French cruiser Châteaurenault (1898)

Châteaurenault was a large protected cruiser built for the French Navy in the late 1890s and early 1900s. She was intended to serve as a long-range commerce raider, designed according to the theories of the Jeune École, which favored a strategy of attacking Britain's extensive merchant shipping network instead of engaging in an expensive naval arms race with the Royal Navy. As such, Châteaurenault was built with a relatively light armament of just eight medium-caliber guns, but was given a long cruising range and the appearance of a large passenger liner, which would help her to evade detection while raiding merchant shipping.

Châteaurenault coaling in Toulon during World War I | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Operators | |

| Preceded by | Guichen |

| Succeeded by | D'Estrées class |

| History | |

| Name | Châteaurenault |

| Laid down | May 1896 |

| Launched | 12 May 1898 |

| Commissioned | October 1902 |

| Fate | Sunk, 14 December 1917 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Protected cruiser |

| Displacement | 7,898 long tons (8,025 t) |

| Length | 135 m (442 ft 11 in) lwl |

| Beam | 17 m (55 ft 9 in) |

| Draft | 7.39 m (24 ft 3 in) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | |

| Speed | 24 knots (44 km/h; 28 mph) |

| Range | 7,500 nmi (13,900 km; 8,600 mi) at a speed of 12 kn (22 km/h; 14 mph) |

| Crew | 604 |

| Armament | |

| Armor |

|

Châteaurenault spent much of her early career overseas in French Indochina, deploying there immediately after her commissioning in 1902 through mid 1904, and then again in 1905–1906. She was reduced to reserve in 1907 and then modified to serve as a fast minelayer the following year. She was assigned to the Reserve Division of the Mediterranean Squadron. She saw little further activity until the outbreak of World War I in July 1914.

The ship was mobilized into the 2nd Light Squadron and based in the western English Channel. She was moved to the Mediterranean Sea in early 1915 and then to French Senegal to search for German commerce raiders in early 1916. Having been transferred back to the Mediterranean by October 1916, she rescued survivors from the troopship SS Gallia that had been sunk by a German U-boat. Châteaurenault was herself torpedoed and sunk in December 1917, but she sank slowly enough for her crew to be taken off by a pair of destroyers, which in turn sank the German submarine.

Background and design

In the mid-1880s, elements in the French naval command argued over future warship construction; the Jeune École advocated building long-range and fast protected cruisers for use as commerce raiders on foreign stations while a traditionalist faction preferred larger armored cruisers and small fleet scouts, both of which were to operate as part of the main fleet in home waters. By the end of the decade and into the early 1890s, the traditionalists were ascendant, leading to the construction of several armored cruisers of the Amiral Charner class, though the supporters of the Jeune École secured approval for one large cruiser built according to their ideas, which became D'Entrecasteaux.[1]

.jpg.webp)

These debates took place in the context of shifting geopolitical alliances and rivalries. The early 1890s was marked by serious strategic confusion in France; despite the Franco-Russian Alliance of 1891, which should have produced friction between the two countries and their imperial rival Britain, the French Navy was still oriented against the German-led Triple Alliance. This outlook was cemented in the naval program of 1894, but even the Navy's strategic planning remained muddled. The program authorized the large protected cruisers Châteaurenault and Guichen, both of which were intended as long-distance commerce raiders. These vessels were ideally suited to attack the extensive merchant shipping network of Britain, not the continental powers of Germany or Austria-Hungary.[1]

In the early 1890s, the United States Navy built two very large and fast cruisers intended to raid merchant shipping in the Atlantic, the Columbia class. These ships greatly impressed many senior officers in the French Navy, including the French Naval Minister, Félix Faure, who issued requests for design proposals in late 1894. the chief characteristics were very high speed and great cruising range on a displacement of around 8,500 t (8,400 long tons; 9,400 short tons). Because the vessel was not intended to engage enemy cruisers, armament and armor could be kept light for a ship of this size. The Conseil des Travaux (Council of Works) issued its more detailed list of specifications to shipyards on 18 December 1894 to solicit design proposals.[2]

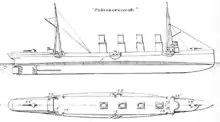

Three shipyards submitted designs by early 1895, and on 15 January, the Conseil evaluated the submissions; they selected two, one from Ateliers et Chantiers de la Loire (which became Guichen) and one from Société Nouvelle des Forges et Chantiers de la Méditerranée (which became Châteaurenault). The latter ship was designed by Antoine Lagane, and the finalized design was approved on 23 July. Lagane intended Châteaurenault to resemble a passenger liner, which would help her evade discovery while conducting commerce raiding operations. To this end, he gave the ship four tall and evenly spaced funnels and an overhanging stern, common features of liners of the day.[3]

