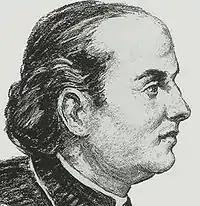

Gaspar del Bufalo

Gaspar Melchior Balthazar del Bufalo, CPPS (January 6, 1786 – December 28, 1837), also known as Gaspare del Bufalo, was a Catholic priest and the founder of the Missionaries of the Precious Blood. Canonised as a saint in 1954, he is liturgically commemorated on October 21.

Gaspar Melchior Balthazar del Bufalo | |

|---|---|

| |

| Priest | |

| Born | January 6, 1786 Rome, Papal States |

| Died | December 28, 1837 Rome, Papal States |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church |

| Beatified | 18 December 1904, Saint Peter's Basilica, Kingdom of Italy by Pope Pius X |

| Canonized | 12 June 1954, Saint Peter's Basilica, Vatican City by Pope Pius XII |

| Feast | January 2 |

| Attributes | Priest's cassock |

Life

Gaspar del Bufalo was born in Rome on the Feast of the Epiphany, January 6, 1786. He was baptized that same day and given the name Gaspar Melchior Balthazar, the traditional names of the magi who visited the child Jesus. The son of Annunziata and Antonio del Bufalo, he grew up in the city of Rome, in the servants' quarters of a noble family, where his father worked as chef.[1]

His father was a failed entrepreneur who had dabbled in the theater and in professional soccer[2] before taking a position as a cook in the household of the Altieri family, whose palace was across from the Church of the Gesù in Rome.

Because of his delicate health, his pious mother had him confirmed at the age of one and a half years. As he was suffering from an incurable malady of the eyes, which threatened to leave him blind, prayers were offered to Francis Xavier for his recovery. Through the influence of his mother he became greatly devoted to Francis Xavier, whose relic is prominently displayed on an altar of the Gesù. In 1787, he was recovered and cherished in later life a special devotion to the Apostle of India, and selected him as the special patron of the congregation which he later founded.[3]

Gaspar was also active in several ministries. He visited the sick and the poor often and founded a young persons’ religious organization whose members prayed and did charitable work together. He was ordained to the Catholic priesthood in the diocese of Rome in 1808.[1] Soon after Gaspar formed an evening society for the laborers and farm workers who came into Rome from the countryside to sell their wares. He provided catechism for orphans and children of the poor and set up a night shelter for the homeless.

Along with other clergy who refused to take the oath of allegiance to Napoleon Bonaparte in 1809 after the deportation of Pope Pius VII, he was sent into exile to northern Italy and imprisoned for four years. Upon his return to Rome in 1814, he considered joining the Jesuits, who had recently been reestablished. However, in view of the needs of the time and at the request of Pius VII, he engaged in the ministry of preaching missions to the people in order to reestablish some order in the midst of the chaos of the time.[1]

Missionaries of the Precious Blood

Despite facing considerable difficulties, in 1815 he founded a society of priests, the Missionaries of the Precious Blood, at the abbey of San Felice in Giano, Umbria.[4] With the help of local people, Gaspar worked to repair the abandoned 10th century monastery.[2]

The year 1821 was a time of great lawlessness in the Papal States and many towns were out of the control of the civil authorities. Bandits controlled many of the towns in the coastal provinces. Cardinal Cristaldi, papal treasurer and advisor to Pope Pius VII, suggested that Gaspar and his new band of missionaries go into the towns and provinces where the bandits lived and establish mission houses. There they were to preach the Word, establish churches and chapels, and see to the continued instruction of the people. Between 1821 and 1823 six new mission houses were opened. Gaspar and his companions went out and preached the merits of the Precious Blood. They called the people to repentance and to return to faithfulness. They would preach on the street corners at night. They instructed the children. Armed with only the crucifix, they went into the hills,[5] where Gaspar negotiated a peace with the banditi.[2]

_-_interior%252C_statue_of_Saint_Gaspar_del_Bufalo.jpg.webp)

Although Gaspar was very popular in his native city, he was not without enemies. His activity in converting the "briganti", who came in crowds and laid their guns at his feet after he had preached to them in their mountain hiding-places, excited the ire of the officials who profited from brigandage through bribes and in other ways. These enemies almost induced Leo XII to suspend del Bufalo.[3]

