Fritz Wiessner

Fritz Wiessner (February 26, 1900 – July 3, 1988) was a German American pioneer of free climbing. Born in Dresden, Germany, he immigrated to New York City in 1929 and became a U.S. citizen in 1935. In 1939, he made one of the earliest attempts to conquer K2, one of the most difficult mountains in the world to climb.

Fritz Wiessner | |

|---|---|

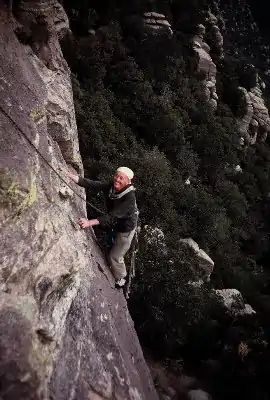

Wiessner, age 86, on the Rupley Towers, Mount Lemmon, Arizona | |

| Born | February 26, 1900 Dresden, Germany |

| Died | July 3, 1988 (aged 88) |

| Citizenship | U.S. (after 1935) |

| Known for | Pioneer of free climbing |

| Spouse | Muriel Schoonmaker |

| Children | 2 |

Early days

Wiessner started climbing with his father in the Austrian Alps before World War I. At the age of 12, he climbed the Zugspitze, the highest peak in Germany. In the 1920s, he established hard climbing routes in Saxony and the Dolomites that have a present-day difficulty rating of up to 5.11. That was at a time when the hardest free climbing grade in the United States was 5.7. At the age of 25, he made a first ascent of the Fleischbank in Tyrol, which was proclaimed the hardest rock climb done at that time.

Wiessner's physical qualities were atypical of mountaineering. He was 5 ft 6 in (168 cm) tall, slope-shouldered and stocky. He had a wide and friendly grin and his speciality was wide crack, or off-width, climbing, a technique that demands both technical mastery and uncommon strength.

A new standard

In 1931, Wiessner made contact with members of the American Alpine Club and immediately set a new standard in American rock climbing. Across North America, he established a substantial list of first ascents at such climbing areas as Ragged Mountain (Connecticut); Cannon Mountain (New Hampshire); Wallface Mountain, New York Adirondack Mountains; Mount Rushmore National Memorial, South Dakota; Devils Tower, Wyoming (the first free ascent); and Mount Waddington, British Columbia.

In 1935, while climbing at Breakneck Ridge on the Hudson River, Wiessner spotted the gleaming white quartzite cliffs of the Shawangunks in the distance. The following weekend he set off in search of the tantalizing cliffs and immediately set about climbing the highest point in the area, a cliff now known as Millbrook mountain. Along with John and Peggy Navas, he established a route now named Old Route 5.5, the first recorded technical rock climb in the Shawangunks, and in doing so helped to establish the area as a mecca for rock climbers.

Wiessner, often in partnership with fellow immigrant Hans Kraus, established numerous first ascents in the Gunks, including many climbs that are popular (and intimidating) to this day. Perhaps their best known combined effort is the very popular High Exposure buttress 5.6, which they first climbed in 1941 with a hemp rope and three soft iron pitons. Other notable Wiessner first ascents in the Gunks include: Gargoyle 5.5, High Traverse 5.5, White Pillar 5.7, Baby 5.6, Frogs Head 5.6; Gelsa 5.4, High Corner 5.7 and Yellow Ridge 5.7. In 1946, he led Minnie Belle, the first 5.8 in the Gunks.

In 1935, Wiessner established a climb in Connecticut called Vector. 5.8.

When rock climbing, Wiessner often paired himself with novices, and with women in particular. He always insisted on being the lead climber (in an era when a leader fall could easily prove disastrous for the entire party and the maxim of the day was "The leader must never fall"). After meeting Hans Kraus, he relaxed his "lead-climb only" rule (which Kraus had also adopted), and the two men climbed as equal partners.

