Women in Peru

Women in Peru represent a minority in both numbers and legal rights. Although historically somewhat equal to men, after the Spanish conquest the culture in what is now Peru became increasingly patriarchal. The patriarchal culture is still noticeable. Contraceptive availability is not enough for the demand, and over a third of pregnancies end in abortion. Maternal death rates are also some of the highest in South America.[4]

Cindy Arlette Contreras Bautista, lawyer and women's rights advocate | |

| General Statistics | |

|---|---|

| Maternal mortality (per 100,000) | 68 (2015)[1] |

| Women in parliament | 27.7% (2017)[1] |

| Women over 25 with secondary education | 57.1% (2017)[1] |

| Women in labour force | 69.0% (2017)[1] |

| Gender Inequality Index[2] | |

| Value | 0.380 (2021) |

| Rank | 90th out of 191 |

| Global Gender Gap Index[3] | |

| Value | 0.749 (2022) |

| Rank | 37th out of 146 |

| Part of a series on |

| Women in society |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

The Peruvian Government has begun efforts to combat the high maternal mortality rate and lack of female political representation, as well as violence against women. However, the efforts have not yet borne fruit.

History

Andean civilization is traditionally somewhat egalitarian for men and women, with women allowed to inherit property from their mothers. After the Spanish conquered the Inca Empire, the culture became more patriarchal; and the resulting society has been described as being machista.[5][6]

During the republican revolutions in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the concept of separate spheres (private vs. public) became a legally debated issue in Peru.[7] Determining a clear distinction of the boundaries between private crimes and public crimes became significant because only public crimes could be directly prosecuted by the state.[8] During this time, public crimes were crimes that affected the state or society, while private crimes only harmed the individual committing the act. Although all civil cases were considered to be private, some private crimes could potentially affect the public.[8] Crimes such as theft and inflicting serious bodily injuries had previously only been prosecuted by the wishes of the plaintiff; however, during the early republic, these crimes were pursued based on the prosecutors’ and judges’ own agendas.[8] In contrast, crimes such as slander, rape, or anything related to honor was treated the same as before. Victims of these crimes had to do substantially more work than victims of theft and serious physical injuries.[9] In order for their case to be considered, these victims had to report their cases themselves, and had to file a formal complaint as well as provide witnesses. These plaintiffs were expected to decide whether the crime itself or reporting the crime to the court would create greater harm to their honor.[9]

Even though there could be circumstances in which rape or seduction would disturb society enough to make it a public crime, to give prosecutors the power to file charges would "disturb the peace and secrecy that should exist in the domestic sphere". For the same reason, physical injuries resulting from the "punishment" of dependence (servants, wives, children) were usually considered "private", crimes and the rights of the perpetrators carried more weight than the protections due to the victims, who were not, after all, citizens. Even as republican judicial officials tried to balance the demands of public and domestic order, they continue to trend, begun with the Bourbon reforms, of increasingly claiming jurisdiction in those cases pertaining to marriage, family, and sexual honor, in which the affected parties did press charges. Formerly, such cases had fallen primarily within the jurisdiction of the church.[9]

During this republican state, men who were contributed to the public sphere and were either married, between the age of 21 and 25, owned property, had an independent profession, or paid taxes were granted "citizenship status".[10] This enabled them to easily obtain protection of their civil liberties. Women, on the other hand, did not receive the same benefits because their roles were confined to the private sphere. The labor traditionally done by women (sewing, cooking, child-rearing, etc.) became worthless because it was no longer recognized as a public contribution, but just a part of the private (patriarchal) system in Peru. Legally, women held little protections, as it was seen as their husband or father's job to protect them.[11]

Legally, women were not protected by the new system. As a result of this, they faced many hardships. For example, domestic abuse was an ongoing problem mainly because abuse and rape were considered to be "private crimes". The state classified these heinous acts this way because they did not want to disrupt the male patriarchal society.

