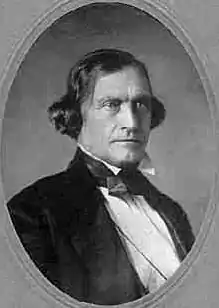

Gabriel Renville

Gabriel Renville (April 1825 – August 26, 1892), also known as Ti'wakan (Sacred Lodge), was Chief of the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate Sioux Tribe from 1866 until his death in 1892. He opposed conflict with the United States during the Dakota War of 1862 and was a driving force within the Dakota Peace Party. Gabrielle Renville's influence and political leadership were critical to the eventual creation of the Lake Traverse Indian Reservation, which lies mainly in present-day South Dakota.

Gabriel Renville | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | April 1825 Sweet Corn Village, Lake Traverse, South Dakota |

| Died | August 26, 1892 Browns Valley, Traverse County, Minnesota |

| Nationality | Dakota Sioux, French Canadian and British descent |

| Citizenship | American |

Early life and family

Gabriel Renville was born in April 1825 to two "mixed-blood" parents –– Winona Abigail Crawford (1805–1897) and Victor Renville (Ohiya) (1780–1832) –– most likely in the village of Sweet Corn on the west shore of Lake Traverse.

His father Victor was the son of Joseph Rainville, a French Canadian fur trader, and Miniyuhe, a Mdewakanton kinswoman of the Little Crow family, and was the younger brother of Joseph Renville of Lac qui Parle (1779–1846). His mother Winona was the daughter of a British trader and a Sisseton woman, and had been previously married to the son of a fur trader, Narcisse Frenier.[1][2]

Victor Renville was ambushed and killed by a group of Ojibwes in August 1832 as he returned from leading a group of soldiers on a retaliatory raid.[3]

A few years after his death, Winona Crawford married Akipa, later known as Joseph Akipa Renville (c. 1810–1891), a "full-blood" Dakota from the Wahpeton band.[1] (Akipa, son of Buffalo Man, was "neither a Renville nor a Mdewakanton"[4] but admired Gabriel's famous uncle and adopted his English name in tribute.)

In 1838, Gabriel Renville settled on Grey Cloud Island in Washington County, Minnesota with his brother-in-law and legal guardian, Joseph R. Brown; his half-sister, Susan Frenier Brown; and his stepfather, Akipa.[5]

Education

Gabriel Renville received little formal education beyond classes at the school at Lac qui Parle Mission, where he learned to read and write the Dakota language, and do arithmetic.[1][3]

When Gabriel was a teenager, Joseph R. Brown placed him in boarding school in Chicago, where he lasted for one month. Gabriel's nephew, frontiersman Samuel J. Brown, later wrote that "schoolroom confinement and association with strangers speaking an unintelligible and strange tongue did not agree with him or suit him, and in about a month he ran away on foot across the prairies of Illinois and the woods of Wisconsin back to his home in Minnesota. He could never be induced to return, but in later years always upbraided my father for not giving him a sound thrashing and sending him back."[1]

Although he avoided speaking English, Gabriel Renville became known as a skilled orator in Dakota. Sam Brown, who served as his interpreter during multiple trips to Washington, D.C., wrote that in his opinion, "Gabriel Renville had no superior –– no equal, even –– as to the use of the Sioux language. He knew the use of it so well and so completely that every word was a sledgehammer, always clear, homely but strong, and to the point."[1]

Decline of the fur trade

In 1841, Joseph R. Brown brought Gabriel Renville in to serve as a clerk in his fur trading business based in the Coteau des Prairies. After Brown sold his business to Henry Hastings Sibley in 1846, Renville worked briefly for Sibley's business partner Martin McLeod. By 1849, Renville had moved back to Lac qui Parle.[3]

