Generation X

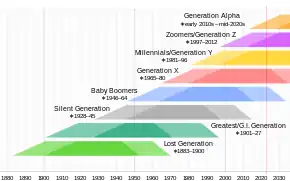

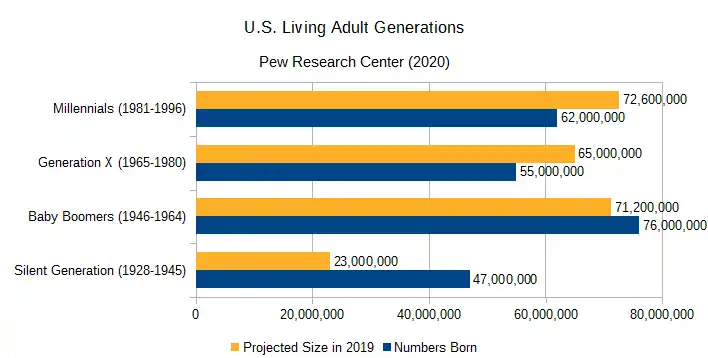

Generation X (often shortened to Gen X) is the demographic cohort following the baby boomers and preceding Millennials. Researchers and popular media use the mid-to-late 1960s as starting birth years and the late 1970s to early 1980s as ending birth years, with the generation being generally defined as people born from 1965 to 1980.[1] By this definition and U.S. Census data, there are 65.2 million Gen Xers[2] in the United States as of 2019.[3] Most members of Generation X are the children of the Silent Generation and early boomers;[4][5] Xers are also often the parents of millennials[4] and Generation Z.[6]

| Part of a series on |

| Social generations of the Western world |

|---|

|

As children in the 1970s and 1980s, a time of shifting societal values, Gen Xers were sometimes called the "latchkey generation," which stems from their returning as children to an empty home and needing to use the door key. This was a result of increasing divorce rates and increased maternal participation in the workforce prior to widespread availability of childcare options outside the home.

As adolescents and young adults in the 1980s and 1990s, Xers were dubbed the "MTV Generation" (a reference to the music video channel), sometimes being characterized as slackers, cynical, and disaffected. Some of the many cultural influences on Gen X youth included a proliferation of musical genres with strong social-tribal identity such as punk, post-punk, and heavy metal, in addition to later forms developed by Gen Xers themselves (e.g., grunge, grindcore and related genres). Film, both the birth of franchise mega-sequels and a proliferation of independent film (enabled in part by video) was also a notable cultural influence. Video games both in amusement parlours and in devices in western homes were also a major part of juvenile entertainment for the first time. Politically, in many Eastern Bloc countries, Generation X experienced the last days of communism and transition to capitalism as part of its youth. In much of the western world, a similar time period was defined by a dominance of conservatism and free market economics.

In midlife during the early 21st century, research describes them as active, happy, and achieving a work–life balance. The cohort has also been credited as entrepreneurial and productive in the workplace more broadly.

Terminology and etymology

The term Generation X has been used at various times to describe alienated youth. In the early 1950s, Hungarian photographer Robert Capa first used Generation X as the title for a photo-essay about young men and women growing up immediately following World War II. The term first appeared in print in a December 1952 issue of Holiday magazine announcing their upcoming publication of Capa's photo-essay.[7] From 1976 to 1981, English musician Billy Idol used the moniker as the name for his punk rock band.[8] Idol had attributed the name of his band to the book Generation X, a 1964 book on British popular youth culture written by journalists Jane Deverson and Charles Hamblett[9][10] — a copy of which had been owned by Idol's mother.[11] These uses of the term appear to have no connection to Robert Capa's photo-essay.[7]

The term acquired a modern application after the release of Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture, a 1991 novel written by Canadian author Douglas Coupland; however, the definition used there is "born in the late 1950s and 1960s", which is about ten years earlier than definitions that came later.[12][13][9][14] In 1987, Coupland had written a piece in Vancouver Magazine titled "Generation X" which was "the seed of what went on to become the book".[15][16] Coupland referenced Billy Idol's band Generation X in the 1987 article and again in 1989 in Vista magazine.[17] In the book proposal for his novel, Coupland writes that Generation X is "taken from the name of Billy Idol’s long-defunct punk band of the late 1970s".[18] However, in 1995 Coupland denied the term's connection to the band, stating that:

The book's title came not from Billy Idol's band, as many supposed, but from the final chapter of a funny sociological book on American class structure titled Class, by Paul Fussell. In his final chapter, Fussell named an 'X' category of people who wanted to hop off the merry-go-round of status, money, and social climbing that so often frames modern existence.[19][15]

Author William Strauss noted that around the time Coupland's 1991 novel was published the symbol "X" was prominent in popular culture, as the film Malcolm X was released in 1992, and that the name "Generation X" ended up sticking. The "X" refers to an unknown variable or to a desire not to be defined.[20][21][14] Strauss's coauthor Neil Howe noted the delay in naming this demographic cohort saying, "Over 30 years after their birthday, they didn't have a name. I think that's germane." Previously, the cohort had been referred to as Post-Boomers, Baby Busters (which refers to the drop in birth rates following the baby boom in the western world, particularly in the U.S.),[22] New Lost Generation, latchkey kids, MTV Generation, and the 13th Generation (the 13th generation since American independence).[8][20][17][23][24]

Demographics

United States

There are differences in Gen X population numbers depending on the date-range selected. In the U.S., using Census population projections, the Pew Research Center found that the Gen X population born from 1965 to 1980 numbered 65.2 million in 2019. The cohort is likely to overtake boomers in 2028.[3] A 2010 Census report counted approximately 84 million people living in the US who are defined by birth years ranging from the early 1960s to the early 1980s.[25]

In a 2012 article for the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, George Masnick wrote that the "Census counted 82.1 million" Gen Xers in the U.S. Masnick concluded that immigration filled in any birth year deficits during low fertility years of the late 1960s and early 1970s.[26] Jon Miller at the Longitudinal Study of American Youth at the University of Michigan wrote that "Generation X refers to adults born between 1961 and 1981" and it "includes 84 million people".[27] In their 1991 book Generations, authors Howe and Strauss indicated that the total number of Gen X individuals in the U.S. was 88.5 million.[28]

Impact of family planning programs

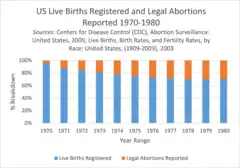

The birth control pill, introduced in 1960, was one contributing factor of declining birth rates. Initially, the pill spread rapidly amongst married women as an approved treatment for menstrual disturbance. However, it was also found to prevent pregnancy and was prescribed as a contraceptive in 1964. The pill, as it became commonly known, reached younger, unmarried college women in the late 1960s when state laws were amended and reduced the age of majority from 21 to ages 18–20.[29] These policies are commonly referred to as the Early Legal Access (ELA) laws.

Another major factor was abortion, only available in a few states until its legalisation in a 1973 US Supreme Court decision in Roe v. Wade. This was replicated elsewhere, with reproductive rights legislation passed, notably in the UK (1967), France (1975), West Germany (1976), New Zealand (1977), Italy (1978), and the Netherlands (1980). From 1973 to 1980, the abortion rate per 1,000 US women aged 15–44 increased from 16% to 29% with more than 9.6 million terminations of pregnancy practiced. Between 1970 and 1980, on average, for every 10 American citizens born, 3 were aborted.[30] However, increased immigration during the same period of time helped to partially offset declining birth-rates and contributed to making Generation X an ethnically and culturally diverse demographic cohort.[8][31]

Parental lineage

Generally, Gen Xers are the children of the Silent Generation and older baby boomers.[5]

Characteristics

Rising divorce rates and women workforce participation

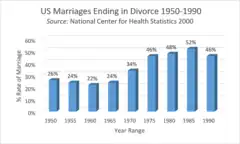

Strauss and Howe, who wrote several books on generations, including one specifically on Generation X titled 13th Gen: Abort, Retry, Ignore, Fail? (1993), reported that Gen Xers were children at a time when society was less focused on children and more focused on adults.[32] Xers were children during a time of increasing divorce rates, with divorce rates doubling in the mid-1960s, before peaking in 1980.[8][33][34] Strauss and Howe described a cultural shift where the long-held societal value of staying together for the sake of the children was replaced with a societal value of parental and individual self-actualization. Strauss wrote that society "moved from what Leslie Fiedler called a 1950s-era 'cult of the child' to what Landon Jones called a 1970s-era 'cult of the adult'".[32][35] The Generation Map, a report from Australia's McCrindle Research Center writes of Gen X children: "their Boomer parents were the most divorced generation in Australian history".[36] According to Christine Henseler in the 2012 book Generation X Goes Global: Mapping a Youth Culture in Motion, "We watched the decay and demise (of the family), and grew callous to the loss."[37]

