Garðaríki

Garðaríki (anglicized Gardariki or Gardarike)[7][8] or Garðaveldi was the Old Norse term used in the Middle Ages for the lands of Rus'.[9][10][12][note 1] According to Göngu-Hrólfs saga, the name Hólmgarðaríki (also used as a name for Novgorodian Rus')[20][21] was synonymous with Garðaríki, and these names were used interchangeably in several other Old Norse stories.[22]

As the Varangians dealt mainly with the northern lands of Rus', their sagas regard the city of Hólmgarðr/Hólmgarðaborg (usually identified with Novgorod)[note 2][43][44] as the capital of Garðaríki.[note 3][58][60][61] Other important places of Garðaríki mentioned in the sagas that have generally been identified with well known historical towns are Aldeigja/Aldeigjuborg (Ladoga),[62][63][64] Kœnugarðr/Kænugarðr (Kiev),[66][67] Pallteskja/Pallteskia (Polotsk),[68][69][70] Smaleskja/Smaleskia (Smolensk),[71][72] Súrdalar (Suzdal),[73] Móramar (Murom),[74] and Rostofa (Rostov).[3][1][76][77][78]

At least seven of the Varangian runestones, G 114,[79] N 62,[80] Sö 148,[81] Sö 338,[82] U 209,[83] U 636,[84] and Öl 28,[85] refer to Scandinavian men who had been in Garðar.[86][87][88][89]

Etymology

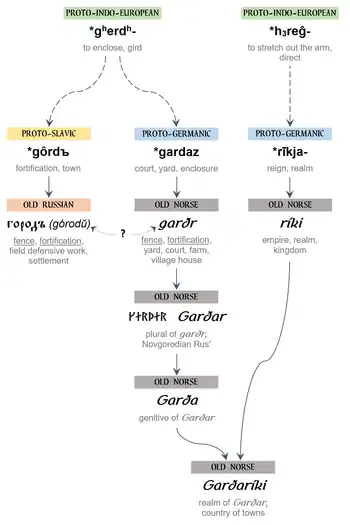

The word Garðaríki, which first appeared in Icelandic sagas in the twelfth century,[114] could stem from the words Garðar[115] and ríki (an empire, realm, kingdom)[92][90][note 4] according to the common Scandinavian pattern for state formations X+ríki.[117] Garða is the genitive form of Garðar,[105][112] therefore the compound Garðaríki could be translated into English as "the kingdom of Garðar" or "the empire of Garðar".[113][106] The name Garðar itself was used in skaldic poems, runic inscriptions and early sagas up to the twelfth century to refer to the lands to the east of Scandinavia populated by the Rus' people,[118][120] primarily to Novgorodian Rus'.[16]

Garðar is a plural form of the Old Norse word garðr which referred to 1) a fence; 2) a fortification; 3) a yard; 4) a court; 5) a farm; 6) a village house,[121][122][94][note 5] while the related Old Russian word городъ[note 6] referred to 1) a fence; 2) a fortification; 3) a field defensive work; 4) a settlement.[95][128] Since there is an overlapping meaning among the ones these related words once had ("a fence, a fortified place"), both garðr and городъ could mean the same at one time in the past. Thus, some researches interpreted Garðar as a collective name for Old Rus' towns[130][131] encountered by Scandinavians on their way from Lyubsha and Ladoga down the Volkhov River into other Slavonic lands. The younger toponym Garðaríki could mean "the realm of towns", or "the country of towns".[133]

Legendary kings

- Odin (Hervarar saga)[135]

- Sigrlami (Hervarar saga)[135]

- Rollaugr or Hrollaugr (Hervarar saga)[136][137]

- Ivar Vidfamne (Hervarar saga)

- Ráðbarðr (Sögubrot)[139]

- Hreggviðr (Göngu-Hrólfs saga)[140]

- Hálfdan Brönufostri (king of Svíþjóð hin kalda in Sörla saga sterka)[141][note 7]

- Vissavald (king from Garðaríki, Óláfs saga Tryggvasonar)[146]

- Hertnið (king of Ruziland, Þiðreks saga)[47]

See also

Notes

- The original name for the lands of Rus', particularly of Novgorodian Rus', in Swedish, Norwegian and Icelandic sources, including runic inscriptions, poetry of skalds and sagas, was the toponym Garðar.[14][15][16] First seen in the poem Óláfsdrápa composed by Hallfreðr Vandræðaskáld in 996.[17] The toponym is based on the root garð- with a wide range of meanings.[18][19]

- Today's Veliky Novgorod encompasses Gorodishche, an important administrative and trade center of the 9th century, which was originally known by the Scandinavians as Hólmgarðr.[27][28][29] Although its Old Norse name was then transferred to Novgorod, Gorodische later regained some of its importance and served as the residence of Novgorodian princes.[30][31][32] Holmgarðr or Hólmgarðaborg[34] is generally identified with Novgorod in literature[35][36][37][38] and research articles.[39][40][41][42]

- Þiðreks saga mentions King Hertnid, who ruled Ruziland and whose capital was Hólmgarðr.[47] Örvar-Odds saga says that all the kings of Garðaríki paid tribute to King Kvillánus who resided in Hólmgarðr.[48] Hervarar saga mentions King Hrollaug, the most powerful king of that time, who resided in Hólmgarðr.[49] Eymundar saga tells of King Jarizleifr as a king residing in Hólmgarðr, the best part of Garðaríki, and ruling over the whole Garðaríki.[50] Göngu-Hrólfs saga represents Hólmgarðaríki (i.e. the realm of Hólmgarðr, the kingdom belonging to Hólmgarðr as its capital)[51] as another name for Garðaríki.[52] Two versions of Göngu-Hrólfs saga[53][54] speak of Hólmgarðaborg as the main seat of the king of Garðar, equating it to Novgorod of their time (Nógarðar).[55] Þjalar-Jóns saga represents all minor kings as liege lords of the King of Hólmgarðr.[56][57]

