Sex differences in education

Sex differences in education are a type of sex discrimination in the education system affecting both men and women during and after their educational experiences.[1] Men are more likely to be literate on a global average, although higher literacy scores for women are prevalent in many countries.[2] Women are more likely to achieve a tertiary education degree compared to men of the same age. Men tended to receive more education than women in the past, but the gender gap in education has reversed in recent decades in most Western countries and many non-Western countries.[3]

| Part of a series on |

| Sex differences in humans |

|---|

| Biology |

| Medicine and Health |

| Neuroscience and Psychology |

| Sociology |

Gender differences in school enrollment

This is measured with the Gender Parity Index. The closer to one, the closer to gender equality. When the number is below 1, there are more males than females, and when the number is above 1, there are more females than males.[4]

Primary

| Country | Gender Parity Index[5] |

|---|---|

| Australia | 1 |

| Canada | 0.99 |

| China | 1.01 |

| France | 0.99 |

| Germany | 1.01 |

| Hungary | 0.98 |

| Japan | 1 |

| New Zealand | 1 |

| Mexico | 1.01 |

| Sweden | 1.05 |

| Ukraine | 1.02 |

| United Arab Emirates | 1.01 |

| United States | 1 |

Secondary

| Country | Gender Parity Index[6] |

|---|---|

| Australia | 0.96 |

| Canada | 1.01 |

| China | 1 |

| France | 1 |

| Germany | 0.95 |

| Hungary | 0.99 |

| Japan | 1 |

| New Zealand | 1.05 |

| Mexico | 1.1 |

| Sweden | 1.08 |

| Ukraine | 0.98 |

| United Arab Emirates | 1.01 |

| United States | 0.98 |

Tertiary

| Country | Gender Parity Index[7] |

|---|---|

| Australia | 1.28 |

| Canada | 1.25 |

| China | 1.15 |

| France | 1.22 |

| Germany | 1.05 |

| Hungary | 1.19 |

| Japan | 0.97 |

| New Zealand | 1.35 |

| Mexico | 1.08 |

| Sweden | 1.38 |

| Ukraine | 1.13 |

| United Arab Emirates | 1.3 |

| United States | 1.29 |

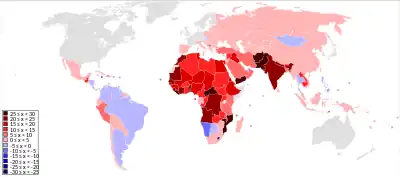

Inequalities in education around the world

Gender based inequalities in education around the world, according to UNESCO, are mainly determined by poverty, geographical isolation, minority status, disability, early marriage, pregnancy and gender-based violence.[8] In the rest of the world, more boys remain out of school than girls, however, women make up two-thirds of the 750 million adults without basic literacy skills.[8]

Developed countries

In various developed countries, there has been an increase in education access for women in the last several decades. In developed countries, girls and boys are enrolled in elementary/kindergarten and middle schools at an equal rate in the educational schooling system. In European nations, girl students tend to flourish more often in secondary school than boys in developed countries, according to Sutherland. African and Asian countries have aided and catered to girls by enforcing certain quotas and scholarships to place themselves in higher education to provide opportunities for better education with long-lasting jobs. The outlook and position of women in higher education have improved drastically over the recent years in various countries around the world. In selective countries, the author claimed that women are being misrepresented and unfairly evaluated at the university level of education. Additionally, in some developed countries, women are persistently a “distinct minority” in higher education according to the article. There is a consistent trend in university-level education on how women make up a small proportion of these schools across certain nations. The other frequent struggles that result in these issues stem from women remaining in a small categorical group of not acquiring doctorate degrees and some postgraduate degrees in various countries.[9]