The Gen X childhood coincided with the sexual revolution of the 1960s to 1980s, which Susan Gregory Thomas described in her book In Spite of Everything as confusing and frightening for children in cases where a parent would bring new sexual partners into their home.[38] Thomas also discussed how divorce was different during the Gen X childhood, with the child having a limited or severed relationship with one parent following divorce, often the father, due to differing societal and legal expectations. In the 1970s, only nine U.S. states allowed for joint custody of children, which has since been adopted by all 50 states following a push for joint custody during the mid-1980s.[39] Kramer vs. Kramer, a 1979 American legal drama based on Avery Corman's best-selling novel, came to epitomize the struggle for child custody and the demise of the traditional nuclear family.[40]

The rapid influx of boomer women into the labor force that began in the 1970s was marked by the confidence of many in their ability to successfully pursue a career while meeting the needs of their children. This resulted in an increase in latchkey children, leading to the terminology of the "latchkey generation" for Generation X.[41][42][43] These children lacked adult supervision in the hours between the end of the school day and when a parent returned home from work in the evening, and for longer periods of time during the summer. Latchkey children became common among all socioeconomic demographics, but this was particularly so among middle- and upper-class children.[42] The higher the educational attainment of the parents, the higher the odds the children of this time would be latchkey children, due to increased maternal participation in the workforce at a time before childcare options outside the home were widely available.[44][45][46][47] McCrindle Research Centre described the cohort as "the first to grow up without a large adult presence, with both parents working", stating this led to Gen Xers being more peer-oriented than previous generations.[36][48]

Conservative and neoliberal turn

Some older Gen Xers started high school in the waning years of the Carter presidency, but much of the cohort became socially and politically conscious during the Reagan Era. President Ronald Reagan, voted in office principally by the boomer generation,[49] embraced laissez-faire economics with vigor. His policies included cuts in the growth of government spending, reduction in taxes for the higher echelon of society, legalization of stock buybacks, and deregulation of key industries.[50] Measures had drastic consequences on the social fabric of the country even if, gradually, reforms gained acceptability and exported overseas to willing participants. The early 1980s recession saw unemployment rise to 10.8% in 1982; requiring, more often than not, dual parental incomes.[51] One-in-five American children grew up in poverty during this time. The federal debt almost tripled during Reagan's time in office, from $998 billion in 1981 to $2.857 trillion in 1989, placing greater burden of repayment on the incoming generation.[52]

Government expenditure shifted from domestic programs to defense. Remaining funding initiatives, moreover, tended to be diverted away from programs for children and often directed toward the elderly population, with cuts to Medicaid and programs for children and young families, and protection and expansion of Medicare and Social Security for the elderly population. These programs for the elderly were not tied to economic need. Congressman David Durenberger criticized this political situation, stating that while programs for poor children and for young families were cut, the government provided "free health care to elderly millionaires".[35][53]

The crack epidemic and AIDS

Gen Xers came of age or were children during the 1980s crack epidemic, which disproportionately impacted urban areas as well as the African-American community. The U.S. Drug turf battles increased violent crime. Crack addiction impacted communities and families. Between 1984 and 1989, the homicide rate for black males aged 14 to 17 doubled in the U.S., and the homicide rate for black males aged 18 to 24 increased almost as much. The crack epidemic had a destabilizing impact on families, with an increase in the number of children in foster care. In 1986, President Reagan signed the Anti-Drug Abuse Act to enforce strict mandatory minimum sentencing for drug users. He also increased the federal budget for supply-reduction efforts.[54][55]

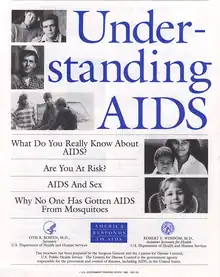

Fear of the impending AIDS epidemic of the 1980s and 1990s loomed over the formative years of Generation X. The emergence of AIDS coincided with Gen X's adolescence, with the disease first clinically observed in the U.S. in 1981. By 1985, an estimated one-to-two million Americans were HIV-positive. This particularly hit the LGBT community.[56] As the virus spread, at a time before effective treatments were available, a public panic ensued. Sex education programs in schools were adapted to address the AIDS epidemic, which taught Gen X students that sex could kill them.[57][58]

The rise of home computing

Gen Xers were the first children to have access to personal computers in their homes and at schools.[36] In the early 1980s, the growth in the use of personal computers exploded. Manufacturers such as Commodore, Atari, and Apple responded to the demand via 8-bit and 16-bit machines. This in turn stimulated the software industries with corresponding developments for backup storage, use of the floppy disk, zip drive, and CD-ROM.[59]

At school, several computer projects were supported by the Department of Education under United States Secretary of Education Terrel Bell's "Technology Initiative".[60] This was later mirrored in the UK's 1982 Computers for Schools programme[61] and, in France, under the 1985 scheme Plan Informatique pour Tous (IPT).[62]

The post–civil rights generation

In the U.S., Generation X was the first cohort to grow up post-integration after the racist Jim Crow laws. They were described in a marketing report by Specialty Retail as the kids who "lived the civil rights movement". They were among the first children to be bused to attain integration in the public school system. In the 1990s, Strauss reported Gen Xers were "by any measure the least racist of today's generations".[35][63] In the U.S., Title IX, which passed in 1972, provided increased athletic opportunities to Gen X girls in the public school setting.[64] Roots, based on the novel by Alex Haley and broadcast as a 12-hour series, was viewed as a turning point in the country's ability to relate to the afro-American history.[65]

Continued growth in college enrollments

In the U.S., compared to the boomer generation, Generation X was more educated than their parents. The share of young adults enrolling in college steadily increased from 1983, before peaking in 1998. In 1965, as early boomers entered college, total enrollment of new undergraduates was just over 5.7 million individuals across the public and private sectors. By 1983, the first year of Gen X college enrollments (as per Pew Research's definition), this figure had reached 12.2 million. This was an increase of 53%, effectively a doubling in student intake. As the 1990s progressed, Gen X college enrollments continued to climb, with increased loan borrowing as the cost of an education became substantially more expensive compared to their peers in the mid-1980s.[66] By 1998, the generation's last year of college enrollment, those entering the higher education sector totaled 14.3 million.[67] In addition, unlike Boomers and previous generations, women outpaced men in college completion rates.[68]

Adjusting to a new societal environment

For early Gen Xer graduates entering the job market at the end of the 1980s, economic conditions were challenging and did not show signs of major improvements until the mid-1990s.[69] In the U.S., restrictive monetary policy to curb rising inflation and the collapse of a large number of savings and loan associations (private banks that specialized in home mortgages) impacted the welfare of many American households. This precipitated a large government bailout, which placed further strain on the budget.[70] Furthermore, three decades of growth came to an end. The social contract between employers and employees, which had endured during the 1960s and 1970s and was scheduled to last until retirement, was no longer applicable. By the late 1980s, there were large-scale layoffs of boomers, corporate downsizing, and accelerated offshoring of production.[71]

On the political front, in the U.S. the generation became ambivalent if not outright disaffected with politics. They had been reared in the shadow of the Vietnam War and the Watergate scandal. They came to maturity under the Reagan and George H. W. Bush presidencies, with first-hand experience of the impact of neoliberal policies. Few had experienced a Democratic administration and even then, only, at an atmospheric level. For those on the left of the political spectrum, the disappointments with the previous boomer student mobilizations of the 1960s and the collapse of those movements towards a consumerist "greed is good" and "yuppie" culture during the 1980s felt, to a greater extent, hypocrisy if not outright betrayal. Hence, the preoccupation on "authenticity" and not "selling-out". The Revolutions of 1989 and the collapse of the socialist utopia with the fall of the Berlin Wall, moreover, added to the disillusionment that any alternative to the capitalist model was possible.[72]