- Old Norse ríki, Old High German rīhhi, and Old English rīce stem from the Proto-Germanic *rīkja- meaning "kingdom, reign, realm"[97][100][116]

- Old Norse garðr, Old High German gart(o) ("garden, enclosure"), as well as Old English ġeard ("courtyard, enclosure") go back to the Proto-Germanic *gardaz or *ʒarðaz[123][98][107][124][125]

- Old Russian городъ,[96][126] Old Church Slavic градъ, and Russian город stem from the Proto-Slavic *gȏrdъ meaning "fortification, town".[91][127]

- Some scholars linked Svíþjóð hin kalda or "Sweden the Cold" to the ancient Sarmatia and assumed that Gardariki was located there.[142][143][144][145]

Citations

- Melnikova 1986, p. 38: "Полоцк, Полтеск — Pallteskja, Смоленск — Smaleskja ... Móramar (Муром) и Súrdalar (Суздаль) [Polotsk, Poltesk — Pallteskja, Smolensk — Smaleskja ... Móramar (Murom) and Súrdalar (Suzdal)]"

- Melnikova 1986, p. 43: "Rostofa - Ростов [Rostofa - Rostov]"

- Müllenhoff 1865, p. 346: "Kœnugarðr (Kiew), Palteskia (Polotzk) und Smaleskia (Smolensk)"

- Bugge 1906, p. 250: "Rußland selbst und mehrere russische Städte tragen in den isländischen Sagas nordische Namen, z.B. Garđar oder Garđaríki ″Rußland″, Holmgarđr ″Nowgorod″, Aldeigjuborg ″Altladoga″, Kœnugarđr ″Kiew″, Surdalar ″Susdal″, Smalenskia ″Smolensk″ und Palteskia. [Rus' itself and several Rus' towns are called by their Nordic names in the Sagas, e.g. Garđar or Garđaríki ″Rus'″, Holmgarđr ″Novgorod″, Aldeigjuborg ″Old Ladoga″, Kœnugarđr ″Kiev″, Surdalar ″Suzdal″, Smalenskia ″Smolensk″ and Palteskia.]"

- Duczko 2004, p. 1: "The state of the Eastern Slavs—Russia, or Rhosia according to the Byzantines of mid-tenth century—was called in the medieval Norse literature Gardariki, or in the earlier, Viking-age sources just Gardar, a term originally restricted to the non-Slav territory of Ladoga-Ilmen."

- Skeie 2021, p. 72: "Gardarike, or “the cities”, an umbrella term for the multi-ethnic trading and craft centres located along the Russian rivers."

- Dølo 2017, p. 87: "I de gamle norrøne kildene blir det reelle riket Rus beskrevet som Gardarike. Rus besto av flere riker løst knyttet til hverandre. Geografisk er det snakk om hovedsakelig Novgorod-området i dagens Russland og byer rundt Dvina elven. [In the Old Norse sources, the real kingdom of Rus is described as Garðaríki. Rus consisted of several kingdoms loosely connected to each other. Geographically, it is mainly about the Novgorod area in today's Russia and cities around the Dvina river.]"

- Store Norske Leksikon 2020.

- de Vries 1977, p. 156: "Garðaríki, älter auch Garðar 'name des Wikingerreiches in Russland'."

- Gade & Whaley 2009, p. 279: "Garðar or Garðaríki is Novgorod (Hólmgarðr) and its territory in north-west Russia."

- Duczko 2004, p. 60: "These two original centres of Rus were Staraja Ladoga and Rurikovo Gorodishche, two points on the ends of an axis, the Volkhov, a river running for 200 km between two lakes, from the Ilmen in the south to the Ladoga in the north. This was the territory that most probably was originally called by the Norsemen Gardar, a name that long after Viking Age was given much wider content and become Gardariki, a denomination for whole Old Russian State."

- Pritsak 1981, p. 366: "In the older sources, such as the scaldic poetry and the King's sagas, the usual ON name for Rus' (especially Novgorodian Rus') was Garðar, the plural form of Garðr."

- Jackson 2003, p. 37: "The earliest fixation of Garðar, as a designation of Rus, is found in the second strophe of Óláfsdrápa, a poem composed in 996 by the Icelandic skald Hallfreðr Vandræðaskáld (died ca. 1007)."

- de Vries 1977, p. 156.

- Jackson 2003, p. 39.

- Melnikova 2001, p. 72: "наименование Holmgarđr, особенно во множественном числе Holmgarđar, не раз употреблялось для обозначения Новгородской Руси, и в сагах о древних временах появляется даже композит Holmgarđaríki [the name Holmgarđr, especially in its plural form Holmgarđar, was repeatedly used as a designation for Novgorodian Rus', and even the compound Holmgarđaríki emerges in legendary sagas]"

- Fritzner 1891, p. 37: "holmgarðaríki, n. det til Holmgarðr som dets Hovedstad hørende Rige. [Holmgarðaríki, n. the kingdom belonging to Hólmgarðr as its capital.]"

- Mägi 2018, p. 158: "Several other stories of the components of Garðaríki, or narratives where the name Garðaríki was used interchangeably with Holmgarðaríki, these terms indicating presumably the same area, probably relied on old oral tradition. In the beginning of the Saga of Göngu-Hrólf it was specified that King Hreggvidr reigned in "...Holmgarðaríki, which some people call Garðaríki."

- Price 2000, p. 265: "The settlement established in the ninth century has been known since the 12th century as Gorodišce, a name meaning “deserted fortress” and coined with respect to its successor (“Novgorod” means “new fortress”);"

- Price 2000, p. 265: "It was probably Gorodišce that the Norse referred to as Hólmgarðr, the “settlement on the islands”."

- Nosov 1987, p. 76: "The Ryurik Gorodishche existed, undoubtedly, in the mid-9th century and was probably founded even earlier."