Other factors based on gender differences in education coherently connect to Aleksandra M. Rogowska and her colleague's study of examining and exploring five traits, academic motivation, personality, and gender in a cross-cultural context. She conducted a study of Polish and Ukrainian college students (424 students) in the physical education sectors. The study required an Item pool test that examined the GPA (Grade Point Average), Academic Motivation scale (AMS), and the model of personality to collect data. Rogowska's study revealed that gender differences were found in “personality traits and academic motivation scales.” The study also showed how notable gender was and prominent as a “moderator” in the dynamic correlation between conscientiousness and academic achievement. The author noted how gender was integral as a third variable to show the connection between conscientiousness and academic accomplishment. Rogowska's study emerged compelling information regarding the motivation factor of women being more motivated than men based on academic achievement.[10]

United States

A study looking at children born in the 1980s in the United States until their adulthood found that boys with behavioural problems were less likely to complete high school and university than girls with the same behavioural problems. Boys had more exposure to negative experiences and peer pressure, and had higher rates of grade repetition. Owens, who conducted the study, attributes this to negative stereotypes about boys and says that this may partially explain the gender gap in education.[11]

Science, technologies, engineering, and mathematics

In developed countries, women are often underrepresented in science, technologies, engineering, and mathematics (STEM).[12] According to the OECD, 71% of men who graduate with a science degree work as professionals in physics, mathematics and engineering, whereas only 43% women work as professionals. "Fewer than 1 in 3 engineering graduates, and fewer than 1 in 5 computer science graduates are female".[13]

Regarding the issue of gender and education in the STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) field, and how women in STEM have underwhelming sparse numbers in the field which is alarming for policymakers and sociology scientists. The authors Stoet and Geary, utilized an international database of student success in the STEM field and mentioned and analyzed how girls performed comparably to boys in various countries in the science field. Analytically, girl students emerged as more than capable of performing at prominent levels in STEM at a university level. Furthermore, the analysis acknowledged how girls performed comparably to boys and higher in multiple countries in specific subjects corresponding to math and science. Stoet and Geary mentioned how the relative academic strengths regarding sex differences, and the demand for STEM degrees increased with a rise in gender equality on a national scale in different countries. In addition, mediation analysis showed that “life quality pressures in less gender-equal" nations encourage and advocate for women's involvement in STEM education. Overall, the author mentions that there is intense pressure for less-gender-equal countries to create a surge in the advocation of women's participation in STEM subjects.[14]

Centering the problems of gender education in the STEM field around gender-based bias evaluations of children relating to anxiety and lack of representation of women. Author Drew H. Bailey mentions how regardless of worldwide striving and progress for gender equality across different societies, the lack of women in STEM programs is a reoccurring issue in educational institutions. Furthermore, Bailey and his colleagues studied how the possibility that the gender difference in STEM subjects' anxiety holds a contribution to the underrepresentation of women. The study involved assessing the number of predictions from the “gender stratification model,” which evaluates “cross-national patterns” of gender distinctions in math anxiety and performance. The study tailored itself to the number of outcomes of gender inequality on a national scale that related to math anxiety and performance in education. The analytical data collected from the PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) of which 761,655 students from 68 nations participated was measured to further the study. The results of the study showed that countries with more gender-egalitarian, and economically advanced societies have a moderate level of mathematics anxiety. There are comparatively more “mothers in STEM fields” in developed countries; however, according to the study they treasured “mathematical competence” in their sons more than their daughters. The mothers in STEM fields cherished their sons to have more capability in math than their daughters according to the author's study. However, the worldwide average in STEM exams is closer in proximity in terms of performance between girls and boys, according to Baily and his colleagues.[15]

Second sexism in education

Discrimination against men in education is sometimes known as "second sexism". Second sexism has not seen significant backing or research even among those who study discrimination.[16] Second sexism in education, together with obvious sexrole stereotypes, make male students face more punishment in school than female students.[17]

