Gamlingay

Gamlingay is a village and civil parish in the South Cambridgeshire district of Cambridgeshire, England about 14 miles (23 km) west southwest of the county town of Cambridge.

| Gamlingay | |

|---|---|

Village centre: St Mary's Church and the pub | |

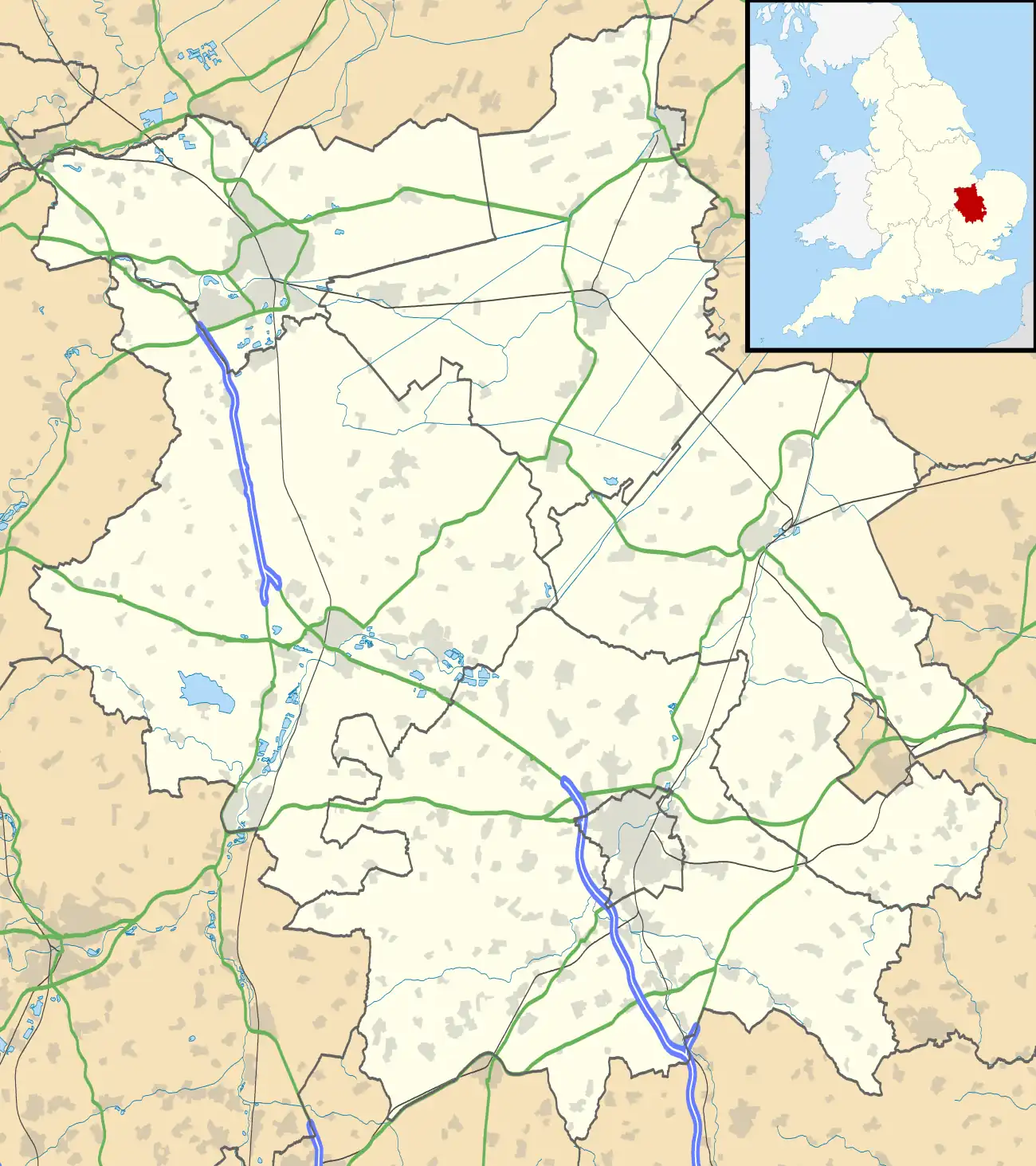

Gamlingay Location within Cambridgeshire | |

| Population | 3,247 |

| OS grid reference | TL236526 |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | SANDY |