- Price 2000, p. 268: "The beginnings of Novgorod can be dated archaeologically to the early tenth century (even though the name is used in the Russian Primary Chronicle to refer to the ninth-century settlement at Lake Ilmen, it is likely that prior to the 920s it is Gorodišce that is meant). Settlement seems to have shifted gradually from the latter island fortress, which after a century of abandonment was later reoccupied as the seat of the prince of Novgorod."

- Melnikova 1998, p. 654: "It seems justifiable to suppose that originally the name Hólmgarðr designated the Gorodishche settlement and was transferred to Novgorod after it gained superiority in the region."

- Nosov 1987, p. 73: "During the existence of the Old Russian state Gorodishche served as the residence of Novgorodian princes who were squeezed out of the city by the developing republican system."

- Fritzner 1891, p. 37: "holmgarðaborg, f. = Holmgarðr."

- Clunies Ross 2017, p. 298: "Ingigerðr, daughter of King Hreggviðr of Hólmgarðaríki (Novgorod)."

- Clunies Ross 2017, p. 301: "Hilmir, sonr Sturlaugs, mun stýra Hólmgarði ...The prince, son of Sturlaugr, will govern Novgorod;"

- Hjardar & Vike 2016, p. 119: "The trading centre of Novgorod, or Holmgard as the Vikings called the town, was founded on an island in the River Volkhov."

- Peterson 2016, p. 223: "Holmgarðir [or Holmgarðr] being the Old Norse name for Novgorod, a term well understood in Viking Sweden."

- Jackson 2015, p. 173: "Лучше других городов источникам известен отождествляемый с Новгородом Hólmgarðr [Hólmgarðr, which is identified with Novgorod, appears in the sources more often than other towns]"

- Bugge 1906, p. 244: "Nowgorod (Holmgarđr)"

- Kahle 1905, p. 16: "Hólmgarðr ist die stadt Nowgorod, die hauptstadt des im 9. jh. von schwedischen eroberern gestifteten reiches Garðaríki (Russland). [Hólmgarðr is the city of Novgorod, the capital of the kingdom Garðaríki (Rus') established by Swedish conquerors in the 9th c.]"

- Müllenhoff 1865, p. 346: "so kann Holmgarðr vernünftigerweise doch nichts anders als Novgorod sein [in this way Holmgarðr cannot be any other place but Novgorod]"

- Jackson 2003, p. 45: "The Old Norse place-name Hólmgarðr has traditionally been considered to be the designation of Novgorod".

- Pritsak 1981, p. 369: "The Old Rusʼian “town” (gorod) whose name is attested with certainty in Swedish inscriptions is hulmkarþ Hōlmgarðr, “(Great) Novgorod”".

- Þiðreks saga, chpt. 22: "Hertnið konungr, er í þann tíma stýrði Rúzilandi ...Hólmgarð, er höfuðstaðr er fyrir borgum Hertniðs konungs [King Hertnid, who at that time ruled Ruziland ...Hólmgarð, which is the capital of King Hertnid's cities]".

- Örvar-Odds saga, chpt. 30. Bardagi Odds ok Ögmundar: "Garðaríki er svá mikit land, at þat var þá margra konunga ríki. Marró hét konungr. Hann réð fyrir Móramar; þat land er í Garðaríki. Ráðstafr hét konungr. Ráðstofa heitir þar, er hann réð fyrir. Eddval hét konungr. Hann réð fyrir því ríki, er Súrsdal heitir. Hólmgeirr hét sá konungr, er næst Kvillánus réð fyrir Hólmgarði. Paltes hét konungr. Hann réð fyrir Palteskjuborg. Kænmarr hét konungr. Hann réð fyrir Kænugörðum, en þar byggði fyrst Magok, sonr Japhets Nóasonar. Þessir konungar allir, sem nú eru nefndir, váru skattgildir undir Kvillánus konung. [Garðaríki was such a vast land that it was a kingdom of many kings. Marró was the name of one king who ruled over Móramar, a land in Garðaríki. Ráðstafr was the name of another king, and Ráðstofa was the land where he ruled. Eddval was the name of a king who ruled over the kingdom called Súrsdal, and Hólmgeirr was the name of the king who had ruled over Hólmgarðr before Kvillánus. Paltes was the name of a king who ruled over Palteskjuborg. Kænmarr was the name of another king who ruled over Kænugörðum, where the first settler was Magog, son of Noah’s son, Japheth. All these kings paid tribute to King Kvillánus]".

- Petersen 1847, p. 27: "Eitt sumar sendi hann menn austr í Hólmgarða, at bjóða Hrollaugi konungi barnfóstr, er þá var ríkastr konúngr [One summer he sent men east to Hólmgarðr to offer to bring up the child of King Hrollaug, who was then the most powerful king]".

- Vigfússon 1862, p. 133: "Hon segir Jarizleifi konungi at hann skal bafua hinn æzsla hlut Gardarikis en þat er Holmgard… Jarizleifr konungr skal vera yfir Gardariki [She tells to King Jarizleifr that he will get the best part of Gardariki - Holmgard... King Jarizleifr will rule over Gardariki]".

- Fritzner 1891, p. 37: "holmgarðaríki, n. det til Holmgarðr som dets Hovedstad hørende Rige [Holmgarðaríki, n. the kingdom belonging to Hólmgarðr as its capital]"

- Rafn 1830, p. 237: "...hann átti at ráða fyrir Hólmgarðaríki, er sumir menn kalla Garðaríki [...he ruled over Hólmgarðaríki, which some people call Garðaríki]".

- GKS 2845 Sögubók 1450, p. 54v: "holmg(ar)ða b(or)g e(r) mest(r) atset(r) g(ar)ða k(onung)s þ(at) er nu kallað nog(ar)ðar".

- AM 589 f Sögubók 1450, p. 36r-36v: "i holmg(ar)ða b(or)g er mest(r) atset(r) garða k(onun)gs þ(at) er nu allt kallat nog(ar)ðar ok ruðzala(n)d".

