Walls of Constantinople

The Walls of Constantinople (Greek: Τείχη της Κωνσταντινουπόλεως) are a series of defensive stone walls that have surrounded and protected the city of Constantinople (today Istanbul in Turkey) since its founding as the new capital of the Roman Empire by Constantine the Great. With numerous additions and modifications during their history, they were the last great fortification system of antiquity, and one of the most complex and elaborate systems ever built.

| Walls of Constantinople | |

|---|---|

| Istanbul, Turkey | |

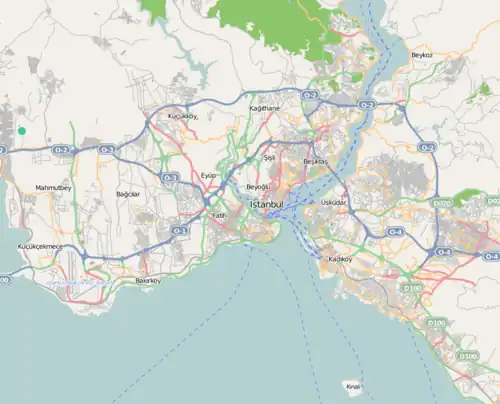

Map showing Constantinople and its walls during the Byzantine era | |

Walls of Constantinople | |

| Coordinates | 41.0122°N 28.9760°E |

| Type | Walls |

| Height | Up to 12 m |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Turkey |

| Controlled by | Roman Empire, Byzantine Empire, Latin Empire, Ottoman Empire |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Land walls partly ruined, sea walls largely torn down; Restoration work underway by the Istanbul Municipality. |

| Site history | |

| Built | 4th–5th centuries, with later restorations and additions |

| Built by | Septimius Severus, Constantine I, Constantius II, Theodosius II, Justinian I, Heraclius, Leo V, Theophilos, Manuel I Komnenos |

| Materials | Limestone, brick |

| Battles/wars | Avar-Persian siege of 626, First and Second Arab sieges, Revolt of Thomas the Slav, Fourth Crusade, Second and final Ottoman siege |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iii, iv |

| Designated | 1985 (9th session) |

| Part of | Historic Areas of Istanbul |

| Reference no. | 356 |

| Region | Europe and North America |

Initially built by Constantine the Great, the walls surrounded the new city on all sides, protecting it against attack from both sea and land. As the city grew, the famous double line of the Theodosian Walls was built in the 5th century. Although the other sections of the walls were less elaborate, they were, when well-manned, almost impregnable for any medieval besieger. They saved the city, and the Byzantine Empire with it, during sieges by the Avar-Sassanian coalition, Arabs, Rus', and Bulgars, among others. The advent of gunpowder siege cannons rendered the fortifications vulnerable, but cannon technology was not sufficiently advanced to capture the city on its own, and the walls could be repaired between reloading. Ultimately, the city fell from the sheer weight of numbers of the Ottoman forces on 29 May 1453 after a two-month siege.

The walls were largely maintained intact during most of the Ottoman period until sections began to be dismantled in the 19th century, as the city outgrew its medieval boundaries. Despite lack of maintenance, many parts of the walls survived and are still standing today. A large-scale restoration program has been underway since the 1980's.

Land Walls

Walls of Greek and Roman Byzantium

| Part of a series on the |

| Byzantine army |

|---|

|

| Structural history |

|

|

| Campaign history |

| Lists of wars, revolts and civil wars, and battles |

| Strategy and tactics |

|

According to tradition, the city was founded as Byzantium by Greek colonists from Megara, led by the eponymous Byzas, around 658 BC.[1] The city then consisted of a small region around an acropolis located on the easternmost hill (corresponding to the modern site of the Topkapı Palace). According to the late Byzantine Patria of Constantinople, ancient Byzantium was enclosed by a small wall that began on the northern edge of the acropolis, extended west to the Tower of Eugenios, then went south and west towards the Strategion and the Baths of Achilles, continued south to the area known in Byzantine times as Chalkoprateia, and then turned, in the area of the Hagia Sophia, in a loop towards the northeast, crossed the regions known as Topoi and Arcadianae and reached the sea at the later quarter of Mangana. This wall was protected by 27 towers and had at least two landward gates, one which survived to become known as the Arch of Urbicius, and one where the Milion monument was later located. On the seaward side, the wall was much lower.[2] Although the author of the Patria asserts that this wall dated to the time of Byzas, the French researcher Raymond Janin thinks it more likely that it reflects the situation after the city was rebuilt by the Spartan general Pausanias, who conquered the city in 479 BC. This wall is known to have been repaired, using tombstones, under the leadership of a certain Leo in 340 BC, against an attack by Philip II of Macedon.[3]

Byzantium was relatively unimportant during the early Roman period. Contemporaries described it as wealthy, well peopled and well fortified, but that affluence came to an end because the city supported Pescennius Niger (r. 193–194) in his war against Septimius Severus (r. 193–211). According to the account of Cassius Dio (Roman History, 75.10–14), the city held out against Severan forces for three years, until 196, with its inhabitants resorting even to throwing bronze statues at the besiegers when they ran out of other projectiles.[4] Severus punished the city harshly: the strong walls were demolished, and the town was deprived of its civic status, being reduced to a mere village dependent on Heraclea Perinthus.[5] However, appreciating the city's strategic importance, Severus eventually rebuilt it and endowed it with many monuments, including a Hippodrome and the Baths of Zeuxippus, as well as a new set of walls, located some 300–400 m to the west of the old ones. Little is known of the Severan Wall save for a short description of its course by Zosimus (New History, II.30.2–4) and that its main gate was located at the end of a porticoed avenue (the first part of the later Mese) and shortly before the entrance of the later Forum of Constantine. The wall seems to have extended from near the modern Galata Bridge in the Eminönü quarter south through the vicinity of the Nuruosmaniye Mosque to curve around the southern wall of the Hippodrome, and then going northeast to meet the old walls near the Bosporus.[6] The Patria also mention the existence of another wall during the siege of Byzantium by Constantine the Great (r. 306–337) during the latter's conflict with Licinius (r. 308–324), in 324. The text mentions that a fore-wall (proteichisma) ran near the Philadephion, located at about the middle of the later, Constantinian city, suggesting the expansion of the city beyond the Severan Wall by this time.[7]

Constantinian Walls

Like Severus before him, Constantine began to punish the city for siding with his defeated rival, but he too soon realised the advantages of Byzantium's location. From 324 to 336, the city was thoroughly rebuilt and inaugurated on 11 May 330 under the name of "New Rome" or "Second Rome". Eventually, the city would most commonly be referred to as Constantinople, the "City of Constantine", in dedication to its founder (Gk. Κωνσταντινούπολις, Konstantinoupolis).[8] New Rome was protected by a new wall about 2.8 km (15 stadia) west of the Severan wall.[9] Constantine's fortification consisted of a single wall, reinforced with towers at regular distances, which began to be constructed in 324 and was completed under his son Constantius II (r. 337–361).[10][11] Only the approximate course of the wall is known: it began at the Church of St. Anthony at the Golden Horn, near the modern Atatürk Bridge, ran southwest and then southwards, passed east of the great open cisterns of Mocius and of Aspar, and ended near the Church of the Theotokos of the Rhabdos on the Propontis coast, somewhere between the later sea gates of St. Aemilianus and Psamathos.[12]

Already by the early 5th century, Constantinople had expanded outside the Constantinian Wall in the extramural area known as the Exokionion or Exakionion.[13] The wall survived during much of the Byzantine period, even though it was replaced by the Theodosian Walls as the city's primary defense. An ambiguous passage refers to extensive damage to the city's "inner wall" from an earthquake on 25 September 478, which likely refers to the Constantinian wall. When repairs were being undertaken, to prevent an invasion by Atilla, the Blues and Greens, the supporters of chariot-racing teams, supplied 16,000 men between them for the building effort.[14]

Theophanes the Confessor reports renewed earthquake damage in 557.[15] It appears that large parts survived relatively intact until the 9th century: the 11th-century historian Kedrenos records that the "wall at Exokionion", likely a portion of the Constantinian wall, collapsed in an earthquake in 867.[16] Only traces of the wall appear to have survived in later ages, although Van Millingen states that some parts survived in the region of the İsakapı until the early 19th century.[17] The recent construction of Yenikapı Transfer Center has unearthed a section of the foundation of the wall of Constantine.[18]

Gates

The names of a number of gates of the Constantinian Wall survive, but scholars debate their identity and exact location.