The French cruisers suffered from several defects, including insufficient speed to catch the fast transports that would be used to carry critical materiel in wartime and their vast expense militated against their use to attack low-value shipping. Additionally, their weak armament precluded their use against enemy cruisers.[1] And Châteaurenault suffered from severe vibration at high speeds that could not be eliminated despite repeated attempts.[4]

General characteristics and machinery

Châteaurenault was 135 m (442 ft 11 in) long at the waterline, with a beam of 17 m (55 ft 9 in) and a draft of 7.39 m (24 ft 3 in). She displaced 7,898 long tons (8,025 t). Her hull had a long forecastle deck that extended almost her entire length; her stem was slightly sloped backward and she had an overhanging stern. Combined with her four raked and equally spaced funnels, her appearance was adopted to make it relatively easy to disguise her as a passenger liner while on commerce raiding patrols. Her lower hull had straight sides, with a slight tumblehome above the waterline, rather than the pronounced tumblehome shape that characterized most other large French warships of the period.[5][6]

The ship was fitted with a pair of light pole masts for observation and signalling purposes; they were also fitted with platforms for six searchlights. Her superstructure was fairly minimal, consisting of a conning tower and bridge structure forward and a smaller, secondary conning position aft. Her crew numbered 604 officers and enlisted men. French naval officers considered Châteaurenault to have improved handling characteristics over her predecessor Guichen. Most of her auxiliary equipment was electric-powered, apart from her boat hoists, which used steam from her propulsion system. Her electric plan consisted of four dynamos rated at 80 volts.[5][7]

The ship's propulsion system consisted of three vertical triple-expansion steam engines driving three screw propellers. Steam was provided by fourteen coal-burning, Normand Sigaudy water-tube boilers. The boilers were divided into four boiler rooms, three groups of four and a fourth group of two. These were ducted into four funnels located amidships; the funnel number and arrangement was also selected to give her the appearance of a passenger liner. Her machinery was rated to produce 23,000 indicated horsepower (17,000 kW) for a top speed of 24 knots (44 km/h; 28 mph) Coal storage amounted to 1,960 long tons (1,990 t).[5][8] Her cruising range was 7,500 nautical miles (13,900 km; 8,600 mi) at a speed of 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph).[9] During her initial speed test, she only reached 23.12 knots (42.82 km/h; 26.61 mph) from 21,600 ihp (16,100 kW).[10]

Armament and armor

Despite her large size, Châteaurenault carried a relatively light armament, since she was intended to engage unarmed merchant vessels, not other cruisers. Her main battery consisted of two 164 mm (6.5 in) M1893 45-caliber (cal.) quick-firing (QF) gun in single pivot mounts, fore and aft on the centerline, which fired a variety of shells, including solid cast iron projectiles, and explosive armor-piercing (AP) and semi-armor-piercing (SAP) shells. The muzzle velocity ranged from 770 to 880 m/s (2,500 to 2,900 ft/s).[5][11] These were supported by a secondary battery of six 138 mm (5.4 in) M1893 45-cal. QF guns. Two of these were carried in sponsons amidships, while the other four were in casemates on the main deck level, one pair abreast the conning tower and the other abreast the main mast.[5] They were also supplied with cast iron, AP, and SAP projectiles, firing with a muzzle velocity of 730 to 770 m/s (2,400 to 2,500 ft/s).[12] For close-range defense against torpedo boats, she was armed with a battery of ten 47 mm (1.9 in) 3-pounder Hotchkiss guns and five 37 mm (1.5 in) 1-pounder guns.[5] All of the guns were supplied from individual magazines, with electrically or manually-operated shell hoists.[13]

Armor protection consisted of Harvey steel. Châteaurenault had a curved armor deck that was 55 mm (2.2 in) thick on the flat portion, which was about 0.79 m (2 ft 7 in) above the waterline. Toward the sides of the hull, it sloped downward to provide a measure of vertical protection, terminating at the side of the hull about 1.37 m (4 ft 6 in) below the waterline. The sloped portion increased in thickness to 100 mm (4 in), though toward the bow and stern, it was reduced to 40 mm (1.6 in). An anti-splinter deck was above the flat portion of the main deck with a cofferdam connecting it to the main deck. The forward conning tower was protected by 160 mm (6.3 in) on the sides; an armored supporting tube protected by 150 mm (5.9 in) of armor connected it to the interior of the ship. The ship's main guns were each fitted with gun shields that were 55 mm thick.[14]