He also faced ecclesiastical opposition. One major objection to the new society was that its name, The Society of the Precious Blood, was considered unecclesiastical. Gaspar was accused of disregarding canon law and the mission cross and chain that the members wore was completely untraditional. This opposition began under the reign of Pope Pius VII (around 1820) who had been a strong support of the society at its founding in 1815.[4] This opposition became so strong that the successor to Pius VII, Leo XII, was positively adverse to the community. It is noted that this was at a time when Gaspar was being more and more open in his criticism of abuses in the Church and the government of the Papal States. Gaspar felt that this opposition was more of a personal attack on himself and so he offered to step down as moderator of the community so that things could be smoothed over. Fortunately, this was not needed as the situation with Leo XII was resolved after a meeting between the two of them.[5]

His missionary efforts were extremely dramatic. One contemporary, the Passionist priest and bishop Vincent Strambi, described his preaching as being "like a spiritual earthquake." He was also a friend of Vincent Pallotti, founder of the Pallotines, who assisted at Gaspar's deathbed. He is particularly known for his devotion to the Precious Blood of Christ and for spreading this devotion during his lifetime.

Until his death on December 28, 1837, he worked tirelessly to re-evangelize central Italy, especially the Papal States. He was well known for his eloquence in preaching, his devotion to the poor (especially the Santa Galla Hospice in Rome), and his work with the brigands of southern Lazio.

In 1836, his strength began to fail. He had given his last mission in Rome at the Chiesa Nuova in 1837. Although fatally ill, he hastened to Rome, where the cholera was raging, to administer to the spiritual wants of the plague-stricken. He returned to Albano but went again to Rome at the suggestion of Cardinal Franzoni, the cardinal protector of the Congregation, in December 1837. It proved too much for him, and he succumbed in the midst of his labours on December 28, 1837.[3]

His funeral was held in Rome at the church of Sant'Angelo in Pescheria, near the Teatro di Marcello, and he was buried in Albano. Later, his body was transferred to the house of the Missionaries on the Via dei Crociferi in Rome (Santa Maria in Trivio), where it remains today.

The titles accorded to him by his contemporaries:"II Santo", "Apostle of Rome", "Il martello dei Carbonari" (Hammer of Italian Freemasonry).[3]

Veneration

Gaspar del Bufalo was beatified by Pope Pius X on August 29, 1904.[4][6] The cause for his canonization was opened on July 12, 1949,[6] and he was canonized by Pope Pius XII on June 12, 1954. Originally commemorated on December 29, his feast was moved in 1962 to October 21.[7] His feast is celebrated in the City of Rome and by members of the Missionaries of the Precious Blood on October 21.[1]

Legacy

He had a significant influence on Maria De Mattias, foundress of the Adorers of the Blood of Christ (A.S.C.),[8] although it was Venerable Giovanni Merlini C.PP.S. who was most directly associated with St. Maria in establishing her congregation.

See also

References

- ""St. Gaspar del Bufalo", Precious Blood Parish Missions". Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2013-03-08.

- "St. Gaspar del Bufalo:A Saint in Motion", Cincinnati Province of the Missionaries of the Precious Blood Archived 2011-10-13 at the Wayback Machine

- Müller, Ulrich. "St. Gaspare del Bufalo." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 6. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1909. 7 Mar. 2013

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "Our Founder Saint Gaspar del Bufalo", Missionaries of the Precious Blood

- "St. Gaspar: Founder of the Society of the Precious Blood". Archived from the original on 2012-11-20. Retrieved 2013-03-08.

- Index ac status causarum beatificationis servorum dei et canonizationis beatorum (in Latin). Typis polyglottis vaticanis. January 1953. p. 84.

- Butler, Alban, and Burns, Paul. Butler's Lives of the Saints United Kingdom, Burns & Oates, 1995, p. 223

- "St. Gaspare del Bufalo", Adorers of the Blood of Christ Archived 2013-03-10 at the Wayback Machine

Sources

- Attwater, Donald and Catherine Rachel John. "The Penguin Dictionary of Saints," 3rd edition, New York: Penguin Books, 1993. ISBN 0-14-051312-4.