Birth of the slacker

In 1990, Time magazine published an article titled "Living: Proceeding with Caution", which described those then in their 20s as aimless and unfocused. Media pundits and advertisers further struggled to define the cohort, typically portraying them as "unfocused twentysomethings". A MetLife report noted: "media would portray them as the Friends generation: rather self-involved and perhaps aimless...but fun".[74][75]

Gen Xers were often portrayed as apathetic or as "slackers", lacking bearings, a stereotype which was initially tied to Richard Linklater's comedic and essentially plotless 1991 film Slacker. After the film was released, "journalists and critics thought they put a finger on what was different about these young adults in that 'they were reluctant to grow up' and 'disdainful of earnest action'".[75][76] Ben Stiller's 1994 film Reality Bites also sought to capture the zeitgeist of the generation with a portrayal of the attitudes and lifestyle choices of the time.[77]

Negative stereotypes of Gen X young adults continued, including that they were "bleak, cynical, and disaffected". In 1998, such stereotypes prompted sociological research at Stanford University to study the accuracy of the characterization of Gen X young adults as cynical and disaffected. Using the national General Social Survey, the researchers compared answers to identical survey questions asked of 18–29-year-olds in three different time periods. Additionally, they compared how older adults answered the same survey questions over time. The surveys showed 18–29-year-old Gen Xers did exhibit higher levels of cynicism and disaffection than previous cohorts of 18–29-year-olds surveyed. However, they also found that cynicism and disaffection had increased among all age groups surveyed over time, not just young adults, making this a period effect, not a cohort effect. In other words, adults of all ages were more cynical and disaffected in the 1990s, not just Generation X.[78][79]

Rise of the Internet and the dot-com bubble

By the mid-late 1990s, under Bill Clinton's presidency, economic optimism had returned to the U.S.,[80] with unemployment reduced from 7.5% in 1992 to 4% in 2000.[81] Younger members of Gen X, straddling across administrations, politically experienced a "liberal renewal". In 1997, Time magazine published an article titled "Generation X Reconsidered", which retracted the previously reported negative stereotypes and reported positive accomplishments. The article cited Gen Xers' tendency to found technology startup companies and small businesses, as well as their ambition, which research showed was higher among Gen X young adults than older generations.[75] Yet, the slacker moniker stuck.[82][83] As the decade progressed, Gen X gained a reputation for entrepreneurship. In 1999, The New York Times dubbed them "Generation 1099", describing them as the "once pitied but now envied group of self-employed workers whose income is reported to the Internal Revenue Service not on a W-2 form, but on Form 1099".[84]

.jpg.webp)

Consumer access to the Internet and its commercial development throughout the 1990s witnessed a frenzy of IT initiatives. Newly created companies, launched on stock exchanges globally, were formed with dubitable revenue generation or cash flow.[85] When the dot-com bubble eventually burst in 2000, early Gen Xers who had embarked as entrepreneurs in the IT industry while riding the Internet wave, as well as newly qualified programmers at the tail-end of the generation (who had grown up with AOL and the first Web browsers), were both caught in the crash.[86] This had major repercussions, with cross-generational consequences; five years after the bubble burst, new matriculation of IT millennial undergraduates fell by 40% and by as much as 70% in some information systems programs.[87]

However, following the crisis, sociologist Mike Males reported continued confidence and optimism among the cohort. He reported "surveys consistently find 80% to 90% of Gen Xers self-confident and optimistic".[88] Males wrote "these young Americans should finally get the recognition they deserve", praising the cohort and stating that "the permissively raised, universally deplored Generation X is the true 'great generation', for it has braved a hostile social climate to reverse abysmal trends". He described them as the hardest-working group since the World War II generation. He reported Gen Xers' entrepreneurial tendencies helped create the high-tech industry that fueled the 1990s economic recovery.[88][89] In 2002, Time magazine published an article titled Gen Xers Aren't Slackers After All, reporting that four out of five new businesses were the work of Gen Xers.[63][90]

Response to 9/11

In the U.S., Gen Xers were described as the major heroes of the September 11 terrorist attacks by author William Strauss. The firefighters and police responding to the attacks were predominantly from Generation X. Additionally, the leaders of the passenger revolt on United Airlines Flight 93 were also, by majority, Gen Xers.[82][91][92] Author Neil Howe reported survey data which showed that Gen Xers were cohabiting and getting married in increasing numbers following the terrorist attacks. Gen X survey respondents reported that they no longer wanted to live alone.[93]

In October 2001, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer wrote of Gen Xers: "Now they could be facing the most formative events of their lives and their generation."[94] The Greensboro News & Record reported members of the cohort "felt a surge of patriotism since terrorists struck" by giving blood, working for charities, donating to charities, and by joining the military to fight the War on Terror.[95] The Jury Expert, a publication of The American Society of Trial Consultants, reported: "Gen X members responded to the terrorist attacks with bursts of patriotism and national fervor that surprised even themselves."[82]

Achieving a work-life balance

In 2011, survey analysis from the Longitudinal Study of American Youth found Gen Xers (defined as those who were then between the ages of 30 and 50) to be "balanced, active, and happy" in midlife and as achieving a work-life balance. The Longitudinal Study of Youth is an NIH-NIA funded study by the University of Michigan which has been studying Generation X since 1987. The study asked questions such as "Thinking about all aspects of your life, how happy are you? If zero means that you are very unhappy and 10 means that you are very happy, please rate your happiness." LSA reported that "mean level of happiness was 7.5 and the median (middle score) was 8. Only four percent of Generation X adults indicated a great deal of unhappiness (a score of three or lower). Twenty-nine percent of Generation X adults were very happy with a score of 9 or 10 on the scale."[96][97][98][99]

In 2014, Pew Research provided further insight, describing the cohort as "savvy, skeptical and self-reliant; they're not into preening or pampering, and they just might not give much of a hoot what others think of them. Or whether others think of them at all."[100] Furthermore, guides regarding managing multiple generations in the workforce describe Gen Xers as: independent, resilient, resourceful, self-managing, adaptable, cynical, pragmatic, skeptical of authority, and as seeking a work-life balance.[74][101][102][103]

Entrepreneurship as an individual trait

Individualism is one of the defining traits of Generation X, and is reflected in their entrepreneurial spirit.[104] In the 2008 book X Saves the World: How Generation X Got the Shaft but Can Still Keep Everything from Sucking, author Jeff Gordinier describes Generation X as a "dark horse demographic" which "doesn't seek the limelight". Gordiner cites examples of Gen Xers' contributions to society such as: Google, Wikipedia, Amazon.com, and YouTube, arguing that if boomers had created them, "we'd never hear the end of it". In the book, Gordinier contrasts Gen Xers to baby boomers, saying boomers tend to trumpet their accomplishments more than Gen Xers do, creating what he describes as "elaborate mythologies" around their achievements. Gordiner cites Steve Jobs as an example, while Gen Xers, he argues, are more likely to "just quietly do their thing".[5][105]

In a 2007 article published in the Harvard Business Review, authors Strauss and Howe wrote of Generation X: "They are already the greatest entrepreneurial generation in U.S. history; their high-tech savvy and marketplace resilience have helped America prosper in the era of globalization."[106] According to authors Michael Hais and Morley Winograd:

Small businesses and the entrepreneurial spirit that Gen Xers embody have become one of the most popular institutions in America. There's been a recent shift in consumer behavior and Gen Xers will join the "idealist generation" in encouraging the celebration of individual effort and business risk-taking. As a result, Xers will spark a renaissance of entrepreneurship in economic life, even as overall confidence in economic institutions declines. Customers, and their needs and wants (including Millennials) will become the North Star for an entire new generation of entrepreneurs.[107]

A 2015 study by Sage Group reports Gen Xers "dominate the playing field" with respect to founding startups in the United States and Canada, with Xers launching the majority (55%) of all new businesses in 2015.[108][109]

Income benefits of a college education

Unlike millennials, Generation X was the last generation in the U.S. for whom higher education was broadly financially remunerative. In 2019, the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis published research (using data from the 2016 Survey of Consumer Finances) demonstrating that after controlling for race and age, cohort families with heads of household with post-secondary education and born before 1980 have seen wealth and income premiums, while, for those after 1980, the wealth premium has weakened to a point of statistical insignificance (in part because of the rising cost of college). The income premium, while remaining positive, has declined to historic lows, with more pronounced downward trajectories among heads of household with postgraduate degrees.[110]

