Gebhard Truchsess von Waldburg

Gebhard Truchsess von Waldburg (10 November 1547 – 31 May 1601[1]) was the archbishop-elector of Cologne from 1577 to 1588. After pursuing an ecclesiastical career, he won a close election in the cathedral chapter of Cologne over Ernst of Bavaria. After his election, he fell in love with and later married Agnes von Mansfeld-Eisleben, a Protestant canoness at the Abbey of Gerresheim. His conversion to Calvinism and announcement of religious parity in the electorate triggered the Cologne War.

| Gebhard Truchsess von Waldburg | |

|---|---|

| Elector-Archbishop of Cologne | |

Portrait by Hermann tom Ring, 1579 | |

| Prince-Elector-Archbishop of Cologne | |

| Reign | 3 October 1577 – 1588 |

| Predecessor | Salentin VII of Isenburg-Grenzau |

| Successor | Ernst of Bavaria |

| Dean, Strasbourg Cathedral | |

| Tenure | 1574 |

| Provost, Augsburg Cathedral | |

| Tenure | 1576 |

| Born | 10 November 1547 Heiligenberg |

| Died | 31 May 1601 (aged 53) Strasbourg |

| Burial | Strasbourg Cathedral |

| House | House of Waldburg |

| Father | William Seneschal of Waldburg |

| Mother | Johanna von Fürstenberg |

| Religion | Roman Catholic (until 1582) Calvinist (from 1582) |

On 19 December 1582, a proclamation in his name established parity for Catholics and Calvinists in the Electorate of Cologne, causing a scandal in the Roman Catholic Church and the Holy Roman Empire, and after his marriage in February 1583, he sought to convert the electorate into a dynastic dignity. For the next six years, his supporters fought those of the Roman Catholic dominated cathedral chapter for the right to hold the electorship and the archdiocese in the so-called Cologne War or Seneschal War. After brutal fighting, and the plundering of villages, cities, and abbeys throughout the electorate, Gebhard surrendered his claim and retired to Strasbourg. He died there in 1601 and was buried in the Cathedral.

Gebhard's conversion and marriage was the first major test of the principle of ecclesiastical reservation established in the Peace of Augsburg, 1555. His loss of the electorate strengthened the Catholic counter reformation in the northern German states, gave the Jesuits a stronghold in Cologne, and expanded the Wittelsbach family influence in imperial politics.

Family and early career

Gebhard was born in the Fürstenburg fortress of Heiligenberg, the second son of William, known as the younger, (6 March 1518 – 17 January 1566), Freiherr and Seneschal of Waldburg and an Imperial councilor, and his wife, Johanna v. Fürstenberg (1529–1589). His family was an old Swabian house and he was descended from the Jacobin line of the House: Jakob I Truchseß von Waldburg, also known as the Golden Knight (for his blond hair).[2] The family owned extensive properties that bordered on the Abbey of Kempten and various Habsburg territories in present-day southwestern Bavaria;[3] In 1429 and 1463, the three surviving sons of Johann II, Jakob, Everhard, and George, and their surviving sister Ursula, concluded a covenant of inheritance to protect the family property. In the future, they would occupy and own the property as one; the inheritance of the daughters could not exceed 4000 gulden. They guaranteed each other the right of first refusal on potential property sales.[2]

Gebhard's grandfather had been a commander for the Swabian League army in 1531; a cousin of his grandfather, Jörg Truchsess von Waldburg, also known as Bauernjörg, had been a commander of the imperial army in the Peasant Wars (1525).[4] His uncle, Otto (1514–73), was the bishop of Augsburg, later a Cardinal, and founded University of Dillingen in Augsburg.[5] His younger brother, Karl (1548–1593), trained for a military career; a second younger brother, Ferdinand, died at the siege at 's-Hertogenbosch in 1585.

