Gastropod-borne parasitic disease

Gastropod-borne parasitic diseases (GPDs) are a group of infectious diseases that require a gastropod species to serve as an intermediate host for a parasitic organism (typically a nematode or trematode) that can infect humans upon ingesting the parasite or coming into contact with contaminated water sources.[1] These diseases can cause a range of symptoms, from mild discomfort to severe, life-threatening conditions, with them being prevalent in many parts of the world, particularly in developing regions. Preventive measures such as proper sanitation and hygiene practices, avoiding contact with infected gastropods and cooking or boiling food properly can help to reduce the risk of these diseases.

| Gastropod-borne Parasitic Disease | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Gastropod-borne Helminthiasis; Gastropod-borne Helminthic Disease |

| |

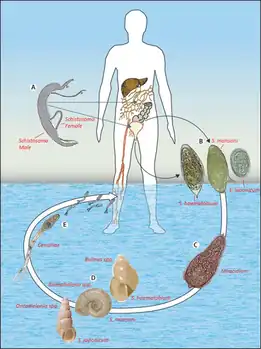

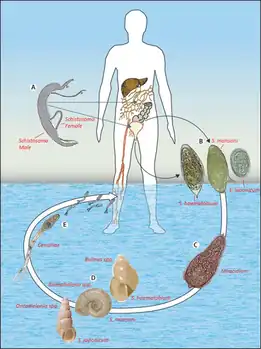

| Example of a gastropod-borne parasitic disease – The transmission cycle of schistosomiasis | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Abdominal pain, bloating, cough, chest pain, cognitive impairment, diarrhea, difficulty breathing, fever, headache, jaundice, liver fibrosis, nausea, neck stiffness, organ damage, rash, vomiting and weight loss. |

| Causes | Nematode or trematode parasites |

| Risk factors | Exposure to unsafe, contaminated water and food sources. |

| Prevention | Controlling and eliminating the intermediate snails host; implementing improved sanitation and hygiene; properly washing and cooking of freshwater vegetables, gastropods, crustaceans and amphibians. |

| Treatment | Anthelmintic drugs: albendazole, mebendazole, oxamniquine, praziquantel and triclabendazole |

| Deaths | 20,000–200,000 per year |

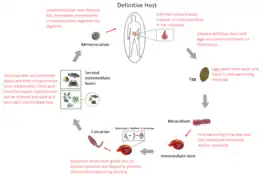

Gastropod-borne parasitic diseases affects over 300 million people worldwide[2] and makes up several of the Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) listed by the World Health Organisation.[3] They are a significant public health concern in developing countries and are caused by various nematode and trematode species that use gastropods as their intermediate hosts. Gastropods are known to host several helminthic parasites due to their ability to thrive in different ecosystems.[4] Gastropod-borne parasitic diseases have a significant impact on human, livestock and companion animal health. Over 140 gastropod species from 20 families are known intermediate hosts for nematode and trematode species that affect hundreds of millions of people in around 90 countries.[1] Moreover, its estimated over 18,000 digenean trematode species and approximately 50 metastrongyloid nematode species use gastropods as their intermediate hosts and are of medical or veterinary importance.[5] Gastropod-borne parasitic diseases are a significant public health problem in endemic areas and can lead to chronic malnutrition and other long-term health problems. Control measures such as health education campaigns, improved sanitation and hygiene practices and better food safety measures can help to reduce the prevalence of gastropod-borne parasitic diseases.

Trematodes

Trematodes (commonly known as flukes) are a subclass of the Trematoda and are obligatory internal parasites.[6] The Digenea consist of around 80 families and 6,000 described species, with only a dozen species known to actively infect humans.[6] The most well-known and predominate gastropod-borne parasitic disease is schistosomiasis, while other less known GPDs include Amphistomiasis, Brachylaimiasis, Clinostomiasis, Clonorchiasis, Dicrocoeliasis, Echinostomiasis, Eurytrematosis, Fasciolopsiasis, Fascioliasis, Haplorchiasis, Heterophyiasis, Metagonimiasis, Metorchiasis, Nanophyetiasis, Neodiplostomiasis, Opisthorchiasis, Paragonimiasis and Philophthalmiasis (commonly grouped as foodborne trematodiasis). Theses trematode diseases cause significant morbidity and mortality in humans, especially in developing countries and have a significant impact on livestock and companion animal health.[7] Both schistosomiasis and foodborne trematodiases are significant public health problem in endemic areas and are identified as a Neglected tropical diseases by the World Health Organisation (WHO).[3]