Women were mainly defined by their sexual purity and domestic serving abilities. Poor women, in particular, had a hard time conforming to the "republican mother" look and could not base claims on their rights or duties as mothers.[12] Furthermore, if they were convicted of a crime, they were seen as “unnatural” and were often prevented from being released early from prison.[13] Although women like Maria Toledo and Juana Pia fought to be released early because of good behavior and because they were the sole supporter of their children, the prosecutor argued that the women would negatively influence their children. On the contrary, men were seen as the hard-working provider for the family and received more advantages than women. For example, a few months before Toledo's petition was denied, an “honorable man’s” sentence was reduced because his wife had indicated on the appeal that he was her family's sole provider.[14]

This misogynist system prevailed for many decades.

On June 17, 1956, Peruvian women voted for the first time in general elections, after years of mobilization by women like María Jesús Alvarado, Adela Montesinos, Zoila Aurora Cáceres, Elvira García y García, and Magda Portal, among others. Peru was the next-to-last country in Latin America to fully enfranchise women.[15]

During the internal conflict in Peru beginning in the 1980s, some families became matriarchal, with approximately 78 percent of migrant families being headed by women. In shantytowns, women established soup kitchens (comedores) and worked together to ensure that their families received enough food to eat.[5][16]

The abuses during the conflict have caused both mental and physical problems in women. Identification papers, necessary for the execution of civil rights like voting, were also destroyed en masse. As of 2007, approximately 18.1 percent of Peruvian women are living without the necessary documents, as opposed to 12.2 percent of men.[17] Even today, women from indigenous tribes may be treated disrespectfully by authority figures. The same applies to poor women.[18]

In the ninetieth century Peru, women were treated as if their lives had been divided in two different ways. One part of a woman's life was considered private which included the work that women did and how they were treated inside the home. By declaring the work that women do as private, this then lowers their status in Peru being their work was not valued. Private work was not a way for women to gain a larger role of independence. The other part of a woman's life was considered public, and in this case, it was hard for women to fulfill a large amount of public activity. Public activity for women was a tough area being that women's work was worthless therefore, they were not important in the community.[19]

Forced sterilization

The Peruvian armed forces, frustrated with the inability of the Alan García administration to handle the nation's crises, including the internal conflict in Peru, began to draft Plan Verde to overthrow his government and establish a neoliberal government.[20][21] In one of the plan's volumes titled Driving Peru into the XXI century, the military planned to sterilize impoverished citizens in what Rospigliosi described as "ideas frankly similar to the Nazis", with the military writing that "the general use of sterilization processes for culturally backward and economically impoverished groups is convenient", describing these groups as "unnecessary burdens" and that "given their incorrigible character and lack of resources ... there is only their total extermination".[22] Rospigliosi states "an understanding was established between Fujimori, Montesinos and some of the military officers" involved in Plan Verde prior to the inauguration of Alberto Fujimori following the 1990 Peruvian general election.[23][21] Fujimori would go on to adopt many of the policies outlined in Plan Verde.[21][23]

President Alberto Fujimori (in office from 1990 to 2000) has been accused of genocide and crimes against humanity as a result of a sterilization program, the National Population Program, put in place by his administration. During his presidency, Fujimori conducted a program of forced sterilizations against indigenous Quechuas and the Aymaras women, under the guise of a "public health plan".[24][25] Forced sterilization against indigenous and poor women was practiced on a large scale in Peru. The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, published in 2003, notes that during the internal conflict in Peru, there were numerous cases of women being forcibly sterilized; it was estimated that hundreds of thousands of mostly rural women were sterilized under deception or with insufficient consent in the 1990s as part of a campaign intended to combat poverty.[26] The commission said that the program was assisted by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and the Nippon Foundation.[27][28] Other estimates included more than 300,000 Peruvian women being forcibly sterilized.[29]