As a younger son, Gebhard was prepared early for an ecclesiastical career. He received a broad, Humanist education, learned several languages, including Latin, Italian, French, and German, and studied history and theology.[6] After studying at the universities of Dillingen, Ingolstadt, Perugia, Louvain and elsewhere, he began his ecclesiastical career in 1560 at Augsburg, serving as prebendary in the Cathedral church. His life at Augsburg caused some scandal; Uncle Otto, the archbishop, petitioned the Duke of Bavaria to remonstrate with Gebhard about his conduct, which apparently led to some improvement in his behavior.[7] In 1561, he became a deacon at the cathedral in Cologne (1561–77), a canon of St. Gereon in Köln (1562–67), a canon in Strassburg (1567), in Ellwangen (1567–83), and in Würzburg (1569–70). In 1571, he became deacon of the Strassburg Cathedral, a position he held until his death in 1601. In 1576, by papal nomination, he became provost of the Cathedral in Augsburg. He would have drawn a stipend from all these positions.[8]

In December 1577, he was chosen elector of Cologne after a contest with Ernst of Bavaria, the youngest brother of the ruling Duke. He won the election by two votes.[9] Although it was not required of him, Gebhard agreed to be ordained a priest, which his predecessor had not done.[10]

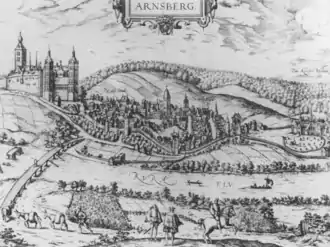

The initial years of his office were relatively uneventful. Gebhard continued some of the work of his predecessor, Salentin, chiefly in the reconstruction of the Arnsberg castle in Westphalia.[11]

Archbishop goes to war

Gebhard is chiefly noted for his conversion to the reformed doctrines, and for his marriage with the reportedly beautiful Agnes von Mansfeld-Eisleben, a canoness of Gerresheim.[12] After living in concubinage with Agnes for two years, he decided, perhaps by the persuasion of her brothers, to marry her, doubtless intending at the same time to resign his see. Other counsels, however, prevailed.[13][14]

Encouraged by Protestant supporters, including several in the cathedral chapter, he declared he would retain the electorate, and in December 1582, he formally announced his conversion to the reformed faith and the parity of Calvinism with Catholicism in the Electorate and archdiocese of Cologne. The marriage with Agnes was celebrated on 4 February 1583, and afterward Gebhard remained in possession of the see. This affair created a stir in the Holy Roman Empire.[15][14]

The clause concerning ecclesiastical reservation in the religious Peace of Augsburg was interpreted in one way by his friends, and in another way by his foes; the former held that he could retain his office, the latter insisted that he resign.[14] Hermann von Wied, a previous prince-elector and archbishop had also converted to Protestantism, but had resigned from his office; Gebhard's predecessor, Salentin von Isenburg-Grenzau, had resigned from the office upon his marriage, necessary to perpetuate his house. Unlike his predecessors, Gebhard proclaimed the Reformation, in the style of Calvinism, from the cathedral, angering Cologne's Catholic leadership and alienating the cathedral chapter.[16] He placed the evangelical confession on parity with the Catholic one; furthermore, Gebhard adhered not to the teachings of Martin Luther, but to those of John Calvin, a form of religious observation not approved of in the Augsburg conventions of 1555.[17]

Anticipating events, Gebhard had collected some troops and had taken measures to convert his subjects to Protestantism. In April 1583, he was excommunicated by Pope Gregory XIII; the unsuccessful candidate of 1577, Ernest, who was also bishop of Liège, Freising and Hildesheim, was chosen as the new elector. Initially, Gebhard was supported by Adolf von Neuenar and his own brother, Karl, who commanded most of his troops.[18] Although he sought assistance from several of the Lutheran princes of Germany, especially Augustus I, elector of Saxony, these princes were not enthusiastic to support Gebhard's cause; his association with the Calvinists was not to their liking. Henry of Navarre, later Henry IV of France, tried to form a coalition to aid Gebhard, but the only assistance which he obtained came from John Casimir, who took command of Gebhard's troops in the spring of 1583.[19] Later that summer, after fruitlessly marching the troops up and down the Rhine, a process of intimidation, he disbanded his army to administer the Palatinate of the Rhine for his ten-year-old nephew, the new Elector Palatine, Frederick IV.[20]