- Rafn 1830, p. 362: "í Hólmgarðaborg er mest atsetr Garðakonúngs, þat er nú kallat Nógarðar [the main seat of the king of Garðar is in Hólmgarðaborg, which is now called Nógarðar]".

- Lavender 2015, p. 92: "All of the minor kings are liege lords of the King of Hólmgarður himself".

- White 2016, p. 91: "Allir smákonungar eru lýðskyldir sjálfum Hólmgarðskonungi [All the kinglets are homages to the king of Hólmgarðr himself]".

- Braun 1924, p. 170: "Weit auffallender ist, daß nach den sǫgur das ganze politische Leben Rußlands sich in Novgorod (Hólmgarðr) konzentriert: es wird überall und immer als Hauptstadt des Reiches aufgefaßt [Far more remarkable is that, according to the sagas, the whole political life of Rus' is concentrated in Novgorod (Hólmgarðr): it is understood everywhere and always as the capital of the realm]".

- Liljegren 1818, p. 204: "Holmgard eller Holmgardaborg, en stad, som af fremlingar mycket besöktes, var deruti hufvudstad och Gardarikes Konungasäte [Holmgard or Holmgardaborg, a city much visited by foreigners, was the capital and seat of the king of Gardariki]".

- Price 2000, p. 264: "Ladoga, known to the Norse as Aldeigjuborg"

- Pritsak 1981, p. 299: "Aldeigja [Old] Ladoga".

- Pritsak 1981, p. 31: "Aldeigjuborg (Old Ladoga), the oldest civic center in Eastern Europe".

- Thomsen 1877, p. 70: "The Old Norse name of Kiev was Kœnugarðr".

- Müllenhoff 1865, p. 346: "Kœnugarðr (Kiew)".

- Melnikova 1986, p. 38: "Полоцк, Полтеск — Pallteskja [Polotsk, Poltesk — Pallteskja]".

- Thomsen 1877, p. 70: "Polotsk was called Palteskja".

- Müllenhoff 1865, p. 346: "Palteskia (Polotzk)".

- Melnikova 1986, p. 38: "Смоленск — Smaleskja [Smolensk — Smaleskja]".

- Müllenhoff 1865, p. 346: "Smaleskia (Smolensk)".

- Melnikova 1986, p. 38: "Súrdalar (Суздаль) [Súrdalar (Suzdal)]".

- Melnikova 1986, p. 38: "Móramar (Муром) [Móramar (Murom)]".

- Bugge 1906, p. 250: "Rußland selbst und mehrere russische Städte tragen in den isländischen Sagas nordische Namen, z.B. Garđar oder Garđaríki ″Rußland″, Holmgarđr ″Nowgorod″, Aldeigjuborg ″Altladoga″, Kœnugarđr ″Kiew″, Surdalar ″Susdal″, Smalenskia ″Smolensk″ und Palteskia. [Rus' itself and several Rus' towns are called by their Nordic names in the Sagas, e.g. Garđar or Garđaríki ″Rus'″, Holmgarđr ″Novgorod″, Aldeigjuborg ″Old Ladoga″, Kœnugarđr ″Kiev″, Surdalar ″Suzdal″, Smalenskia ″Smolensk″ and Palteskia.]"

- Geographical Treatise 1325, p. 1: "Í austanverþri Europa er Garðavelldi, þar er Hólmgarðr ok Pallteskja ok Smálenskja".

- Liljegren 1818, p. 204: "HOLMGARD, eller GARDARIKE, egenteligen så kalladt, tillföll Jarislaf, och utgjorde Novogorod, Ladoga, Bielo-Osero, Rostov och angränsande orter dess område".

- Runor G 114, section Inscription, English: "...in Garðir/Garde, he was with Vivi(?)..."

- Runor N 62, section Inscription, English: "Engli raised this stone in memory of Þóraldr, his son, who died in Vitaholmr - between Ustaholmr and Garðar (Russia)."

- Runor Sö 148, section Inscription, English: "Þjóðulfr (and) Búi, they raised this stone in memory of Farulfr, their father. He met his end in the east in Garðar (Russia)."

- Runor Sö 338, section Inscription, English: "He fell in battle in the east in Garðar (Russia), commander of the retinue, the best of landholders."

- Runor U 209, section Inscription, English: "Þorsteinn made (the stone) in memory of Erinmundr, his son, and bought this estate and earned (wealth) in the east in Garðar (Russia)."

- Runor U 636, section Inscription, English: "Ǫlvé had this stone raised in memory of Arnfastr, his son. He travelled to the east to Garðar (Russia)."

- Runor Öl 28, section Inscription, English: "Herþrúðr raised this stone in memory of her son Smiðr, a good valiant man. Halfborinn, his brother, sits in Garðar (Russia)."

- Pritsak 1981, p. 346: "R i karþum aR. uaR uiue meR::h ... he [Liknat] was in Garðar".

- Pritsak 1981, p. 396: "Þōrstæinn must have spent a long time in Rus' since he managed to accumulate a sizable fortune there (as witnessed by his huge monument, Sö 338)".

- Pritsak 1981, p. 396: "Þōrstæinn, then, was a commander (forungi) of a retinue (lið) in Rus' (i garþum)".

- Pritsak 1981, p. 396: "han fial i urustu austr i garþum ... He fell in action east in Garðar (Rus')".

- Cleasby & Vigfússon 1874, p. 499: "RÍKI, n. ... 2. an empire, kingdom".

- Derksen 2008, p. 178: "*gȏrdъ m. o (c) ‘fortification, town’ ... OCS gradъ ‘wall, town, city, garden’ ... Ru. górod ‘town, city’".

- de Vries 1977, p. 446: "ríki n. ‘macht, herrschaft; reich’ [ríki n. ‘power, rule; empire’]".