The Old Golden Gate (Latin: Porta Aurea, Ancient Greek: Χρυσεία Πύλη), known also as the Xerolophos Gate and the Gate of Saturninus,[19] is mentioned in the Notitia Urbis Constantinopolitanae, which further states that the city wall itself in the region around it was "ornately decorated". The gate stood somewhere on the southern slopes of the Seventh Hill.[20] Its construction is often attributed to Constantine, but is in fact of uncertain age. It survived until the 14th century, when the Byzantine scholar Manuel Chrysoloras described it as being built of "wide marble blocks with a lofty opening", and crowned by a kind of stoa.[21] In late Byzantine times, a painting of the Crucifixion was allegedly placed on the gate, leading to its later Ottoman name, İsakapı ("Gate of Jesus"). It was destroyed by an earthquake in 1509, but its approximate location is known through the presence of the nearby İsakapı Mescidi mosque.[21][22]

The identity and location of the Gate of At[t]alos (Πόρτα Ἀτ[τ]άλου, Porta At[t]alou) are unclear. Cyril Mango identifies it with the Old Golden Gate;[21] van Millingen places it on the Seventh Hill, at a height probably corresponding to one of the later gates of the Theodosian Wall in that area;[20] and Raymond Janin places it further north, across the Lycus and near the point where the river passed under the wall.[19] In earlier centuries, it was decorated with many statues, including one of Constantine, which fell down in an earthquake in 740.[19][23]

The only gate whose location is known with certainty, aside from the Old Golden Gate, is the Gate of Saint Aemilianus (Πόρτα τοῦ ἁγίου Αἰμιλιανοῦ, Porta tou hagiou Aimilianou), named in Turkish Davutpaşa Kapısı. It lay at the juncture with the sea walls, and served the communication with the coast. According to the Chronicon Paschale, the Church of St Mary of Rhabdos, where the rod of Moses was kept, stood next to the gate.[19][24]

The Old Gate of the Prodromos (Παλαιὰ Πόρτα τοῦ Προδρόμου, Palaia Porta tou Prodromou), named after the nearby Church of St John the Baptist (called Prodromos, "the Forerunner", in Greek), is another unclear case. Van Millingen identifies it with the Old Golden Gate,[25] while Janin considers it to have been located on the northern slope of the Seventh Hill.[19]

The last known gate is the Gate of Melantias (Πόρτα τῆς Μελαντιάδος, Porta tēs Melantiados), whose location is also debated. Van Millingen considered it to be a gate of the Theodosian Wall (the Pege Gate),[26] while more recently, Janin and Mango have rebutted this, suggesting that it was located on the Constantinian Wall. While Mango identifies it with the Gate of the Prodromos,[27] Janin considers the name to have been a corruption of the ta Meltiadou quarter, and places the gate to the west of the Mocius cistern.[19] Other authors identified it with the Gate of Adrianople (A. M. Schneider) or with the Gate of Rhesios (A. J. Mordtmann).[28]

Theodosian Walls

The double Theodosian Walls (Greek: τεῖχος Θεοδοσιακόν, teichos Theodosiakon), located about 2 km (1.2 miles) to the west of the old Constantinian Wall, were erected during the reign of Emperor Theodosius II (r. 402–450), after whom they were named. The work was carried out in two phases, with the first phase erected during Theodosius' minority under the direction of Anthemius, the praetorian prefect of the East, and was finished in 413 according to a law in the Codex Theodosianus. An inscription discovered in 1993 however records that the work lasted for nine years, indicating that construction had already begun ca. 404/405, in the reign of Emperor Arcadius (r. 383–408). This initial construction consisted of a single curtain wall with towers, which now forms the inner circuit of the Theodosian Walls.[29]

Both the Constantinian and the original Theodosian walls were severely damaged in two earthquakes, on 25 September 437 and 6 November 447.[30] The latter was especially powerful and destroyed large parts of the wall, including 57 towers. Subsequent earthquakes, including another major one in January 448, compounded the damage.[31] Theodosius II ordered the praetorian prefect Constantine to supervise the repairs, made all the more urgent as the city was threatened by the presence of Attila the Hun in the Balkans. Employing the city's chariot-racing factions in the work, the walls were restored in a record 60 days, according to the Byzantine chroniclers and three inscriptions found in situ.[32] It is at this date that the majority of scholars believe the second, outer wall to have been added, as well as a wide moat opened in front of the walls, but the validity of that interpretation is questionable; the outer wall was possibly an integral part of the original fortification concept.[32]

Throughout their history, the walls were damaged by earthquakes and floods of the Lycus river. Repairs were undertaken on numerous occasions, as testified by the numerous inscriptions commemorating the emperors or their servants who undertook to restore them. The responsibility for these repairs rested on an official variously known as the Domestic of the Walls or the Count of the Walls (Δομέστικος/Κόμης τῶν τειχέων, Domestikos/Komēs tōn teicheōn), who employed the services of the city's populace in this task.[11][33] After the Latin conquest of 1204, the walls fell increasingly into disrepair, and the revived post-1261 Byzantine state lacked the resources to maintain them, except in times of direct threat.[34]

Course and topography

In their present state, the Theodosian Walls stretch for about 5.7 km (3.5 mi) from south to north, from the "Marble Tower" (Turkish: Mermer Kule), also known as the "Tower of Basil and Constantine" (Gk. Pyrgos Basileiou kai Kōnstantinou) on the Propontis coast to the area of the Palace of the Porphyrogenitus (Tr. Tekfur Sarayı) in the Blachernae quarter. The outer wall and the moat terminate even earlier, at the height of the Gate of Adrianople. The section between the Blachernae and the Golden Horn does not survive since the line of the walls was later brought forward to cover the suburb of Blachernae, and its original course is impossible to ascertain, as it lies buried beneath the modern city.[11][35]

From the Sea of Marmara, the wall turns sharply to the northeast until it reaches the Golden Gate, at about 14& m above sea level. From there and until the Gate of Rhegion the wall follows a more or less straight line to the north, climbing the city's Seventh Hill. From there the wall turns sharply to the northeast, climbing up to the Gate of St. Romanus, located near the peak of the Seventh Hill at some 68 m above sea level.[36] From there the wall descends into the valley of the river Lycus, where it reaches its lowest point at 35 m above sea level. Climbing the slope of the Sixth Hill, the wall then rises up to the Gate of Charisius or Gate of Adrianople, at some 76 m height.[36] From the Gate of Adrianople to the Blachernae, the walls fall to a level of some 60 m. From there the later walls of Blachernae project sharply to the west, reaching the coastal plain at the Golden Horn near the so-called Prisons of Anemas.[36]

Construction

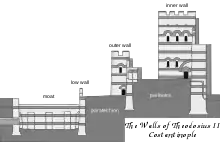

The Theodosian Walls consist of the main inner wall (μέγα τεῖχος, mega teichos, "great wall"), separated from the lower outer wall (ἔξω τεῖχος, exō teichos or μικρὸν τεῖχος, mikron teichos, "small wall") by a terrace, the peribolos (περίβολος).[37] Between the outer wall and the moat (σοῦδα, souda) there stretched an outer terrace, the parateichion (τὸ ἔξω παρατείχιον), while a low breastwork crowned the moat's eastern escarpment. Access to both terraces was possible through posterns on the sides of the walls' towers.[38]

The inner wall is a solid structure, 4.5–6 m thick and 12 m high. It is faced with carefully cut limestone blocks, while its core is filled with mortar made of lime and crushed bricks. Between seven and eleven bands of brick, approximately 40 cm thick, traverse the structure, not only as a form of decoration, but also strengthening the cohesion of the structure by bonding the stone façade with the mortar core, and increasing endurance to earthquakes.[39] The wall was strengthened with 96 towers, mainly square but also a few octagonal ones, three hexagonal and a single pentagonal one. They were 15–20 m tall and 10–12 m wide, and placed at irregular distances, according to the rise of the terrain: the intervals vary between 21 and 77 m, although most curtain wall sections measure between 40 and 60 meters.[40] Each tower had a battlemented terrace on the top. Its interior was usually divided by a floor into two chambers, which did not communicate with each other. The lower chamber, which opened through the main wall to the city, was used for storage, while the upper one could be entered from the wall's walkway, and had windows for view and for firing projectiles. Access to the wall was provided by large ramps along their side.[41] The lower floor could also be accessed from the peribolos by small posterns. Generally speaking, most of the surviving towers of the main wall have been rebuilt in Byzantine or Ottoman times, and only the foundations of some are of original Theodosian construction. Furthermore, while until the Komnenian period, the reconstructions largely remained true to the original model, later modifications ignored the windows and embrasures on the upper story and focused on the tower terrace as the sole fighting platform.[42]

The outer wall was 2 m thick at its base, and featured arched chambers on the level of the peribolos, crowned with a battlemented walkway, reaching a height of 8.5–9 m.[43] Access to the outer wall from the city was provided either through the main gates or through small posterns on the base of the inner wall's towers. The outer wall likewise had towers, situated approximately midway between the inner wall's towers, and acting in supporting role to them.[41] They are spaced at 48–78 m, with an average distance of 50–66 m.[44] Only 62 of the outer wall's towers survive. With few exceptions, they are square or crescent-shaped, 12–14 m tall and 4 m wide.[45] They featured a room with windows on the level of the peribolos, crowned by a battlemented terrace, while their lower portions were either solid or featured small posterns, which allowed access to the outer terrace.[43] The outer wall was a formidable defensive edifice in its own right: in the sieges of 1422 and 1453, the Byzantines and their allies, being too few to hold both lines of wall, concentrated on the defence of the outer wall.[46]

The moat was situated at a distance of about 20 m from the outer wall. The moat itself was over 20 m wide and as much as 10 m deep, featuring a 1.5 m tall crenellated wall on the inner side, serving as a first line of defence.[43][47] Transverse walls cross the moat, tapering towards the top so as not to be used as bridges. Some of them have been shown to contain pipes carrying water into the city from the hill country to the city's north and west. Their role has therefore been interpreted as that of aqueducts for filling the moat and as dams dividing it into compartments and allowing the water to be retained over the course of the walls. According to Alexander van Millingen, there is little direct evidence in the accounts of the city's sieges to suggest that the moat was ever actually flooded.[48] In the sections north of the Gate of St. Romanus, the steepness of the slopes of the Lycus valley made the construction maintenance of the moat problematic; it is probable therefore that the moat ended at the Gate of St. Romanus, and did not resume until after the Gate of Adrianople.[49]