Amphistomiasis

Amphistomiasis (also known as paramphistomiasis) is a parasitic infection caused by several genera of intestinal flukes that belong to the superfamily Paramphistomoidea (Calicophoron, Carmyerius, Cotylophoron, Explanatum, Gastrodiscoides, Gigantocotyle, Paramphistomum and Watsonius).[8] These parasites commonly infect the digestive tract of ruminants (such as cattle, sheep, and goats), with species like Gastrodiscoides hominis and. Watsonius watsoni infecting humans. Amphistomiasis is primarily found in Asia, Guyana, Zambia, Nigeria and Russia in areas where people have close contact with infected livestock.[9] The transmission of amphistomiasis is associated with the ingestion of undercooked (or raw) freshwater plants contaminated with the metacercarial stage of the parasite. However, other organisms like fish and freshwater invertebrates can also contain these metacercaria. The larvae then migrate to the rumen or abomasum of the host animal, where they attach themselves to the mucosa and feed on blood. The trematode then infects the intestinal wall of the host, leading to chronic inflammation and damage. Symptoms of amphistomiasis can include abdominal pain, diarrhea, vomiting, fatigue, and weight loss. In severe cases, the infection can lead to intestinal obstruction, liver damage, and other complications. Amphistomiasis is typically diagnosed through the identification of eggs or adult trematodes in fecal samples or through endoscopic examination of the intestines. Treatment usually involves anthelmintic medications such as praziquantel, to kill the adult worms and prevent further damage to the intestinal wall.

Brachylaimiasis

Brachylaimiasis is a parasitic infection caused by the intestinal trematode genus, Brachylaima, which infects various animals and one species (B. cribbi) known to infect humans.[10] The life cycle of Brachylaima involves a two (or more) intermediate terrestrial gastropod host being infected through the ingestion of eggs excreted by an infected definitive host. After ingestion, it takes one to three months for an asexual sporocyst to be created and start to produce cercariae within the first intermediate gastropod host. These cercariae are secreted through the mucus of the first intermediate gastropod host and seek out to infect other gastropods through skin to skin contact. The first intermediate gastropod host can also act as both the first and second intermediate host, as infected snails shedding cercariae in their mucus can infect themselves, making them a first and second intermediate host simultaneously.[11] The successful cercariae develop into mature metacercariae after four months and can survive up to another four months within the second gastropod host. The transmission cycle is completed when the secondary intermediate gastropod host is ingested by a bird, mammal, or reptile definitive host and the metacercariae reaches the intestines.[12]

Of the species of Brachylaima investigated, only B. cribbi has been found to cause infection within humans, with the only cases been described in Australia.[13] The symptoms of brachylaimiasis in humans include abdominal pain, diarrhea, vomiting, fever, anemia and eosinophilia. The infection is usually mild or self-limiting, but can be chronic and severe in rare cases. Brachylaimiasis is usually treated with the anthelminthic drug, praziquantel, which is effective against most trematode infections. The prevention of brachylaimiasis involves avoiding the consumption of undercooked (or raw) snails and slugs or unwashed vegetables (such as lettuce or spinach) contaminated with the slime/faeces/corpses of a second intermediate gastropod host.[13]

Clinostomiasis

Clinostomiasis is a parasitic infection caused by the esophageal trematode species, Clinostomum complanatum.

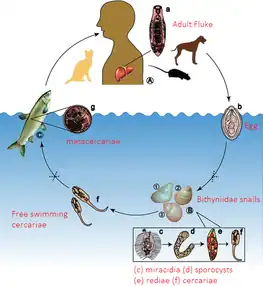

Clonorchiasis

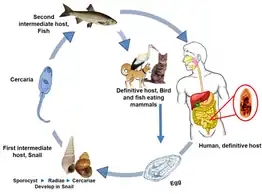

Clonorchiasis is a parasitic infection caused by the Chinese liver fluke, Clonorchis sinensis.[14] The disease is prevalent in East Asia, including China, Korea, Vietnam and parts of Russia. The transmission of clonorchiasis occurs through the ingestion of raw or undercooked fish that are infected with the larvae of Clonorchis sinensis. Once inside the human body, the larvae develop into adult flukes in the bile ducts of the liver. The adult flukes can cause inflammation and blockage of the bile ducts, which can lead to liver damage and other complications.