| Postcode district | SG19 |

| Dialling code | 01767 |

| Police | Cambridgeshire |

| Fire | Cambridgeshire |

| Ambulance | East of England |

| UK Parliament | |

The 2011 census gives the village's population as 3,247 and the civil parish's as 3,568.[1][2]

In addition to Gamlingay village, the parish includes the outlying areas of Gamlingay Cinques, Gamlingay Great Heath and Little Heath.

History

An ancient village listed in the Domesday Book of 1086, the name comes from the Old English Gamelingei, meaning "the enclosure of Gamela's people".[3]

There has been a settlement on the site since the middle Bronze Age and there are signs of occupation from the middle Stone Age. The village may have first been established around a central green south of the High Street (now known as Church Street); a complex of medieval buildings stood at the east end of the green, but only a tithe barn and the house known as 'Emplins' remain today. Another focal point was provided by the crossroads at the other end of Church Street and houses spread to the south and east of the junction. In the 16th and 17th centuries, Gamlingay grew to the east towards Dutter End and west to Green End. By 1801, Gamlingay had a population twice as large as that of the hundred's second-largest parish, Bourn.[4]

Gamlingay is steeped in history, with many listed buildings in the village. The stone for building the church was from a quarry within the village. This quarry then offered the perfect location for an archery range. Being dug into the ground it was a safe area where archery could be practised, and thus was named 'The Butts'. In medieval times it was a requirement that all men over a certain age were capable of using a bow and arrow. The Butts is now a children's play area.

Throughout history, Gamlingay has been a farming village. Most of the village was owned by the Oxford college Merton, and the Cambridge colleges Downing and Clare. Until a few years ago, the houses (subdivisions) at the local village college were named after Merton, Downing and Clare. Downing College acquired the land as a result of a bequest in the will of Sir George Downing, who lived in a mansion, Gamlingay Park, on his Gamlingay estate.

In 1600, 64 houses – comprising much of the village[4] – were destroyed in the "Great Fire of Gamlingay", as described in an extract of a letter from the Privy Council to Sir Thomas Egerton:

"Whereas divers of the Justices of the Peace in the countie of Cambridge have certyfied us the lamentable accydent that hath fallen upon the inhabitantes of Gamlingay in the said countie, by casualltie of fire that happned on the 21St daie of Aprill last, whereby the moste parte of the said towne to the nomber of 76 houses with divers barnes and stackes of corne were suddainlie consumed."

By 1844, Gamlingay had five inns, including the Cock (dating from at least 1588), the Rose & Crown (1622) and the Blue Ball (1770s). The Sultan was built near the station in 1867.[4] At one time, there were 54 pubs in Gamlingay to serve the coach routes from London. It is claimed that the highwayman Dick Turpin rode through the village on his way north.

Gamlingay had a station on the Bedford and Cambridge branch of the London and North Western Railway,[5] which opened in 1862 and shut in 1968 in the Beeching cuts.[6]

Governance

There are 15 councillors on Gamlingay Parish Council.[7] The parish is represented on South Cambridgeshire District Council by one councillor for the Gamlingay ward[8] and on Cambridgeshire County Council by one councillor for the Gamlingay electoral division.[9] It is in the parliamentary constituency of South Cambridgeshire, represented at the House of Commons by Anthony Browne.[10]

Geography

Gamlingay is 14 miles (22 km) west of the county town of Cambridge, five miles (9 km) south-east of St Neots and 45 miles (72 km) north of London. It is north of the small town of Potton and south-west of Waresley. The parish ranges from 39 metres (along the Millbridge Brook) to 73 metres (near Potton Wood) above sea level.[11] The village is at around 50 metres.[4] Most of the central parish is on the Lower Greensand; the soil in the eastern part of the parish[4] is clay with gault subsoil.[5] Two nature reserves, Gamlingay Wood and Gamlingay Cinques Common (registered Town and Village Green No. 39) can be found in the parish,[12] the former and the latter being a Site of Special Scientific Interest and a County Wildlife Site respectively.