The weakest section of the wall was the so-called Mesoteichion (Μεσοτείχιον, "Middle Wall"). Modern scholars are not in agreement over the extent of that portion of the wall, which has been variously defined from as narrowly as the stretch between the Gate of St. Romanus and the Fifth Military Gate (A.M. Schneider) to as broad as from the Gate of Rhegion to the Fifth Military Gate (B. Tsangadas) or from the Gate of St. Romanus to the Gate of Adrianople (A. van Millingen).[50]

The walls survived the entire Ottoman period and appeared in travelogues of foreign visitors to Constantinople/Istanbul. A 16th-century Chinese geographical treatises, for example, recorded, "Its city has two walls. A sovereign prince lives in the city...".[51]

Gates

The wall contained nine main gates, which pierced both the inner and the outer walls, and a number of smaller posterns. The exact identification of several gates is debatable for a number of reasons. The Byzantine chroniclers provide more names than the number of the gates, the original Greek names fell mostly out of use during the Ottoman period, and literary and archaeological sources provide often contradictory information. Only three gates, the Golden Gate, the Gate of Rhegion and the Gate of Charisius, can be established directly from the literary evidence.[52]

In the traditional nomenclature, established by Philipp Anton Dethier in 1873, the gates are distinguished into the "Public Gates" and the "Military Gates", which alternated over the course of the walls. According to Dethier's theory, the former were given names and were open to civilian traffic, leading across the moat on bridges, and the latter were known by numbers, were restricted to military use and led only to the outer sections of the walls.[53] Today that division is, if retained at all, only a historiographical convention. There is sufficient reason to believe that several of the "Military Gates" were also used by civilian traffic. In addition, a number of them have proper names, and the established sequence of numbering them, based on their perceived correspondence with the names of certain city quarters lying between the Constantinian and Theodosian Walls, which have numerical origins, has been shown to be erroneous. For instance, the Deuteron, the "Second" Quarter, was located not in the southwest behind the Gate of the Deuteron or "Second Military Gate", as would be expected, but in the northwestern part of the city.[54]

First Military Gate

The gate is a small postern, which lies at the first tower of the land walls, at the junction with the sea wall. It features a wreathed Chi-Rhō Christogram above it.[55] It was known in late Ottoman times as the Tabak Kapı.

Golden Gate

Following the walls from south to north, the Golden Gate (Greek: Χρυσεία Πύλη, Chryseia Pylē; Latin: Porta Aurea; Turkish: Altınkapı or Yaldızlıkapı), is the first gate to be encountered. It was the main ceremonial entrance into the capital, used especially for the occasions of a triumphal entry of an emperor into the capital on the occasion of military victories or other state occasions such as coronations.[56][57] On rare occasions, as a mark of honor, the entry through the gate was allowed to non-imperial visitors: papal legates (in 519 and 868) and, in 710, to Pope Constantine. The Gate was used for triumphal entries until the Komnenian period; thereafter, the only such occasion was the entry of Michael VIII Palaiologos into the city on 15 August 1261, after its reconquest from the Latins.[58] With the progressive decline in Byzantium's military fortunes, the gates were walled up and reduced in size in the later Palaiologan period, and the complex converted into a citadel and refuge.[59][60]

The Golden Gate was emulated elsewhere, with several cities naming their principal entrance thus, for instance Thessaloniki (also known as the Vardar Gate) or Antioch (the Gate of Daphne),[61] as well as the Kievan Rus', who built monumental "Golden Gates" at Kiev and Vladimir. The entrance to San Francisco Bay, California, was similarly named the Golden Gate in the mid-19th century, in a distant historical tribute to Byzantium.

The date of the Golden Gateate's construction is uncertain, with scholars divided between Theodosius I and Theodosius II. Earlier scholars favored the former, but the current majority view tends to the latter, meaning that the gate was constructed as an integral part of the Theodosian Walls.[62] The debate has been carried over to a now-lost Latin inscription in metal letters that stood above the doors and commemorated their gilding in celebration of the defeat of an unnamed usurper:[63]

Haec loca Theudosius decorat post fata tyranni.

aurea saecla gerit qui portam construit auro.

(English translation)

Theodosius adorned these places after the downfall of the tyrant.

He brought a golden age who built the gate from gold.

While the legend has not been reported by any known Byzantine author, an investigation of the surviving holes wherein the metal letters were riveted verified its accuracy. It also showed that the first line stood on the western face of the arch, while the second on the eastern.[64] According to the current view, this refers to the usurper Joannes (r. 423–425),[56] while according to the supporters of the traditional view, it indicates the gate's construction as a free-standing triumphal arch in 388–391 to commemorate the defeat of the usurper Magnus Maximus (r. 383–388) and was only later incorporated into the Theodosian Walls.[59][63][65]

The gate, built of large square blocks of polished white marble fitted together without cement, has the form of a triumphal arch with three arched gates, the middle one larger than the two others. The gate is flanked by large square towers, which form the 9th and 10th towers of the inner Theodosian wall.[56][66] With the exception of the central portal, the gate remained open to everyday traffic.[67] The structure was richly decorated with numerous statues, including a statue of Theodosius I on an elephant-drawn quadriga on top, echoing the Porta Triumphalis of Rome, which survived until it fell down in the 740 Constantinople earthquake.[59][68] Other sculptures were a large cross, which fell in an earthquake in 561 or 562; a Victory, which was cast down in the reign of Michael III; and a crowned Fortune of the city.[57][66] In 965, Nikephoros II Phokas installed the captured bronze city gates of Mopsuestia in the place of the original ones.[69]

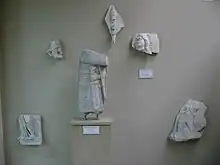

The main gate itself was covered by an outer wall, pierced by a single gate, which in later centuries was flanked by an ensemble of reused marble reliefs.[61] According to descriptions of Pierre Gilles and English travelers from the 17th century, these reliefs were arranged in two tiers, and featured mythological scenes, including the Labours of Hercules. These reliefs, lost since the 17th century with the exception of some fragments now in the Istanbul Archaeological Museum, were probably put in place in the 9th or 10th centuries to form the appearance of a triumphal gate.[70][71] According to other descriptions, the outer gate was also topped by a statue of Victory, holding a crown.[72]

Despite its ceremonial role, the Golden Gate was one of the strongest positions along the walls of the city and withstood several attacks during the various sieges. With the addition of transverse walls on the peribolos between the inner and outer walls, it formed a virtually separate fortress.[73] Its military value was recognized by John VI Kantakouzenos (r. 1347–1354), who records that it was virtually impregnable, capable of holding provisions for three years and defying the whole city if need be. He repaired the marble towers and garrisoned the fort, but had to surrender it to John V Palaiologos (r. 1341–1391) when he abdicated in 1354.[74][75] John V undid Kantakouzenos' repairs and left it unguarded, but in 1389–90 he too rebuilt and expanded the fortress, erecting two towers behind the gate and extending a wall some 350 m to the sea walls, thus forming a separate fortified enceinte inside the city to serve as a final refuge.[76][77] In the event, John V was soon after forced to flee there from a coup led by his grandson, John VII. The fort held out successfully in the subsequent siege that lasted several months, and in which cannons were possibly employed.[78] In 1391 John V was compelled to raze the fort by Sultan Bayezid I (r. 1389–1402), who otherwise threatened to blind his son Manuel, whom he held captive.[76][79] Emperor John VIII Palaiologos (r. 1425–1448) attempted to rebuild it in 1434, but was thwarted by Sultan Murad II.

According to one of the many Greek legends about the Constantinople's fall to the Ottomans, when the Turks entered the city, an angel rescued the emperor Constantine XI Palaiologos, turned him into marble and placed him in a cave under the earth near the Golden Gate, where he waits to be brought to life again to conquer the city back for Christians. The legend explained the later walling up of the gate as a Turkish precaution against this prophecy.[80]

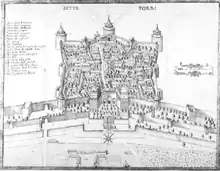

Yedikule Fortress

After his conquest of Constantinople in 1453, Sultan Mehmed II built a new fort in 1458.[81] By adding three larger towers to the four pre-existing ones (towers 8 to 11) on the inner Theodosian wall, he formed the Fortress of the Seven Towers (Turkish: Yedikule Hisarı or Zindanları). It lost its function as a gate, and for much of the Ottoman era, it was used as a treasury, archive, and state prison.[81] It eventually became a museum in 1895.