Symptoms of clonorchiasis may not appear immediately after infection but can manifest as early as a few days or up to several months later. The most common symptoms include abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, fever and jaundice. In some cases, the infection may be asymptomatic and individuals may not show any signs of the disease. Diagnosis of clonorchiasis is made through a combination of medical history, physical examination and laboratory tests. Imaging tests such as ultrasound, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may also be used to detect the presence of the liver fluke in the bile ducts. The treatment of clonorchiasis involves the use of anthelmintic medications, such as praziquantel or albendazole to kill the adult flukes. However, if the infection has caused significant damage to the liver, additional medical treatment may be necessary. The prevention of clonorchiasis involves properly cooking or freezing caught fish as it can kill the larvae inside and prevent infection.

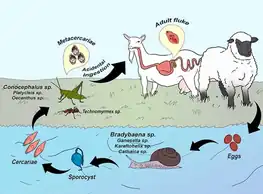

Dicrocoeliasis

Dicrocoeliasis is a parasitic infection caused by the liver fluke genus, Dicrocoelium

Echinostomiasis

Echinostomiasis is a parasitic infection caused by several species of intestinal fluke from the family, Echinostomatidae. The most common cause of echinostomiasis is from the members of the genus, Echinostoma.[15] These parasites are found worldwide, but are particularly common in South East Asia such as South Korea and the Philippines. The infection is usually acquired via the consumption of undercooked (or raw) freshwater fish, amphibians, mollusks or crustaceans contaminated with infective metacercaria. Symptoms of echinostomiasis can include abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting and weight loss. In some cases, the infection can lead to more severe complications such as intestinal obstruction or inflammation. Echinostomiasis is diagnosed by examining stool samples for the presence of adult worms or eggs. Treatment typically involves the use of anthelmintic medications such as praziquantel or albendazole. Prevention involves avoiding the consumption of raw or undercooked meat.

Eurytrematosis

Eurytrematosis is a parasitic infection caused by the pancreatic trematode genus, Eurytrema.[16] This trematode genus primarily affects ruminants such as cattle and sheep, but has been known to infect humans as well.[17] The transmission cycle of eurytrematosis starts with eggs being excreted by an infected definitive host and being ingested by a terrestrial gastropod host. After ingestion, the eggs hatch and after several months, asexual sporocyst are created and start to produce cercariae, that are expelled into the environment by the first intermediate gastropod host. These cercariae are secreted through the mucus of the first intermediate gastropod host and are ingested by the second intermediate hosts, which is an insect species such as a grasshopper (Orthoptera) or an ant. The successful cercariae develop into mature metacercariae and wait for months within the second intermediate insect host. The transmission cycle is then completed when the second intermediate host is accidentally ingested by a ruminant, where the adult parasites are then able to reside in the bile ducts of the liver and the pancreatic ducts. In humans, accidental infection can occur through the consumption of contaminated water or food.

The symptoms of Eurytrematosis in ruminants include weight loss, diarrhea and anemia. Infected animals may also exhibit signs of liver damage such as jaundice and ascites. In humans, symptoms can include abdominal pain, diarrhea and weight loss. However, many infected individuals may be asymptomatic. Eurytrematosis is diagnosed through fecal examination for the presence of trematode eggs. Treatment typically involves the use of anthelmintic drugs such as praziquantel, which can effectively kill the adult parasites. However, it is important to note that the use of these drugs in ruminants can result in the release of large numbers of dead parasites, which can cause blockages in the bile ducts and pancreatic ducts, leading to severe complications. The prevention of Eurytrematosis involves proper hygiene and sanitation measures, as well as the control of snail and ant populations in areas where ruminants graze. In addition, proper cooking and handling of food can also help to reduce the risk of human infection. While Eurytrematosis is not a major public health concern in humans, it can have significant economic impacts on the livestock industry due to reduced productivity and increased mortality in infected animals. As such, control and prevention measures are important for the health and well-being of both animals and humans.

Fascioliasis

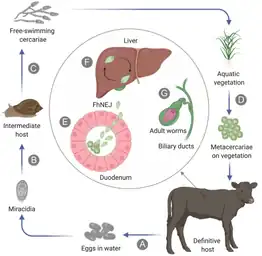

Fascioliasis is a parasitic infection caused by the trematode species, Fasciola hepatica and Fasciola gigantica.[18] It primarily affects domestic and wild animals, but humans can also become infected by consuming contaminated water or vegetables. The transmission of fascioliasis occurs through the ingestion of metacercariae, the infective form of the parasite, which are present on the surface of contaminated plants or in contaminated water. Once inside the human body, the metacercariae migrate to the liver, where they develop into adult flukes. The adult flukes can cause inflammation and damage to the liver, leading to various symptoms.

