Garbage can model

The garbage can model (also known as garbage can process, or garbage can theory) describes the chaotic reality of organizational decision making in an organized anarchy.[2] The model originated in the 1972 seminal paper, A Garbage Can Model of Organizational Choice, written by Michael D. Cohen, James G. March, and Johan P. Olsen.[1]

Organized anarchies are organizations, or decision situations (also known as choice opportunities), characterized by problematic preferences, unclear technology, and fluid participation.[1] While some organizations (such as public, educational, and illegitimate organizations) are more frequently characterized by these traits of organized anarchy, the traits can be partially descriptive of any organization, part of the time.[1][3]

Within this context, of an organized anarchy view of organizational decision making, the garbage can model symbolizes the choice-opportunity/decision-situation (for example: a meeting where ideas are discussed and decided on) as a "garbage can" that participants are chaotically dumping problems and solutions into, as they are being generated. The "garbage can" term's significance is best understood by considering the manner in which items in a trash can are organized, which is a messy, chaotic mix. The model portrays problems, solutions, and participants/decision-makers as three independent "streams" that are each generated separately, and flow disconnected from each other. These three streams only meet when the fourth stream of choice opportunity arises, as a garbage can, for the streams to flow into. The mix of garbage (streams) in a single can (choice opportunity) depends on the mix of cans available, on the labels attached to each can, and on what garbage is currently being generated. The mix of garbage in a single can also depend on the speed at which the garbage is collected and removed from the scene, for example, how long before problems, solutions, and/or participants move on to other choice opportunities, or, depending on how long the current choice opportunity remains available.[1] This anarchic view of decision making contrasts with traditional decision theory.

Organized anarchy

Organized anarchies can be characterized by a sense of chaos and dynamism. Problems and solutions are loosely coupled. Proposed solutions change during bargaining. All participants involved do not get the chance to fully participate, and have limitations on their time and energy. Many things happen at once, all competing with each other for attention.[2] Amongst the confusion, participants try to make sense of their role in the organization.[2]

General properties

The behavioral theory of organized anarchy views organizations, and/or decision-situations/choice-opportunities, as generally characterized by the three properties of problematic preferences, unclear technology, and fluid participation (detailed below).[2] These properties of organized anarchy are characteristic of any organization in part, part of the time.[1]

Problematic preferences

The organization has no clear preference or guidelines.[1] It operates on the basis of a variety of inconsistent and ill-defined preferences, goals, and identities.[2] The organization can be described more accurately as a loose collection of ideas, rather than as a coherent structure. Organizations discover their preferences through actions, more than actions are taken on the basis of preferences.[1] It is unclear which problems matter, and which do not.[2]

Unclear technology

The organization's processes are not understood by the organization's own members. The organization operates based on trial and error procedures, learning from accidents of past experiences, and pragmatic inventions of necessity.[1] It is not clear what the consequences are for proposed solutions, or how to solve problems with solutions that lack evidence.[2]

Fluid participation

Participants vary in how much time and effort they commit to different domains. Participant involvement also varies, depending on the time. Consequently, the boundaries of the organization are continuously uncertain and changing. Audiences and decision makers for any type of choice change suddenly and unpredictably.[1]

Meaning making

Organizations can be viewed as vehicles for solving problems, or structures where conflict is resolved through bargaining. However, organizations also provide procedures through which participants gain an understanding of what they are doing and what they have done.[1] Organizations, especially organized anarchies, may have difficulty creating their collective platform and identity.[2] In situations of ambiguity, decision making moves away from ideas of reality, causality, and intentionality, to thoughts of meaning. Therefore, decisions become seen as vehicles for constructing meaningful interpretations of fundamentally confusing worlds, instead of outcomes produced by comprehensible environments.[2] As the complexity of decision situations increase so that they more closely resemble reality, they become meaning generators instead of consequence generators.

Organized anarchies need structures and processes that symbolically reinforce their espoused values, that provide opportunities for individuals to assert and confirm their status, and that allow people to understand to which of many competing claims on their attention they should respond. They require a means through which irrelevant problems and participants can be encouraged to seek alternative ways of expressing themselves so that decision-makers can do their jobs. They should also be able to “keep people busy, occasionally entertain them, give them a variety of experiences, keep them off the streets, provide pretexts of storytelling, and allow socializing” (Weick’s The Social Psychology of Organizing, p. 264).