Xylokerkos Gate

The Xylokerkos or Xerokerkos Gate (Πύλη τοῦ Ξυλοκέρκου/Ξηροκέρκου), now known as the Belgrade Gate (Belgrat Kapısı), lies between towers 22 and 23. Alexander van Millingen identified it with the Second Military Gate, which is located further north.[82] Its name derives from the fact that it led to a wooden circus (amphitheatre) outside the walls.[83] The gate complex is approximately 12 m wide and almost 20 m high, while the gate itself spans 5 m.[84]

According to a story related by Niketas Choniates, in 1189 the gate was walled off by Emperor Isaac II Angelos, because according to a prophecy, it was this gate that Western Emperor Frederick Barbarossa would enter the city through.[85] It was re-opened in 1346,[86] but closed again before the siege of 1453 and remained closed until 1886, leading to its early Ottoman name, Kapalı Kapı ("Closed Gate").[87]

Second Military Gate

The gate (Πύλη τοῦ Δευτέρου) is located between towers 30 and 31, little remains of the original gate, and the modern reconstruction may not be accurate.[88]

Gate of the Spring

_1.jpg.webp)

The Gate of the Spring or Pēgē Gate (Πύλη τῆς Πηγῆς in Greek) was named after a popular monastery outside the Walls, the Zōodochos Pēgē ("Life-giving Spring") in the modern suburb of Balıklı. Its modern Turkish name, Gate of Selymbria (Tr. Silivri Kapısı or Silivrikapı, Gk. Πύλη τῆς Συλημβρίας), appeared in Byzantine sources shortly before 1453.[89] It lies between the heptagonal towers 35 and 36, which were extensively rebuilt in later Byzantine times: its southern tower bears an inscription dated to 1439 commemorating repairs carried out under John VIII Palaiologos. The gate arch was replaced in the Ottoman period. In addition, in 1998 a subterranean basement with 4th/5th century reliefs and tombs was discovered underneath the gate.[90]

Van Millingen identifies this gate with the early Byzantine Gate of Melantias (Πόρτα Μελαντιάδος),[91] but more recent scholars have proposed the identification of the latter with one of the gates of the city's original Constantinian Wall (see above).

It was through this gate that the forces of the Empire of Nicaea, under General Alexios Strategopoulos, entered and retook the city from the Latins on 25 July 1261.[92]

Third Military Gate

The Third Military Gate (Πύλη τοῦ Τρίτου), named after the quarter of the Triton ("the Third") that lies behind it, is situated shortly after the Pege Gate, exactly before the C-shaped section of the walls known as the "Sigma", between towers 39 and 40.[93] It has no Turkish name, and is of middle or late Byzantine construction. The corresponding gate in the outer wall was preserved until the early 20th century, but has since disappeared. It is very likely that this gate is to be identified with the Gate of Kalagros (Πύλη τοῦ Καλάγρου).[94]

Gate of Rhegion

Modern Yeni Mevlevihane Kapısı, located between towers 50 and 51 is commonly referred to as the Gate of Rhegion (Πόρτα Ῥηγίου) in early modern texts, allegedly named after the suburb of Rhegion (modern Küçükçekmece), or as the Gate of Rhousios (Πόρτα τοῦ Ῥουσίου) after the hippodrome faction of the Reds (ῥούσιοι, rhousioi) which was supposed to have taken part in its repair.[95] From Byzantine texts it appears that the correct form is Gate of Rhesios (Πόρτα Ῥησίου), named according to the 10th-century Suda lexicon after an ancient general of Greek Byzantium. A.M. Schneider also identifies it with the Gate of Myriandr[i]on or Polyandrion ("Place of Many Men"), possibly a reference to its proximity to a cemetery. It is the best-preserved of the gates, and retains substantially unaltered from its original, 5th-century appearance.[96]

Fourth Military Gate

The so-called Fourth Military Gate stands between towers 59 and 60, and is currently walled up.[97] Recently, it has been suggested that this gate is actually the Gate of St. Romanus, but the evidence is uncertain.[98]

Gate of St. Romanus

The Gate of St. Romanus (Πόρτα τοῦ Ἁγίου Ρωμάνου) was named so after a nearby church and lies between towers 65 and 66. It is known in Turkish as Topkapı, the "Cannon Gate", after the great Ottoman cannon, the "Basilic", that was placed opposite it during the 1453 siege.[99] With a gatehouse of 26.5 m, it is the second-largest gate after the Golden Gate.[46] According to conventional wisdom, it is here that Constantine XI Palaiologos, the last Byzantine emperor, was killed on 29 May 1453.[100]

This is not the "Topkapı". This website clarifies this: https://istanbulsurlari.ku.edu.tr/en/

Fifth Military Gate

The Fifth Military Gate (Πόρτα τοῦ Πέμπτου) lies immediately to the north of the Lycus stream, between towers 77 and 78, and is named after the quarter of the Pempton ("the Fifth") around the Lycus. It is heavily damaged, with extensive late Byzantine or Ottoman repairs evident.[101][102] It is also identified with the Byzantine Gate of [the Church of] St. Kyriake,[103] and called Sulukulekapı ("Water-Tower Gate") or Hücum Kapısı ("Assault Gate") in Turkish, because there the decisive breakthrough was achieved on the morning of 29 May 1453. In the late 19th century, it appears as the Örülü kapı ("Walled Gate").[102][104]

Some earlier scholars, like J. B. Bury and Kenneth Setton, identify this gate as the "Gate of St. Romanus" mentioned in the texts on the final siege and fall of the city.[105] If this theory is correct, the last Byzantine emperor, Constantine XI, died in the vicinity of this gate during the final assault of 29 May 1453. Support to this theory comes from the fact that the particular gate is located at a far weaker section of the walls than the "Cannon Gate", and the most desperate fighting naturally took place here.

Gate of Charisius

.jpg.webp)

The Gate of Char[i]sius (Χαρ[ι]σίου πύλη/πόρτα), named after the nearby early Byzantine monastery founded by a vir illustris of that name, was, after the Golden Gate, the second-most important gate.[102] In Turkish it is known as Edirnekapı ("Adrianople Gate"), and it is here where Mehmed II made his triumphal entry into the conquered city.[106] This gate stands on top of the sixth hill, which was the highest point of the old city at 77 meters. It has also been suggested as one of the gates to be identified with the Gate of Polyandrion or Myriandrion (Πύλη τοῦ Πολυανδρίου), because it led to a cemetery outside the Walls.[46][107] The last Byzantine emperor, Constantine XI, established his command here in 1453.[108]

Minor gates and posterns

Known posterns are the Yedikule Kapısı, a small postern after the Yedikule Fort (between towers 11 and 12), and the gates between towers 30/31, already walled up in Byzantine times,[87] and 42/43, just north of the "Sigma". On the Yedikule Kapısı, opinions vary as to its origin: some scholars consider it to date already to Byzantine times,[109] while others consider it an Ottoman addition.[110]

Kerkoporta

According to the historian Doukas, on the morning of 29 May 1453, the small postern called Kerkoporta was left open by accident, allowing the first fifty or so Ottoman troops to enter the city. The Ottomans raised their banner atop the Inner Wall and opened fire on the Greek defenders of the peribolos below. This spread panic, beginning the rout of the defenders and leading to the fall of the city.[111] In 1864, the remains of a postern located on the Outer Wall at the end of the Theodosian Walls, between tower 96 and the so-called Palace of the Porphyrogenitus, were discovered and identified with the Kerkoporta by the Greek scholar A.G. Paspates. Later historians, like van Millingen[112] and Steven Runciman[113] have accepted this theory as well. But excavations at the site have uncovered no evidence of a corresponding gate in the Inner Wall (now vanished) in that area, and it may be that Doukas' story is either invention or derived from an earlier legend concerning the Xylokerkos Gate, which several earlier scholars also equated with the Kerkoporta.[114]

Later history

The Theodosian Walls were without a doubt among the most important defensive systems of Late Antiquity. Indeed, in the words of the Cambridge Ancient History, they were "perhaps the most successful and influential city walls ever built – they allowed the city and its emperors to survive and thrive for more than a millennium, against all strategic logic, on the edge of [an] extremely unstable and dangerous world...".[115]

With the advent of siege cannons, such fortifications were becoming obsolete, but their massive size still provided effective defence, as demonstrated during the Second Ottoman Siege in 1422.

Even in the final siege, which led to the fall of the city to the Ottomans three decades later (in 1453), the defenders, severely outnumbered, still managed to repeatedly counter Turkish attempts at undermining the walls, repulse several frontal attacks, and restore the damage from the siege cannons for almost two months. Finally, on 29 May, the decisive attack was launched, and when the Genoese general Giovanni Giustiniani was wounded and withdrew, causing a panic among the defenders, the walls were taken. After the capture of the city, Mehmed had the walls repaired in short order among other massive public works projects, and they were kept in repair during the first centuries of Ottoman rule.