Symptoms of fascioliasis may vary from mild to severe, depending on the extent of the infection, common symptoms include abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, fever and jaundice. In some cases, the infection may be asymptomatic and individuals may not show any signs of the disease. The diagnosis of fascioliasis is made through a combination of medical history, physical examination and laboratory tests such as ultrasound can detect the presence of the adult flukes in the liver. The treatment of fascioliasis involves the use of anthelmintic medications (such as triclabendazole) to kill the adult flukes. In addition, supportive care, such as rehydration and nutritional support, may be necessary for individuals with severe symptoms. The prevention of fascioliasis involves avoiding the consumption of contaminated water or vegetables, especially in endemic areas and the proper cooking or boiling of vegetables can kill the metacercariae and prevent infection.

Fasciolopsiasis

Fasciolopsiasis is a parasitic infection caused by the giant intestinal fluke, Fasciolopsis buski.[19] It primarily affects humans and pigs in Southeast Asia, the Indian subcontinent and parts of Africa. The transmission of fasciolopsiasis occurs through the ingestion of freshwater plants contaminated with metacercariae, the infective form of Fasciolopsis buski. Once inside the human body, the metacercariae migrate to the small intestine, where they develop into adult flukes. The adult flukes can cause inflammation and damage to the intestinal wall, leading to various symptoms.

Symptoms of fasciolopsiasis may vary from mild to severe, depending on the extent of the infection. Common symptoms include abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, bloating and weight loss. In some cases, the infection may be asymptomatic and individuals may not show any signs of the disease. Diagnosis of fasciolopsiasis is made through a combination of medical history, physical examination and laboratory tests such as ultrasound can be used to detect the presence of the adult flukes in the intestines. The treatment of fasciolopsiasis involves the use of anthelmintic medications, such as praziquantel or albendazole, to kill the adult flukes. In addition, supportive care, such as rehydration and nutritional support, may be necessary for individuals with severe symptoms. The prevention of fasciolopsiasis involves avoiding the consumption of raw or undercooked freshwater plants, such as water chestnuts, watercress and bamboo shoots, especially in endemic areas and the proper cooking or boiling of freshwater plants can kill the metacercariae and prevent infection.

Haplorchiasis

Haplorchiasis is a parasitic infection caused by the intestinal trematode genus, Haplorchis.

Heterophyiasis

Heterophyiasis is a parasitic infection caused by the minute intestinal fluke, Heterophyes heterophyes.

Metagonimiasis

Metagonimiasis is a parasitic infection caused by the intestinal trematode species, Metagonimus yokogawai.[20] The disease affects both humans (and animals) and is primarily found in regions where people consume raw or undercooked freshwater fish such as in East Asia, Siberia, Manchuria, the Balkan states, Israel and Spain. Metagonimiasis is caused by the ingestion of infected raw or undercooked freshwater fish such as trout, salmon, or chub. The trematode then infects the small intestine of the host, leading to chronic inflammation and damage. Symptoms of metagonimiasis can include abdominal pain, diarrhea, vomiting, fever, and weight loss. In severe cases, the infection can lead to intestinal obstruction, liver damage, and other complications. Metagonimiasis is typically diagnosed through the identification of eggs or adult trematodes in fecal samples or through endoscopic examination of the intestines. Treatment usually involves anthelmintic medications such as praziquantel, to kill the adult worms and prevent further damage to the intestinal wall.

Metorchiasis

Metorchiasis is a parasitic infection caused by the liver fluke genus, Metorchis.

Nanophyetiasis

Nanophyetiasis is a parasitic infection caused by the intestinal trematode species, Nanophyetus salmincola.

Neodiplostomiasis

Neodiplostomiasis is a parasitic infection caused by the intestinal trematode species, Neodiplostomum seoulensis.

Opisthorchiasis

Opisthorchiasis is a parasitic infection caused by the liver fluke species, Opisthorchis viverrini and Opisthorchis felineus.[21] It primarily affects humans and other mammals that consume raw or undercooked fish infected with Opisthorchis. The transmission of opisthorchiasis occurs through the ingestion of metacercariae, the infective form of the parasite, which are present in freshwater fish, such as cyprinids and catfish. Once inside the human body, the metacercariae migrate to the bile ducts, where they develop into adult flukes. The adult flukes can cause inflammation and damage to the bile ducts and liver, leading to various symptoms.