Birnbaum, Robert (1989). "The Latent Organizational Functions of the Academic Senate: Why Senates Do Not Work But Will Not Go Away". The Journal of Higher Education. Vol. 60, No. 4. p. 439

Hence, we understand organized anarchies as meaning makers that we need within organizations so that we can feel like we have reasons and identities for which to be present at the organization and to address many types of concerns, such as in meetings, where the issues may or may not be relevant to the existing topic of discussion.[2] Within this perspective, an organization is a collection of choices seeking problems, issues and feelings seeking decision situations where they can be raised, solutions seeking issues to which they may be able to solve, and decision makers seeking out work.[1]

The Garbage Can Model

Whereas the theory of organized anarchy provided a larger view to describe how organizations and decision situations function, the garbage can model focuses in on how decisions get made within these organized anarchies.[2][1] The model details what elements are involved in the decision-making process, how the outcomes are generated, and who/what is able to access this interaction.

Decision streams

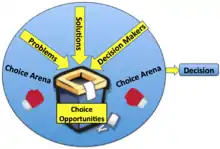

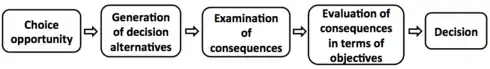

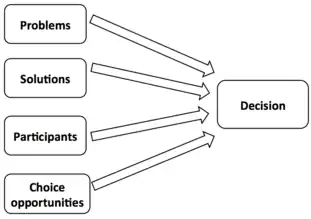

The garbage can model views decisions as outcomes of four independent streams (detailed below) within organizations. Prior to the garbage can model, the decision process was imagined very differently, as visually displayed, based on references from the foundational literature, in the figures below.[1]

Problems

Problems arise from people both inside and outside of the organization, and for many different reasons, all consuming attention. Examples may include family, career, distribution of status and money, or even current events in the media.[1] These problems do not need to be real, or actually important, but only to be perceived as such by the decision makers.[2]

Solutions

Solutions are an individual's or a collective's product. Examples may include ideas, bills, programs, and operating procedures.[2] None of the solutions need to pertain to an existing problem. Instead, participants use the solutions generated to actively seek out problems that the solutions may be able to solve.[1]

Participants

Participants have other demands on their time, and actively arrive to, and leave from, the decision-making process. They may also have different preferences for different solutions.[1]

Choice opportunities

Choice opportunities give the organizations chances to act in ways that can be called decisions. These opportunities occur regularly, and organizations are able to determine moments for choice. Examples may include the signing of contracts, hiring and firing employees, spending money, and assigning tasks.[1][2]

The first three streams of problems, solutions, and participants, flow into the fourth stream of choice opportunities, and mix based on chance, timing, and who happens to be present.[2]

The decision arena

While the first three streams of problems, solutions, and participants, meet in the stream of choice opportunity (for example, a choice to hire a new employee), the decision/choice arena is the larger domain where all four of these streams meet.[2][1] This arena can be the type of organization (government, school, university) or the greater setting in which this interaction is occurring. For example, a board or committee may be a choice arena, while the committee's annual elections may be a choice opportunity. Choice opportunities may also move between different choice arenas, such as a decision being passed between committees, or departments.[2]

Decision outcomes

The outcomes of how the four streams mix in a choice arena can vary. Sometimes decisions are made. Other times no decisions are made. Still other times, decisions are made, but do not address the problem that they were meant to solve.[2][1]

Resolution

Resolution occurs when the choices taken resolve the problem that was being addressed. This success occurs when problems arise in choice opportunities, and the decision makers present have the energy/ability to properly address the problems' demands.[1][2]

Oversight

Oversight occurs when a decision is taken before the problem reaches it. This happens when choice opportunities arrive and no problems are attached to them. This may be due to problems being attached to other choice arenas at the moment. If there is sufficient energy available to make a choice quickly, participants will make the choice and move on before the relevant problem arrives.[1][2]

Flight

Flight occurs when a decision is taken after the problem goes away. This happens when problems are attached to choice opportunities for a period of time and exceed the energy of their respective decision makers to stay focused on the problem. The original problem may then move to another choice arena. Examples are tabling, or sending decisions to subcommittees, where the problems may not get attached to solutions.[2][1]

Early implications

The Fortran model simulations, used in the original paper, found that, most often, decisions are not made to resolve problems.[1] Decision-making processes were found to be very sensitive to variations in energy and time.[1] Decision makers and problems were also found to seek each other out, and continue to find each other.[1]