Walls of Blachernae

The Walls of Blachernae connect the Theodosian Walls, which terminate at the height of the Palace of the Porphyrogenitus (Turkish: Tekfur Sarayı), with the sea wall at the Golden Horn. They consist of a series of single walls built in different periods, which cover the suburb of Blachernae.[116] Generally they are about 12–15 meters in height, thicker than the Theodosian Walls and with more closely spaced towers. Situated on a steep slope, they lacked a moat, except on their lower end towards the Golden Horn, where Emperor John VI Kantakouzenos had dug one.[117]

The question of the original fortifications in this area has been examined by several scholars, and several theories have been proposed as to their course.[118] It is known from the Notitia Urbis Constantinopolitanae that the XIV region, which comprised Blachernae, stood apart and was enclosed all around by a wall of its own. Further it is recorded that originally, and at least as late as the Avar-Persian siege of 626, when they were burned down, the important sanctuaries of Panagia Blachernitissa and St. Nicholas lay just outside the quarter's fortifications.[119] Traces of the quarter's walls have been preserved, running from the area of the Porphyrogenitus Palace in straight line to the so-called Prison of Anemas. The original fortified quarter can thereby be roughly traced to have comprised the two northern spurs of the city's Seventh Hill in a triangle, stretching from the Porphyrogenitus Palace to the Anemas Prison, from there to the church of St. Demetrios Kanabos and thence back to the Porphyrogenitus Palace.[120] These fortifications were apparently older than the Theodosian Walls, probably dating to sometime in the 4th century, and were then connected to the new city walls under Theodosius II, with the western wall forming the outer face of the city's defenses and the eastern wall fell into disrepair.[121]

Today, the Theodosian Walls are connected in the vicinity of the Porphyrogenitus Palace with a short wall, which features a postern, probably the postern of the Porphyrogenitus (πυλὶς τοῦ Πορφυρογεννήτου) recorded by John VI Kantakouzenos, and extends from the Palace to the first tower of the so-called Wall of Manuel Komnenos.[122] As recorded by the historian Niketas Choniates, that wall was built by Emperor Manuel I Komnenos (r. 1143–1180) as a protection to the imperial Palace of Blachernae, since the late 11th century the emperors' preferred residence.[123] It is an architecturally excellent fortification, consisting of a series of arches closed on their outer face, built with masonry larger than usual and thicker than the Theodosian Walls, measuring some 5 m at the top.[124] It features eight round and octagonal towers, while the last is square. The wall stretches for 220 m, beginning at an almost right angle from the line of the Theodosian Walls, going westward up to the third tower and then turning sharply north.[124] The quality of the wall's construction was shown in the final Ottoman siege, when repeated attacks, intensive bombardment (including the large bombard of Orban) and attempts at undermining it came to naught.[125] The Komnenian wall lacks a moat, since the difficult terrain of the area makes it unnecessary.[126] The wall features one postern, between the second and third towers, and one large gate, the Eğri Kapı ("Crooked Gate"), between the sixth and seventh towers. Its Turkish name comes from the sharp bend of the road in front of it to pass around a tomb which is supposed to belong to Hazret Hafiz, a companion of Muhammad who died there during the first Arab siege of the city.[127] It is usually, but not conclusively, identified with the Byzantine Kaligaria Gate (πόρτα ἐν τοῖς Καλιγαρίοις, porta en tois Kaligariois), the "Gate of the Bootmakers' Quarter" (cf. Latin caliga, "sandal").[128]

From the last tower of the Wall of Manuel Komnenos to the so-called Prison of Anemas stretches another wall, some 150 m in length, with four square towers. It is probably of later date, and of markedly inferior quality than the Komnenian wall, being less thick and with smaller stones and brick tiles utilized in its construction. It also bears inscriptions commemorating repairs in 1188, 1317 and 1441.[129] A walled-up postern after the second tower is commonly identified with the Gyrolimne Gate (πύλη τῆς Γυρολίμνης, pylē tēs Gyrolimnēs), named after the Argyra Limnē, the "Silver Lake", which stood at the head of the Golden Horn. It probably serviced the Blachernae Palace, as evidenced by its decoration with three imperial busts.[130] Schneider however suggests that the name could refer rather to the Eğri Kapı.[131]

Then comes the outer wall of the Anemas Prison, which connects to a double stretch of walls. The outer wall is known as the Wall of Leo, as it was constructed by Leo V the Armenian (r. 813–820) in 813 to safeguard against the siege by the Bulgarian ruler Krum. This wall was then extended to the south by Michael II (r. 820–829).[132] The wall is a relatively light structure, less than 3 m thick, buttressed by arches which support its parapet and featuring four towers and numerous loopholes.[133] Behind the Leonine Wall lies an inner wall, which was renovated and strengthened by the additions of three particularly fine hexagonal towers by Emperor Theophilos (r. 829–842). The two walls stand some 26 m apart and are pierced by a gate each, together comprising the Gate of Blachernae (πόρτα τῶν Βλαχερνῶν, porta tōn Blachernōn). The two walls form a fortified enclosure, called the Brachionion or Brachiolion ("bracelet") of Blachernae (βραχιόνιον/βραχιόλιον τῶν Βλαχερνῶν) by the Byzantines, and known after the Ottoman capture of the city in Greek as the Pentapyrgion (Πενταπύργιον, "Five Towers"), in allusion to the Yedikule (Gk. Heptapyrgion) fortress.[134] The inner wall is traditionally identified by scholars like van Millingen and Janin with the Wall of Heraclius, built by Emperor Heraclius (r. 610–641) after the Avar-Persian siege to enclose and protect the Church of the Blachernitissa.[135] Schneider identified it in part with the Pteron (Πτερόν, "wing"), built at the time of Theodosius II to cover the northern flank of the Blachernae (hence its alternate designation as proteichisma, "outwork") from the Anemas Prison to the Golden Horn. Consequently, Schneider transferred the identity of the Heraclian Wall on the short stretch of sea wall directly attached to it to its east, which displays a distinct architecture.[136] The identity of the Pteron remains an unresolved question among modern scholars.[137]

Another, short wall was added in later times, probably in the reign of Theophilos, stretching from the junction of the land and sea walls to the sea itself, and pierced by the so-called Wooden Gate (Ξυλίνη πύλη, Xylinē pylē, or Ξυλόπορτα, Xyloporta). Both this wall and the gate were demolished in 1868.[138]

Preservation and restoration work

The land walls run through the heart of modern Istanbul, with a belt of parkland flanking their course. They are pierced at intervals by modern roads leading westwards out of the city. Many sections were restored during the 1980s, with financial support from UNESCO, but the restoration program has been criticized for destroying historical evidence, focusing on superficial restoration, the use of inappropriate materials and poor quality of work. This became apparent in the 1999 earthquakes, when the restored sections collapsed while the original structure underneath remained intact.[139] The threat posed by urban pollution, and the lack of a comprehensive restoration effort, prompted the World Monuments Fund to include them on its 2008 Watch List of the 100 Most Endangered Sites in the world.[140]

Sea walls

The seaward walls (Greek: τείχη παράλια, teichē paralia) enclosed the city on the sides of the Sea of Marmara (Propontis) and the gulf of the Golden Horn (χρυσοῦν κέρας). Although the original city of Byzantium certainly had sea walls, traces of which survive,[141] the exact date for the construction of the medieval walls is a matter of debate. Traditionally, the seaward walls have been attributed by scholars to Constantine I, along with the construction of the main land wall.[142] The first known reference to their construction comes in 439, when the urban prefect Cyrus of Panopolis (in sources often confused with the praetorian prefect Constantine) was ordered to repair the city walls and complete them on the seaward side.[143] This activity is certainly not unconnected to the fact that in the same year, Carthage fell to the Vandals, an event which signaled the emergence of a naval threat in the Mediterranean.[144] This two-phase construction remains the general consensus, but Cyril Mango doubts the existence of any seaward fortifications during Late Antiquity, as they are not specifically mentioned as extant by contemporary sources until much later, around the year 700.[145]

.jpg.webp)

The Sea Walls were architecturally similar to the Theodosian Walls, but of simpler construction. They were formed by a single wall, considerably lower than the land walls, with inner circuits in the locations of the harbours. Enemy access to the walls facing the Golden Horn was prevented by the presence of a heavy chain or boom, installed by Emperor Leo III (r. 717–741), supported by floating barrels and stretching across the mouth of the inlet. One end of this chain was fastened to the Tower of Eugenius, in the modern suburb of Sirkeci, and the other in Galata, to a large, square tower, the Kastellion, the basement of which was later turned into the Yeraltı (Underground) Mosque.[146] At the same time, on the Marmara coast, the city's defence was helped by strong currents, which made an attack by a fleet almost impossible. According to Geoffrey of Villehardouin, that was reason that the Fourth Crusade did not attack the city from that side.[147]

During the early centuries of its existence, Constantinople faced few naval threats. Especially after the wars of Justinian, the Mediterranean had again become a "Roman lake". It was during the first siege of the city by the Avars and the Sasanid Persians that for the first time, a naval engagement was fought off the city itself. After the Arab conquests of Syria and Egypt, a new naval threat emerged. In response, the sea walls were renovated in the early 8th century under Tiberios III (r. 698–705) or Anastasios II (r. 713–715).[148][149] Michael II (r. 820–829) initiated a wide-scale reconstruction, eventually completed by his successor Theophilos (r. 829–842), which increased their height. As these repairs coincided with the capture of Crete by the Saracens, no expense was spared: As Constantine Manasses wrote, "the gold coins of the realm were spent as freely as worthless pebbles".[150] Theophilos' extensive work, essentially rebuilding the sea walls, is testified to by the numerous inscriptions found or otherwise recorded that bear his name, more than those of any other emperor. Despite future changes and restorations, those walls would essentially protect the city until the end of the empire.[151]