- Durkin 2014, section 4.2: "Their common ancestor can be reconstructed fairly certainly as a proto-Germanic adjective *rīkja-, showing a root *rīk- and a suffix *-ja- which forms adjectives. The same suffix could also form nouns, and a noun formation *rīk-ja- is reflected by Old English rīce ‘kingdom’ and by a similar range of congnates, including Old High German rīhhi (> modern German Reich)".

- Jackson 2003, p. 39: "Old Norse garðr has the following meanings: 1) a fence of any kind, a fortification; 2) a yard (an enclosed space); 3) a court-yard, court and premises; 4) a separated farm (in Iceland); 5) a house or building in a country or village (especially in Norway, Denmark and Sweden)".

- Jackson 2003, p. 39: "The Old Russian word, in its turn, has the following meanings: 1) a fence; 2) a fortified place, town walls, a fortification; 3) a field defensive work; 4) a settlement, an administrative and trade center".

- Jøhndal 2018, section 1: "городъ Old Russian, common noun, occurs 322 times in the corpus ... English: city ... Russian: город".

- Koch 2019, p. 90: "KINGDOM, REIGN, REALM. Proto-Germanic *rīkja-: Gothic reiki, Old Norse ríki, Old English rīce, Old Saxon rīki, Old High German rīhhi; Proto-Celtic *rīgyom: Old Irish ríge 'ruling, kingship, sovereignty'".

- Kroonen 2013, p. 169: "OHG gart m. ʻenclosureʼ => *ghordh-o- (IE) ... An o-stem derived from the root *gherdh-".

- Kroonen 2013, p. 175: "*gerdan- s.v. ʻto girdʼ - Go. -gairdan* s.v. ʻid.ʼ => *ghérdh-e- (IE)".

- Kroonen 2013, p. 413: "OHG rīhhi n. ʻreign, realmʼ < *rīkja-".

- Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 199: "*góhrdhos (*góhrthos ~ *góhrdhos) ʻfence, hedge; enclosure, pen, foldʼ ... From *gherdh- ʻgirdʼ which, as a verb, exists only in Germanic".

- Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 199: "ON garðar (pl.) ʻfence, hedgeʼ, court".

- Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 329: "The traditional and still majority view is that in the word for ʻkingʼ we have an agent noun derived from *h3reĝ- ʻstretch out the arm; directʼ".

- Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 199: "OCS gradŭ ʻtown, cityʼ, Rus górod ʻtown, cityʼ".

- Melnikova 2001, p. 70: "Garđaríki, где первая основа Garđa- в форме род. п. мн. ч. дополняется термином ríki «государство» [Garđaríki, where the first stem Garđa- in the genitive plural form is supplemented by the term ríki, "a state"]".

- Nosov 1998, p. 78-79: "Вся же Русь стала называться Gardariki - «страна гардов» [The whole country of Rus' began to be called Gardariki or «the country of gardr's»]".

- Orel 2003, p. 126: "*ʒarđaz sb.m.: Goth gards ‘house, family, court’ (< *ʒarđiz), ON garðr ‘yard’".

- Orel 2003, p. 126: "Slav *gordъ ‘fence, town’".

- Rix & Kümmel 2001, p. 197: "gherdh- ʻumschließen, umgürtenʼ".

- Rix & Kümmel 2001, p. 304: "h3reĝ-, ʻgerade richten, ausstreckenʼ".

- Wachler 1851, p. 442: "GARDHARIKI (mittlere Geographie), ist gebildet aus Gardha, Genitiv der Mehrzahl (Nominativ der Mehrzahl Gardhar), und aus riki, Reich [GARDHARIKI (medieval geography) is formed from Gardha, the genitive plural (the nominative plural Gardhar), and from riki, a realm]".

- Zoëga 1910, p. 195: "GARÐAR, m. pl. Russia; GARÐA-RÍKI, -VELDI, n. the Russian empire.

- Jackson 2003, p. 37: "According to Braun, the name Garðaríki was created by those Icelanders who wrote down sagas from the late twelfth century".

- Jackson 2009, p. 217: "If our sources enable us to do it, we can examine the evolution of place-names in the process of land development. Since the Old Norse-Icelandic material is incomparable from this point of view, we can observe in it the formation of secondary place-names on the basis of the original ones (like Garðaríki from Garðar, or Aldeigjuborg from Aldeigja)".

- Hoad 1988, p. 404: "From the same Gmc. stem are OE. rīce = OS. rīki, MLG. MDu. rīke (Du. rijk), OHG. rīhhi (G. reich), ON. ríki, Goth. reiki kingdom, royal power".

- Braun 1924, p. 194: "Und so entstand in der isländischen Kunstprosa der Ausdruck Garðaríki, nach dem Vorbild von Danaríki, Svíaríki (woraus Sverige) Hringaríki, Raumaríki u. a. m. Volkstümlich war das Wort ursprünglich nicht und ist es auch später nur auf Island durch die Sagaliteratur geworden".

- Jackson 2009, p. 217: "Garðar (generally thought to have been the name of Old Rus)".

- Jackson 2003, p. 37: "In the skaldic poetry of the tenth through the twelfth century, Old Rus is called only by its earliest Old Norse name Garðar. In the runic inscriptions of the eleventh century, the toponym Garðar is used nine times".

- de Vries 1977, p. 156: "garðr 1 m. 'zaun, hof, garten’".

- de Vries 1977, p. 156: "Gewöhnlich zu garðr ‘hof, festung’".

- Kroonen 2013, p. 169: "*garda- m. ‘courtyard’ ... OE geard ‘id.’".

- Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 199: "OE geard enclosure, yard".

- Hoad 1988, p. 548: "OE. ġeard fence, enclosure, courtyard, dwelling, region, corr., with variation of declension, to OS. gardo, (Du. gaard), OHG. gart(o) (G. garten garden), ON. garðr, Goth. gards house, garda enclosure, stall :- Gmc. *ʒarðaz *ʒarðan- rel. to OSl. gradŭ city, garden (Russ. górod town)".