Service history

Châteaurenault was built at the Société Nouvelle des Forges et Chantiers de la Méditerranée shipyard in La Seyne-sur-Mer, beginning with her keel laying on 23 May 1896. She was launched on 12 May 1898, and was commissioned to begin sea trials on 24 October 1899.[4] which continued through October. These included endurance tests on 8 August, where she cruised at a speed of 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph) for twenty hours. While operating at high speed, the ship's engines suffered from excessive vibration;[15] the brass bearings in her engines were found to be problematic, so they were replaced with steel bearings.[16] The propeller shafts were entirely dismantled and rebuilt to ensure they were aligned properly in another attempt to rectify the vibration problems.[4] The work delayed her completion by several months, and during speed tests in 1902, she reached 24.15 knots (44.73 km/h; 27.79 mph).[16] The ship was finally placed in full commission on 10 October 1902. The vibration problem was never entirely resolved during her lengthy trials, and it was found that she could not steam between 20 and 22.5 knots (37.0 and 41.7 km/h; 23.0 and 25.9 mph), since the engine vibrations matched the resonant frequency of the ship's stern, and the vibration could be dangerous to the ship.[4]

She was activated immediately after being commissioned for service in China to relieve the cruiser D'Entrecasteaux, and she sailed from Toulon on 30 October.[4] As of 1903, the unit also included the armored cruiser Montcalm and the protected cruisers Bugeaud and Pascal.[17] Châteaurenault remained in Asia through mid-1904, along with the armored cruisers Sully, Gueydon, and Montcalm and the protected cruisers Descartes and D'Assas.[18] On 7 November, Châteaurenault struck an uncharted rock off Phan Rang, French Indochina, and had to return to France for repairs. She was unable to depart Indochina until 12 March, when Guichen arrived to replace her. After arriving back in France, Châteaurenault was decommissioned for lengthy repairs, and she remained out of service until 1910.[4] During this period out of service, in 1908, Châteaurenault was selected for conversion into a fast minelayer.[19] The naval command believed her resemblance to a passenger liner would again help her to evade detection while laying minefields.[20] The work was never actually carried out, however.[4]

Châteaurenault was recommissioned on 15 January 1910, and just fifteen days later, she accidentally ran aground off Cape Spartel, Morocco in poor weather. The protected cruiser Du Chayla and two tugboats refloated the ship and towed her to Gibraltar, and the armored cruiser Victor Hugo then towed her from Gibraltar to Toulon.[4] By 1911, Châteaurenault had been assigned to the Reserve Division of the Mediterranean Squadron, based in Toulon. The unit initially also included the armored cruisers Victor Hugo and Jules Michelet and the protected cruiser Jurien de la Gravière, and later that year, it was strengthened with the addition of the armored cruiser Jules Ferry.[21] Châteaurenault thereafter became the flagship of the Training Division of the Atlantic, where she housed a school for boatswains. The ship served in this capacity through 1913.[4]

World War I

At the start of World War I in August 1914, Châteaurenault was assigned to the 2nd Light Squadron, which was based in the English Channel. At that time, the unit consisted of the armored cruisers Marseillaise, Amiral Aube, Jeanne d'Arc, Gloire, Gueydon, and Dupetit-Thouars. The unit was based in Brest, France, and along with Lavoisier, the squadron was strengthened by the addition of several other cruisers over the following days, including the armored cruisers Kléber and Desaix, the protected cruisers Lavoisier, D'Estrées, Friant, and Guichen, and several auxiliary cruisers. The ships then conducted a series of patrols in the English Channel in conjunction with a force of four British cruisers.[22]

In April 1915, she was moved to the Mediterranean as the Allies expanded their naval operations in the area.[23] In February 1916, she was sent to reinforce the 3rd Light Division, which consisted of Gloire, Gueydon, and Dupetit-Thouars. The unit was sent to Dakar in French Senegal to patrol for German commerce raiders operating in the south Atlantic.[24] She joined in the search for the commerce raider SMS Möwe in September.[25] Châteaurenault moved back to the eastern Mediterranean by October. On 4 October, the troopship SS Gallia, a converted passenger liner carrying more than 2,000 soldiers and crew to Greece, was torpedoed and sunk by a German U-boat. No distress signal could be sent before she rapidly sank, leaving thousands in the water; more than 1,300 died before Châteaurenault passed through the area the next day and picked up the survivors.[26] As the threat of U-boats increased in late 1916, against which large cruisers were particularly vulnerable, the French naval command ordered Châteaurenault and the rest of the division to return home.[24]