Grading Bias in Schools Against Boys

In the past, men tended to get more education than women, however, the gender bias in education gradually turned to men in recent decades. In recent years, teachers have had modest expectations for boys' academic performance. The boys were labeled as reliant, the impression teachers provide students can affect the grade they receive. At schools or colleges, prejudice against male students is common. Usually, teachers happened to have a better perception of girls than boys. Many teachers have a poorer relationship with boys than girls because they relate to girls more deeply than they do with boys. Due to this bias in grading, male students are more likely than female students to obtain worse grades. Some recent studies indicate that discrimination against boys in grading may contribute to some of this gender disparity. Studies have shown that teachers typically have lower expectations of boys' academic performance and behavior in school, even though most teachers aim to be fair and work to provide equitable learning opportunities for all kids.[18][19][20][21] In Ingela Åhslund and Lena Boström's study, they've discovered that girls are seen as autonomous, driven, and high achievers, whereas boys are seen as troublemakers and underachievers.[22] Moreover, Ingela and Lena found out that gender stereotypes cause differing interpretations of the same behavior in boys and girls, with girls being perceived as independent and having stronger communication and organizational skills and boys being seen as unprepared, unmotivated, and infantile, according to studies on gender attribution.

Grading Bias Against Boys on Different Subjects

In a research conducted by Camille Terrier, she discovered that in both arithmetic and French, teachers' gender bias significantly and highly affects how far boys advance relative to girls.[23] This is the first study to examine gender differences in elementary school performance using objective and subjective performance through scientific data. Even in subjects like math and science, where their test scores were either equal to or lower than the girls' test scores, the study found that boys received worse marks than girls. In middle school, the gender bias of teachers toward males accounts for 6% of the math achievement gap between boys and girls. Moreover, she gathered data from schools in a fairly underdeveloped educational region of France. According to the research, inexperienced instructors tend to be more biased toward boys in the classroom. Teachers assigned to underprivileged areas are frequently younger than those working in institutions with greater privileges. Her study established that gender biases among teachers will significantly affect the success gap between boys and girls in different subjects. This explains why boys are falling further behind girls in academic performance.

Teachers’ Gender Biases Affect Male Students’ Achievement

Girls perform better in school than boys do in the majority of Western nations. Due to their poorer grades, boys have a decreased probability of getting admitted into further education, which may ultimately limit their chances of success in the job market. A study conducted by Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development proved that boys are gradually falling behind girls in schools. Boys who fall behind risk dropping out of school, failing to enroll in college or university, or finding themselves unemployed as a result of this disadvantage. In OECD nations, 66% of women and 52% of men, respectively, entered university programs in 2009, and this disparity is widening.[24] In 2015, 43% of women in Europe between the ages of 30-34 completed higher education, as opposed to 34% of men in the same age bracket. There is considerable interest in figuring out the causes of this disparity because it has grown by 4.4 percentage points over the past ten years. Moreover, male students are at a larger risk of experiencing academic, social, and emotional challenges, which can lead to a greater sense of alienation from oneself and society, according to current research on gender disparities in educational settings at all socioeconomic levels.

Possible Solutions and Implementations

According to Björn Tyrefors Hinnerich, Erik Höglin, and Magnus Johannesson's research,[25] they proved that girls perform better in school than boys has been found in numerous studies. It's critical to keep researching the causes of this gender difference. The most likely explanation is that girls put in more effort in school because this difference does not seem to be the result of discrimination and is unlikely to depend on innate differences in ability.[26][27][28][29] Designing measures to close the gender gap in education requires research into why this is the case and how it differs with different learning contexts. The diverse learning styles used by boys and girls in the classroom must be understood by the school.[22] Boys may be viewed as restless, lazy, and less driven when instruction is not appropriately tailored to their needs. Given the notion that equal circumstances should be established in the classroom, it is important to explore gender inequalities and boys' inferior performance without bias. Instead of focusing on the behavior and performance of their pupils, teachers must be prepared to critically analyze and problematize their own teaching. In order to create inclusive environments for all students, boys and girls alike, it is also crucial that the approach and methods are modified to match the criteria of an equal school, depending on the school's compensating tasks.