Ernest had the support of the previous Elector, now Salentin IX of Isenburg-Grenzau, Frederick, Duke of Saxe-Lauenburg, and, probably most important, several thousand Spanish troops hired by the pope. While representatives from the cathedral chapter, the seven imperial electors, the emperor, and the pope tried to resolve differences around the negotiating table, first in Frankfurt am Main, and then in Mühlhausen in Westphalia, the armies of both sides rampaged throughout the southern portion of the Electorate, called the Oberstift, plundering abbeys and convents, burning villages and small cities, and destroying crops, bridges, and roads.[21] None of the combatants were prepared to commit their troops in a fixed battle; it was far more lucrative, and safer as well, to use them in a show of force, intimidating the peasantry, besieging walled towns and small cities, and limiting trade and the sale of food-stuffs in the marketplaces.[22]

By the end of March, Salentin, Frederick, and the few thousand Spanish troops drove Gebhard from Bonn, then from Bad Godesberg; he and his wife took refuge into Vest Recklinghausen, a fiefdom of the electorate. There, he and Agnes encouraged a spurt of iconoclasm by their troops, alienating many heretofore supporters, including Hermann von Hatzfeld, seneschal of Balve.[23] Ferdinand, the brother of the rival archbishop, drove Gebhard and Agnes into the Netherlands; they escaped with approximately 1000 cavalry and some infantry.[24] Initially, they sought refuge in Delft with William the Silent. Living in the Netherlands, they became acquainted with Queen Elizabeth I of England's envoy, Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester, and entered into lengthy negotiations with Elizabeth's court to obtain support for his cause; these efforts failed to garner assistance for renewing the war either from the English queen or in any other quarter.[25]

By 1588, Gebhard's joint pain (Gelenkenschmerz) prevented him from riding a horse; the climate of Cologne, damp and cold, made his condition worse, so he relinquished his claim on the Electorate to the protection of Adolf von Neuenahr and Martin Schenck, which they pursued until their deaths later that year. In the summer 1588, Gebhard established his residence at Strassburg, where he had held the office of dean of the cathedral since 1574 and had maintained it concurrently with his position in Cologne.[26]

Consequences of conversion and marriage

.jpg.webp)

Gebhard's conversion and marriage were exceptionally costly, in terms of lives and property, and historians have made no actual estimate of its actual cost, although 19th century historians tend to criticize him for acting rashly. Perhaps its greater cost, however, lay in the impact his actions had on Protestantism and Catholicism in the northern territories of the German states. Although fighting continued until 1589, by early 1588, Ernst controlled most of the Electorate. Gebhard's defeat was a serious blow to Protestantism in northern Germany, and marks a critical stage in the history of the Reformation.[27] Bavarian Jesuits went to the Electoral territories to bring the population back to Catholicism, a process rife with violence and coercion.[28] Gebhard also opened the doors for Spanish incursions into the Rhineland; blocked from water access to the rebellious Dutch, Spanish military commanders sought a land route to the Dutch Provinces and by providing troop support for Ernst, they established valuable bridgeheads in the Rhine valley. Finally, the Cologne War marks the beginning of the "internationalization" of the German religious question, which was not resolved until 1650, after the disasters of the Thirty Years Wars.[29]

Later years

In 1589, Gebhard and his wife moved to Strasbourg, where he had held a prebendary position in the cathedral chapter since 1574, and had maintained concurrently with his position in Cologne. Before his arrival some trouble had arisen in the chapter when three excommunicated canons, refugees from the Cologne strife, persisted in retaining their offices after they had accepted the reformed doctrines.[30] He joined this party, which was strongly supported in the city, and took part in a double election to the bishopric in 1592. Despite some opposition, he retained his office until his death in 1601.[31]