Parenting and volunteering

In terms of advocating for their children in the educational setting, author Neil Howe describes Gen X parents as distinct from baby boomer parents. Howe argues that Gen Xers are not helicopter parents, which Howe describes as a parenting style of boomer parents of millennials. Howe described Gen Xers instead as "stealth fighter parents", due to the tendency of Gen X parents to let minor issues go and to not hover over their children in the educational setting, but to intervene forcefully and swiftly in the event of more serious issues.[111] In 2012, the Corporation for National and Community Service ranked Gen X volunteer rates in the U.S. at "29.4% per year", the highest compared with other generations. The rankings were based on a three-year moving average between 2009 and 2011.[112][113]

Income differential with previous generations

A report titled Economic Mobility: Is the American Dream Alive and Well? focused on the income of males 30–39 in 2004 (those born April 1964 – March 1974). The study was released on 25 May 2007 and emphasized that this generation's men made less (by 12%) than their fathers had at the same age in 1974, thus reversing a historical trend. It concluded that, per year increases in household income generated by fathers/sons slowed from an average of 0.9% to 0.3%, barely keeping pace with inflation. "Family incomes have risen though (over the period 1947 to 2005) because more women have gone to work",[114][115][116][117] "supporting the incomes of men, by adding a second earner to the family. And as with male income, the trend is downward."[115][116][117]

Elsewhere

Although, globally, children and adolescents of Generation X will have been heavily influenced by U.S. cultural industries with shared global currents (e.g., rising divorce rates, the AIDS epidemic, advancements in ICT), there is not one U.S.-born raised concept but multiple perspectives and geographical outgrowths. Even within the period of analysis, inside national communities, commonalities will have differed on the basis of one's birth date. The generation, Christine Henseler also remarks, was shaped as much by real-world events, within national borders, determined by specific political, cultural, and historical incidents. She adds "In other words, it is in between both real, clearly bordered spaces and more fluid global currents that we can spot the spirit of Generation X."[118]

In 2016, a global consumer insights project from Viacom International Media Networks and Viacom, based on over 12,000 respondents across 21 countries,[119] reported on Gen X's unconventional approach to sex, friendship, and family,[120] their desire for flexibility and fulfillment at work[121] and the absence of midlife crisis for Gen Xers.[122] The project also included a 20 min documentary titled Gen X Today.[123]

Russia

In Russia, Generation Xers are referred to as "the last Soviet children", as the last children to come of age prior to the downfall of communism in their nation and prior to the Dissolution of the Soviet Union.[124] Those that reached adulthood in the 1980s and grew up educated in the doctrines of Marxism and Leninism found themselves against a background of economic and social change, with the advent of Mikhail Gorbachev to power and Perestroika. However, even before the collapse of the Soviet Union and the disbanding of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, surveys demonstrated that Russian young people repudiated the key features of the Communist worldview that their party leaders, schoolteachers, and even parents had tried to instill in them.[125] This generation, caught in the transition between Marxism–Leninism and an unknown future, and wooed by the new domestic political classes, remained largely apathetic.[126]

France

In France, "Generation X" is not as widely known or used to define its members. Demographically, this loosely denotes those born from the beginning of the 1960s to the early 1980s.[127] Although fertility rates started to fall in 1965, number of births in France only followed suit in 1975.[128] There is general agreement that, domestically, the event that is accepted in France as the separating point between the baby boomer generation and Generation X are the French strikes and violent riots of May 1968 with those of the generation too young to participate. Those at the start of the cohort are sometimes referred to as 'Génération Bof' because of their tendency to use the word 'bof', which, translated into English, means "whatever".[124]

The generation is closely associated with socialist François Mitterrand who served as President of France during two consecutive terms between 1981 and 1995 as most transitioned into adulthood during that period. Economically, Xers started when the new labour market was emerging and were the first to fully experience the advent of the post-industrial society. For those at the tail-end of the generation, educational and defence reforms, a new style baccalauréat général with three distinct streams in 1995 (the preceding programme, introduced in 1968) the 2002 licence-master-doctorat reform for first millennial graduates (DEUG, Maîtrise, DESS and DEA degrees no longer awarded), and the cessation of military conscription in 1997 (for those born after January 1979) are considered as new transition points to the next.[129]

Republic of Ireland

The term "Generation X" is used to describe Irish people born between 1965 and 1985; they grew up during The Troubles and the 1980s economic recession, coming of age during the Celtic Tiger period of prosperity in the 1990s onward.[130][131] The appropriateness of the term to Ireland has been questioned, with Darach Ó Séaghdha noting that "Generation X is usually contrasted with the one before by growing up in smaller and different family units on account of their parents having greater access to contraception and divorce – again, things that were not widely available in Ireland. [Contraception was only available under prescription in 1978 and without prescription in 1985; divorce was illegal until 1996.] However, this generation was in prime position to benefit from the Celtic Tiger, the Peace Process and liberalisations introduced on foot of EU membership and was less likely to emigrate than those that came before and after. You could say that in many ways, these are Ireland’s real boomers."[132]

Culturally, Britpop, Celtic rock, the trad revival, Father Ted, the 1990 FIFA World Cup and rave culture were significant.[133][134] The Divine Comedy song "Generation Sex" (1998) painted a picture of hedonism in the late 20th century, as well as its effect on the media.[135][136] David McWilliams' 2005 book The Pope's Children: Ireland's New Elite profiled Irish people born in the 1970s (just prior to the papal visit to Ireland), which was a baby boom that saw Ireland's population increase for the first time since the 1840s Great Famine. The Pope's Children were in position to benefit from the Celtic Tiger and the newly liberal culture, where the Catholic Church had significantly less social power.[137][138]

Political environment

The United Kingdom's Economic and Social Research Council described Generation X as "Thatcher's children" because the cohort grew up while Margaret Thatcher was Prime Minister from 1979 to 1990, "a time of social flux and transformation". Those born in the late 1960s and early 1970s grew up in a period of social unrest. While unemployment was low in the early 1970s, industrial and social unrest escalated. Strike action culminated in the "Winter of Discontent" in 1978–79, and the Troubles began to unfold in Northern Ireland. The turn to neoliberal policies introduced and maintained by consecutive conservative governments from 1979 to 1997 marked the end of the post-war consensus.[139]

Education

The almost universal dismantling of the grammar school system in Great Britain during the 1960s and the 1970s meant that the vast majority of the cohort attended secondary modern schools, relabelled comprehensive schools. Compulsory education ended at the age of 16.[140][139] As older members of the cohort reached the end of their mandatory schooling, levels of educational enrollment among older adolescents remained below much of the Western world. By the early 1980s, some 80% to 90% of school leavers in France and West Germany received vocational training, compared with 40% in the United Kingdom. By the mid-1980s, over 80% of pupils in the United States and West Germany and over 90% in Japan stayed in education until the age of eighteen, compared with 33% of British pupils.[141] There was, however, broadly a rise in education levels among this age range as Generation X passed through it.[142]

In 1990, 25% of young people in England stayed in some kind of full-time education after the age of 18, this was an increase from 15% a decade earlier.[143] Later, the Further and Higher Education Act 1992 and the liberalisation of higher education in the UK saw greater numbers of those born towards the tail-end of the generation gaining university places.[139]

Employment

The 1980s, when much of Generation X reached working age, was an era defined by high unemployment rates.[144] This was particularly true of the youngest members of the working aged population. In 1984, 26% of 16 to 24 year olds were neither in full-time education or participating in the workforce.[145] However, this figure did decrease as the economic situation improved reaching 17% by 1993.[146]

In midlife

Generation X were far more likely to have children out of wedlock than their parents. The number of babies being born to unmarried parents in England and Wales rose from 11% in 1979, a quarter in 1998, 40% by 2002 and almost half in 2012. They were also significantly more likely to have children later in life than their predecessors. The average age of a mother giving birth rose from 27 in 1982 to 30 in 2012. That year saw 29,994 children born to mothers over the age 40, an increase of 360% from 2002.[147]