Gender differences in education based on teacher's gender

Gender discrimination in education exists as well from differential treatment students receive by either male or female teachers. In Newfoundland, Jim Duffy et al. found out that teachers may have higher expectations for boys in math and science, and for girls; higher expectations in language. Teachers were found to also have a tendency to praise students matching gender expected norms. Students were praised more often by female mathematics teachers than female literature teachers, but praise was more often given by male literature teachers occurred than by male mathematics teachers. Criticism has also been found to be directed toward male students significantly more often than female students in both literature, and mathematics classes, regardless of teacher's gender.[30] Altermatt suggested however that a greater number of teacher-student interactions may be directed at boys as a result of boy students initiating more interaction.[31]

In a study done by Paulette B. Taylor, video tapes depicting the same inappropriate behavior (pencil tapping, disturbing others, and mild rebukes to the teacher) of 4 different students; An African American male and female, and a white male and female. 87 inservice teachers, and 99 preservice teachers viewed the tapes, which were also broken down into African American male and female groups, as well as white male and female teacher-participant groups. Participants were then asked to complete a 32 item behavior rating scale focusing on individual teacher perceptions of students in video tape. Analysis revealed statistical significance in differences related to the gender of the teacher to perception of the African American female student being viewed as most troublesome. However, no statistical significance was found in students ratings in relation to ethnic backgrounds of the teachers, or interaction of ethnicity and gender. Male teachers rated students higher on impulsivity than female teachers in general, however the only statistically significant find was in the rating of African American female students of all participant groups.[32]

Forms of sex discrimination in education

Sex discrimination in education is applied to women in several ways. First, many sociologists of education view the educational system as an institution of social and cultural reproduction.[33] The existing patterns of inequality, especially for gender inequality, are reproduced within schools through formal and informal processes.[1] In Western societies, these processes can be traced all the way back to preschool and elementary school learning stages. Research such as May Ling Halim et al.'s 2013 study has shown that children are aware of gender role stereotypes from a young age, with those who are exposed to higher levels of media, as well as gender stereotyped behavior from adults holding the strongest perception of gender stereotypical roles, regardless of ethnicity.[34] Indeed, Sandra Bem's gender schema theory identifies that children absorb gender stereotypes by observing the behavior of humans around them and then imitate the actions of those they deem to be of their own gender.[35] Thus, if children attain gender cues from environmental stimuli, it stands to reason that the early years of a child's education are some of the most formative for developing ideas about gender identity and can potentially be responsible for reinforcing harmful notions of disparity in the roles of males and females. Jenny Rodgers identifies that gender stereotypes exist in a number of forms in the primary classroom, including the generalization of attainment levels based upon sex and teacher attitudes towards gender appropriate play.[36]

Hidden curriculum

In her 1978 quantitative study, Katherine Clarricoates conducted field observations and interviews with British primary school teachers from a range of schools located in both rural and urban and wealthy and less wealthy areas.[37] Her study confirms that Rodgers' assertions about gender stereotypes and discrimination were widely seen in the classrooms. In an extract from one of the interviews, a teacher claimed that it is "subjects like geography…where the lads do come out…they have got the facts whereas the girls tend to be a bit more woollier in most of the things". [38] Meanwhile, other teachers claimed that "they (girls) haven't got the imagination that most of the lads have got" and that "I find you can spark the boys a bit easier than you can the girls…Girls have got their own set ideas – it's always '…and we went home for tea'… Whereas you can get the boys to write something really interesting…". [38] In another interview, a teacher perceived gender behavioral differences, remarking "…the girls seem to be typically feminine whilst the boys seem to be typically male…you know, more aggressive... the ideal of what males ought to be", [39] while another categorized boys as more "aggressive, more adventurous than girls". [40] When considering Bem's gender schema theory in relation to these statements, it is not difficult to see how male and female pupils may pick up various behavioral cues from their teachers' gender differentiation and generalizations which then manifest themselves in gendered educational interests and levels of attainment. Clarricoates terms this bias the "hidden curriculum" as it is deviant from the official curriculum which does not discriminate based on gender. [41] She notes that it arises from a teacher's own underlying beliefs about gendered behavior and causes them to act in favor of the boys but to the detriment of the girl pupils. This ultimately leads to the unfolding of a self-fulfilling prophecy in the academic and behavioral performances of the students.[42] Citing Patricia Pivnick's 1974 dissertation on American primary schools, Clarricoates posits that