The collapse of the fur trade wrought economic hardship in the newly formed Minnesota Territory. In 1850, Brown summoned Renville to Saint Paul, where he was meeting with a group of traders including Sibley to help to facilitate the signing of a treaty between the U.S. government and Dakota leaders, which would also pay traders for any outstanding debts owed to them. Historian Gary Clayton Anderson writes, "Renville quickly became part of the inner circle that worked for the treaty...Given the circumstances, Renville, in working with Brown, obviously assumed that he was helping his people out of what had become an increasingly unsustainable lifestyle."[3]

In 1851, Gabriel Renville was present at the signing of the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux as part of the delegation of Wahpetons. Anderson writes, "When Renville, as a mixed-blood, did not sign, his stepfather, Akipa, gave his mark."[3]

Entry into farming

As news of the 1851 treaty spread, there was a large influx of white settler-colonists attempting to claim indigenous lands in Minnesota Territory, including 320,000 acres of land that had been set aside for "mixed-blood" descendants of European American fur trappers and settlers and certain Dakota tribes in the Fourth Treaty of Prairie du Chien.[6]

To compensate for their loss, the U.S. government authorized a swap, offering "land scrip" to eligible mixed-race applicants in exchange for giving up their claim to the "half-breed tracts."[6]

Gabriel Renville filed for land scrip in 1856, claiming lands south of Fort Ridgely. By 1857, Renville and his cousins had moved north to an area east of the Minnesota River above the Upper Sioux Agency, also known as the Yellow Medicine Agency, close to their old home in Lac qui Parle.[3]

There, Gabriel Renville focused on building a large farm of 3,000 acres[7] in an effort to become self-sufficient and support his growing family. His house was modern, featuring "the first brick fireplace in the region, a progressive symbol for that time."[3]

Although he joined the Presbyterian Church in 1856 and was appointed as a cabinet member of Stephen Return Riggs's "Hazelwood Republic," in practice he refused to abandon many traditional Dakota practices including polygamy. Over the years, Gabriel Renville married three Sisseton Dakota sisters from Scarlet Plume's band, and had at least ten children.[3]

Role in the U.S.-Dakota War

During the Dakota War of 1862, Gabrielle Renville helped to organize the "friendly" soldiers' lodge which opposed the soldiers attacking European American settlements. He was a driving force within the Dakota Peace Party that emerged among the Sisseton and Wahpeton bands, which soon attracted the support of disgruntled Mdewakantons.[8] The peace party sought to end the war and secure the release of prisoners captured by the Dakota soldiers, and made it difficult for the soldiers to sustain the war effort.[9]

.jpg.webp)

Evacuation and stand at Yellow Medicine Agency

On the morning of August 19, 1862, having heard about the attacks on Redwood Agency the night before from Solomon Two Stars, Renville rode out toward the Yellow Medicine Agency to check on his relatives. On the way, he encountered Rev. Thomas Smith Williamson, who was initially unconvinced that he was in danger, and persuaded him to flee. Renville went home to find the horses already hitched to the wagon, and headed towards the agency with his family. They later saw Williamson's family crossing the river to flee eastward with a Native American who was sympathetic to the European Americans of the region and had already helped Riggs's family to safety. Four miles on, Renville was accosted by drunken soldiers who had pillaged the agency, but forced his way through.[8]

At his mother's house, he found that his brother Charles Crawford had managed to return after encountering "hostiles" who wanted to kill him. Later that evening, they received word that their sister Susan Frenier Brown, wife of Joseph R. Brown, had not been killed as they had feared but had been taken prisoner along with her children and son-in-law.[8]

On the morning of August 20, Renville and 12 other Dakota and "mixed-blood" men went to Yellow Medicine Agency to "make a stand" in the agency's brick buildings. Gabriel's stepfather Akipa and his half-brother Charles Crawford then went south to rescue Susan and her children; on August 23, they arrived at Little Crow's camp, where Akipa successfully negotiated their release.[8]

In the days that followed, Renville received word that the hostile soldiers and their families were moving north toward the Yellow Medicine Agency. When Little Crow arrived, he advised Renville, his men and their families to leave the agency buildings since the soldiers would burn them down.[8]