Symptoms of opisthorchiasis may vary from mild to severe, depending on the extent of the infection. Common symptoms include abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, bloating and jaundice. In some cases, the infection may be asymptomatic and individuals may not show any signs of the disease. The diagnosis of opisthorchiasis is made through a combination of medical history, physical examination and laboratory tests such as imaging tests (ultrasound) can be used to detect the presence of the adult flukes in the bile ducts and liver. The treatment of opisthorchiasis involves the use of anthelmintic medications, such as praziquantel or albendazole, to kill the adult flukes. In addition, supportive care, such as rehydration and nutritional support, may be necessary for individuals with severe symptoms. The prevention of opisthorchiasis involves avoiding the consumption of raw or undercooked freshwater fish, especially in endemic areas, the proper cooking or boiling of fish can kill the metacercariae and prevent infection.

Paragonimiasis

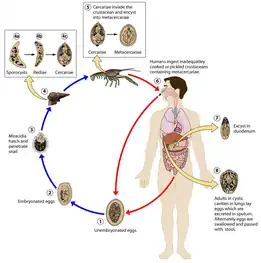

Paragonimiasis is a parasitic infection caused by the lung fluke genus, Paragonimus. It primarily affects humans (and other mammals) that consume raw or undercooked freshwater crabs, crayfish or snails infected with the parasite.[22] The transmission of paragonimiasis occurs through the ingestion of metacercariae, the infective form of the parasite. Once inside the human body, the metacercariae migrate to the lungs, where they develop into adult flukes.

The adult flukes can cause inflammation and damage to the lung tissue, leading to various symptoms. The symptoms of paragonimiasis may vary from mild to severe, depending on the extent of the infection, common symptoms include cough, chest pain, fever, difficulty breathing and coughing up blood. In some cases, the infection may be asymptomatic and individuals may not show any signs of the disease. The diagnosis of paragonimiasis is made through a combination of medical history, physical examination and laboratory tests such as imaging tests (X-ray or CT scan) can be used to detect the presence of the adult flukes in the lungs. The treatment of paragonimiasis involves the use of anthelmintic medications, such as praziquantel or triclabendazole, to kill the adult flukes. In addition, supportive care, such as rehydration and nutritional support, may be necessary for individuals with severe symptoms. The prevention of paragonimiasis involves avoiding the consumption of raw or undercooked freshwater crustaceans or snails, especially in endemic areas. Proper cooking or boiling of these animals can kill the metacercariae and prevent infection. In addition, proper sanitation and hygiene practices, such as washing hands and food properly, can reduce the risk of infection.

Philophthalmiasis

Philophthalmiasis is a parasitic infection caused by the ocular trematode genus, Philophthalmus.

Schistosomiasis

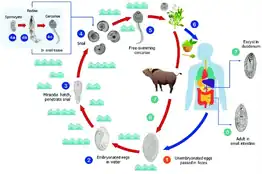

Schistosomiasis (also known as bilharzia) is a parasitic infection caused by several species of the trematode genus, Schistosoma.[23] It primarily affects humans who come into contact with contaminated freshwater sources, such as rivers, lakes, or irrigation canals, where the parasite's intermediate host, freshwater snails (Biomphalaria, Bulinus, Oncomelania), reside. The transmission of schistosomiasis occurs through the penetration of the skin by cercariae, the free-swimming infective form of the parasite, which are released by infected freshwater snails. Once inside the human body, the cercariae migrate to the blood vessels and develop into adult worms, which live in the veins surrounding the bladder and intestines.

The adult worms can cause inflammation, damage to the organs and various symptoms. The symptoms of schistosomiasis may vary depending on the extent of the infection, the species of the parasite and the host's immune response. The acute phase of the infection may present with fever, rash, abdominal pain and diarrhea. The chronic phase of the disease may lead to organ damage, such as liver fibrosis, bladder wall thickening and impaired cognitive function. The diagnosis of schistosomiasis is made through a combination of medical history, physical examination and laboratory tests, including serological tests, stool or urine examination and imaging tests such as ultrasound or X-ray. The treatment of schistosomiasis involves the use of anthelmintic medications, such as praziquantel or oxamniquine, to kill the adult worms. In addition, supportive care, such as rehydration and nutritional support, may be necessary for individuals with severe symptoms. The prevention of schistosomiasis involves avoiding contact with contaminated freshwater sources, such as swimming, wading, or bathing in stagnant water, especially in endemic areas. Proper sanitation and hygiene practices, such as washing hands and clothes properly, can reduce the risk of infection. In addition, control measures, such as snail control programs, health education campaigns and improved water supply and sanitation systems, can help to reduce the prevalence of the disease.