Three key aspects of the efficiency of the decision process are problem activity, problem latency, and decision time.[1] Problem activity is the amount of time unresolved problems are actively attached to choice situations. This is a rough measure of the potential for decision conflict in an organization.[1] Problem latency is the amount of time problems spend activated but not linked to choices.[1] Decision time is the persistence of choices.[1] Good organizational structures would be assumed to keep problem activity and problem latency low by quickly solving problems with choices. Notably, this result was not observed in the garbage can model.[1]

The model's processes are very interactive, and some phenomena are dependent on specific combinations of other structures at play. Important problems were found more likely to be solved than unimportant ones, and important choices were less likely to solve problems than unimportant ones.[1]

Model constraints

Access structures and deadlines provide limitations on what can enter into the garbage can model's processes.[1][2]

Access Structure

.jpg.webp)

Access structures are the social boundaries that influence which persons, problems, and solutions are allowed access to the choice arena.[2]

Unrestricted/democratic access

The loosest access structure, unrestricted/democratic access allows all problems, solutions, and people to enter. Any active problem has access to any active choice.[1] This creates more energy, but also permits problems, solutions, and participants to interfere with each other. Conflict and time devoted to problems (anarchy) are increased.[2] An example could be an open forum, town hall, or general body meeting.

Hierarchical access

Hierarchical access gives priority entry to important actors, problems, and solutions. Both choices and problems are arranged in a hierarchy so that important problems (having low numbers) have access to many choices, and

important choices (also having low numbers) are accessible to only important

problems.[1] An example could be making big decisions in an executive

meeting/committee, while small decisions are left for the general population.[2]

.jpg.webp)

Specialized access

Specialized access happens when only special problems and solutions can gain entry to certain meetings. Specific specialists have access to specific choices that fit their expertise.[2] Each problem has access to only one choice and each choice is accessible to only two problems.[1] Hence, choices specialize in the types of problems that can be connected to them.[1] An example could be computer specialists in a technology committee addressing technical issues.

Deadlines

Deadlines characterize temporal boundaries, the timing of decision arenas and what flows access them.[2] Constraints include arrival times of problems (seasonal or weather issues, such as a heat wave, or a blizzard), solutions (time delayed, for example by 1 or 5 year plans), participants (determined by the timing of business days, school semesters, etc.), and choice opportunities (for example, meetings based on budget cycles, or student admissions).

Decisions arise from the constraints of access structures and deadlines interacting with the time-dependent flows of problems, solutions, and participants.[2]

Origins of the garbage can model

While still a doctoral student at the University of Bergen in Norway, Johan P. Olsen came to the University of California, Irvine as a visiting scholar from 1968 to 1969. At that time, James G. March was both the Dean of the School of Social Sciences (1964–1969), and a professor of psychology and sociology at the University of California, Irvine (1964–1970). Coinciding with the time of Olsen's visit, and March's last year serving as a dean, Michael D. Cohen was a doctoral student at the University of California, Irvine, and was just beginning his work as a research assistant to March. All three scholars were present at the right time, to witness the university conduct a search process to hire a new dean. Ultimately, the search process ended with none of the potential candidates being chosen, and the head of the search committee taking the position of dean. During an interview, Olsen describes the chaotic decision-making process that he observed at the university throughout this search process, and how it served as a foundational experience for the three scholars to later collaborate and produce their model.[4] Olsen explains in this interview how topics previously considered to be important to the decision-making process, such as if the actors were reasonable or rational, actually proved to be less important, and were instead trumped by issues such as time constraints of the participants involved. An example provided was a professor being present in one meeting, only to be absent from the following meeting due to professional travel commitments, which can be common for university faculty. This prompted Olsen to consider a contextual model of decision making, one that examined the ability to make calculations and implement them, as opposed to models that focused on motivation. Olsen observed decision makers give each other head nods, and other non-verbal communication, in meetings, and noted the possible communication, or miscommunication this may have entailed. Olsen also highlighted how the search committee's decision-making process was affected by misinterpreting the silence of the current dean (March) regarding applicants as a sign for lack of support, when in fact this was not an accurate interpretation of the dean's preferences. Olsen, therefore, gained an interest to examine collective, as opposed to individual, decision making, and how routines and chance may affect the decision-making process.[4] All of these factors would lead into the development of the garbage can model.