By the 12th century, heathland had developed on the Lower Greensand and the poor drainage of the soil there meant there were two quaking bogs, on Gamlingay Heath (drained in 1855) and Cinques Common. Treeplanting and pig rearing after inclosure in 1844 altered the landscape.[4]

Woodbury used to be in the parish but was transferred to Bedfordshire in 1965 and a hamlet named Newton on the Heath had disappeared by 1279.[4]

Demography

At the time of the 2001 census, Gamlingay parish had 3,535 inhabitants living in 1,410 households. The ethnic group of 99% was white, with 0.4% Asian or Asian British, 0.1% black or Black British, 0.3% mixed and 0.2% other. 77% were Christian, 0.3% followed another religion and 22% cited 'no religion' or did not state one.[13]

Economy

Gamlingay is now largely a commuter village: 44% of its employed residents work outside of Cambridgeshire, 30% more than 20 km away and 11% more than 40 km away.

Farming, mainly arable, was the primary employer in Gamlingay for many centuries. A third of the parish was cultivated in 1801, with wheat the main crop, then barley and peas. In 1937, there were 12 smallholders and 11 market gardeners. There was some gravel extraction south of the village in the late 19th century; in 1864 the village had three brickworks. In 1912, one occupied an area of 31 acres (12.5 hectares), with 12 kilns and a warehouse capable of holding 500,000 bricks. The closure of the brick and tile works probably caused the parish's population to fall in the aftermath of its sale in 1920.[4]

Landmarks

A war memorial, built from Cornish granite, now stands within the new cemetery having been resited from its former position outside Gamlingay Village College and commemorates men from the village who died in the First and Second World Wars.[14]

Two timber-framed buildings in the village date from the late 15th or early 16th centuries: Emplins,[15] a large house near the church, and Merton Manor Farm.[4] A total of 60 buildings in Gamlingay parish are listed, including the Baptist chapel on Stocks Lane,[16] Merton Grange,[17] the Cock Inn,[18] a red telephone box outside the church,[19] and many buildings along Church Street, and 10 north lane

Transport

The B1040 road runs through Gamlingay from Potton to the A14 near Hilton; minor roads lead to Hatley, Everton and Little Gransden.[11] The nearest railway station is at Sandy, Bedfordshire. Buses run from Gamlingay to destinations including Cambridge, St Neots, Great Gransden, Little Paxton and Sandy.[20]

Education

Until 2017, Gamlingay children were educated under the neighbouring Bedfordshire three-tier system but the village aligned with the nationally recognised two-tier system from September 2017. Gamlingay children aged 4–11 years are now educated at Gamlingay Village Primary, part of the Cam Academy Trust. [21] (As Gamlingay Village College it was previously a Middle school and admitted pupils aged from 9–13).[22][23][24] Secondary education follows at Comberton Village College (also a Cam Academy Trust school), Ofsted rated Outstanding, with free school bus provided for 11 - 16 year olds. The nearest secondary schools are Sandy Secondary School and Stratton Upper School, Biggleswade.[25]

Religious sites

Gamlingay parish church the Church of St Mary is dedicated to St Mary the Virgin. It was built around the 12th century in the Early English style with a square tower (now containing eight bells) from field stones and local ironstone. A church existed in the parish before 1120.[4] Gamlingay is part of the ecclesiastical parish of Gamlingay with Hatley St George and East Hatley.