- Trubachyov 1980, p. 37: "др.-русск. городъ ‘ограда, забор’ ... ‘укрепление, крепость, город’ ... ‘защита, надежда’ [Old Russian городъ ‘enclosure, fence’ ... ‘fortification, stronghold, town’ ... ‘defence, hope’]".

- Trubachyov 1980, p. 37: "*gordъ/*gorda/*gordь: ст.-слав, градъ [*gordъ/*gorda/*gordь: Old Slavonic градъ]".

- Thomsen 1877, p. 70: "This word is akin to the Russian gorod’, Old Slavonic grad’, a stronghold, a town, which occurs in all Slavonic languages and cannot therefore well be borrowed from the Old Norse garðr".

- de Vries 1977, p. 156: "…der ältere Name Garðar war vielleicht eine zusammenfassende Bezeichnung von russischen grady oder 'städte'…".

- Braun 1924, p. 196: "Garðar bedeutet also die Gesamtheit der slavisch-russischen Städte mit ihren Bezirken".

- Jackson 2015, p. 172–173.

- Petersen 1847, p. 4: "Konungr hèt Sigrlami, svá er sagt, at hann væri sun Óðins. Hánum fèkk Óðinn þat ríki, sem nú er kallat Garðaríki".

- Petersen 1847, p. 27: "Eitt sumar sendi hann menn austr í Hólmgarða, at bjóða Hrollaugi konungi barnfóstr, er þá var ríkastr konúngr".

- Göttingische Anzeigen 1787, p. 553: "...und Hrollaug, den König in Gardariki (Novogorod)".

- Sögubrot, chpt. 2. Vélræði Ívars konungs: "…Garðaríki. Þar réð fyrir sá konungr, er Raðbarðr hét".

- Rafn 1830, p. 237: "Sva byrjar þessa frásögu, at Hreggviðr er konúngr nefndr; hann átti at ráða fyrir Hólmgarðaríki, er sumir menn kalla Garðaríki…".

- Sörla, chpt. 1. Frá Sörla ok ætt hans: "Í þann tíma, sem Hálfdan konungr Brönufóstri stýrði Svíþjóð inni köldu".

- Jones 2001, p. 248: "Norse sources call geographical Russia Svíþjóð hinn mikla, Sweden the Great, and Garðaríki, the kingdom of (fortified) towns or steads".

- Laing 1844, p.216: "Swithiod the Great, or the Cold, is the ancient Sarmatia; and is also called Godheim in the mythological sagas, or the home of Odin and the other gods".

- Rafn 1852, p.438: "Svethiæ Magnæ (Sarmatiæ)".

- Rafn 1852, p.438: "In ea parte orbis, quæ Europa appellatur, Svethia Magna orienti proxima est, quo ad religionem Christianam propagandam Philippus apostolus venit. Hujus regni pars est Russia, quam nos Gardarikiam appellamus".

- Sturluson 1230, chpt. 48. Dauði Haralds konungs grenska: "Hit sama kveld kom þar annarr konungr, sá hét Vissavaldr, austan or Garðaríki".

References

- "AM 589 f 4to. Sögubók" (in Icelandic). 1450.

- "AM 736 I 4to. Geographical Treatise" (in Icelandic). 1325.

- Blöndal, Sigfús (1924). "Garðaríki". Íslensk-dönsk orðabók [Icelandic-Danish Dictionary] (in Icelandic and Danish). Reykjavík: Prentsmiðjan Gutendsberg. Retrieved 2023-04-10.

- Braun, Friedrich (24 July 1924), "Das historische Russland im nordischen Schrifttum des X. — XIV. Jahrhunderts", in Karg-Gasterstädt, Elisabeth (ed.), Eugen Mogk zum 70. Geburtstag (in German), Halle an der Saale: Max Niemeyer, pp. 150–196

- Bugge, Alexander (1906). "Die nordeuropäischen Verkehrswege im frühen Mittelalter und die Bedeutung der Wikinger für die Entwicklung des europäischen Handels und der europäischen Schiffahrt" [Northern European Communication Ways in Early Middle Ages and the Importance of Vikings for the Development of the European Trade and Navigation]. Vierteljahrschrift für Social- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte (in German). Berlin, Stuttgart, Leipzig. 4. Retrieved 2023-04-07.

- Cleasby, Richard; Vigfússon, Guðbrandur (1874). An Icelandic-English Dictionary. London: Oxford University Press Warehouse. Retrieved 2023-05-06.

- Clunies Ross, Margaret, ed. (2017). "Gǫngu-Hrólfs saga". Poetry in fornaldarsögur. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages. Vol. 8. Turnhout: Brepols N.V. pp. 298, 301. ISBN 978-2503519005.

- Derksen, Rick (2008). Etymological Dictionary of the Slavic Inherited Lexicon. Leiden-Boston: Koninklijke Brill NV. p. 178. ISBN 978-90-04-15504-6. ISSN 1574-3586.

- de Vries, Jan (1977). Altnordisches etymologisches Wörterbuch (in German). Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 156. Retrieved 2022-06-24.

- Dølo, Maria Johnson (2017). 'De andre' i fornaldersagaene. Undersøkelser av den islandske senmiddelalderens mentale verdensbilde ['The others' in the Sagas of the Ancient Time. Investigations of the Icelandic Late Medieval Mental Worldview] (MSc) (in Norwegian). University of Oslo.

- Duczko, Wladyslaw (2004). Viking Rus: Studies on the Presence of Scandinavians in Eastern Europe. The Northern World. North Europe and the Baltic c. 400-1700 AD. Peoples, Economies and Cultures. Leiden, Boston: Brill. ISBN 9789004138742.

- Durkin, Philip (2014). Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191667077.

- Fritzner, Johan (1891). Unger, Carl Rikard (ed.). Ordbog over det gamle norske sprog. Andet Bind. Hl-P [Dictionary of the Old Norwegian Language] (in Danish). Christiania: Den Norske forlagsforening. Retrieved 2023-04-23.