Shortly after his marriage in 1583, Gebhard had written his Testament in which he left his estate to his brother, Karl, and a lifetime annuity to Agnes, and charged Karl with her safety and protection. When Karl died on 18 June 1593, and was buried in the Strasbourg cathedral, Gebhard wrote a codicil leaving Agnes to the care and protection of the Duke of Württemberg. He spent his last years diseased and crippled, and he died on 31 May 1601.[1] With great pomp and ceremony he was buried in a grave with Karl on 8 June 1601.[32][14]

Historical assessments

Historians have not been kind to Gebhard. E.A. Benians, in the Cambridge Modern History, was perhaps the most generous: "Few men personally insignificant have made more stir in the world."[33] Walter Goetz described him in less complimentary terms: he "was impelled by no great idea, nor could he claim through virile activity the title to any high striving ambition" and was "wanting in both depth and tenacity".[34] Goetz was not particularly kind to Ernst either: Ernst was not Gebhard's superior; the victory that placed him in the Electorate belonged to his brothers' influence and to that of the Curia (papacy), not to his own striving ambition; Ernst was, fundamentally, riding on the Counter Reformation tide that lifted all boats.[34] Philip Motley described Gebhard thus: despite his swearing an oath to renounce his see if he should marry, "the love of Truchsess for Agnes Mansfeld had created disaster, not only for himself but for all of Germany." Like Goetz, he describes both Gebhard and Ernst as cut from the same cloth: "two pauper Archbishops without men or means of their own were pushed back and forth, like puppets, by the highwaymen" on either side, while murder and robbery, in the name of Catholicism and Protestantism, were the "for a time the only motive or result of the contest."[35]

Citations and sources

Citations

- Franzen, August (1964), "Gebhard", Neue Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 6, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, p. 113; (full text online)

- (in German) Michaela Waldburg, Waldburg und Waldburger – Ein Geschlecht steigt auf in den Hochadel des Alten Reiches 2009, Accessed 15 October 2009.

- (in German) Casimir Bumiller, Adel im Wandel; 200 Jahre Mediatisierung in Oberschwaben, Ausstellungskatalog, Jan Thorbecke, Ostfildern, 2006, ISBN 978-3-7995-0216-0, Map, pp. 73–74.

- Heinz Wember, Family Genealogy table Archived 30 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Goetz, pp. 439–441.

- Ennen, pp. 6–8.

- (in German) "Gebhard Truchsess von Waldburg," the article on Gebhard, Allgemeine deutsche Biographic Worterbuch (ADBW), Leipzig, 1878, volume viii.

- (in German) Allgemeine deutsche Biographic Worterbuch.

- Ennen, p. 291. There may also have been skullduggery involved in keeping one of the members of the chapter from voting.

- Goetz, p. 440.

- While reconstructing the castle, Gebhard patronized the Netherlandish sculptor Willem Daniel van Tetrode. Tedtrode died in 1580 while completing some of the work at the Arnsberg. See: Anna Jolly, "Netherlandish Scultpors in Sixteenth Century Northern Germany and their Patrons," Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art. 27:3 (1999), pp. 119-143, p. 131 cited.

- Schiller, Friedrich, ed. Morrison, Alexander James William, History of the Thirty Years' War (in The Works of Frederick Schiller) (Bonn, 1846).

- The Cologne Stift Feud, 1583 at zum.de, accessed 8 July 2009.

- Chisholm 1911.

- Lossen, Max (1882). Der Kölnische Krieg: 1: Vorgeschichte 1561–1581 (in German). Gotha: F. A. Perthes.

- Herzog, Johann Jakob; et al., eds. (1909). "Gebhard Truchsess von Waldburg", and "Cologne War", The new Schaff-Herzog encyclopedia of religious knowledge. Vol. 4. New York: Funk and Wagnalls.

- Holborn, pp. 191–247; Wernham, pp. 338–345.

- The Cologne Stift Feud, 1583

- Holborn, pp. 191–247.