The village's first Baptist church was formed in 1670. Its first recorded minister was John Bunyan, the author of The Pilgrim's Progress. In the beginning the church, which was originally known as Gamlingay Old Meeting, was a daughter congregation of Bunyan Meeting at Bedford, becoming independent in 1710. The meeting house was also built in 1710. It was rebuilt in 1840 and restored in 1881. The church was renamed Gamlingay Baptist Church in the 1990s and they continue to meet at 10.45 every Sunday.[26]

There was also an Anglican mission church at Gamlingay Heath dedicated to St Sylvester, originally constructed in iron in 1879, which closed in the 1980s.

A congregation of Particular Baptists worshipped at a chapel known as Zoar, built around 1800 at Gamlingay Cinques; it was demolished in the mid-1960s. A Primitive Methodist chapel was built at Green End in 1855.[4]

Community amenities

Local amenities include a gym, two pubs, shops, two hairdressers, sports fields, a community centre, clubs and societies, cinema, nursery schools and a Grade II listed telephone box.[19]

Gamlingay is also home to Gamlingay Eco Hub[27] and has its own community music charity, Gamlingay Records.[28]

Notable people

- Sir George Downing, 1st Baronet (1623–1684), politician and builder of Downing Street

- Sir George Downing, 3rd Baronet (1685–1749), politician and founder of Downing College

- Jeremy Irvine Actor, raised in Gamlingay

- Dick Turpin Infamous Highwayman, supposedly rode through Gamlingay while escaping the law

See also

References

- UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – Gamlingay Built-up area (E34003337)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – Gamlingay Parish (E04001787)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- Mills, A.D. (1998). A Dictionary of English Place-names. Second Edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford. p147. ISBN 0-19-280074-4

- Parishes: Gamlingay', A History of the County of Cambridge and the Isle of Ely: Volume 5 (1973), pp. 68–87. Date accessed: 2 August 2008

- GENUKI: Gamlingay

- Subterranea Britannica: Gamlingay Station

- Gamlingay Parish Council: Parish Councillors' Details Archived 7 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 25 July 2009

- South Cambridgeshire District Council: Electoral wards Archived 24 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Cambridgeshire County Council: Councillors Archived 13 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Anthony Browne (politician)

- Ordnance Survey: www.getamap.co.uk

- "A to Z list of Wildlife Trust nature reserves". The Wildlife Trusts. Archived from the original on 9 February 2014. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- Cambridgeshire County Council: Parish Census profile 2001 Archived 14 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Roll of Honour: Gamlingay

- Historic England. "The Emplins (1309190)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- Historic England. "Baptist Chapel, Stocks Lane (1128151)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- Historic England. "Merton Grange, Station Road (1128150)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- Historic England. "Cock Inn (1330904)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- Historic England. "Telephone Kiosk, Church Street (1330923)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- Travel Search: Gamlingay

- Gamlingay Village Primary

- Gamlingay Village College

- "Bassingbourn Village College: Gamlingay". Archived from the original on 4 October 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2008.

- Cambridgeshire County Council: Gamlingay Library Access Point Archived 21 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Hatley.info: Schools

- "GamlingayBaptistChurch". Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- "Gamlingay Eco Hub". Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- "Gamlingay Records". Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

Further reading

- James Brown, Gamlingay: Six Hundred Years of Life in an English Village (London: Cassell, 1989)

- James Brown, Villagers: 750 Years of Life in an English Village (Amberley Publishing, 2011)

External links

- Book : Villagers: 750 Years of Life in an English Village by James Brown

- Gamlingay Eco Hub

- Gamlingay Records

- Gamlingay & District History Society

- A Pictorial History of an English Village

- Community website

- Brycchan Carey's Gamlingay pages

- Parish Council website

- Gamlingay Environmental Action Group

- Gamlingay at Curlie