K2 expedition

In 1939, he led an ill-fated American expedition to K2, coming within 700 feet of the summit before having to turn back. Wiessner recounted that, although the difficulties of the climb had been passed and the remainder was straightforward, he turned back in deference to the wishes of his sherpa, Pasang Dawa Lama. The expedition was tainted by the loss of Dudley Wolfe, and initial accounts of the climb lay much of the blame on expedition leader Wiessner. In a 1956 article Wiessner instead directed criticism towards Jack Durrance. The controversy would be reignited after Durrance was convinced to release his personal expedition diary in 1989, which laid blame on the failings of both the deputy party leader Tony Cromwell and Wiessner.

No one came as close to the top of the mountain again until July 31, 1954, when the first ascent was achieved by Lino Lacedelli and Achille Compagnoni on the 1954 Italian Karakoram expedition.

Non-climbing

During his first years in America, Wiessner founded a chemical company that specialized in waxes, including a widely used ski wax known as Wiesner's Wonder Wax. He successfully developed his company during the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Wiessner was also a proficient skier. He was reportedly disappointed that he was not allowed to fight for the U.S. in World War II, serving instead as a technical advisor to the 10th Mountain Division, and to the "equipment for cold climatic areas commission" of the office of the Quartermaster General of the United States Army in Washington, DC.

Later years

Wiessner remained an active climber up into his eighties, often stunning onlookers in the Shawangunks by soloing his early routes. He loved to solo his climb Gargoyle at Skytop by the light of the full moon.

Once, when climbing with a much younger climber sometime in the mid-1970s, the younger climber led the first pitch, and confided to Wiessner that he had soloed the route earlier in the week. "Ah, you must vee climbing pretty goot!" Wiessner said. He then took the lead for the second pitch, putting in no protection—effectively soloing the pitch. When his partner reached the top, Fritz grinned impishly. "I must vee climbing pretty good too" Wiessner (then in his middle 70s) said. (The source for this anecdote is Guy Waterman).

Personal

In 1945, he married Muriel Schoonmaker.[1] In 1946, their son Andrew was born. In 1947, their daughter Pauline (Polly) was born. Daughter and son both accompanied their father on many later expeditions and climbing trips. Muriel was a trusted climbing, scrambling, and skiing companion to Fritz for the rest of his life.

In 1952, the Wiessner family moved to Stowe, Vermont, where Fritz would live to the end of his days. Wiessner died after suffering a series of strokes at age 88.[2][3]

References

- Club, American Alpine (31 October 1997). The American Alpine Journal, 1989. The Mountaineers Books. ISBN 9780930410391.

- Morrill, Greg. "Fritz Wiessner links Stowe and Grand Teton". Vermont Community Newspaper Group.

- "Fritz Wiessner, 88; Career as a Climber Spanned 8 Decades". The New York Times. 6 July 1988.

- Andreas, Gottfried (2000). Fritz Wiessner : 1900 – 1988. Dresden: Sächsischer Bergsteigerbund.

- Curran, Jim (1999). K2: The Story of the Savage Mountain. Seattle, WA: The Mountaineers Books.

- Kauffman, Andrew; Putnam, William (September 30, 1993). K2: the 1939 Tragedy. Mountaineers Books. ISBN 978-0898863734.

- Schwartz, Susan (2005). Into The Unknown: The Remarkable Life of Hans Kraus. Bloomington, Indiana: iUniverse.

- Waterman, Laura and Guy (2000). “The Big Little Man from Dresden,” in Laura and Guy Waterman, A Fine Kind of Madness: Mountain Adventures Tall and True, Seattle, WA: The Mountaineers Books, 2000.

- Waterman, Laura and Guy (1993). Yankee Rock and Ice: A History of Climbing in the Northeastern United States, with A. Peter Lewis, photography. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books.

- Wiessner, Fritz (1955). K2: Tragödien und Sieg am Zweithöchsten Berg der Erde. Munich: Bergverlag Rudolf Rother.

- Williams, Richard (2000). Shawangunk Rock Climbs: The Trapps. Golden, CO: American Alpine Club.

- de:Fritz Wiessner German Wikipedia article

- Partial lists of climbs

- Misc