- Ennen, pp. 7–9; Holborn, pp. 191–247.

- Hennes, pp. 4–25.

- Ennen, pp. 7–9.

- (in German) Hennes, p. 69.

- Benians, p. 708.

- Tenison, p. 178.

- (in German) Aloys Meister, Der strassburger Kapitelstreit, 1583–1592, Strassbourg, Heitz, 1899, pp. 325–358.

- Brodek, pp. 400–401; Holborn, pp. 191–247.

- Scribner, pp. 217–241; Sutherland, pp. 587–625

- Holborn, pp. 191–247; Parker, Geoffrey (2004). The Flanders Army and the Spanish Road . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-54392-7.

- "Cologne". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 11 July 2009.

- Goetz, pp. 439–444.

- Benians, p. 709; Johannes Pappus, Angehengtem Programmate publico Rectoris Academiae, Abdankung Genealogia. (undated.) no page number. OCLC 257821109.

- Benians, p. 709.

- Goetz, p. 441.

- Quoted from Philip Motley,History of the United Netherlands, 1857, New York, Harper & Brothers, 1861–68, in Charles Marriott, Romance of the Rhine, London, Methuen, 1911, pp. 96–97.

Sources

- Benians, Ernest Alfred; Emerich, John; Dalberg, Edward; Acton, Baron; Ward, Sir Adolphus William; Prothero, G W; Leathes, Sir Stanley Mordaunt (1905). The Cambridge Modern History. New York: MacMillan. p. 708.

- Brodek, Theodor V. (1971). "Socio-Political Realities in the Holy Roman Empire". Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 1 (3): 395–405, 401–405. doi:10.2307/202618. JSTOR 202618.

- Bumiller, Casimir (2006). Adel im Wandel; 200 Jahre Mediatisierung in Oberschwaben, Ausstellungskatalog (in German). Ostfildern: Thorbecke. ISBN 978-3-7995-0216-0.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Gebhard Truchsess von Waldburg". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 11 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 546.

- Ennen, Leonard (1863–1880). Geschichte der Stadt Köln (in German).

- Goetz, Walter, "Gebhard II and the Counter Reformation in the Lower Rhinelands" in Herzog (1909).

- Hennes, Johann Heinrich (1878). Der Kampf um das Erzstift Köln zur Zeit der Kurfürsten (in German). Köln: DuMont-Schauberg.

- Jolly, Anna (1999). "Netherlandish Scultpors in Sixteenth Century Northern Germany and their Patrons". Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art. 27 (3): 119–143. doi:10.2307/3780979. JSTOR 3780979.

- Herzog, Johann Jakob; et al., eds. (1909). The new Schaff-Herzog encyclopedia of religious knowledge. Vol. 4. New York: Funk and Wagnalls.

- Holborn, Hajo (1959). A History of Modern Germany, The Reformation. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- "Cologne". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 11 July 2009.

- Lossen, Max (1882). Der Kölnische Krieg: 1: Vorgeschichte 1561–1581 (in German). Gotha: F. A. Perthes.

- Marriott, Charles Marriott (1911). Romance of the Rhine. London: Methuen.

- Meister, Aloys (1899). Der strassburger Kapitelstreit, 1583–1592 (in German). Strassbourg: Heitz. pp. 325–358.

- Parker, Geoffrey (2004). The Flanders Army and the Spanish Road . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-54392-7.

- Scribner, Robert (1976). "Why Was There No Reformation in Cologne?". Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research. 49 (120): 217–241. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2281.1976.tb01686.x.

- Sutherland, N.M. (1992). "Origins of the Thirty Years War and the Structure of European Politics". The English Historical Review. 107 (424): 587–625. doi:10.1093/ehr/cvii.ccccxxiv.587.

- Tenison, Eva Mabel (1932). Elizabethan England. Glasgow: Glasgow University Press.

- (in German) Waldburger, Michaela, Waldburg und Waldburger – Ein Geschlecht steigt auf in den Hochadel des Alten Reiches 2009, accessed 15 October 2009.