The International Criminal Court condemned the Fujimori government's actions, describing them as crimes against humanity.[29] A case against former president Alberto Fujimori involving thousands of woman plaintiffs has been on hold since 2002.[30] In order to face trial, the Supreme Court of Chile would have to authorize the prosecution of Fujimori for the forced sterilization charges since the charges were not included in his extradition request.[30]

Education

Female literacy is lower than male literacy in Peru: only 94.3% of females (15 and older) are literate, compared to 97.2% of males, according to 2016 estimates.[31]

Indigenous women of Peru travel less than men. As such, they tend to be less fluent in Spanish, the national language of Peru. This may lead to difficulties when they must speak with outsiders, who often do not speak the indigenous language.[18] Although women have a higher illiteracy rate than men, an increasing number of women are receiving higher education.[5]

Demographics

Women are a slight minority in Peru; in 2010 they represented 49.9 percent of the population. Women have a life expectancy of 74 years at birth, five years more than men.[32]

Latest estimates suggest that the population of Peru is Amerindian 45%, mestizo (mixed Amerindian and white) 37%, white 15%, black, Japanese, Chinese, and other 3%.[33] More than 8 out of 10 people are Catholics.[33]

Although Peru has an ethnically diverse population, discrimination by ethnic lines is common, particularly against amerindians and blacks; gender often interacts with ethnic origin; this may mean that "an indigenous woman may only ever work as a maid".[34]

Maternal and reproductive health

Women who live in poverty are less likely to give birth in a health center or be attended by a health care worker.[35] Peru has one of the highest maternal death rates in South America, with the government noting 185 deaths per 100,000 live births, and the United Nations estimating the number at 240 per 100,000 live births. In order to combat those high figures, the government released a strategic plan in 2008 to reduce the total to 120 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births.[36]

Of these maternal deaths, 46 percent occur during the first six weeks after birth.[37] Amnesty International notes that economic discrimination is one of the factors, with women in affluent areas receiving better health care than those in rural areas. Gender and ethnic discrimination in health care also exist.[38]

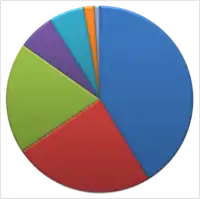

According to the 2007 census, the causes of maternal death in Peru were as follows:[37]

The age of consent in Peru has changed several times during recent years, and has been subject to political debates,[39][40] but today it is fixed at 14, regardless of gender and/or sexual orientation, in accordance with a 2012 decision of the Constitutional Court of Peru.[41] Teenage pregnancies are not uncommon. They are often the result of rape by a male relative.[42]

When giving birth, indigenous mothers may avoid going to clinics due to unfamiliarity with the techniques used. They instead prefer to use traditional practices, with which they are comfortable. [18]The lack of health staff able to speak indigenous languages is also a problem.[43]

Although contraceptives are used in Peru, they are more common in urban areas. An estimated 13.3 percent of women in rural areas are in need of contraceptives that are unavailable, as opposed to 8.7 percent of urban women.[44] Although therapeutic abortion is legal,[45] and an estimated 35 percent of pregnancies result in abortion,[42] regulation and implementation has been controversial, with the only clear guidelines (in Arequipa) withdrawn under pressure from anti-abortion groups. There have been instances where mothers have been forced to carry babies to term at large personal risk.[45]

The HIV/AIDS rate in Peru was estimated in 2012 at 0.4% of adults aged 15–49.[46]

Family life

By law, Peruvian women must be 16 years old to marry;[32] prior to 1999, it was 14. A 2004 survey by the United Nations estimates that 13 percent of women between the ages of 15 and 19 have been married. In some families, the mother is the head of the household.[6] Some ethnic groups, such as the Asháninka, practice polygamy.[5] The husband and wife share responsibility for household affairs, but in approximately 75% of marriages, finances are handled by the wives.[32]

Despite the fact that married Peruvian men occasionally openly take lovers, divorce is difficult to obtain.[5] In a divorce, custody of children under the age of seven is generally awarded to the mother. Custody of those over seven is generally awarded by gender. If a parent is deemed unfit, the children can be sent to live with the other parent.[47]