During the siege of the city by the Fourth Crusade, the sea walls nonetheless proved to be a weak point in the city's defences, as the Venetians managed to storm them. Following that experience, Michael VIII Palaiologos (r. 1259–1282) took particular care to heighten and strengthen the seaward walls immediately after the Byzantine recapture of the city in 1261 since a Latin attempt to recover the city was regarded as imminent.[152] Furthermore, the installation of the Genoese at Galata across the Golden Horn, agreed upon in the Treaty of Nymphaeum, posed a further potential threat to the city.[153] Time was short, as a Latin attempt to recover the city was expected, and the sea walls were heightened by the addition of 2 m high wooden and hide-covered screens. Ten years later, facing the threat of an invasion by Charles d'Anjou, a second line of walls was built behind the original maritime walls, although no trace of them survives today.[152][154]

The walls were again restored under Andronikos II Palaiologos (r. 1282–1328) and again under his successor Andronikos III Palaiologos (r. 1328–1341), when, on 12 February 1332, a major storm caused breaches in the wall and forced the seaward gates open.[155] In 1351, when the empire was at war with the Genoese, John VI Kantakouzenos again repaired the walls, and even opened a moat in front of the wall facing the Golden Horn. Other repairs are recorded for 1434, again against the Genoese, and again in the years leading up to the final siege and fall of the city to the Ottomans, partly with funds provided by the Despot of Serbia, George Brankovic.[156]

Golden Horn Wall

The wall facing towards the Golden Horn, where in later times most seaborne traffic was conducted, stretched for a total length of 5,600 metres from the cape of St. Demetrius to the Blachernae, where it adjoined the Land Walls. Although most of the wall was demolished in the 1870s, during the construction of the railway line, its course and the position of most gates and towers is known with accuracy. It was built further inland from the shore, and was about 10 metres tall. According to Cristoforo Buondelmonti it featured 14 gates and 110 towers,[157] although 16 gates are known that are of Byzantine origin.[158] The northern shore of the city was always its more cosmopolitan part: a major focal point of commerce, it also contained the quarters allocated to foreigners living in the imperial capital. Muslim traders had their own lodgings (mitaton) there, including a mosque, while from the time of Alexios I Komnenos (r. 1081–1118) on, the emperors granted to the various Italian maritime republics extensive trading quarters which included their own wharfs (skalai) beyond the sea walls.[159]

The known gates of the Golden Horn wall may be traced in order from the Blachernae eastwards to the Seraglio Point, as follows:[146]

The first gate, very near the land walls, was the Koiliomene Gate (Κοιλιωμένη (Κυλιoμένη) Πόρτα, Koiliōmēnē (Kyliomēnē) Porta, "Rolled Gate"), in Turkish Küçük Ayvansaray Kapısı.[160] Shortly after stood the Gate of St. Anastasia (Πύλη τῆς ἁγίας Ἀναστασίας, Pylē tēs hagias Anastasias), located near the Atik Mustafa Pasha Mosque, hence in Turkish Atik Mustafa Paşa Kapısı. In close proximity on the outer side of the walls lay the Church of St. Nicholas Kanabos, which in 1597–1601 served as the cathedral of the Patriarch of Constantinople.[161]

Further down the coast was the gate known in Turkish as Balat Kapı ("Palace Gate"), preceded in close order by three large archways, which served either as gates to the shore or to a harbour that serviced the imperial palace of Blachernae. Two gates are known to have existed in the vicinity in Byzantine times: the Kynegos Gate (Πύλη τοῦ Κυνηγοῦ/τῶν Κυνηγῶν, Pylē tou Kynēgou/tōn Kynēgōn, "Gate of the Hunter(s)"), whence the quarter behind it was named Kynegion, and the Gate of St. John the Forerunner and Baptist (Πόρτα τοῦ ἁγίου Προδρόμου και Βαπτιστοῦ, Porta tou hagiou Prodromou kai Baptistou), though it is not clear whether the latter was distinct from the Kynegos Gate. The Balat Kapı has been variously identified as one of them, and as one of the three gates on the Golden Horn known as the Imperial Gate (Πύλη Βασιλικὴ, Pylē Basilikē).[162][163]

Further south was the Gate of the Phanarion (Πύλη τοῦ Φαναρίου, Pylē tou Phanariou), Turkish Fener Kapısı, named after the local light-tower (phanarion in Greek), which also gave its name to the local suburb.[164] The gate also marked the western entrance of the Petrion Fort (κάστρον τῶν Πετρίων, kastron tōn Petriōn), formed by a double stretch of walls between the Gate of the Phanarion and the Petrion Gate (Πύλη τοῦ Πετρίου, Pylē tou Petriou), in Turkish Petri Kapısı.[165] According to Byzantine tradition, the area was named thus after Peter the Patrician, a leading minister of Justinian I (r. 527–565). A small gate of the western end of the fort's inner wall, near the Phanarion Gate, led to the city, and was called the Gate of Diplophanarion. It was at the Petrion Gate that the Venetians, under the personal leadership of Doge Enrico Dandolo, scaled the walls and entered the city in the 1204 sack. In the 1453 siege an Ottoman attack on the same place was repelled.[166]

The next gate, Yeni Ayakapı ("New Gate of the Saint"), is not Byzantine, unless it replaces an earlier Byzantine entrance.[167] It was constructed by the great Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan in 1582.[168] Shortly after it lies the older Ayakapı ("Gate of the Saint"), known in Greek as the St. Theodosia Gate (Πύλη τῆς Ἁγίας Θεοδοσίας) after the great earby church of St. Theodosia (formerly identified with the Gül Mosque).[167] The next gate is that of Eis Pegas (Πύλη εἰς Πηγάς, Pylē eis Pēgas), known by Latin chroniclers as Porta Puteae or Porta del Pozzo, modern Cibali Kapısı. It was named so because it looked towards the quarter of Pegae (Πηγαὶ, Pēgai, "springs") on the other shore of the Golden Horn.[169] Next was the now-demolished Gate of the Platea (Πόρτα τῆς Πλατέας, Porta tēs Plateas) follows, rendered as Porta della Piazza by Italian chroniclers, and called in Turkish Unkapanı Kapısı ("Gate of the Flour Depot"). It was named after the local quarter of Plate[i]a ("broad place", signifying the broad shoreline at this place).[170] The next gate, Ayazma Kapısı ("Gate of the Holy Well"), is in all probability an Ottoman-era structure.[171]

The next gate is the Gate of the Drungaries (Πύλη τῶν Δρουγγαρίων, Pylē tōn Droungariōn), modern Odunkapısı ("Wood Gate"). Its Byzantine name derives from the high official known as the Drungary of the Watch. It marked the western end of the Venetian quarter.[172] It is followed by the Gate the Forerunner, known as St. John de Cornibus by the Latins, named after a nearby chapel. In Turkish it is known as Zindan Kapısı ("Dungeon Gate").[173] The destroyed Gate of the Perama (Πόρτα τοῦ Περάματος, Porta tou Peramatos) lay in the suburb of Perama ("Crossing"), from which the ferry to Pera (Galata) sailed. It marked the eastern limit of the Venetian quarter of the city, and the beginning of the Amalfitan quarter to its east. In Buondelmonti's map, it is labelled Porta Piscaria, on account of the fishmarket that used to be held there, a name that has been preserved in its modern Turkish appellation, Balıkpazarı Kapısı, "Gate of the Fish-market".[174] This gate is also identified with the Gate of the Jews (Ἑβραϊκὴ Πόρτα, Hebraïkē Porta), Porta Hebraica in Latin sources, although the same name was apparently applied over time to other gates as well.[175] In its vicinity was probably also the Gate of St. Mark, which is recorded in a single Venetian document of 1229. Its identity is unclear, as is the question whether the gate, conspicuously named in honour of the patron saint of Venice, was pre-existing or opened after the fall of the city to the Crusaders in 1204.[176]

To the east of the Perama Gate was the Hikanatissa Gate (Πόρτα τῆς Ἱκανατίσσης, Porta tēs Hikanatissēs), a name perhaps derived from the imperial tagma of the Hikanatoi. The gate marked the eastern end of the Amalfitan quarter of the city and the western edge of the Pisan quarter.[177] Further east lay the Gate of the Neorion (Πόρτα τοῦ Νεωρίου, Porta tou Neōriou), recorded as the Horaia Gate (Πύλη Ὡραία, Pylē Horaia, "Beautiful Gate") in late Byzantine and Ottoman times. As its names testifies, it led to the leading to the Neorion, the main harbour of ancient Byzantium and the oldest naval arsenal of the city.[178] In the early Ottoman period, it was known in Turkish as the Çıfıtkapı ("Hebrew Gate"), but its modern name is Bahçekapı ("Garden Gate"). The eastern limit of the Pisan quarter was located a bit eastwards of the gate.[179]

The 12th-century Genoese quarter of the city extended from there to the east, and in the documents conferring privileges on them one finds mention of two gates: the Porta Bonu ("Gate of Bonus", probably transcribed from Greek Πόρτα Bώνου), and the Porta Veteris Rectoris ("Gate of the old rector"). It is very likely that these two names refer to the same gate, probably named after an otherwise unknown rector Bonus, and located somewhere in the modern Sirkeci district.[180] Finally, the last gate of the Golden Horn wall was the Gate of Eugenius (Πόρτα τοῦ Ἐυγενίου, Porta tou Eugeniou), leading to the Prosphorion harbour. In close proximity was the 4th-century Tower of Eugenius or Kentenarion, where the great chain that closed the entrance to the Golden Horn was kept and suspended from. The gate was also called Marmaroporta (Μαρμαροπόρτα, "Marble Gate"), because it was covered in marble, and featured a statue of the Emperor Julian. It is usually identified with the Ottoman Yalıköşkü Kapısı, and was destroyed in 1871.[181][182]