By 1972, March, Cohen, and Olsen had all found their way from the University of California, Irvine to Stanford University, in the positions of professor, post-doctoral fellow, and visiting professor, respectively. That year, they published the seminal paper A Garbage Can Model of Organizational Choice.[1] In this paper, the authors used version 5 of the programming language Fortran to translate their ideas into a computer simulation model of a garbage can decision-making process.[1]

Practical applications

The model enables choices to be made and problems resolved, even when an organization may be plagued by conflict, goal ambiguity, poorly understood problems that come and go, variable environments, and distracted decision makers.[1] There are many situations where the garbage can process of decision making cannot be eliminated, and in some of these instances, such as research, or family, the garbage can process should not be eliminated.[1]

Knowing the characteristics of an organizational anarchy and a garbage can model can help people to properly identify when and where these phenomena exist, and approach them strategically. Understanding how these decision arenas operate provide tools to successfully manage what could otherwise be a problematic decision-making process.

Management styles

Organized anarchies can be managed, to use the garbage can model to your advantage. Three different management styles can be used, as detailed below.

Reformer

A reformer eliminates the chaotic garbage can elements from decisions.[2] This creates greater order and control, which centralizes and rationalizes the organization.[2]

Enthusiast

In contrast to the reformer, the enthusiast tries to discover a new vision of the decision making within garbage can processes.[2] The enthusiast realizes that the planning is in large part symbolic, and is an excuse for participants to interact and generate meaning.[2] It allows participants to feel a sense of belonging, and to learn about identities and views.[2] Once the enthusiast understands that the decision arena is more for sense-making and observations, than for making decisions, temporal sorting can be used as a way to organize attention. The temporal order of topics presented can suggest what is of more concern for collective discussion. Flows of problems and solutions are viewed as a matching market, where energies and connections are mobilized.[2] Assessing who is present, and where time and energy are sufficient, allows the enthusiasts to advance their case most effectively. Characteristics of the garbage can model that were seen by others as disadvantages, such as flexible implementation, uncoordinated action, and confusion, are viewed as advantages by the enthusiast.[2]

Pragmatist

The pragmatist tries to exploit the anarchy inherent in the garbage can processes to further personal agendas.[2] Timing can be manipulated to have solutions arrive when attention is low. The meeting can be arranged in an order that is personally favorable, where items that are desired to be discussed are placed at the top of the agenda, and items that need to be passed, in which discussion is not desired, are placed at the bottom of the agenda, so that the decision can be rushed through when there is not enough time for discussion.[2] The pragmatist pays attention to fluctuations in interests and participant involvement, so that when certain individuals are not present, it can be easier to advance issues and solutions that may have otherwise been opposed by different participants.[2] Initiatives that are entangled with other streams can be abandoned, and if an unfavorable topic arises, the system can be overloaded to protect the pragmatist's interests.[2] This can be accomplished by bringing up different problems and solutions, which will slow the decision-making process down and make it more complex.[2] Other choice opportunities (meetings) can also be proposed to lure problems and participants away from choices that are of interest, in the process gaining time for the pragmatists to address the issues of their concern.[2]

Multi-disciplinary impact

The garbage can model can be especially helpful in explaining all types of meetings where problems and solutions are fluidly discussed.[2] The model fits well with almost any decentralized social system attempting to address issues, and the model is continuously finding its way into new domains.[1] For example, across a sample of firms involved in hydrocarbon megaprojects, researchers found that problems given the most attention are different from those responsible for budget overruns, and that the attribution of reasons for these overruns differ between project owners and supply chain firms.[5] These inconsistencies are addressed by the garbage can model. Also, trade fairs have been found to be organizational forms that have permeable, fluid participation, and diversified and spontaneous in terms of individual goals and actions, once again displaying traits characteristic of the model.[6]

Several fields such as higher education, the policy-government world, and academic research, are discussed further below.