Domestic violence

The OECD notes that women in Peru are subject to abuse, with almost half suffering from violence. The most common form of abuse is psychological. There are also reports of female genital mutilation as a rite of passage during puberty.[47] The government has attempted to address the issues, establishing the National Programme against Family Violence and Abuse in 2001, and passing a law requiring local authorities to deal with domestic abuse and stipulating punishments for rape and spousal rape.[32] Legal action against perpetrators of abuse is slow and ineffectual.[42] In 1999 Peru repealed the law which stated that a rapist would be exonerated, if after the assault he and his victim married.[48]

The principal law dealing with domestic violence is Ley de Protección frente a la Violencia Familiar (Law for Protection from Family Violence).[49] It was first enacted in 1993, has been strengthened in 1997, and thereafter modified several times, in order to broaden its scope: by 2010, this law had already been amended five times.[50]

Some abusive husbands were caught in the general rise in criminal prosecution, particularly when their drunken or violent behavior threatened public as well as domestic order. In 1852, for example, shoemaker Laurencio Salazar was arrested for knocking his wife unconscious. Salazar, on previous occasions not only injured his wife but also killed animals for spite and cut his brother-in-law's hand, was dangerously violent. The republican courts defined vaguely the level of violence necessary to constitute assault in domestic cases. Between 1784 and 1824, there were only two worthy cases filed by mothers de parte under the category of physical or verbal violence but neither made it till the end. In opposition, about half of accused rapists after independence were convicted despite their efforts. Going further, the penalties for rape convictions were "generally stricter than those for nonsexual assault: several months in jail while performing public labor and/or providing a dowry for the young woman".[51]

Economy

The majority of rural women work in farming,[5] or take care of household chores.[6] On average, they earn 46 percent less than male workers.[52]

Beginning in the 1990s, women increasingly entered service industries to replace men. They were hired because the employers could pay them less and believed that they would not form unions. During that period, labour rights were revoked for women workers.[53]

Gender equality

.jpg.webp)

Discrimination based on gender is forbidden by the government of Peru, and a piece of legislation was passed in 2000 that outlawed discrimination. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) noted that discrimination is practiced, in particular with regard to women's land rights, and that women in Peru generally have higher levels of poverty and unemployment. Those who have jobs have difficulty holding senior positions. The OECD has rated the degree of gender discrimination in Peru as low on the Social Institutions and Gender Index.[32]

Informal land-dispute resolution systems are common, and rural women are often discriminated.[54] Women's access to land is not well protected; in 2002, only 25 percent of land titles were given to women, and under an "informal ownership" system the husband may sell property without his wife's consent.[47] In 2014, new laws have improved the access of indigenous people to land.[55]

Politically, women in Peru have been subordinated to men and had little power. Twenty percent of those elected in 2001 were women. Female politicians are often from richer families, as women from a lower income bracket must deal with housework.[56] Recent laws have required a quota of representatives in Congress to be women. Despite this, the levels of women's political representation remain below the 30% quota target.[57] As of 2014, there were 22.3% women in parliament.[58]

References

- Footnotes

- "Table 5: Gender Inequality Index - Human Development Reports 2017". United Nations Development Programme. Archived from the original on 28 November 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- "Human Development Report 2021/2022" (PDF). HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORTS. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 September 2022. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- "Global Gender Gap Report 2022" (PDF). World Economic Forum. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 July 2022. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

- "Table 5: Gender Inequality Index - Human Development Reports 2015". United Nations Development Programme. Archived from the original on 28 November 2015. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- Barrett 2002, p. 83.

- Crabtree 2002, p. 11.

- Habermas, Jurgen (1989). The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Caulfield, Sueann; Chambers, Sarah; Putnam, Lara (2005). Honor, Status, and Law in Modern America. Duke University Press. p. 27.

- Caulfield, Sueann; Chambers, Sarah; Putnam, Lara (2005). Honor, Status, and Law in Modern America. Duke University Press. pp. 27–28.

