Occupation of the Rhineland

The Occupation of the Rhineland from 1 December 1918 until 30 June 1930 was a consequence of the collapse of the Imperial German Army in 1918, after which Germany's provisional government was obliged to agree to the terms of the 1918 armistice. This included accepting that the troops of the victorious powers occupied the left bank of the Rhine and four right bank "bridgeheads" with a 30-kilometre (19 mi) radius around Cologne, Koblenz, Mainz and a 10-kilometre (6 mi) radius around Kehl. Furthermore, the left bank of the Rhine and a 50-kilometre-wide (31 mi) strip east of the Rhine was declared a demilitarized zone. The Treaty of Versailles repeated these provisions, but limited the presence of the foreign troops to fifteen years after the signing of the treaty (until 1934).

French soldiers at Ehrenbreitstein Fortress watching over the Deutsches Eck, 1929 | |

| Date | 1 December 1918 – 30 June 1930 |

|---|---|

| Duration | 11 years, 6 months, 4 weeks and 1 day |

| Location | Left Bank of the Rhine, Germany |

| Coordinates | 50°21′26.7″N 7°36′07.0″E |

The purpose of the occupation was on the one hand to give France security against a renewed German attack, and on the other to serve as a guarantee for reparations obligations. After this was apparently achieved with the Young Plan, the occupation of the Rhineland was prematurely ended on 30 June 1930. The administration of occupied Rhineland was under the jurisdiction of the Inter-Allied Rhineland High Commission with its seat at the Upper Presidium of the Rhine Province in Koblenz.

— blue: France, including the former American zone around Koblenz

— yellow: Belgium

— brown: United Kingdom

— stripes : Ruhr, occupied by France and Belgium

— green: Saar, occupied by France under the auspices of the League of Nations[1] French forces continued to occupy German territory in the Rhineland until the end of 1930, while France continued to control the smaller Saarland region until 1935.[2]

Periods

- Armistice of Compiègne (11 November 1918 – 13 December 1918)

- First prolongation of the armistice (13 December 1918 – 16 January 1919)

- Second prolongation of the armistice (16 January 1919 – 16 February 1919)

- Third prolongation of the armistice (16 February 1919 – 10 January 1920)

- 28 June 1919: Signing of the Treaty of Versailles and the Rhineland Agreement

- 10 January 1920: Treaty of Versailles and Rhineland Agreement come into force; Foundation of the Inter-Allied Rhineland High Commission

- 11 January 1923: Occupation of the Ruhr

- 1926: Withdrawal from the Northern Zone around Cologne

- 1929: Withdrawal from the Central Zone around Koblenz

- 1930: Withdrawal from the Southern Zone around Mainz, resulting in the end of the occupation

- 1936: Remilitarization of the Rhineland by German troops under Hitler, on March 7.

Occupying forces

American forces (1918–1923)

The United States occupied the central area of the Rhineland along the Mosel river and the Koblenz bridgehead. General John J. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Forces (A. E. F.), created the Third Army for this purpose, giving the command to Major General Joseph T. Dickman, which, in early 1919, comprised some 250,000 men.[3] The Americans opened their headquarters in a Prussian government building by the Rhine in Koblenz. In those days, the US flag flew over Ehrenbreitstein Fortress.[4]

In July 1919, the Third Army was disbanded and replaced by the American Forces in Germany (AFG) under the command of Major General Henry Tureman Allen. After a constant troop withdrawal, the AFG comprised some 20,000 men in a reduced territory in late 1919.[5] Compared to the French occupation zone, the Americans got along with the German population much better, including a number of love affairs. General Allen even took part in saving Ehrenbreitstein Fortress from destruction by the Allied forces in 1922.[6]