Higher education

The American college or university is, in a way, a prototypical organized anarchy.[7] Students constantly enter and leave the institution, and the faculty and staff working there for longer periods of time may have many competing demands on their attention and resources, such as course instruction, research, and conference travel. Different academic departments may prioritize different, and even competing, goals for the university. University senates, in particular, provide an opportunity to see the characteristics of organized anarchy and the garbage can model in action.[3] These senates largely serve symbolic meaning making functions for participants to express themselves through their membership, commitment to professional values, and maintaining relationships.[3] Often, committees that report to the senate take so long to work on their issue, due to constraints on participant time, or difficulty matching problems with solutions, that by the time the committee produces anything, the issue has already passed on.[8] Hence, this provides an example for how the decision was already made, by the garbage can model's decision outcome of flight, where decisions are taken after problems have already gone away. The university senate is known for this latency.[3]

Public policy

Government can be viewed as an organized anarchy.[9] The actors (politicians) can consistently change with election cycles. There are multiple, often competing, preferences. Problems arise from current events, and can gain or lose focus based on media coverage. Policies may be proposed by think tanks or lobby groups, but these policies may not gain attention until the right situation arises that promotes their relevance. John W. Kingdon built on the ideas of organized anarchy to examine these dynamics in his "Multiple Streams Approach", adapted for the field of public policy[9] Kingdon renamed some of the terms familiar in the garbage can model. Problems remain termed as problems, but solutions became renamed as policies, and participants were termed as politics. These streams converge, or, as Kingdon says, couple, in the policy window (choice opportunity). Ambiguity, competition, an imperfect selection process, actors having limited time, and decision-making processes being neither "comprehensively rational" nor linear, are several key elements of multiple streams approach that clearly reflect the general properties of organized anarchy.[10]

Research in psychology

The research process in the field of social sciences, particularly in psychology, can be interpreted as an organized anarchy.[11] The academic field of psychology is much more a loose collection of ideas and theories, rather than a coherent structure with a shared intellectual paradigm. Technologies used to conduct research may not be fully understood. Methods for analyzing data, or conducting research, are taken from other fields when the need arises. Participation in the research process is fluid, with some research being done by students, other research being done by professors who may publish one or a few articles and then not continue as a researcher, and other research being done by people who make the research process their life-long profession. Joanne Martin recognized these characteristics of organized anarchy, and applied an adapted version of the garbage can model to the psychological research process.[11] Martin's model restyled the original model's four streams. Problems took the parameters of theoretical problems. Solutions were seen as the results of the research process. Choice opportunities were understood as the selection of which methodology to use for the research. Finally, the stream for participants was re-termed resources, to reflect that, unlike in organizational decision making, not only were actors required to move the decision/research process forward, but specific intellects and skill-sets could also be required, as well as financing, study subjects, and access to certain environments for conducting the research in. The garbage can model of the psychological research process describes how and why some research topics may go unaddressed, certain theoretical problems may be linked with only a single methodological approach, researchers may continue to work on the same issues throughout their careers, some methods may be seldom applied, and how and why the field may appear to make little progress at times.[11]

Current use and future growth of the model

The garbage can model continues to appear in academic articles, textbooks, and the press, being applied across many diverse domains. Features of organized anarchy have increased in modern times, and many attempts have been made to contribute to the theoretical discourse of the garbage can model by extending it to include new components. For example, fluid participation, a key characteristic of organized anarchy, has greatly increased since the original model was formulated.[12] Some recent research has sought to contribute to the theoretical discourse of the model, by finding leadership style to be a key predictor of decision structure in organized anarchy.[13] Other recent research has found problems with the computer simulation model used in the original article by Cohen, March, and Olsen, suggesting that decision making styles have not been sufficiently analyzed.[14]

In 2012, the volume The Garbage Can Model of Organizational Choice: Looking Forward at Forty was published, containing a collection of papers celebrating 40 years since the original article on the garbage can model was introduced.[15] The papers collected in the volume present theories of organizational decision processes that build on the original garbage can model, at times adding new ideas to create a hybrid extension of the original, and at other times perhaps violating the original model's core assumptions, thereby proposing alternatives to the existing model. Some of these papers attempt to attach elements of economic reasoning based on rational action assumptions onto the model.[15] Many of the volume's chapters address the problem of agency, to which the garbage can model offered a solution based on a temporal, instead of a consequential, ordering of organizational events.[15] Some of the newer models that have been proposed make assumptions returning to a consequential view of decision making, as well as assuming that individual preferences may play a larger role in the process.

The volume's papers collectively suggest that the next logical stage of evolution for the garbage can model may be to directly model complex network dependencies linking participants, solutions, problems, and choice opportunities, or overall, social processes, within organizations.[16][15] Taken as a whole, the volume contributes to defining an intellectual agenda that may well extend far beyond the next forty years of organizational research.[15]

References

- Cohen, M.D.; March, J.G.; Olsen, J.P. (1972). "A garbage can model of organizational choice". Administrative Science Quarterly. 17 (1): 1–25. doi:10.2307/2392088. JSTOR 2392088.