A 2016 study of over 2,500 British office workers conducted by Workfront found that survey respondents of all ages selected those from Generation X as the hardest-working employees and members of the workforce (chosen by 60%).[148] Gen X was also ranked highest among fellow workers for having the strongest work ethic (chosen by 59.5%), being the most helpful (55.4%), the most skilled (54.5%), and the best troubleshooters/problem-solvers (41.6%).[149][150]

Political evolution

Ipsos MORI reports that at the 1987 and 1992 general elections, the first United Kingdom general elections where significant numbers of Generation X members could vote, a plurality of 18 to 24 year olds opted for the Labour Party by a small margin. The polling organisation's figures suggest that in 1987, 39% of that age group voted Labour, 37% for the Conservatives and 22% for the SDP–Liberal Alliance. Five years later, these numbers were fairly similar at 38% Labour, 35% Conservative and 19% Liberal Democrats, a party by then formed from the previously mentioned alliance. Both these elections saw a fairly significant lead for the Conservatives in the popular vote among the general population.[151]

At the 1997 General election where Labour won a large majority of seats and a comfortable lead in the popular vote, research suggests that voters under the age of 35 were more likely to vote Labour if they turned out than the wider electorate but significantly less likely to vote than in 1992. Analysts suggested this may have been due to fewer differences in policies between the major parties and young people having less of a sense of affiliation with particular political parties than older generations.[151][152] A similar trend continued at the 2001 and 2005 general elections as turnout dropped further among both the relatively young and the wider public.[153][154]

Voter turnout across the electorate began to recover from a 2001 low until the 2017 general election.[153] Generation X also became more likely to vote as they entered the midlife age demographics. Polling suggests a plurality of their age group backed the Conservatives in 2010 and 2015 but less overwhelming than much of the older generation.[155][156] At the 2016 EU membership referendum and 2017 general election, Generation X was split with younger members appearing to back remain and Labour and older members tending towards Leave and Conservative in a British electorate more polarised by age than ever before.[157][158] At the 2019 general election, voting trends continued to be heavily divided by age but a plurality of younger as well as older generation X members (then 39 to 55 year olds) voted Conservative.[159]

Germany

In Germany, "Generation X" is not widely used or applied. Instead, reference is made to "Generation Golf" in the previous West German republic, based on a novel by Florian Illies. In the east, children of the "Mauerfall" or coming down of the wall. For former East Germans, there was adaptation, but also a sense of loss of accustomed values and structures. These effects turned into romantic narratives of their childhood. For those in the West, there was a period of discovery and exploration of what had been a forbidden land.[160]

South Africa

In South Africa, Gen Xers spent their formative years of the 1980s during the "hyper-politicized environment of the final years of apartheid".[161]

Arts and culture

Music

Gen Xers were the first cohort to come of age with MTV. They were the first generation to experience the emergence of music videos as teenagers and are sometimes called the MTV Generation.[74][162] Gen Xers were responsible for the alternative rock movement of the 1990s and 2000s, including the grunge subgenre.[83][163] Hip hop has also been described as defining music of the generation, particularly artists such as Tupac Shakur, N.W.A., and The Notorious B.I.G.[164]

Punk rock

From 1974 to 1976, a new generation of rock bands arose, such as the Ramones, Johnny Thunders and the Heartbreakers, The Dictators in New York City, the Sex Pistols, the Clash, the Damned, and Buzzcocks in the United Kingdom, and the Saints in Brisbane. By late 1976, these acts were generally recognized as forming the vanguard of "punk rock", and as 1977 approached, punk rock became a major and highly controversial cultural phenomenon in the UK.[165] It spawned a punk subculture which expressed a youthful rebellion, characterized by distinctive styles of clothing and adornment (ranging from deliberately offensive T-shirts, leather jackets, studded or spiked bands and jewelry, as well as bondage and S&M clothes) and a variety of anti-authoritarian ideologies that have since been associated with the form.[166]

By 1977 the influence of punk rock music and its subculture became more pervasive, spreading throughout various countries worldwide.[167] It generally took root in local scenes that tended to reject affiliation with the mainstream.[168] In the late 1970s, punk experienced its second wave. Acts that were not active during its formative years adopted the style. While at first punk musicians were not Gen Xers themselves (many of them were late boomers, or Generation Jones),[169] the fanbase for punk became increasingly Gen X-oriented as the earliest Xers entered their adolescence, and it therefore made a significant imprint on the cohort.[170]

By the 1980s, faster and more aggressive subgenres such as hardcore punk (e.g., Minor Threat), street punk (e.g., the Exploited, NOFX) and anarcho-punk (e.g., Subhumans) became the predominant modes of punk rock. Musicians identifying with or inspired by punk often later pursued other musical directions, resulting in a broad range of spinoffs. This development gave rise to genres such as post-punk, new wave and later indie pop, alternative rock, and noise rock. Gen Xers were no longer simply the consumers of punk, they became the creators as well.[169] By the 1990s, punk rock re-emerged into the mainstream. Punk rock and pop punk bands with Gen X members such as Green Day, Rancid, The Offspring, and Blink-182 brought widespread popularity to the genre .[171]

Hard rock

Arguably in a similar way to punk, a sense of disillusionment, angst and anger catalysed hard rock and heavy metal to grow from the earlier influence of rock.

Post-punk

The energy generated by the punk movement launched a subsequent proliferation of weird and eclectic post-punk sub cultures, spanning new wave, goth, etc., and influencing the New Romantics.

Grunge

A notable example of alternative rock is grunge music and the associated subculture that developed in the Pacific Northwest of the U.S. Grunge song lyrics have been called the "...product of Generation X malaise".[173] Vulture commented: "the best bands arose from the boredom of latchkey kids". "People made records entirely to please themselves because there was nobody else to please" commented producer Jack Endino.[174]

Grunge lyrics are typically dark, nihilistic,[175] angst-filled, anguished, and often addressing themes such as social alienation, despair and apathy.[176] The Guardian wrote that grunge "didn't recycle banal cliches but tackled weighty subjects".[177] Topics of grunge lyrics included homelessness, suicide, rape,[178] broken homes, drug addiction, self-loathing,[179] misogyny, domestic abuse and finding "meaning in an indifferent universe".[177] Grunge lyrics tended to be introspective and aimed to enable the listener to see into hidden personal issues and examine depravity in the world.[172] Notable grunge bands include: Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Alice in Chains, Stone Temple Pilots and Soundgarden.[177][180]

Hip hop

The golden age of hip hop refers to hip hop music made from the mid-1980s to mid-1990s,[181] typically by artists originating from the New York metropolitan area.[182] The music style was characterized by its diversity, quality,[183] innovation[184] and influence after the genre's emergence and establishment in the previous decade.[185][186][187] There were various types of subject matter, while the music was experimental and the sampling eclectic.[188][189]

Artists associated with the era include LL Cool J, Run–D.M.C., Public Enemy, the Beastie Boys, KRS-One,[190] Eric B. & Rakim, De La Soul, Big Daddy Kane, EPMD, A Tribe Called Quest, Wu-Tang Clan, Slick Rick, Ultramagnetic MC's, and the Jungle Brothers.[191][192][193][194][187] Releases by these acts co-existed in this period with, and were as commercially viable as, those of early gangsta rap artists such as Ice-T, Geto Boys and N.W.A, the sex raps of 2 Live Crew and Too Short, and party-oriented music by acts such as Kid 'n Play, The Fat Boys, DJ Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince and MC Hammer.[195]

In addition to lyrical self-glorification, hip hop was also used as a form of social protest.[191] Lyrical content from the era often drew attention to a variety of social issues, including afrocentric living, drug use, crime and violence, religion, culture, the state of the American economy, and the modern man's struggle. Conscious and political hip hop tracks of the time were a response to the effects of American capitalism and former President Reagan's conservative political economy. According to Rose Tricia, "In rap, relationships between black cultural practice, social and economic conditions, technology, sexual and racial politics, and the institution policing of the popular terrain are complex and in constant motion". Even though hip hop was used as a mechanism for different social issues, it was still very complex with issues within the movement itself.[196]

There was also often an emphasis on black nationalism. Hip hop artists often talked about urban poverty and the problems of alcohol, drugs, and gangs in their communities.[197] Public Enemy's most influential song, "Fight the Power", came out at this time; the song speaks up to the government, proclaiming that people in the ghetto have freedom of speech and rights like every other American.[198]

Film

The economic accessibility of video mediums in the consumer market supported the growth and popularity of independent film.