Dakota Peace Party and soldiers' lodge

As Renville, his men and their families moved north, they passed through the hostile soldiers' camp, realizing that over half of the 200 European American and "mixed-blood" prisoners there were women and children.[8]

With tensions running high, Gabriel Renville had the idea to call a council and invite the opposing soldiers to negotiate the release of the prisoners. He killed a calf supplied by his cousin John Baptiste Renville and organized a feast. More than 100 hostile Mdewakanton soldiers arrived with guns, but when Renville invited them to sit down and eat, they could not refuse, according to Dakota tradition.[3] Talks broke down with the soldiers unwilling to release women and children, and the others unwilling to join them.

Renville's side decided to form a single camp of families sympathetic toward the European settler-colonists, with a large tent at the center of a circle west of Riggs's Hazelwood Mission buildings. They organized their own soldiers' lodge, with Renville among the four officers, and Paul Mazakutamani as their spokesman.[8]

The hostile Mdewakantons then called a large council, inviting the "friendlies". Nearly a thousand people total were in attendance. Again, passionate speeches were made on both sides. During the council the Mdewakantons also shared information about the Battle of Birch Coulee, and several hostile soldiers mentioned that they had recognized the voice of Major Joseph R. Brown. Wanting to find out whether Brown was still alive, Renville suggested sending Charles Crawford out to Birch Coulee to investigate how many had been killed.[8]

Upon his return, Crawford reported to Renville that he had found a letter from Colonel Henry Hastings Sibley left on the battleground, inviting the Native Americans to come speak with him without reprisal. Although the "hostiles" were initially opposed and threatened to kill anyone contacting Sibley, Little Crow himself finally agreed that they should send two representatives. When they returned, they reported that Sibley said he would not treat "friendlies" as enemies, and that he would only meet with the opposing soldiers if they released the prisoners first.[8]

Both the "friendlies" and "hostiles" subsequently moved their camps further apart. The "hostiles" moved north but were halted at Red Iron's village; their camp was forced to scatter once shots were fired, breaking up their soldiers' lodge and weakening their position. Meanwhile, the "friendly" camp grew stronger as Mdewakantons weary of conflict, some of whom had reached out secretly to Sibley, joined them. Renville recounted that a group of hostile Mdewakantons then came to attack the peace party, who were ready with guns, but Iron Walker (Mazomani) convinced the hostiles to stand down.[8]

Battle of Wood Lake and Camp Release

On the night of September 22, Little Crow and the soldiers prepared to attack Sibley's troops under cover of darkness and threatened to kill any men who refused to follow. Renville, Two Stars and others argued that Little Crow's battle plan was foolhardy given the numbers of men they had seen in Sibley's command, deliberately prolonging the debate until daylight when the "friendlies" could warn the troops.[8]

On September 23, 1862, when the "hostiles" finally left to attack Sibley's camp, Renville and other members of the friendly camp gathered in a ravine to stay out of the battle.[3] Renville's followers invaded the opposing camp to rescue the white and "mixed-blood" captives and brought them to safety in their camp, while Renville, Solomon Tukanshaciye and others pursued a war party passing westward and compelled them to release additional prisoners.[8] The soldiers led by Little Crow were defeated by Sibley's army at the Battle of Wood Lake.

Sibley and his troops arrived at the "friendly" camp on September 26, 1862. Renville recalled, "With joyous handshaking we met, and the white prisoners were taken into the soldiers' camp."[8]

The Dakota Peace Party handed over a total of 269 prisoners –– 107 white and 162 "mixed-bloods" –– to Sibley at the location which came to be known as Camp Release. Within days, the number increased to 285.[10]

Fort Snelling

.jpg.webp)

On September 28, 1862, a commission appointed by Colonel Sibley began interrogating Dakota men to determine their involvement in the war.[10]

In his memoir, Gabriel Renville wrote, "Then word came that the Indians would be sifted as you would sift wheat, the good grain to be put into the bin, but the chaff and the bad seeds to be burned. This was done, and all those who by good evidence were proven to have done anything against the whites were put into irons."[8]