- Caulfield, Sueann; Chambers, Sarah; Putnam, Lara (2005). Honor, Status, and Law in Modern America. Duke University Press. p. 29.

- Chambers, Sarah (2005). Honor, Status, and Law in Modern Latin America. Durham: Duke University Press. pp. 27–49.

- Caulfield, Sueann; Chambers, Sarah; Putnam, Lara (2005). Honor, Status, and Law in Modern America. Duke University Press. p. 35.

- Caulfield, Sueann; Chambers, Sarah; Putnam, Lara (2005). Honor, Status, and Law in Modern America. Duke University Press. p. 37.

- Caulfield, Sueann; Chambers, Sarah; Putnam, Lara (2005). Honor, Status, and Law in Modern America. Duke University Press. p. 36.

- "El voto femenino en el Perú". elperuano.pe (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2018-07-16. Retrieved 2018-07-16.

- Crabtree 2002, p. 46.

- Amnesty International 2009, pp. 26–27.

- Amnesty International 2009, p. 22.

- Mentioned in, Caulfield, Sueann, et al. "Private Crimes, Public Order: Honor, Gender, and the Law in Early Republican Peru". Honor, Status, and Law in Modern Latin America, Duke University Press, 2005, pp. 33–37.

- Burt, Jo-Marie (September–October 1998). "Unsettled accounts: militarization and memory in postwar Peru". NACLA Report on the Americas. Taylor & Francis. 32 (2): 35–41. doi:10.1080/10714839.1998.11725657.

the military's growing frustration over the limitations placed upon its counterinsurgency operations by democratic institutions, coupled with the growing inability of civilian politicians to deal with the spiraling economic crisis and the expansion of the Shining Path, prompted a group of military officers to devise a coup plan in the late 1980s. The plan called for the dissolution of Peru's civilian government, military control over the state, and total elimination of armed opposition groups. The plan, developed in a series of documents known as the "Plan Verde," outlined a strategy for carrying out a military coup in which the armed forces would govern for 15 to 20 years and radically restructure state-society relations along neoliberal lines.

- Alfredo Schulte-Bockholt (2006). "Chapter 5: Elites, Cocaine, and Power in Colombia and Peru". The politics of organized crime and the organized crime of politics: a study in criminal power. Lexington Books. pp. 114–118. ISBN 978-0-7391-1358-5.

important members of the officer corps, particularly within the army, had been contemplating a military coup and the establishment of an authoritarian regime, or a so-called directed democracy. The project was known as 'Plan Verde', the Green Plan. ... Fujimori essentially adopted the 'Plan Verde,' and the military became a partner in the regime. ... The autogolpe, or self-coup, of April 5, 1992, dissolved the Congress and the country's constitution and allowed for the implementation of the most important components of the 'Plan Verde.'

- Rospigliosi, Fernando (1996). Las Fuerzas Armadas y el 5 de abril: la percepción de la amenaza subversiva como una motivación golpista. Lima, Peru: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos. pp. 28–40.

- Avilés, William (Spring 2009). "Despite Insurgency: Reducing Military Prerogatives in Colombia and Peru". Latin American Politics and Society. Cambridge University Press. 51 (1): 57–85. doi:10.1111/j.1548-2456.2009.00040.x. S2CID 154153310.

- "Mass sterilisation scandal shocks Peru". 24 July 2002. Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 17 April 2018 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- "Stérilisations forcées des Indiennes du Pérou". monde-diplomatique.fr. 1 May 2004. Archived from the original on 10 May 2014. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-12-03. Retrieved 2021-11-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - McMaken, Ryan (2018-10-26). "How the U.S. Government Led a Program That Forcibly Sterilized Thousands of Poor Peruvian Women in the 1990s | Ryan McMaken". Foundation for Economic Education. Archived from the original on 2021-08-04. Retrieved 2021-08-04.