Propontis Wall

The wall of the Propontis was built almost at the shoreline, with the exception of harbours and quays, and had a height of 12–15 metres, with thirteen gates, and 188 towers.[183][184] and a total length of almost 8,460 metres, with further 1,080 metres comprising the inner wall of the Vlanga harbour. Several sections of the wall were damaged during the construction of the Kennedy Caddesi coastal road in 1956–57.[146] The wall's proximity to the sea and the strong currents of the Propontis meant that eastern and southern shores of the peninsula were comparatively safe from attack, but conversely, the walls had to be protected against the sea itself: a breakwater of boulders was placed in front of their base, and marble shafts were used as bonds in the walls' base to enhance their structural integrity.[183] From the cape at the edge of the ancient acropolis of the city (modern Sarayburnu, Seraglio Point), south and west to the Marble Tower, the Propontis Wall and its gates went as follows:

Marble Tower to Right

Marble Tower to Right Marble Tower from South

Marble Tower from South Marble Tower Connecting structure

Marble Tower Connecting structure Marble Tower Connecting structure

Marble Tower Connecting structure Marble Tower from Kennedy Caddesi

Marble Tower from Kennedy Caddesi

The first gate, now demolished, was the Eastern Gate (Ἑῴα Πύλη, Heōa Pylē) or Gate of St. Barbara (Πύλη τῆς μάρτυρος Βαρβάρας, Pylē tēs martyros Barbaras) after a nearby church, in Turkish Top Kapısı ("Gate of the Cannon"), from which Topkapı Palace takes its name.[185] Unique among the seaward gates, it was, like the Golden Gate, flanked by two large towers of white marble, which in 1816 was used to construct the nearby Marble Kiosk of Sultan Mahmud II. Twice it served as the entry-point for an emperor's triumphal return: in 1126, when John II Komnenos returned from the recapture of his ancestral Kastamonu, and in 1168, when Manuel I Komnenos returned from his victorious campaign against Hungary.[186]

Next was the gate known in Turkish as Değirmen Kapı ("Mill[stone] Gate"), whose Byzantine name is unknown.[186] Close by and to its north stood the great Tower of Mangana, which was intended to hold the one end of the chain, planned (but probably never actually installed) by Manuel I Komnenos to close off the Bosphorus, the other end being at a tower erected on the island of the modern Maiden's Tower (Kız Kulesi) off Chrysopolis (modern Üsküdar), known as Damalis (Δάμαλις) or Arkla (Ἄρκλα) in Byzantine times.[187] The next gate is now known as the Demirkapı ("Iron Gate"), and is an Ottoman-era structure. A Greek name is not known, and it is not known whether a gate stood there in Byzantine times.[188] Behind these two gates extended the quarter of the Mangana (Μάγγανα, "Arsenal"), with its numerous monasteries, the most famous of which were those of St. George of Mangana, the Church of Christ Philanthropos, and of the Theotokos Hodegetria, and the Palace of Mangana.[189] Four small posterns, in two pairs of two, stand at the southern edge of the Mangana quarter, and probably serviced the numerous churches. The names, but not the identity, of two of them have been recorded, the Postern of St. Lazarus (πυλὶς τοῦ ἁγίου Λαζάρου, pylis tou hagiou Lazarou), and the Small Gate of the Hodegetria (μικρὰ πύλη τῆς Ὁδηγητρίας, mikra pylē tēs Hodēgētrias), both named after the respective monasteries located near them.[190] It is also probable that one of them is to be identified with the Postern of Michael the Protovestiarios (παραπυλὶς τοῦ Μιχαὴλ τοῦ πρωτοβεστιαρίου, parapylis tou Michaēl tou prōtovestiariou).[191]

Further south, at the point where the shore turns westwards, are two further gates, the Balıkhane Kapısı ("Gate of the Fish-House") and Ahırkapısı ("Stable Gate"). Their names derive from the buildings inside the Topkapı Palace they led to. Their Byzantine names are unknown.[191] The next gate, on the southeastern corner of the city, was the gate of the imperial Boukoleon Palace, known in Byzantine times as the Gate of the Lion (Gk. Πόρτα Λέοντος, Porta Leontos, in Latin Porta Leonis) after the marble lions that flanked its entrance, as well as Gate of the Bear (πόρτα τῆς ἀρκούδας, porta tēs arkoudas) after depictions of that animal at the quay. In Turkish it is known as Çatladıkapı ("Broken Gate").[192]

To the west of the Bucoleon Palace lies the Church of SS. Sergius and Bacchus, and the first of the harbours of the city's southern shore, that of the Sophiae, named after the wife of Emperor Justin II (r. 565–578) and known originally as the Port of Julian.[193] A small postern is situated in front of the church, while the first larger gate, the Gate of the Sophiae (Πόρτα τῶν Σοφιῶν, Porta tōn Sophiōn) or Iron Gate (Πόρτα Σιδηρᾶ, Porta Sidēra), opened to the harbour. In Turkish, it is known as Kadırgalimanı Kapısı, "Gate of the Harbour of the Galleys".[194] Next was the Gate of Kontoskalion (Πόρτα τοῦ Κοντοσκαλίου), modern Kumkapısı ("Sand Gate"), which opened to the late Byzantine harbour of the same name, intended to replace the long silted-up Harbour of the Sophiae.[195]

The next harbour to the west is the large Harbour of Eleutherius or Theodosius, in the area known as Vlanga. The harbours are now silted up and known as the Langa Bostan park. Immediately before it to the east stands the gate known in Turkish as the Yenikapı ("New Gate"). A Latin inscription commemorates its repair after the 447 earthquake[196] It is usually identified with the Jewish Gate of late Byzantine times.[197] Immediately to the west after the harbour lies the next gate, Davutpaşa Kapısı ("Gate of Davut Pasha"), usually identified with the Gate of Saint Aemilianus (Πόρτα τοῦ ἀγίου Αἰμιλιανοῦ, Porta tou hagiou Aimilianou), which is known to have stood at the junction of the sea wall with the city's original Constantinian Wall. That view is disputed by Janin, as the junction of the walls occurred considerably to the west from the modern gate's location.[198]

Further to the west, where the shoreline turns sharply south, stood the Gate of Psamathia (Πόρτα τοῦ Ψαμαθᾶ/Ψαμαθέως, Porta tou Psamatha/Psamatheos), modern Samatya Kapısı, leading to the suburb of the same name.[199] Further south and west lies the gate known today as Narlıkapı ("Pomegranate Gate"). Its Byzantine name is unknown, but is prominent on account of its proximity to the famed Monastery of Stoudios.[200]

Garrisons of the city

During the whole existence of the Byzantine Empire, the garrison of the city was quite small: the imperial guards and the small city watch (the pedatoura or kerketon) under the urban prefect were the only permanent armed force available. Any threat to the city would have to be dealt with by the field armies in the provinces, before it could approach the city itself. In times of need, such as the earthquake of 447 or the raids by the Avars in the early 7th century, the general population, organized in the guilds and the hippodrome factions, would be conscripted and armed, or additional troops would be brought in from the provincial armies.[201]

In the early centuries, the imperial guard consisted of the units of the Excubitores and Scholae Palatinae, which by the late 7th century had declined to parade-ground troops. At about that time Justinian II established the first new guards units to protect the imperial palace precinct, while in the 8th century the emperors, faced with successive revolts by the thematic armies and pursuing deeply unpopular iconoclastic policies, established the imperial tagmata as an elite force loyal to them. As the tagmata were often used to form the core of imperial expeditionary armies, they were not always present in or near the city. Only two of them, the Noumeroi and the Teicheiōtai, the palace guard units established by Justinian II, remained permanently stationed in Constantinople, garrisoned around the palace district or in various locations, such as disused churches, in the capital. The units present in the city at any one time were thus never very numerous, numbering a few thousands at best, but they were complemented by several detachments stationed around the capital, in Thrace and Bithynia.[202]

The small size of the city's garrison was due to the uneasiness of emperors and populace alike towards a permanent large military force, both for fear of a military uprising and because of the considerable financial burden its maintenance would entail. Furthermore, a large force was largely unnecessary, because of the inherent security provided by the city walls themselves. As historian John Haldon notes, "providing the gates were secured and the defenses provided with a skeleton force, the City was safe against even very large forces in the pre-gunpowder period."[203]

Fortifications around Constantinople

Anastasian Wall

_by_Florentine_cartographer_Cristoforo_Buondelmonte.jpg.webp)

Several fortifications were built at various periods in the vicinity of Constantinople, forming part of its defensive system. The first and greatest of these is the 56 km long Anastasian Wall (Gk. τεῖχος Ἀναστασιακόν, teichos Anastasiakon) or Long Wall (μακρὸν τεῖχος, makron teichos, or μεγάλη Σοῦδα, megalē Souda), built in the mid-5th century as an outer defence to Constantinople, some 65 km westwards of the city. It was 3.30 m thick and over 5 m high, but its effectiveness was apparently limited, and it was abandoned at some time in the 7th century for want of resources to maintain and men to garrison it. For centuries thereafter, its materials were used in local buildings, but several parts, especially in the remoter central and northern sections, are still extant.[204][205][206]