On 14 December 1917, Châteaurenault was steaming to Salonika carrying a contingent of 985 troops to take part in the Allied intervention in Greece. While passing into the Gulf of Corinth, she encountered the German U-boat UC-38, which hit Châteaurenault with a single torpedo, inflicting fatal damage. Ronald Ross, a Nobel laureate, was aboard Châteaurenault at the time, and he recounted the sinking in his memoirs, noting that the ship sank slowly enough for the crew to be taken off by her escorting destroyers Mameluck and Lansquenet and nearby drifters. The only casualties were a small number of engine-room personnel who were killed by the torpedo explosion itself. UC-38 attempted to maneuver for a second shot while Châteaurenault began to sink, but Mameluck and Lansquenet launched depth charges that forced the U-boat to surface, where she was sunk by gunfire. The German survivors were also picked up by the destroyers, which carried them to Patras, before continuing on to disembark the 1,162 survivors from Châteaurenault at Itea.[25][27][28]

Notes

- Ropp, p. 284.

- Roberts, pp. 233–234.

- Roberts, pp. 234–236.

- Roberts, p. 236.

- Campbell, p. 313.

- Ships, p. 881.

- Ships, pp. 881, 883–884.

- Ships, p. 883.

- Leyland & Brassey, p. 36.

- Leyland 1900, p. 25.

- Friedman, p. 221.

- Friedman, p. 224.

- Ships, p. 882.

- Campbell, pp. 312–313.

- Leyland 1901, pp. 35–36.

- Brassey & Leyland, p. 18.

- Brassey 1903, p. 62.

- Garbett, p. 709.

- Burgoyne, p. 58.

- Clayton, p. 49.

- Brassey 1911, p. 56.

- Meirat, p. 22.

- Jordan & Caresse, p. 225.

- Jordan & Caresse, p. 242.

- Smigielski, p. 194.

- Wise & Baron, p. 90.

- Halpern, p. 399.

- Ross, pp. 520–522.

References

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1903). "Chapter III: Relative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 57–68. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1911). "Chapter III: Comparative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 55–62. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. & Leyland, John (1902). "Chapter II: The Progress of Foreign Navies". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 15–46. OCLC 496786828.

- Burgoyne, Alan H. (ed.). "The Dual Alliance: The French Navy". The Navy League Annual, 1908–1909. London: The Navy League: 51–59. OCLC 861240927.

- Campbell, N. J. M. (1979). "France". In Gardiner, Robert (ed.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 283–333. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5.

- Clayton, Anthony (2016). Three Republics One Navy: A Naval History of France 1870-1999. Solihull: Helion. ISBN 978-1-911096-74-0.

- Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One: Guns, Torpedoes, Mines and ASW Weapons of All Nations; An Illustrated Directory. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- Garbett, H., ed. (June 1904). "Naval Notes: France". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. London: J. J. Keliher & Co. XLVIII (316): 707–711. OCLC 1077860366.

- Halpern, Paul G. (2015). The Naval War in the Mediterranean: 1914–1918. London: Routledge. ISBN 9781317391869.

- Jordan, John & Caresse, Philippe (2019). French Armoured Cruisers 1887–1932. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5267-4118-9.

- Leyland, John (1900). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). "Chapter II: The Progress of Foreign Navies". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 24–62. OCLC 496786828.

- Leyland, John (1901). "Chapter II: The Progress of Foreign Navies". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 33–70. OCLC 496786828.

- Leyland, John & Brassey, Thomas A. (1898). "Chapter II: The Progress of Foreign Navies". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 32–69. OCLC 496786828.

- Meirat, Jean (1975). "Details and Operational History of the Third-Class Cruiser Lavoisier". F. P. D. S. Newsletter. Akron: F. P. D. S. III (3): 20–23. OCLC 41554533.

- Roberts, Stephen (2021). French Warships in the Age of Steam 1859–1914. Barnsley: Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-5267-4533-0.

- Ropp, Theodore (1987). Roberts, Stephen S. (ed.). The Development of a Modern Navy: French Naval Policy, 1871–1904. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-141-6.

- Ross, Ronald (1923). Memoirs: With a Full Account of the Great Malaria Problem and its Solution. John Murray: London. OCLC 35714189.

- "Ships". Journal of the American Society of Naval Engineers. Washington D.C.: R. Beresford. X (3): 798–899. August 1898.

- Smigielski, Adam (1985). "France". In Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. pp. 190–220. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8.

- Wise, James E. & Baron, Scott (2004). Soldiers Lost at Sea: A Chronicle of Troopship Disasters. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 9781591149668.