Renville and Akipa and their families were acknowledged as friendlies and were initially allowed to move freely outside the Native American camp. Renville went home to discover that everything he owned had been taken or destroyed by opposing soldiers. He moved his camp to Redwood Agency with other "friendlies" camped on the north side of Sibley's command. Those who were suspected of having acted against the white settler-colonists were camped on the south side of the troops.[8]

In the weeks before the mass execution, the convicted men were taken to Mankato, whereas their families together with the "friendlies" were taken to Fort Snelling. The Renvilles, Browns and other "friendly" families joined approximately 1,600 Native Americans sent to a compound below Fort Snelling.[3] On their way there, the residents of Henderson threw stones in anger at the Native Americans passing through; among the general white population of Minnesota at the time, all Dakota were blamed for the deaths and destruction that occurred in August 1862. Once they arrived, many of their horses and oxen were stolen from their camps.

Renville recalled, "Then a fence was built on the south side of the fort and close to it. We all moved into this inclosure, but were so crowded and confined that an epidemic broke out among us and children were dying day and night, among them being Two Stars' oldest child, a little girl."[8]

John Williamson, son of Thomas Smith Williamson, received permission to enter the compound housing the Dakota and found many members of the former mission community there, including Gabriel Renville, who lay sick in his tent with a serious case of malaria.[3] Between 130 and 300 people died of various illnesses inside the camp.[9]

Designation as Chief

Thanks to his service during the war, Renvile obtained in 1863 the post of Chief of Scouts in the service of Minnesota state militia Colonel Henry Hastings Sibley—later to become the first governor of the state of Minnesota. His service to the U.S. Army ended in 1865.

For his military service, he was appointed by Sibley as Chief of the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate in 1866. His people seconded Sibley's appointment a year later by declaring Renville chief-for-life. His tenure as chief saw the creation and settlement of his people on the Lake Traverse Reservation. He is buried atop a bluff near Old Agency, South Dakota.

References

- Brown, Samuel J. (April 17, 1914). "Biographical Sketch of Chief Gabriel Renville". The Sisseton Weekly Standard. Retrieved 2021-05-05.

- LaFontaine, Harlen (September 6, 2017). "Renville, Gabriel (1825–1892)". MNopedia. Retrieved 2021-05-06.

- Anderson, Gary Clayton (2018). Gabriel Renville: From the Dakota War to the Creation of the Sisseton-Wahpeton Reservation, 1825-1892. Pierre: South Dakota Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-1-941813-06-5.

- Anderson, Gary Clayton (1986). Little Crow: Spokesman for the Sioux. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society. ISBN 0-87351-196-4.

- Goodman, Nancy and Robert. "Brown, Joseph Renshaw (1805–1870)". MNopedia. Retrieved 2021-05-05.

- Johnson, Frederick L. ""Half-Breed" Tract". MNopedia. Retrieved 2021-05-06.

- "A Famous Indian Chief". The Irish Standard (Minneapolis, Minnesota). September 3, 1892.

- Anderson, Gary Clayton; Woolworth, Alan R., eds. (1988). Through Dakota Eyes: Narrative Accounts of the Minnesota Indian War. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-0-87351-216-9.

- "The Dakota Peace Party". The U.S.-Dakota War of 1862. 3 September 2012. Retrieved 2021-05-07.

- "Camp Release". The U.S.-Dakota War of 1862. 23 August 2012. Retrieved 2021-05-08.

Further reading

- Gary Clayton Anderson, Gabriel Renville: From the Dakota War to the Creation of the Sisseton-Wahpeton Reservation, 1825-1892 (Pierre: South Dakota Historical Society Press, 2018). ISBN 978-1-941813-06-5

- Gary Clayton Anderson and Alan R. Woolworth, ed., Through Dakota Eyes: Narrative Accounts of the Minnesota Indian War of 1862 (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 1988). ISBN 978-0-87351-216-9