Schistosomiasis is a significant public health problem in many countries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, where it is endemic. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO) over 240 million people worldwide are infected with schistosomiasis and it is responsible for over 20–200,000 deaths annually.[24]

Nematodes

Nematodes have evolved various types of symbiotic relationships with gastropods, with some species have phoretic, parasitic, paratenic, or pathogenic relationships with their gastropod hosts.[25] Relationships with gastropods have evolved independently multiple times, primarily in two groups of nematodes: those who use gastropods as their intermediate host and those who use gastropods as their definitive host.[25] Among the 61 nematode species that use gastropods as their intermediate host, 49 of them belong to the order Strongylida. Similarly, of the 47 nematode species that use gastropods as their definitive host, 33 belong to the order Rhabditida. Notable examples of metastrongyloid species include the rat lungworm, Angiostrongylus (An.) cantonensis, a zoonotic parasite that infects rats and humans. Similarly, metastrongyloid species are common parasites of companion animals such as Angiostrongylus vasorum (or Crenosoma vulpis) infect dogs[26] and Aelurostrongylus abstrusus infects cats.[27]

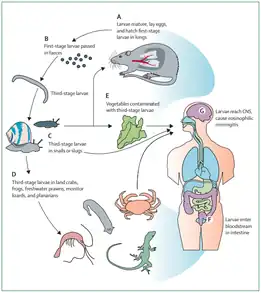

Angiostrongyliasis

Angiostrongyliasis, is a parasitic infection caused in humans by the nematode, Angiostrongylus cantonensis.[29] Angiostrongyliasis is transmitted through the ingestion of the third-stage (L3), infective larva of the parasite. Human angiostrongyliasis is transmitted to people who consume raw or undercooked freshwater snails (or slugs), crustacea, amphibians, planarians, reptiles or unwashed vegetables (such as lettuce or spinach) contaminated with the slime/faeces/corpses of infected invertebrates. Once inside the human body, the third stage larvae migrates to the central nervous system, where they can cause inflammation, damage to the brain tissue and various neurological symptoms.

The symptoms of angiostrongyliasis vary depending on the extent of the infection, the species of the parasite and the host's immune response, with common symptoms including headache, neck stiffness, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain and fever. In severe cases, the infection can lead to meningitis, encephalitis, coma and death. The diagnosis of angiostrongyliasis is made through a combination of medical history, physical examination and laboratory tests, including serological tests, stool examination and imaging tests such as a MRI or CT scan. The treatment of angiostrongyliasis involves the use of supportive care and anthelmintic medications, such as albendazole or mebendazole, to kill the adult worms. In severe cases, hospitalisation and intensive care may be necessary to manage the complications of the infection. The prevention of angiostrongyliasis involves avoiding contact with/consuming infected invertebrate hosts (especially in endemic areas) and the proper cooking/boiling/cleaning of any crustacea/mollusks/vegetables will help prevent infection.

Angiostrongyliasis is a rare but potentially life-threatening disease that is endemic in many countries, particularly in Southeast Asia, the Pacific Islands and the Caribbean. The incidence of the disease has been increasing in recent years and it has been reported in non-endemic areas such as the United States and Europe. Control measures, such as health education campaigns, improved sanitation and hygiene practices and better food safety measures can help to reduce the prevalence of the disease.

References

- Lu, Xiao-Ting; Gu, Qiu-Yun; Limpanont, Yanin; Song, Lan-Gui; Wu, Zhong-Dao; Okanurak, Kamolnetr; Lv, Zhi-Yue (2018-04-09). "Snail-borne parasitic diseases: an update on global epidemiological distribution, transmission interruption and control methods". Infectious Diseases of Poverty. 7 (1): 28. doi:10.1186/s40249-018-0414-7. ISSN 2049-9957. PMC 5890347. PMID 29628017.

- Camejo, Ana (March 2016). "Control Issues". Trends in Parasitology. 32 (3): 169–171. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2016.01.005. ISSN 1471-4922. PMID 26826785.

- "Neglected tropical diseases – GLOBAL". www.who.int. Retrieved 2023-04-06.

- Adema, Coen M.; Bayne, Christopher J.; Bridger, Joanna M.; Knight, Matty; Loker, Eric S.; Yoshino, Timothy P.; Zhang, Si-Ming (2012-12-27). "Will All Scientists Working on Snails and the Diseases They Transmit Please Stand Up?". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 6 (12): e1835. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001835. ISSN 1935-2735. PMC 3531516. PMID 23301104.

