Gaṇeśa Daivajna

Gaṇeśa Daivajna (born 1507, fl. 1520-1554) was a sixteenth century astronomer, astrologer, and mathematician from western India who wrote books on methods to predict eclipses, planetary conjunctions, positions, and make calculations for calendars. His most major work was the Grahalaghava which was included ephemeris and calendar calculations.

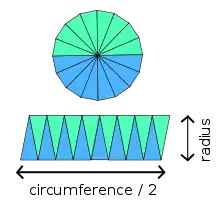

Ganesa was born in Nandigrama (see also Golagrama) where his father Kesava (fl. 1496-1507) was a Brahmin astronomer. His mother's name has been noted as Lakshmi and he spent his entire life at Nandigrama. The location of Nandigrama has been suggested by some as being in Gujarat but more careful study of his work places it in Nandgaon in present day Maharashtra.[1] He wrote several works including Grahalaghava, Siddhantarahasya, Buddhivilāsinī, and Laghutithicintamani.[2] His work Buddhivilāsinī (c. 1546[3]) includes commentaries on the mathematics of Bhaskara's Lilavati.[4] One of his demonstrations is of the area of a circle calculated by dissection of the circle into a regular polygon. He started with a polygon with 12 sides and doubled it through 24, 48, 96, 192, to 384 and came up with an approximation for pi as 3927/1250.[5] His book Muhūrtadipikā includes a commentary on his father Kesava's work Muhūrtatattva. Ganesa's grandfather Kamalakara was also an astrologer as were his brothers Ananta and Rama. Works by Kesava include Grahakautuka (1496) on the calculation of eclipses, Jatakapaddhati for the production of horoscopes, and the Tajikapaddhati, which covered Islamic thoughts on astrology.[6]

References

- Sarma, S.R. (2010). "Nandigrama of Ganesa Daivajna". Indian Journal of History of Science. 45 (4): 569–574.

- Plofker, Kim (2014). "Ganesa". In Hockey, Thomas; Trimble, Virginia; Williams, Thomas R.; Bracher, Katherine; Jarrell, Richard A.; Marché, Jordan D.; Palmeri, JoAnn; Green, Daniel W. E. (eds.). Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer. pp. 781–782. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-9917-7. ISBN 978-1-4419-9916-0. S2CID 242158697.

- Colebrooke, H.T. (1873). Miscellaneous Essays. Volume III. London: Trubner and Co. p. 406.

- Ramasubramanian, K.; Hayashi, Takao; Montelle, Clemency; Ramakalyani, K. (2019), Ramasubramanian, K.; Hayashi, Takao; Montelle, Clemency (eds.), "Gaṇeśa Daivajña's upapattis for some rules in the Līlāvatī", Bhāskara-prabhā, Singapore: Springer Singapore, pp. 102–114, doi:10.1007/978-981-13-6034-3_5, ISBN 978-981-13-6033-6, S2CID 146066627, retrieved 2022-10-14

- Joseph, George Gheverghese (2016). Indian Mathematics: Engaging With The World From Ancient To Modern Times. World Scientific. p. 295.

- Pingree, David (1973). "Kesava". In Gillispie, C.C. (ed.). Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Volume 7. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. pp. 314–316.