On January 9, 1923, under the Warren G. Harding administration, the U.S. Senate passed a resolution withdrawing the Americans from Germany. General Allen received the telegram on January 10.[7] After more than four years of occupation, the last Americans left their headquarters in Koblenz in January 1923. The flag was lowered at Ehrenbreitstein Fortress, the American headquarters, on January 24.[8] On January 27 American General Allen officially handed over control to the French.[8] On February 3, the United States withdrew General Allen as its observer from the Inter-Allied Rhineland High Commission.[8] Two weeks later the Americans physically left the Rhineland.[8] The American occupation zone was consequently handed over to the French, who from that moment on controlled the major portion of the occupied Rhineland.[9]

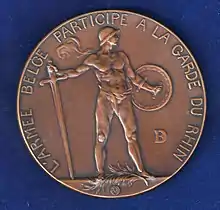

Belgian Army of Occupation

Belgium maintained an army of occupation (Armée d'occupation, AO) in the Rhineland from 1918 to 1929. It consisted of 20,000 soldiers in five divisions[10] with their headquarters at Aachen,[11] and its troops stationed in Krefeld.[12] They were commanded by Armand Huyghé. Belgium also participated in the Occupation of the Ruhr in 1923. 11 Belgian soldiers were killed in an attack on a railway bridge near Hochfeld on 30 June 1923.[13]

The Belgian Army of Occupation maintained a dedicated security service known as the Military Security Service in Occupied Germany (Sûrété militaire en Allemagne occupée, SMAO) which provided some support to Rhenish separatists. After an officer of the SMOA shot dead a German officer of the Schutzpolizei in March 1921, German police mistakenly assassinated another Belgian lieutenant Graff.[13]

British Army of the Rhine

The British Army entered German territory on 3 December 1918.[14] The British Army of the Rhine was established as the occupying force in March 1919. Based at Cologne, they published The Cologne Post.

French Army of the Rhine

The French Eighth and Tenth Armies originally constituted the French forces involved in the occupation. The Eighth Army was commanded by General Augustin Gérard and occupied the Palatinate. The Tenth Army was commanded by General Charles Mangin and was responsible for the rest of the French zone from its headquarters in Mainz.

On 21 October 1919, they were combined to form the French Army of the Rhine.

In 1919, the Italian "Alpi" Brigade was also used by the French in occupation duties in the far south of the zone.[15] France also stationed between 25,000 and 40,000 French colonial soldiers in the Rhineland.[16] Some German women married African soldiers from the occupying forces, while others had children by them out of wedlock (hence the disparaging label "Rhineland Bastards")[17] and were considered by right-wing Germans to constitute a public disgrace.[18] General Henry Tureman Allen reported to US Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby that from the start of the occupation until June 1920 there were 66 cases of formal accusations against colored colonial troops, out of which there were 28 convictions, and admits there were many more unreported cases.[19] Despite these occasional cases, "the wholesale atrocities by French negro Colonial troops alleged in the German press, such as the alleged abductions, followed by rape, mutilation, murder and concealment of the bodies of the victims are false and intended as political propaganda".[20]

French occupation of Frankfurt occurred from 6 April to 17 May 1920. On the second day nine civilians were shot by Moroccan troops in an incident outside the Hauptwache. This incident was used to launch a racist campaign against the French use of colonial troops, linking the incident with allegations of wide spread assaults by Black soldiers in the French occupation army on local women[19] including accusations of systemic rape and other atrocities targeting the German civilian population and attributed mainly to Senegalese Tirailleurs.[21] The events resulted in a widespread campaign by the German right-wing press, which dubbed them as "The Black Shame" (Die schwarze Schande or Die schwarze Schmach) and depicted them as a form of French humiliation of the German nation.[22]

In 1923, in response to German failure to pay reparations under the Treaty of Versailles, France and Belgium occupied the industrial Ruhr area of Germany, most of which lies across the river on the east bank of the Rhine, until 1925. Some Germans and French soldiers were killed or injured during civil disobedience protests. e.g. against dismissal of German officials.[23][24]

Siamese Expeditionary Forces

The Siamese Expeditionary Forces also participated in the occupation until 1919 with their troops being stationed in Neustadt an der Weinstraße, located in the French area.[25]

References

- Edmonds, (1943), p. 1

- Emmanuel Pénicaut (15 March 2009). "L'armée française en Sarre, 1918-1930". Revue Historique des Armées (in French) (254): 20–28., Revue historique des armées, Service historique de la défense.