Indie films

Gen Xers were largely responsible for the "indie film" movement of the 1990s, both as young directors and in large part as the film audiences which were fueling demand for such films.[83][163] In cinema, directors Kevin Smith, Quentin Tarantino, Sofia Coppola, John Singleton, Spike Jonze, David Fincher, Steven Soderbergh,[199][200] and Richard Linklater[201][202] have been called Generation X filmmakers. Smith is most known for his View Askewniverse films, the flagship film being Clerks, which is set in New Jersey circa 1994, and focuses on two convenience-store clerks in their twenties. Linklater's Slacker similarly explores young adult characters who were interested in philosophizing.[203]

While not a member of Gen X himself, director John Hughes has been recognized as having created classic 1980s teen films with early Gen X characters which "an entire generation took ownership of", including The Breakfast Club,[204][205] Sixteen Candles, Weird Science, and Ferris Bueller's Day Off.[206]

In France, a new movement emerged, the Cinéma du look, spearheaded by filmmakers Luc Besson, Jean-Jacques Beineix and Leos Carax. Although not Gen Xers themselves, Subway (1985), 37°2 le matin (English: Betty Blue; 1986), and Mauvais Sang (1986) sought to capture on screen the generation's malaise, sense of entrapment, and desire to escape.[207]

Franchise mega sequels

The birth of franchise mega-sequels in the science fiction, fantasy, and horror fiction genres, such as the epic space opera Star Wars and the Halloween franchise, had a profound and notable cultural influence.

Literature

The literature of early Gen Xers is often dark and introspective. In the U.S., authors such as Elizabeth Wurtzel, David Foster Wallace, Bret Easton Ellis, and Douglas Coupland captured the zeitgeist of this generation.[208] In France, Michel Houellebecq and Frédéric Beigbeder rank among major novelists whose work also reflect the dissatisfaction and melancholies of the cohort.[209] In the UK, Alex Garland, author of The Beach (1996), further added to the genre.

Health problems

While previous research has indicated that the likelihood of heart attacks was declining among Americans aged 35 to 74, a 2018 study published in the American Heart Association's journal Circulation revealed that this did not apply to the younger half of that cohort (controlling for age, Generation X have not seen a reduction in heart attack risk, versus previous generations). Data from 28,000 patients from across the United States who were hospitalized for heart attacks between 1995 and 2014 showed that a growing proportion were between the ages of 35 and 54. The proportion of heart-attack patients in this age group at the end of the study was 32%, up from 27% at the start of the study. This increase is most pronounced among women, for whom the number rose from 21% to 31%. A common theme among those who suffered from heart attacks is that they also had high-blood pressure, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease. These changes have been faster for women than for men. Experts suggest a number of reasons for this. Conditions such as coronary artery disease are traditionally viewed as a man's problem, and as such female patients are not considered high-risk. More often than in previous generations, Generation X women are both the primary caretakers of their families and full-time employees, reducing time for self-care.[210]

Offspring

Generation X are usually the parents of Generation Z,[211][212][213] and sometimes millennials.[4] Jason Dorsey, who works for the Center of Generational Kinetics, observed that like their parents from Generation X, members of Generation Z tend to be autonomous and pessimistic. They need validation less than the millennials and typically become financially literate at an earlier age, as many of their parents bore the full brunt of the Great Recession.[214]

References

- Twenge, Jean (26 January 2018). "How Are Generations Named?". Trend. The Pew Charitable Trusts. Archived from the original on 30 August 2018. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- "Gen Xer". Lexico. Oxford Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- Fry, Richard (28 April 2020). "Millennials overtake Baby Boomers as America's largest generation". Pew Research Center. Archived from the original on 28 April 2020. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- Strauss, William; Howe, Neil (2000). Millennials Rising: The Next Great Generation. Cartoons by R.J. Matson. New York: Vintage Original. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-375-70719-3. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- Gordinier, Jeff (27 March 2008). X Saves the World: How Generation X Got the Shaft but Can Still Keep Everything from Sucking. Viking Adult. ISBN 978-0-670-01858-1.

- Williams, Alex (18 September 2015). "Move Over, Millennials, Here Comes Generation Z". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 19 September 2015. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- Ulrich, John Mcallister; Harris, Andrea L. (2003). GenXegesis: Essays on Alternative Youth (Sub)culture. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-87972-862-5. Archived from the original on 3 February 2023. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- Klara, Robert (4 April 2016). "5 Reasons Marketers Have Largely Overlooked Generation X". Adweek. Archived from the original on 1 December 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- "The original Generation X". BBC News. 1 March 2014. Archived from the original on 11 September 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- Robb, John (2012). Punk Rock: An Oral History. PM. p. 240. ISBN 978-1-60486-005-4. OCLC 934936262.

- "Generation X - A Punk Rock History with Pictures". punk77.co.uk. Archived from the original on 1 February 2016. Retrieved 11 July 2010.

- Coupland, Douglas (1991). Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture. Macmillan Publishers. p. inside front dust jacket flap. ISBN 9780312054366.

- Cunningham, Guy Patrick (2015). "Generation X". In Ciment, James (ed.). Postwar America: An Encyclopedia of Social, Political, Cultural, and Economic History, Volume 2. Routledge. p. 596. ISBN 978-1-317-46235-4.

The expression was later popularized by the American author Douglas Coupland, who borrowed it for the title of his 1991 novel Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture.

- Raphelson, Samantha (6 October 2014). "From GIs To Gen Z (Or Is It iGen?): How Generations Get Nicknames". NPR. Archived from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Coupland, Douglas (2 September 2007). "Genesis X". Vancouver Magazine. Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- Coupland, Douglas (September 1987). "Generation X". Vancouver Magazine. Retrieved 24 March 2019. See original magazine pages 164, 165, 167, 168, 169. The story is continued on p. 194, which was not scanned.

- Coupland, Doug (1989). "Generation X" (PDF). Vista. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 October 2009. Retrieved 4 July 2009.

- Doody, Christopher (2011). "X-plained: The Production and Reception History of Douglas Coupland's Generation X". Papers of the Bibliographical Society of Canada. 49 (1): 5–34. Archived from the original on 20 July 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- Coupland, Douglas (June 1995). "Generation X'd". Details Magazine. Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- "Demographic Profile - America's Gen X" (PDF). MetLife. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Neil Howe & William Strauss discuss the Silent Generation on Chuck Underwood's Generations. 2001. pp. 49:00. Archived from the original on 21 April 2015. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- II, Ronald L. Jackson; Jackson, Ronald L.; Hogg, Michael A. (29 June 2010). Encyclopedia of Identity. SAGE. ISBN 978-1-4129-5153-1. Archived from the original on 3 February 2023. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- Lipton, Lauren (10 November 1911). "The Shaping of a Shapeless Generation : Does MTV Unify a Group Known Otherwise For its Sheer Diversity?". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- Jackson, Ronald L.; Hogg, Michael A. (2010). Encyclopedia of Identity. SAGE. p. 307. ISBN 978-1-4129-5153-1. Archived from the original on 3 February 2023. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- "U.S. Census Age and Sex Composition: 2010" (PDF). U.S. Census. 11 May 2011. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 June 2011. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- Masnick, George (28 November 2012). "Defining the Generations". Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- Miller, Jon (Fall 2011). "The Generation X Report: Active, Balanced, and Happy: These Young Americans are not Bowling Alone" (PDF). Longitudinal Study of American Youth – University of Michigan. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 January 2020. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- William Strauss, Neil Howe (1991). Generations. New York: Harper Perennial. p. 318. ISBN 978-0-688-11912-6.

- Golding and Katz, Claudia & Lawrence (August 2002). "The Power of the Pill: Oral Contraceptives and Women's Career and Marriage Decisions". Journal of Political Economy. 110 (4): 730–770. doi:10.1086/340778. JSTOR 10.1086/340778. S2CID 221286686.