- Giannelli, Alessio; Cantacessi, Cinzia; Colella, Vito; Dantas-Torres, Filipe; Otranto, Domenico (March 2016). "Gastropod-Borne Helminths: A Look at the Snail–Parasite Interplay". Trends in Parasitology. 32 (3): 255–264. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2015.12.002. ISSN 1471-4922. PMID 26740470.

- Olson, P.D.; Cribb, T.H.; Tkach, V.V.; Bray, R.A.; Littlewood, D.T.J. (July 2003). "Phylogeny and classification of the Digenea (Platyhelminthes: Trematoda)11Nucleotide sequence data reported in this paper are available in the GenBank™, EMBL and DDBJ databases under the accession numbers AY222082–AY222285". International Journal for Parasitology. 33 (7): 733–755. doi:10.1016/s0020-7519(03)00049-3. ISSN 0020-7519. PMID 12814653.

- CRIBB, T; BRAY, R; OLSON, P; TIMOTHY, D; LITTLEWOOD, J (2003), "Life Cycle Evolution in the Digenea: a New Perspective from Phylogeny", Advances in Parasitology Volume 54, Advances in Parasitology, Elsevier, vol. 54, pp. 197–254, doi:10.1016/s0065-308x(03)54004-0, ISBN 978-0-12-031754-7, PMID 14711086, retrieved 2023-04-06

- Tandon, Veena; Roy, Bishnupada; Shylla, Jollin Andrea; Ghatani, Sudeep (2019), Toledo, Rafael; Fried, Bernard (eds.), "Amphistomes", Digenetic Trematodes, Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, Cham: Springer International Publishing, vol. 1154, pp. 255–277, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-18616-6_9, ISBN 978-3-030-18615-9, PMID 31297765, S2CID 239126929, retrieved 2023-04-30

- Sah, Ranjit; Acosta, Lucrecia; Toledo, Rafael (August 2019). "A case report of human gastrodiscoidiasis in Nepal". Parasitology International. 71: 56–58. doi:10.1016/j.parint.2019.03.014. ISSN 1383-5769. PMID 30926537. S2CID 88475287.

- Gracenea, Mercedes; Gállego, Laia (October 2017). "Brachylaimiasis:Brachylaimaspp. (Digenea: Brachylaimidae) Metacercariae Parasitizing the Edible SnailCornu aspersum(Helicidae) in Spanish Public Marketplaces and Health-Associated Risk Factors". Journal of Parasitology. 103 (5): 440–450. doi:10.1645/17-29. ISSN 0022-3395. PMID 28650216. S2CID 1984428.

- Butcher, A.R.; Grove, D.I. (March 2005). "Second intermediate host land snails and definitive host animals ofBrachylaima cribbiin southern Australia". Parasite. 12 (1): 31–37. doi:10.1051/parasite/2005121031. ISSN 1252-607X. PMID 15828579.

- Butcher, A.R.; Grove, D.I. (June 2003). "Field prevalence and laboratory susceptibility of southern Australian land snails toBrachylaima cribbisporocyst infection". Parasite. 10 (2): 119–125. doi:10.1051/parasite/2003102119. ISSN 1252-607X. PMID 12847918.

- Butcher, A.R.; Grove, D.I. (2001-07-01). "Description of the life-cycle stages of Brachylaima cribbi n. sp. (Digenea: Brachylaimidae) derived from eggs recovered from human faeces in Australia". Systematic Parasitology. 49 (3): 211–221. doi:10.1023/A:1010616920412. ISSN 1573-5192. PMID 11466482. S2CID 12302617.

- Tang, Ze-Li; Huang, Yan; Yu, Xin-Bing (2016-07-06). "Current status and perspectives of Clonorchis sinensis and clonorchiasis: epidemiology, pathogenesis, omics, prevention and control". Infectious Diseases of Poverty. 5 (1): 71. doi:10.1186/s40249-016-0166-1. ISSN 2049-9957. PMC 4933995. PMID 27384714.

- "CDC – DPDx – Echinostomiasis". www.cdc.gov. 2019-06-25. Retrieved 2023-04-30.

- Sousa, Davi Emanuel Ribeiro de; Castro, Márcio Botelho de (2022-11-01). "Pancreatic eurytrematosis in small ruminants: A forgotten disease or an untold history?". Veterinary Parasitology. 311: 109794. doi:10.1016/j.vetpar.2022.109794. ISSN 0304-4017. PMID 36087515.