- McFarland, Daniel; Gomez, Charles (2013). "4" (PDF). Organizational Analysis. Coursera. pp. 60–77.

- Birnbaum, Robert (1989). "The Latent Organizational Functions of the Academic Senate: Why Senates Do Not Work But Will Not Go Away". The Journal of Higher Education. 60 (4): 423–443. JSTOR 1982064.

- Olsen, Johan (2011). "The Origins of the Garbage Can Model". YouTube.

- Steen, J.; Ford, J. A.; Verreynne, M. (2017). "Symbols, Sublimes, Solutions, and Problems: A Garbage Can Model of Megaprojects". Project Management Journal. 48 (6): 117–131. doi:10.1177/875697281704800609. S2CID 115800765.

- Bathelt, Harald; Gibson, Rachael (2015). "Learning in 'Organized Anarchies': The Nature of Technological Search Processes at Trade Fairs". Regional Studies. 49 (6): 985–1002. doi:10.1080/00343404.2013.783691. hdl:1807/75457. S2CID 53460642.

- Cohen, M.D.; March, J.G. (1974). Leadership and Ambiguity: The American College President. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 3.

- Baldridge, J.V.; Curtis, D.V.; Ecker, G.; Riley, G.L. (1978). Policy Making and Effective Leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. p. 80.

- Kingdon, John W. (2003). Agendas, alternatives, and public policies, second edition. London, UK: Longman.

- Cairney, Paul; Jones, Michael D. (2016). "Kingdon's Multiple Streams Approach: What Is The Empirical Impact of this Universal Theory?". The Policy Studies Journal. 44: 37–58. doi:10.1111/psj.12111. hdl:1893/23014.

- Martin, Joanne (1981). "A Garbage Can Model of the Psychological Research Process". The American Behavioral Scientist. 25 (2): 131–151. doi:10.1177/000276428102500203. S2CID 144113533.

- Harrison, J. R.; Carroll, G. R. (2006). Culture and demography in organizations. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Zhu, Y.; Kindarto, A. (2016). "A garbage can model of government IT project failures in developing countries: The effects of leadership, decision structure and team competence". Government Information Quarterly. 33 (4): 629–637. doi:10.1016/j.giq.2016.08.002.

- Nobuyuki, Inamizu (2015). "Garbage Can Code: Mysteries in the Original Simulation Model". Annals of Business Administrative Science. 14: 15–34. doi:10.7880/abas.14.15.

- Lomi, A.; Harrison, J.R. (2012). The Garbage Can Model of Organizational Choice: Looking Forward at Forty (Vol. 36 ed.). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. pp. 3–17. doi:10.1108/S0733-558X(2012)36. ISBN 978-1-78052-712-3.

- Robins, G. L.; Pattison, P. (2005). "Interdependencies and social processes: Generalized dependence structures". In Carrington, P. J.; Scott, J.; Wasserman, S. (eds.). Models and methods in social network analysis. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 192–214. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511811395. ISBN 9780511811395.

External links

- Bell, S. (2012, April 26) "Learning to be a Better Decision Maker | Leading From the Library". Library Journal. Retrieved from https://lj.libraryjournal.com/2012/04/opinion/leading-from-the-library/learning-to-be-a-better-decision-maker-leading-from-the-library/#_

- Hollands, F., Griffin, A., Saxberg, B. (2017, July 10). “Analysis: Ed tech decision makers are under pressure in higher education”. The 74 million. Retrieved from https://www.the74million.org/article/analysis-ed-tech-decision-makers-are-under-pressure-in-higher-education/

- Menon, T. (2016, September 26). “Macromanagement is just as bad as micromanagement”. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/ideacast/2016/09/macromanagement-is-just-as-bad-as-micromanagement.html

- ScroogeMC (2016, December 20). “AMZN stock: Why Amazon.com Inc’s disruption phase is over now”. Amigo Bulls. Retrieved from https://amigobulls.com/articles/amzn-stock-why-the-disruption-is-over-for-amazon-com-inc

- Teferra, D. (2014, July 18). “‘Organized anarchy’ – The enduring paradigm of university management”. University World News. Retrieved from http://www.universityworldnews.com/article.php?story=20140716075612402