- Stanley K, Henshaw (2008). "Trends in the characteristics of women obtaining abortions, 1974 to 2004". Alan Guttmacher Institute. Archived from the original on 14 June 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Markert, John (Fall 2004). "Demographics of Age: Generational and Cohort Confusion" (PDF). Journal of Current Issues in Research & Advertising. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 September 2012. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- Howe, Neil (1993). 13th Gen: Abort, Retry, Ignore, Fail?. Vintage. ISBN 978-0-679-74365-1.

- Dulaney, Josh (27 December 2015). "A Generation Stuck in the Middle Turns 50". PT Projects. Archived from the original on 18 May 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- Dawson, Alene (25 September 2011). "Gen X women, young for their age". LA Times. Archived from the original on 13 August 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- Strauss, William. "What Future Awaits Today's Youth in the New Millennium?". Angelo State University. Archived from the original on 8 August 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- "The Generation Map" (PDF). McCrindle Research. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 June 2019. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- Henseler, Christine (2012). Generation X Goes Global: Mapping a Youth Culture in Motion. Routledge. pp. xx. ISBN 978-0-415-69944-0.

- Thomas, Susan (22 October 2011). "All Apologies: Thank You for the 'Sorry'". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 15 April 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- Thomas, Susan (2011). In Spite of Everything. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6882-1.

- Hanson, Peter (2002). The Cinema of Generation X: A Critical Study of Films and Directors. McFarland & Co. pp. 45. ISBN 978-0-7864-1334-8.

- Blakemore, Erin (9 November 2015). "The Latchkey Generation: How Bad Was It?". JSTOR Daily. Archived from the original on 12 November 2015. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- Clack, Erin. "Study probes generation gap.(Hot copy: an industry update)". HighBeam Research. Archived from the original on 3 May 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- "What's The Defining Moment of Your Generation?". NPR.org. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- Thomas, Susan (21 October 2011). "All Apologies: Thank You for the 'Sorry'". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 15 April 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- "A Teacher's Guide to Generation X". Edutopia. Archived from the original on 23 March 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- Thomas, Susan (9 July 2011). "The Divorce Generation". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 9 April 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- Toch, Thomas (19 September 1984). "The Making of 'To Save Our Schools, To Save Our Children': A Conversation With Marshall Frady". Education Week. Archived from the original on 26 April 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- Corry, John (4 September 1984). "A Look at Schools in U.S." The New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 April 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- Gitlin, Martin (2011). The Baby Boomer Encyclopedia. Greenwood. pp. 160. ISBN 978-0-313-38218-5.

- Amadeo, Kimberly (31 January 2020). "Reaganomics". The Balance. Archived from the original on 25 May 2021. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- "The Rise in Dual Income Households". Pew Research Center. 18 June 2015. Archived from the original on 4 April 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- di Lorenzo, Stefano (2017). Reaganomics: The Roots of Neoliberalism. Independently Published. ISBN 978-1-9731-6329-9.

- Holtz, Geoffrey (1995). Welcome to the Jungle: The Why Behind Generation X. St. Martin's Griffin. pp. 49–50. ISBN 978-0-312-13210-1. Archived from the original on 3 February 2023. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- Fryer, Roland (April 2006). "Measuring Crack Cocaine and Its Impact" (PDF). Harvard University Society of Fellows: 3, 66. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 October 2013. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- "Yuppies, Beware: Here Comes Generation X". Tulsa World. 9 July 1991. Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- Haltikis, Perry (2 February 2016). "The Disease That Defined My Generation". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- "Generation X Reacts to AIDS". National Geographic Channel. 2016. Archived from the original on 27 April 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- Halkitis, Perry (2 February 2016). "The Disease That Defined My Generation". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 9 August 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- Clark Northrup, Cynthia (2003). The American economy : a historical encyclopedia. ABC Clio. pp. 144. ISBN 978-1-57607-866-2.

- Saettler, Paul (1990). The evolution of American educational technology. Libraries Unlimited. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-87287-613-2.

- Younie, Sarah (2013). Teaching with Technologies: The Essential Guide. McGraw-Hill Education (UK). p. 20. ISBN 978-0-335-24619-9.

- Mourot, Jean J. (2013). La dernière classe 1984-1990. Le Scorpion Brun. p. 71. ISBN 979-10-92559-00-2.

- "Generation X". Specialty Retail. Summer 2003. Archived from the original on 23 June 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- Underwood, Chuck. "America's Generations With Chuck Underwood - Generation X". PBS. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- Erickson, Tamara J (2009). What's Next, Gen X?: Keeping Up, Moving Ahead, and Getting the Career You Want. Harvard Business Review Pres. ISBN 978-1-4221-2064-4.

- US Congress, Senate Committee on Finance Staff (1999). Education Tax Proposals: Hearing Before the Committee on Finance. US Government Printing Office, 1999. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-16-058193-9.

- "Total fall enrollment in degree-granting institutions, by control and type of institution: 1965 to 1998". National Center for Education Statistics. July 2000. Archived from the original on 1 January 2023. Retrieved 3 February 2023.

- Bialik, Kristen (14 February 2019). "Millennial life: How young adulthood today compares with prior generation". Pew Research Center. Archived from the original on 8 February 2021. Retrieved 3 February 2023.

- Ericksson, Tamara (2009). What's Next, Gen X?: Keeping Up, Moving Ahead, and Getting the Career You Want. Harvard Business Review Press. ISBN 978-1-4221-2064-4.

- Walsh, Carl E (1993). "What caused the 1990-91 Recession?". Economic Review: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco: 33.

- . Erickson, Tamara (2012). What's Next, Gen X?: Keeping Up, Moving Ahead, and Getting the Career You Want. Harvard Business Pres. ISBN 978-1-4221-5615-5.

- Erickson, Tamara (2010). What's Next, Gen X?: Keeping Up, Moving Ahead, and Getting the Career You Want. Harvard Business Press. ISBN 978-1-4221-5615-5.

- Williams, Alex (9 May 2012). "Skateboarding Past a Midlife Crisis (Published 2012)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 January 2022.

- "The MetLife Study of Gen X: The MTV Generation Moves into Mid-Life" (PDF). MetLife. April 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- Gross, David (16 July 1990). "Living: Proceeding With Caution". Time. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ScrIibner, Sara (11 August 2013). "Generation X gets really old: How do slackers have a midlife crisis?". Salon. Archived from the original on 19 June 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- Roberts, Soraya (March 2019). "Reality Bites Captured Gen X With Perfect Irony". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 1 January 2023. Retrieved 3 February 2023.

- "Generation X not so special: Malaise, cynicism on the rise for all age groups". Stanford University. Archived from the original on 14 August 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- "Oldsters Get The Gen X Feeling". SCI GOGO. 29 August 1998. Archived from the original on 18 August 2016. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

- Weinstein, Deena (2015). Rock'n America: A Social and Cultural History. University of Toronto Press. p. 237. ISBN 978-1-4426-0018-8.

- "President Bill Clinton's Economic Policies". The Balance. Archived from the original on 24 May 2022. Retrieved 3 February 2023.

- Keene, Douglas (29 November 2011). "Generation X members are "active, balanced and happy". Seriously?". The Jury Expert – The Art and Science of Litigation Advocacy. Archived from the original on 3 July 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- Hornblower, Margot (9 June 1997). "Generation X Reconsidered". Time. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- Ellin, Abby (15 August 1999). "Preludes; A Generation of Freelancers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- Smith, Kalen. "History of the Dot-Com Bubble Burst and How to Avoid Another". Money Crashers. Archived from the original on 25 September 2022. Retrieved 3 February 2023.

- Wang, Cynthia (2019). 100 Questions and Answers About Gen X Plus 100 Questions and Answers About Millennials. Front Edge Publishing. ISBN 978-1-64180-048-8.

- Torres-Coronas, Teresa (2008). Encyclopedia of Human Resources Information Systems: Challenges in e-HRM: Challenges in e-HRM. IGI Global. p. 230. ISBN 978-1-59904-884-0.

- Males, Mike (26 August 2001). "The True 'Great Generation'". LA Times. Archived from the original on 4 July 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- Reddy, Patrick (10 February 2002). "Generation X Reconsidered; 'Slackers' No More. Today's Young Adults Have Fought Wars Fiercely, Reversed Unfortunate Social Trends and Are Proving Themselves to be Another 'Great Generation'". The Buffalo News. Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- Chatzky, Jean (31 March 2002). "Gen Xers Aren't Slackers After All". Time. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- Koidin, Michelle (11 October 2001). "After September 11 Events Hand Generation X a 'Real Role to Play'". Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

- Koidin, Michelle (11 October 2001). "Events Hand Generation X A 'Real Role to Play'". LifeCourse Associates. Archived from the original on 19 October 2016. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- "Neil Howe on Gen X and 9/11". CNN. 2001. Archived from the original on 29 September 2019 – via youtube.com.