- Holzheimer (2019), pp. 12-15

- Holzheimer (2019), pp. 62-65

- Holzheimer (2019), pp. 51-54

- Holzheimer (2019), pp. 75-76

- Makowicki & Neumann 2022, p. 79.

- Makowicki & Neumann 2022, pp. 80–81.

- Holzheimer (2019), pp. 181-184

- Pawley (2008) p. 39

- Anne, Godfroid. "Occupation after the War (Belgium and France)". 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- Pawley (2008) p. 41

- "Sûrété militaire en Allemagne occupée (SMAO)". Digithermis. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- Philip Gibbs on the Allied Occupation of the Rhineland, December 1918 accessed 11 September 2010

- Massimiliano Fassero (2015), The II Italian Corps Deployment on the Western Front during the First World War (April 1918–May 1919) (PDF) (Master's thesis), U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, archived (PDF) from the original on 29 March 2022, pp. 62–63.

- Wigger (2010) p. 35

- Tina Campt, Other Germans: Black Germans and the Politics of Race, Gender, and Memory in the Third Reich (University of Michigan Press, 2004), p. 50 ff.

- Julia Roos, "Women's Rights, Nationalist Anxiety, and the 'Moral' Agenda in the Early Weimar Republic: Revisiting the 'Black Horror' Campaign against France's African Occupation Troops". Central European History, 42 (September 2009), 473–508.

- "Finds Negro troops orderly on Rhine" (PDF). The New York Times. 20 February 1921.

Undoubtedly many cases have occurred where many girls or women have been assaulted by of the French colored Colonial troops...cases which were not included in official figures...natural desire to keep out...

- "FINDS NEGRO TROOPS ORDERLY ON RHINE; General Allen Reports Charges Are German Propaganda, 'Especially for America'", The New York Times, 20 February 1921

- LES TIRAILLEURS SENEGALAIS ET L’ANTHROPOLOGIE COLONIALE UN LITIGE FRANCO-ALLEMAND AUX LENDEMAINS DE LA PREMIERE GUERRE MONDIALE Archived 12 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Hans-Jürgen Lüsebrink

- La « Honte Noire ». Racisme et propagande allemande après la Première Guerre mondiale, Estelle Fohr-Prigent

- "Anaconda Standard". 10 February 1923.

Twenty Germans were said to have been killed and several French soldiers wounded when a mob at Rapoch attempted to prevent the expulsion of one hundred officials. Picture shows French guard being doubled outside the station at Bochum following a collision between German mob and the French

- "Hanover Evening Sun". 15 March 1923.

Three Germans killed in Ruhr by French sentries

- Duncan Stearn (22 August 2009). "Thailand and the First World War". First World War.com. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- Makowicki, Shane D.; Neumann, Brian F. (2022). "The US Army Campaigns of World War I: Occupation and Demobilization 1918-1923" (PDF). United States Army. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

Bibliography

- Edmonds, J.E. (1987) [1943]. The Occupation of the Rhineland 1918–29. HMSO. ISBN 978-0-11-290454-0.

- Holzheimer, Marc (2019). The American Occupation of the Rhineland, 1918-1923. ISBN 9781092160933.

- Pawley, Margaret (2008). The Watch on the Rhine: The Military Occupation of the Rhineland, 1918–1930. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-457-2.

- Wigger, Iris (2010). "'Black Shame' – the campaign against 'racial degeneration' and female degradation in interwar Europe". Race and Class. Institute of Race Relations. 51 (3): 33–46. doi:10.1177/0306396809354444. ISBN 978-1-84787-414-6. ISSN 0306-3968. S2CID 144089161.

External links

- The French Occupation of the Rhineland, 1918–1930

- Map of Europe Archived 16 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine during the Occupation of the Rhineland at omniatlas.com