- Schwertz, Claiton Ismael (2015). "Eurytrematosis: An emerging and neglected disease in South Brazil". World Journal of Experimental Medicine. 5 (3): 160–163. doi:10.5493/wjem.v5.i3.160. ISSN 2220-315X. PMC 4543810. PMID 26309817.

- González-Miguel, Javier; Becerro-Recio, David; Siles-Lucas, Mar (2021-01-01). "Insights into Fasciola hepatica Juveniles: Crossing the Fasciolosis Rubicon". Trends in Parasitology. 37 (1): 35–47. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2020.09.007. ISSN 1471-4922. PMID 33067132.

- Ridha, Muhammad Rasyid; Indriyati, Liestiana; Andiarsa, Dicky; Wardhana, April Hari (2021). "A review of Fasciolopsis buski distribution and control in Indonesia". Veterinary World. 14 (10): 2757–2763. doi:10.14202/vetworld.2021.2757-2763. PMC 8654757. PMID 34903937. Retrieved 2023-04-17.

- Mahanta, Jagadish (2022), "Metagonimiasis", Textbook of Parasitic Zoonoses, Microbial Zoonoses, Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore, pp. 309–316, doi:10.1007/978-981-16-7204-0_29, ISBN 978-981-16-7203-3, retrieved 2023-04-25

- Simakova, Anastasia V.; Poltoratskaya, Natalya V.; Babkina, Irina B.; Poltoratskaya, Tatyana N.; Shikhin, Alexander V.; Pankina, Tatyana M. (2022-02-16), Bacha, Umar (ed.), "The World Largest Focus of the Opisthorchiasis in the Ob-Irtysh Basin, Russia, Caused by Opisthorchis felineus", Rural Health, IntechOpen, doi:10.5772/intechopen.91634, ISBN 978-1-83969-370-0, retrieved 2023-04-17

- Diaz, James H. (July 2013). "Paragonimiasis acquired in the United States: native and nonnative species". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 26 (3): 493–504. doi:10.1128/CMR.00103-12. ISSN 1098-6618. PMC 3719489. PMID 23824370.

- Colley, Daniel G.; Bustinduy, Amaya L.; Secor, W. Evan; King, Charles H. (2014-06-28). "Human schistosomiasis". Lancet. 383 (9936): 2253–2264. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61949-2. ISSN 1474-547X. PMC 4672382. PMID 24698483.

- "Schistosomiasis". www.who.int. Retrieved 2023-04-17.

- Grewal, P. S.; Grewal, S. K.; Tan, L.; Adams, B. J. (June 2003). "Parasitism of molluscs by nematodes: types of associations and evolutionary trends". Journal of Nematology. 35 (2): 146–156. ISSN 0022-300X. PMC 2620629. PMID 19265989.

- Andrus, P. S.; Rae, R.; Wade, C. M. (2022). "Nematodes and trematodes associated with terrestrial gastropods in Nottingham, England". Journal of Helminthology. 96: e81. doi:10.1017/s0022149x22000645. ISSN 0022-149X. PMID 36321434. S2CID 253247002.

- Penagos-Tabares, Felipe; Lange, Malin K.; Chaparro-Gutiérrez, Jenny J.; Taubert, Anja; Hermosilla, Carlos (2018-03-27). "Angiostrongylus vasorum and Aelurostrongylus abstrusus: Neglected and underestimated parasites in South America". Parasites & Vectors. 11 (1): 208. doi:10.1186/s13071-018-2765-0. ISSN 1756-3305. PMC 5870519. PMID 29587811.

- Wang, Qiao-Ping; Lai, De-Hua; Zhu, Xing-Quan; Chen, Xiao-Guang; Lun, Zhao-Rong (2008-10-01). "Human angiostrongyliasis". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 8 (10): 621–630. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70229-9. ISSN 1473-3099. PMID 18922484.

- Nguyen, Yann; Rossi, Benjamin; Argy, Nicolas; Baker, Catherine; Nickel, Beatrice; Marti, Hanspeter; Zarrouk, Virginie; Houzé, Sandrine; Fantin, Bruno; Lefort, Agnès (June 2017). "Autochthonous Case of Eosinophilic Meningitis Caused by Angiostrongylus cantonensis, France, 2016". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 23 (6): 1045–1046. doi:10.3201/eid2306.161999. ISSN 1080-6059. PMC 5443449. PMID 28518042.