- Klondin, Michelle (11 October 2001). "After September 11 Events Hand Generation X a 'Real Role to Play'". Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

- Johnson, Maria (20 September 2001). "Greatness Alive in Generation X Young Americans Show Patriotism in the Wake of the Terrorist Attacks Sept. 11". Greensboro News & Record.

- Miller, Jon (Fall 2011). "The Generation X Report: Active, Balanced, and Happy" (PDF). Longitudinal Study of American Youth – University of Michigan. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 January 2020. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- "NSF funds launch of a new LSAY 7th grade cohort in 2015 NIH-NIA fund continued study of original LSAY students". University of Michigan. 2011. Archived from the original on 6 June 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- "Long-term Survey Reveals Gen Xers Are Active, Balanced and Happy". National Science Foundation. 25 October 2011. Archived from the original on 7 August 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- Dawson, Alene (27 October 2011). "Study says Generation X is balanced and happy". CNN. Archived from the original on 30 June 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- Taylor, Paul (5 June 2014). "Generation X: America's neglected 'middle child'". Pew Research. Archived from the original on 18 June 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- "CREATING A CULTURE OF INCLUSION -- LEVERAGING GENERATIONAL DIVERSITY: At-a-Glance" (PDF). University of Michigan. 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 August 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- Eames, David (6 March 2008). "Jumping the generation gap". New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- White, Doug (23 December 2014). "What to Expect From Gen-X and Millennial Employees". Entrepreneur. Archived from the original on 9 August 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- Sirias, Danilo (September 2007). "Comparing the levels of individualism/collectivism between baby boomers and generation X: Implications for teamwork". Management Research News. doi:10.1108/01409170710823467. Archived from the original on 27 January 2019. Retrieved 3 February 2023.

- Stephey, M.J. (16 April 2008). "Gen-X: The Ignored Generation?". Time. Archived from the original on 20 June 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- Howe, Neil (June 2007). "The next 20 years: How customer and workforce attitudes will evolve". Harvard Business Review. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- Winograd, Morley; Hais, Michael (2012). "Why Generation X is Sparking a Renaissance in Entrepreneurship". Archived from the original on 9 March 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- "2015 State of the Startup". sage. 2015. Archived from the original on 21 October 2016. Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- Iudica, David (12 September 2016). "The overlooked influence of Gen X". Yahoo Advertising. Archived from the original on 21 October 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- Emmons, William R.; Kent, Ana H.; Ricketts, Lowell R. (2019). "Is College Still Worth It? The New Calculus of Falling Returns" (PDF). Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. 101 (4): 297–329. doi:10.20955/r.101.297-329. S2CID 211431474. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 October 2019.

- Howe, Neil. "Meet Mr. and Mrs. Gen X: A New Parent Generation". AASA – The School Superintendents Association. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- "Volunteering and Civic Life in America: Generation X Volunteer Rates". Corporation for National and Community Service. 27 November 2012. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- "Volunteering in the United States" (PDF). Bureau of Labor Statistics – U.S. Department of Labor. 22 February 2013. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 January 2004. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- "Civilian Labor Force Participation Rate: Women". FRED: Economic Data. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. 1950–2018. Archived from the original on 9 March 2018. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- "Civilian Labor Force Participation Rate: Men". FRED: Economic Data. Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis. January 1948. Archived from the original on 17 May 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- Isabel Sawhill, PhD; Morton, John E. (2007). "Economic Mobility: Is the American Dream Alive and Well?" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2013. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- Ellis, David (25 May 2007). "Making less than dad did". CNN. Archived from the original on 7 July 2010. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- Henseler, Christine (2012). Generation X Goes Global: Mapping a Youth Culture in Motion. Routledge. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-415-69944-0.

- Rodriguez, Ashley. "Generation X's rebellious nature helped reinvent adulthood". Quartz. Archived from the original on 20 October 2016. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- "Gen X's Unconventional Approach To Sex, Friendship and Family". Viacom International Insights. 22 September 2016. Archived from the original on 20 October 2016. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- "At Work, Gen X Want Flexibility and Fulfilment More Than a Corner Office". Viacom International Insights. 29 September 2016. Archived from the original on 20 October 2016. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- "For Gen X, Midlife Is No Crisis". Viacom International Insights. 4 October 2016. Archived from the original on 20 October 2016. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- Taylor, Anna (20 October 2016). "Gen X Today: The Documentary". Viacom International Insights. Archived from the original on 3 February 2023. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- McCrindle, Mark. "Generations Defined" (PDF). McCrindle Research Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 June 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- Bernbaum, John A (9 July 1996). "Russia's "Generation X": Who Are They?". beam-inc.org. Archived from the original on 18 July 2021. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- Stanley, Alessandra (6 June 1996). "To Win Russia's 'Generation X', Yeltsin Is Pumping Up the Volume". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 6 September 2020. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- Sally, Marthaler (2020). Partisan De-Alignment and the Blue-Collar Electorate in France. Springer Nature Switzerland AG. p. 59. ISBN 978-3-030-35467-1.

- Monnier, Alain. "Le baby-boom : suite et fin". Population & Sociétés (in French). 2 (431): 4. Archived from the original on 3 February 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- Henseler, Christine (2014). Generation X Goes Global: Mapping a Youth Culture in Motion. London: Routledge. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-415-69944-0.

- Harrington, Suzanne (19 February 2017). "All grown up and in their forties: Whatever happened to Generation X?". Irish Examiner. Archived from the original on 27 June 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- Dame, Marketing Communications: Web | University of Notre. "Ireland's Generation X? with Belinda McKeon & Barry McCrea". Keough-Naughton Institute for Irish Studies. Archived from the original on 27 June 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ó Séaghdha, Darach (2 June 2019). "The Irish For: Is Ireland more progressive now because we didn't have baby boomers?". TheJournal.ie. Archived from the original on 27 June 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- "Millennials: spirituality, sex, and the screen". Theos Think Tank. Archived from the original on 27 June 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- Waters, John. "Generation X? No, it's Generation Zzzzzz". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 6 February 2022. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- "Gen X-spotting: they ascended the ladder just as the Celtic Tiger was being birthed". independent. Archived from the original on 27 June 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- Greenwald, Matthew. "The Divine Comedy: 'Generation Sex' – Review". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 6 February 2022. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- Aodha, Gráinne Ní (19 May 2018). "If you were named John Paul after the Pope's 1979 visit, RTÉ is looking for you". TheJournal.ie. Archived from the original on 27 June 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- Ward, Conor. "Born in 1981, am I part of Generation X or Generation Y?". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 6 February 2022. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- "Thatcher's children: the lives of Generation X". Economic and Social Research Council. 11 March 2016. Archived from the original on 29 July 2016. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- Reitan, Earl Aaron (2003). The Thatcher Revolution: Margaret Thatcher, John Major, Tony Blair, and the Transformation of Modern Britain, 1979–2001. p. 14. ISBN 9780742522039. Archived from the original on 3 February 2023. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- MacDowall, David (2000). Britain in Close-up: An In-depth Study of Contemporary Britain. Longman. Archived from the original on 3 February 2023. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- Bolton, Paul (27 November 2012). "Education: Historical statistics". House of commons Library. Archived from the original on 25 May 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- Coughlan, Sean (26 September 2019). "The symbolic target of 50% at university reached". BBC News. Archived from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- "The Thatcher years in statistics". BBC News. 9 April 2013. Archived from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- Smith, Nicola (15 December 2009). "1980s recession was worse for young people". Left Foot Forward. Archived from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- "Youth Unemployment: Déjà Vu?" (PDF). University of Sterling. January 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 October 2016.

- Duggan, Oliver (11 July 2013). "Half of all babies born out of wedlock". The Independent. Archived from the original on 3 February 2023. Retrieved 3 August 2021.

- "The UK State of Work Report" (PDF). Workfront. 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 22 July 2021.