- "Gardarike". Store Norske Leksikon (in Norwegian). 2020-10-07. Retrieved 2022-08-05.

- Gade, Kari Ellen; Whaley, Diana, eds. (2009). "Arnórr jarlaskáld Þórðarson, Haraldsdrápa 17'". Poetry from the Kings' Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages. Vol. 2. Turnhout: Brepols N.V. pp. 279–280. ISBN 978-2503518978.

- "GKS 2845 4to. Sögubók" (in Icelandic). 1450.

- Kroonen, Guus (2013). Lubotsky, Alexander (ed.). Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Germanic. Leiden Indo-European Etymological Dictionary Series. Vol. 11. Leiden, Boston: Brill. ISBN 9789004183407.

- "Kopenhagen". Göttingische Anzeigen von gelehrten Sachen (in German). Göttingen: Dieterich. 1787-04-07. p. 553. Retrieved 2023-03-28.

- Hjardar, Kim; Vike, Vegard (2016). Vikings at War. Oxford, Philadelphia: Casemate Publishers. ISBN 9781612004549.

- Hoad, T. F., ed. (1988). The Oxford Library of Words and Phrases. Vol. III: The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Word Origins. London: Guild Publishing.

- Jackson, Tatjana (2003). "The Image of Old Rus in Old Norse Literature". Middelalderforum. Oslo (1–2): 40. Retrieved 2022-06-19.

- Jackson, Tatjana (2009), "Ways on the "Mental Map" of Medieval Scandinavians", in Heizmann, Wilhelm; Böldl, Klaus; Beck, Heinrich (eds.), Analecta Septentrionalia: Beiträge zur nordgermanischen Kultur- und Literaturgeschichte [Analecta Septentrionalia: Contributions on North Germanic Cultural and Literary History] (in German, English, French, and Icelandic), Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 9783110218701

- Jackson, Tatjana (2015). "Garðaríki and Its Capital: Novgorod on the Mental Map of Medieval Scandinavians". Slověne (in Russian). Moscow. 4 (1): 172. doi:10.31168/2305-6754.2015.4.1.9. Retrieved 2022-06-24.

- Jones, Gwyn (2001). A History of the Vikings. Leiden, Boston: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192801340.

- Jøhndal, Marius L. (2018-09-20). "Gorod" городъ [City]. Syntacticus. Retrieved 2023-07-10.

- Kahle, Bernhard (1905), "Kristnisaga", in Gederschiöld, Gustaf; Gering, Hugo; Eugen, Mogk (eds.), Altnordische Saga-Bibliothek (in German), Halle an der Saale: Max Niemeyer

- Koch, John T. (2019). "Rock art and Celto-Germanic vocabulary. Shared iconography and words as reflections of Bronze Age contact" (PDF). Adoranten. Scandinavian Society for Prehistoric Art. ISSN 0349-8808.

- Lavender, Philip (2015). "Þjalar-Jóns saga: A Translation and Introduction". Leeds Studies in English. Leeds: University of Leeds. XLVI. Retrieved 2023-05-13.

- Liljegren, Johan Gustaf (1818). Skandinaviska Fornålderns Hjeltesagor [Ancient Scandinavian Hero Tales] (in Swedish). Stockholm: Zacharias Haeggström.

- Mallory, J. P.; Adams, Douglas Q., eds. (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. London, Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn. ISBN 1884964982.

- Mägi, Marika (2018). In Austrvegr: The Role of the Eastern Baltic in Viking Age Communication across the Baltic Sea. Leiden: Brill. p. 512. ISBN 9789004363816.

- Melnikova, Elena Aleksandrovna (1986). Drevne-skandinavskie geograficheskiye sochineniya: teksty, perevod, kommentariy Древне-скандинавские географичесие сочинения: тексты, перевод, комментарий [Old Scandinavian Geographic Works: Texts, Translation, Commentary]. The Earliest Sources on History of Peoples of the USSR (in Russian). Moscow: Nauka. ISBN 9785020180826.

- Melnikova, Elena A. (1998). "Runic Inscriptions as a Source for Relation of Northern and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages". In Düwel, Klaus; Nowak, Sean (eds.). Runeninschriften als Quellen interdisziplinär Forschung. Abhandlungen des Vierten Internationalen Symposiums über Runen und Runeninschriften in Göttingen vom 4.-9. August 1995 [Runic inscriptions as sources for interdisciplinary research. Proceedings of the Fourth International Symposium on Runes and Runic Inscriptions in Göttingen, 4-9 August 1995] (in German and English). Göttingen: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110154559.

- Melnikova, Elena Aleksandrovna (2001). Skandinavskie runicheskie nadpisi: novye nakhodki i interpretatsii; teksty, perevod, kommentarii Скандинавские рунические надписи: новые находки и интерпретации; тексты, перевод, комментарии [Scandinavian Runic Inscriptions: New Findings and Interpretations; Texts, Translation, Commentary]. The Earliest Sources on History of Eastern Europe (in Russian). Moscow: "Vostochnaya literatura", Russian Academy of Sciences. ISBN 9785020180826.

- Müllenhoff, Karl Viktor (1865). "Zeugnisse und Excurse zur deutschen Heldensage" [Testimonies and Excursions to the German Heroic Tale]. Deutsches Alterthum (in German). Berlin: Weidmannsche Buchhandlung. 12. Retrieved 2023-04-10.

- Nosov, E. N. (1987). Taavitsainen, J.-P. (ed.). "New Data on the Ryurik Gorodishche near Novgorod" (PDF). Fennoscandia Archaeologica. Ekenäs: Archaeological Society of Finland (IV). ISSN 0781-7126.