- "Informe final sobre la aplicación de la anticoncepción quirúrgica voluntaria (AQV) en los años 1990-2000" (PDF). Congress of Peru. June 2002. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-05-21. Retrieved 2022-02-06.

- Papaleo, Cristina (12 February 2021). "Peru: Hope for the victims of forced sterilizations | DW | 12.02.2021". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 2022-02-06. Retrieved 2022-02-06.

- "Peru's Fujimori can't be tried over forced sterilizations for now". France 24. 2021-12-03. Archived from the original on 2022-02-06. Retrieved 2022-02-06.

- "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Archived from the original on 24 November 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- OECD 2010, p. 128.

- "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- Collyns, Dan (13 June 2010). "Peru's minorities battle racism". BBC News. Archived from the original on 9 May 2018. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- Amnesty International 2009, p. 25.

- Amnesty International 2009, p. 11.

- Amnesty International 2009, p. 20.

- Amnesty International 2009, p. 12.

- Lindsay Goldwert (2007-06-22). "Peru Lowers Age Of Consent To 14". CBS News. Archived from the original on 2010-03-10. Retrieved 2009-12-02.

- "Pleno Reconsidero Exoneracion de Sedunda Votacion a Proyecto Sobre Libertad Sexual" [House Reconsidered and Excluded Second Vote for Project on Sexual Freedom] (in Spanish). El Heraldo. 2007-06-27. Archived from the original on 2012-04-01. Retrieved 2010-09-02.

- "Demanda de inconstitucionalidad interpuesta por diez mil seiscientos nueve ciudadanos contra el artículo 1° de la Ley N° 28704 que modifica el artículo 173°, inciso 3° del Código Penal, sobre delito de violación sexual contra víctima entre 14 y 18 años de edad" (PDF) (in Spanish). 2013-01-07. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-04-17. Retrieved 2015-02-17.

- Crabtree 2002, p. 67.

- "Our Work – Amnesty International USA". amnestyusa.org. Archived from the original on 8 April 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- Amnesty International 2009, p. 40.

- Amnesty International 2009, p. 41.

- "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Archived from the original on 21 December 2014. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- OECD 2010, p. 129.

- Warrick, Catherine. (2009). Law in the service of legitimacy: Gender and politics in Jordan. Farnham, Surrey, England; Burlington, Vt.: Ashgate Pub. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-7546-7587-7.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2015-02-17.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Peru: Domestic violence, state protection and support services available (March 2007-March 2010) : Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Ottawa" (PDF). 2014-04-14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-04-14. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- Caulfield, Sueann; Chambers, Sarah; Putnam, Lara (2005). Honor, Status, and Law in Modern America. Duke University Press. pp. 38–39.

- Crabtree 2002, p. 10.

- Crabtree 2002, p. 44.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-02-17. Retrieved 2015-02-17.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Cabitza, Mattia (12 September 2011). "Peru leads the way for Latin America's indigenous communities - Mattia Cabitza". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 18 April 2018. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- Crabtree 2002, p. 33.

- "Women, Political Parties and Electoral Reform in Peru | Peru | International IDEA". Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2015-02-17.

- "Women in Parliaments: World Classification". www.ipu.org. Archived from the original on 28 March 2014. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- Bibliography

- Amnesty International (2009). Fatal Flaws: Barriers to Maternal Health in Peru (PDF). London: Amnesty International Publications. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-10-08. Retrieved 2017-10-31.

- Barrett, Pam (2002). Peru. Insight Guides: South America series. Singapore: APA Publications. ISBN 978-1-58573-296-8. Archived from the original on 2016-04-27. Retrieved 2015-08-13.

- Crabtree, John (2002). Peru. Oxford: Oxfam. ISBN 978-0-85598-482-3. Archived from the original on 2016-05-15. Retrieved 2015-08-13.

- OECD (2010). Atlas of Gender and Development : How Social Norms Affect Gender Equality in non-OECD Countries. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Development Centre. ISBN 978-92-64-07520-7.