marginal cost of producing extra units is low. Thus little is lost by giving away free software licenses as long as significant cannibalization is avoided. Other examples include free-to-play games – video games that can be downloaded without paying. Video game publishers of free-to-play games rely on other means to generate revenue – such as optional in-game virtual items that can be purchased by players to enhance gameplay or aesthetics.

Types of product limitations

Ways in which the product or service may be limited or restricted in the free version include:[11]

- Limited features: A free video chat client may not include three-way video calling. Most free-to-play games fall into this category, as they offer virtual items that are either impossible or very slow to purchase with in-game currency but can be instantly purchased with real-world money.

- Limited capacity: For example, SQL Server Express is restricted to databases of 10 GB or less.

- Limited use license: For example, most Autodesk or Microsoft software products with full features are free for students with an educational license. (See: Microsoft Imagine.) Some apps, like CCleaner, are free for personal use only.

- Limited use time: Most free-to-play games permit the user to play the game consecutively for a limited number of levels or turns; the player must either wait a period of time to play more or purchase the right to play more.

- Limited support: Priority or real-time technical support may not be available for non-paying users. For example, Comodo offers all its software products free of charge. Its premium offerings only add various kinds of technical support.

- Limited or no access to online services that are only available by purchasing periodic subscriptions

Some software and services make all of the features available for free for a trial period, and then at the end of that period revert to operating as a feature-limited free version (e.g. Online Armor Personal Firewall). The user can unlock the premium features on payment of a license fee, as per the freemium model. Some businesses use a variation of the model known as "open core", in which the unsupported, feature-limited free version is also open-source software, but versions with additional features and official support are commercial software.[12]

Significance

In June 2011, PC World reported that traditional anti-virus software had started to lose market share to freemium anti-virus products.[13] By September 2012, all but two of the 50 highest-grossing apps in the Games section of Apple's iTunes App Store supported in-app purchases, leading Wired to conclude that game developers were now required to choose between including such purchases or foregoing a very substantial revenue stream.[14] Beginning in 2013, the digital distribution platform Steam began to add numerous free-to-play and early-access games to its library, many of which utilized freemium marketing for their in-game economies. Due to criticism that the multiplayer games falling under this category were pay-to-win in nature or were low-quality and never finished development, Valve has since added stricter rules to its early-access and free-to-play policies.[15]

Criticism of freemium games

Freemium games have come under criticism from players and critics. Many are labelled with the derogatory term 'pay-to-win', which criticizes freemium games for giving an advantage to players who pay more money, as opposed to those who have more skill.[16][17] Criticisms also extend to the way that the business model can often appear unregulated, to the point of encouraging prolific spending. Freemium games are often designed in a manner where players who are not actively using premium features are actively frustrated, delayed or require much larger investments in time required to acquire currency or upgrades.

In November 2014, the animated TV series South Park aired an episode entitled "Freemium Isn't Free". The episode satirized the business model for encouraging predatory game design tactics based on an improper business model.[18] In 2015, Nintendo released two of their own freemium games in the Pokémon series based on other standalone purchasable titles.[19][20] With the title Pokémon Rumble World, Nintendo took a different approach by making it possible to complete the entire game without buying premium credits, but retaining them as an option so players can proceed through the game at a pace that suits them.[20]

See also

References

- JLM de la Iglesia, JEL Gayo, "Doing business by selling free services". Web 2.0: The Business Model, 2008. Springer

- Tom Hayes, "Jump Point: How Network Culture is Revolutionizing Business". 2008. Page 195.

- Schenck, Barbara Findlay (February 7, 2011). "Freemium: Is the Price Right for Your Company?". Entrepreneur. Retrieved 2018-01-09.

- Heires, Katherine (2006-10-01). "Why It Pays to Give Away the Store". CNN Money. Business 2.0 Magazine. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

- "I wrote Freemium Economics to encourage better F2P games not more, says Eric Seufert". PocketGamer. Steel Media. 2014-02-07. Retrieved 2014-09-04.

- Barr, Alistair (2011-09-11). "'Freemium' approach attracts venture capital". The Montreal Gazette. Postmedia Network Inc. Retrieved 2013-08-13.

- "What Is Discord Nitro, and Is It Worth Paying For?". 2020-05-06. Retrieved 2021-09-17.

- Chittum, Ryan (2011-07-22). "The NYT Paywall Is Out of the Gate Fast". Columbia Journalism Review. Retrieved 2011-12-07.

- Owen, Laura Hazard (2011-09-06). "Three More Papers Put Up Paywalls, With Some New Twists". paidcontent.org. Gigaom. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

- Kincaid, Jason (2009-10-24). "Startup School: Wired Editor Chris Anderson On Freemium Business Models". Techcrunch. AOL, Inc. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

- Wasserman, Anthony I. (2011). "How the Internet transformed the software industry". Journal of Internet Services and Applications. 2 (1): 11–22. doi:10.1007/s13174-011-0019-x. ISSN 1867-4828.

Some companies have only a single version of their software, while others follow an "open core" model, providing a community release of the core version, and offering proprietary premium features us- ing a commercial license.

- Dunn, John E. (2011-06-07). "Free Antivirus Programs Rise in Popularity, New Survey Shows". PC World. IDG Consumer & SMB. Retrieved 2011-06-12.

- "iOS Game Developers Must Choose: Sell Digital Currency or Lose Money". Wired. 26 September 2012. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- Gera, Emily (2014-11-21). "Valve adds new rules to Steam Early Access to ensure games don't suck". www.polygon.com. Polygon. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- "Most freemium games are pay to win - The Pub at MMORPG.COM - General Discussion Forums at". Mmorpg.com. Retrieved 2013-08-12.

- Makuch, Eddie (2013-03-15). "EA: freemium is 'where things are going' - GameSpot.com". Uk.gamespot.com. Archived from the original on 2013-07-08. Retrieved 2013-08-12.

- Grubb, Jeffrey (2014-11-06). "'South Park' is right about why 'The Simpsons' and 'Family Guy' free-to-play games stink". Venture Beat. Retrieved 2014-11-08.

- Rad, Chloi (2015-02-18). "Pokemon Shuffle Is Available Now, Free For 3DS". IGN. Retrieved 2015-04-22.

- Dy, Marijim (2015-04-14). "'Pokémon Rumble World' Recently Released For 3DS; Nintendo's Newest Freemium Game Doesn't Steal Your Money As Much As 'Pokémon Shuffle?'". Youth Health Magazine. Retrieved 2015-04-22.

Further reading

- Anderson, Chris (June 24, 2009). Free: The Future of a Radical Price (1st ed.). Hyperion. ISBN 978-1-4013-2290-8.

- Martins, Rui (January 2016). "Freemium Marketing Strategy – The Good The Bad and The Villain". RuiMartinsBlog.com. Archived from the original on May 13, 2019. Retrieved April 6, 2016.

- Sterling, Bruce (June 2006). "Blogging for Dollars". Wired. Retrieved December 7, 2011.