- Nosov, Evgueny Nikolaevich (1998). "Pervye skandinavy v Severnoy Rusi" Первые скандинавы в Северной Руси [The first Scandinavians in Northern Rus']. In Hedman, Anders; Kirpichnikov, Anatoly (eds.). Vikingi i slavyane. Uchyonye, politiki, diplomaty o russko-skandinavskikh otnosheniyakh Викинги и Славяне. Ученые, политики, дипломаты о русско-скандинавских отношениях [Vikings and Slavs. Scientists, Politicians, Diplomats on Russian-Scandinavian Relations] (in Russian and English). St. Petersburg: Dmitry Bulanin. ISBN 9785860070950.

- Orel, Vladimir (2003). A Handbook of Germanic Etymology. Leiden, Boston: Brill. ISBN 9789004128750.

- "Örvar-Odds Saga" (in Icelandic).

- Petersen, Niels Matthias, ed. (1847). Hervarar saga ok Heiðreks konungs. Nordiske oldskrifter (in Icelandic and Danish). Vol. 3. Translated by Thorarensen, Gísli. Copenhagen: Printing House of Brothers Berling. OCLC 162978576.

- Peterson, Gary Dean (2016). Vikings and Goths: A History of Ancient and Medieval Sweden. Jefferson (North Carolina): McFarland. ISBN 9781476624341.

- Price, Neil (2000), "Novgorod, Kiev and their Satellites: The City-State Model and the Viking Age Polities of European Russia", in Hansen, Mogens Herman (ed.), A Comparative Study of Thirty City-state Cultures: An Investigation, Copenhagen: Kgl. Danske Videnskabernes Selskab, pp. 263–275

- Pritsak, Omeljan (1981). The Origin of Rus': Old Scandinavian Sources Other than the Sagas. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-64465-4.

- Rafn, Carl Christian, ed. (1830). "Gaungu-Hrólf Saga". Fornaldar sögur Nordrlanda eptir gömlum handritum (in Icelandic). Kaupmannahöfn: Popp.

- Rafn, Carl Christian (1852). Antiquités Russes d'après les monuments historiques des Islandais et des anciens Scandinaves (in French, Latin, and Icelandic). Copenhague: Frères Berling.

- Rix, Helmut; Kümmel, Martin (2001). LIV, Lexikon der indogermanischen Verben: die Wurzeln und ihre Primärstammbildungen (in German). Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert. ISBN 9783895002199.

- "G 114". Runor (in Swedish and English). Department of Scandinavian Languages, Uppsala University. Retrieved 2023-09-12.

- "N 62". Runor (in Swedish and English). Department of Scandinavian Languages, Uppsala University. Retrieved 2023-09-30.

- "Sö 148". Runor (in Swedish and English). Department of Scandinavian Languages, Uppsala University. Retrieved 2023-09-30.

- "Sö 338". Runor (in Swedish and English). Department of Scandinavian Languages, Uppsala University. Retrieved 2023-09-12.

- "U 209". Runor (in Swedish and English). Department of Scandinavian Languages, Uppsala University. Retrieved 2023-09-12.

- "U 636". Runor (in Swedish and English). Department of Scandinavian Languages, Uppsala University. Retrieved 2023-09-30.

- "Öl 28". Runor (in Swedish and English). Department of Scandinavian Languages, Uppsala University. Retrieved 2023-09-30.

- Schröder, Franz Rolf (1917), "Hálfdanar saga Eysteinssonar", in Gederschiöld, Gustaf; Gering, Hugo; Eugen, Mogk (eds.), Altnordische Saga-Bibliothek (in German), Halle an der Saale: Max Niemeyer

- Skeie, Tore (2021). The Wolf Age: The Vikings, the Anglo-Saxons and the Battle for the North Sea Empire. Translated by McCullough, Alison. Pushkin Press. ISBN 9781782276487.

- Sturluson, Snorri (1225). . Vol. 1. Translated by Laing, Samuel. London: Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans (published 1844) – via Wikisource.

- Sturluson, Snorri (1230). Linder, N.; Haggson, H. A. (eds.). Heimskringla. Saga Ólafs Tryggvasonar (in Icelandic). Vol. 1. Uppsala: W. Schultz (published 1870).

- "Sögubrot af nokkrum fornkonungum í Dana ok Svíaveldi" (in Icelandic).

- "Sörla saga sterka" (in Icelandic).

- Thomsen, Vilhelm (1877). Bondarovski, Paul (ed.). The Relations between Ancient Russia and Scandinavia, and the Origin of the Russian State. Oxford, London: Paul Bondarovski (published 2017).

- Jónsson, Guðni, ed. (1951). "Vilkinus skattgildir Hertnið konung". Þiðreks saga af Bern (in Icelandic). Reykjavík: Íslendingasagnaútgáfan.

- Tikhomirov, Mikhail (1959). Skvirsky, D. (ed.). The Towns of Ancient Rus. Translated by Sdobnikov, Y. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House. LCCN 61037475. OCLC 405762.

- Trubachyov, O. N., ed. (1980). Etimologicheskiy slovar' slavyanskikh yazykov Этимологический словарь славянских языков [Etymological Dictionary of the Slavic Languages] (in Russian). Vol. 7. Moscow: Nauka.

- Vigfússon, Guðbrandur; Unger, Carl Rikard, eds. (1862). "Þáttr Eymundar ok Ólafs konúngs". Flateyjarbók (in Icelandic). Christiania: P. T. Mallings.

- Wachler, Ferdinand (1851). "GARDHARIKI". In Ersch, Johann Samuel; Gruber, Johann Gottfried; Hassel, G.; Müller, Wilhelm; Hoffmann, A. G.; Leskien, August (eds.). Allgemeine Encyclopädie der Wissenschaften und Künste in alphabetischer Folge von genannten Schriftstellern [Universal Encyclopaedia of Sciences and Arts in Alphabetical Order by Authors Named] (in German). Vol. 52. Leipzig: Brockhaus. Retrieved 2023-05-06.

- White, Cecilia (2016). Þjalar-Jóns saga: The Icelandic Text with an English Translation, Introduction and Notes (MSc). University of Iceland.

- Zoëga, Geir T. (1910). A Concise Dictionary of Old Icelandic. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2023-05-06.