In addition, between the Anastasian Wall and the city itself, there were several small towns and fortresses like Selymbria, Region or the great suburb of Hebdomon ("Seventh", modern Bakırköy, so named from its distance of seven Roman miles from the Milion, the city's mile-marker), the site of major military encampments. Beyond the Long Walls, the towns of Bizye and Arcadiopolis covered the northern approaches. These localities were strategically situated along the main routes to the city, and formed the outer defenses of Constantinople throughout its history, serving to muster forces, confront enemy invasions or at least buy time for the capital's defenses to be brought in order. It is notable that during the final Ottoman siege, several of them, such as Selymbria, surrendered only after the fall of Constantinople itself. In Asia Minor, their role was mirrored by the cities of Nicaea and Nicomedia, and the large field camp at Malagina.[207]

Walls of Galata

.jpg.webp)

Galata, then the suburb of Sykai, was an integral part of the city by the early 5th century: the Notitia Urbis Constantinopolitanae of ca. 425 names it as the city's 13th region. It was probably fortified with walls in the 5th century, and under Justinian I it was granted the status of a city. The settlement declined and disappeared after the 7th century, leaving only the great tower (the kastellion tou Galatou) in modern Karaköy, that guarded the chain extending across the mouth of the Golden Horn.[208] After the sack of the city in 1204, Galata became a Venetian quarter, and later a Genoese extraterritorial colony, effectively outside Byzantine control. Despite Byzantine opposition, the Genoese managed to surround their quarter with a moat, and by joining their castle-like houses with walls they created the first wall around the colony. The Galata Tower, then called Christea Turris ("Tower of Christ"), and another stretch of walls to its north were built in 1349. Further expansions followed in 1387, 1397 and 1404, enclosing an area larger than that originally allocated to them, stretching from the modern district of Azapkapı north to Şişhane, from there to Tophane and thence to Karaköy.[209] After the Ottoman conquest, the walls were maintained until the 1870s, when most were demolished to facilitate the expansion of the city.[210] Today only the Galata Tower, visible from most of historical Constantinople, remains intact, along with several smaller fragments.[146]

Anadolu and Rumeli fortresses

The twin forts of Anadoluhisarı and Rumelihisarı lie to the north of Istanbul, at the narrowest point of the Bosphorus. They were built by the Ottomans to control this strategically vital waterway in preparation for their final assault on Constantinople. Anadoluhisarı (Turkish for "Fortress of Anatolia"), also called Akçehisar and Güzelcehisar ("beautiful fortress") in earlier times, was constructed by Sultan Bayezid I in 1394, and initially consisted of just a 25 m high, roughly pentagonal watchtower surrounded by a wall.[210] The much larger and more elaborate Rumelihisarı ("Fortress of Rumeli") was built by Sultan Mehmed II in just over four months in 1452. It consists of three large and one small towers, connected by a wall reinforced with 13 small watchtowers. With cannons mounted on its main towers, the fort gave the Ottomans complete control of the passage of ships through Bosphorus, a role evoked clearly in its original name, Boğazkesen ("cutter of the strait"). After the conquest of Constantinople, it served as a customs checkpoint and a prison, notably for the embassies of states that were at war with the Empire. After suffering extensive damage in the 1509 earthquake, it was repaired, and was used continuously until the late 19th century.[210]

See also

References

- Janin 1964, pp. 10–12

- Janin 1964, pp. 12–13

- Janin 1964, p. 13

- Janin 1964, pp. 13, 15

- Janin 1964, pp. 13, 16

- Janin 1964, pp. 16–19

- Janin 1964, pp. 19–20

- Janin 1964, pp. 21–23

- Bury 1923, p. 70

- Janin 1964, p. 263; Mango 2000, p. 176

- Kazhdan 1991, p. 519

- van Millingen 1899, pp. 15–18; Janin 1964, p. 26

- cf. Janin 1964, pp. 34–35

- Turnbull 2004, p. 9.

- Bardill 2004, p. 124

- Janin 1964, p. 263

- van Millingen 1899, pp. 32–33

- "Istanbul's ancient past unearthed". 26 March 2018. Retrieved 26 March 2018 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- Janin 1964, p. 264

- van Millingen 1899, pp. 29–30

- Mango 2000, pp. 175–176

- Mango 2001, p. 26

- van Millingen 1899, p. 29

- van Millingen 1899, pp. 18, 264

- van Millingen 1899, p. 21

- van Millingen 1899, p. 76

- Mango 1985, p. 25

- Janin 1964, pp. 264–265

- Asutay-Effenberger 2007, p. 2; Bardill 2004, p. 122; Philippides & Hanak 2011, p. 299

- Philippides & Hanak 2011, p. 299

- Bardill 2004, pp. 122–123; Meyer-Plath & Schneider 1943, p. 4

- Bardill 2004, p. 123; Meyer-Plath & Schneider 1943, p. 4; Philippides & Hanak 2011, pp. 299–302

- cf. Meyer-Plath & Schneider 1943, pp. 3–7; Philippides & Hanak 2011, pp. 302–304; van Millingen 1899, pp. 95–108

- Philippides & Hanak 2011, p. 304; For a survey of the repairs undertaken against the Ottoman threat in the last decades of Byzantium, cf. Philippides & Hanak 2011, pp. 304–306

- Philippides & Hanak 2011, pp. 306–307

- Meyer-Plath & Schneider 1943, p. 2

- van Millingen 1899, pp. 51, 53

- Turnbull 2004, pp. 11–13; Philippides & Hanak 2011, p. 309

- "From "opus craticium" to the "Chicago frame": Earthquake resistant traditional construction (2006)" (PDF). conservationtech.com. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- Turnbull 2004, pp. 12–13, 15; Philippides & Hanak 2011, pp. 307–308; Meyer-Plath & Schneider 1943, pp. 28–31

- Turnbull 2004, p. 12

- Meyer-Plath & Schneider 1943, pp. 28–31

- Turnbull 2004, p. 13

- Philippides & Hanak 2011, p. 309

- Philippides & Hanak 2011, p. 308

- Runciman 1990, p. 91

- van Millingen 1899, pp. 55–56

- van Millingen 1899, pp. 56–58

- Philippides & Hanak 2011, pp. 309–310

- Philippides & Hanak 2011, pp. 310–312

- Chen, Yuan Julian (11 October 2021). "Between the Islamic and Chinese Universal Empires: The Ottoman Empire, Ming Dynasty, and Global Age of Explorations". Journal of Early Modern History. 25 (5): 422–456. doi:10.1163/15700658-bja10030. ISSN 1385-3783. S2CID 244587800.

- Meyer-Plath & Schneider 1943, pp. 11–12

- van Millingen 1899, p. 59; Meyer-Plath & Schneider 1943, p. 12

- Meyer-Plath & Schneider 1943, pp. 13–15

- van Millingen 1899, p. 60; Meyer-Plath & Schneider 1943, pp. 37–39; Philippides & Hanak 2011, pp. 331–332

- Kazhdan 1991, p. 858

- Meyer-Plath & Schneider 1943, p. 41

- van Millingen 1899, pp. 67–68

- Barker 2008

- Meyer-Plath & Schneider 1943, pp. 41–42

- Kazhdan 1991, p. 859

- Mango 2000, p. 179

- Bury 1923, p. 71

- van Millingen 1899, pp. 60–62

- van Millingen 1899, pp. 62–63

- van Millingen 1899, p. 64

- Meyer-Plath & Schneider 1943, p. 39

- Mango 2000, p. 181

- Mango 2000, p. 186

- van Millingen 1899, pp. 65–66

- Mango 2000, pp. 181–186

- Mango 2000, pp. 183, 186

- van Millingen 1899, pp. 69–70

- van Millingen 1899, p. 70

- Bartusis 1997, pp. 143, 294

- Mango 2000, p. 182

- Majeska 1984, p. 412

- Bartusis 1997, pp. 110, 335

- Majeska 1984, pp. 414–415

- Nicol 1992, pp. 101–102

- Meyer-Plath & Schneider 1943, p. 42

- Meyer-Plath & Schneider 1943, pp. 63–64; Philippides & Hanak 2011, p. 320

- Choniates 1984, p. 398

- Philippides & Hanak 2011, p. 320

- Choniates 1984, p. 222

- Kantakouzenos 1831, p. 558

- Meyer-Plath & Schneider 1943, p. 63

- Philippides & Hanak 2011, p. 332

- van Millingen 1899, pp. 75–76; Philippides & Hanak 2011, p. 321

- Meyer-Plath & Schneider 1943, p. 64; Philippides & Hanak 2011, pp. 321–322

- van Millingen 1899, pp. 76–77

- Bartusis 1997, p. 41; van Millingen 1899, p. 77

- van Millingen 1899, pp. 77–78; Philippides & Hanak 2011, p. 333

- Meyer-Plath & Schneider 1943, pp. 64–66

- van Millingen 1899, pp. 78–80

- Meyer-Plath & Schneider 1943, pp. 12, 66

- van Millingen 1899, p. 80; Philippides & Hanak 2011, p. 333

- Asutay-Effenberger 2007, pp. 83–94; Philippides & Hanak 2011, p. 335

- van Millingen 1899, pp. 80–81; Philippides & Hanak 2011, pp. 323, 329–330