- It is possible that by using a harsher tone for controlling the behavior of boys than for girls, the teachers actually foster the independent and defiant spirit which is considered 'masculine' in our culture…At the same time, the 'femininity' which the teachers reinforced in girls may foster the narcissism and passivity which results in lack of motivation and achievement in girls.[43]

This analysis highlights the lifelong hindrances that the "hidden curriculum" of teachers can inflict on both genders.

Linguistic sexism

Another element of the "hidden curriculum" Clarricoates identifies is linguistic sexism. She defines this term as the consistent and unconscious use of words and grammatical forms by teachers that denigrate women and emphasize the assumed superiority of men, not only in lesson content but also in situations of disciplinary procedure. [40] One example of this she cites is the gendering of animal and inanimate characters. She states that teachers, together with TV presenters and characters as well as curricular materials all refer to dinosaurs, pandas, squirrels and mathematical characters as "he", conveying to young children that these animals all only come in the male gender. Meanwhile, only motherly figures such as ladybirds, cows and hens are referred to as "she". As a result, school books, media and curriculum content all give students the impression that females do not create history which contributes to the damaging assumption that females cannot transform the world, whereas men can. [40]

In addition, Clarricoates discusses the linguistic sexism inherent to the adjective choice of teachers when admonishing or rewarding their pupils. She notes that "if boys get out of hand they are regarded as 'boisterous', 'rough', 'assertive', 'rowdy' and 'adventurous'", whereas girls were referred to as "'fussy', 'bitchy', giggly', 'catty' and 'silly'". According to Clarricoates' previously stated observations, the terms applied to boys imply positive masculine behavior, meanwhile the categories used for girls are more derogatory.[40] This difference in teachers' reactions to similar behaviors can again be seen as contributing to the development of gender stereotyped behaviors in young pupils. Another element of linguistic sexism that Clarricoates identifies is the difference in the treatment of male and female pupils' use of "improper language" by their teachers; girls tended to be censured more harshly compared to boys, due to unconscious biases about gender appropriate behavior. While girls were deemed as "unladylike" for using "rough" speech, the same speech uttered by their male counterparts was regarded as a part of normal masculine behavior, and they were thus admonished less harshly. This creates a linguistic double standard which can again be seen to contribute to long-term gender disparities in behavior. [40]

Clarricoates concludes her study by observing that there is a "catch 22" situation for young female pupils. If a girl conforms to institutional ideals by learning her lessons well, speaking appropriately and not bothering the teacher then her success is downplayed in comparison to the equivalent behavior in a male pupil. Indeed, she is regarded as "passive", or a "goody-goody" and as "lesser" than her male pupils. As a result, this reinforcement will foster submissiveness and self-depreciation; qualities which society does not hold in great esteem. However, if she does not conform then she will be admonished more harshly than her equivalent male pupils and also be viewed in a more negative light. She will be regarded as problematic and disruptive to the class, which may ultimately impact her academic performance and career prospects in the future. Furthermore, if she is able to survive the school institution as an assertive and confident individual then she will still face many challenges in the workplace, where these characteristics in women are often perceived as "bossy" or "overbearing". [44]

Dominance of heteronormativity

Rodgers identifies that another challenge to gender equality in the elementary school classroom is the dominance of heteronormativity and heterosexual stereotypes. Citing the research of Guasp, she maintains that heteronormative discourse still remains the norm, both in schools and in wider western society.[45][46] She notes that gender and heterosexual stereotypes are intrinsically linked, due to expectations of females being sexually attracted to males and vice versa, as part of their gender performance. Thus, one of the major challenges to gender equality is the concealment of sexual diversity under the dominance of heteronormativity. [47] Rodgers identifies that although the 1988 Education Reform Act in the United Kingdom helped to increase opportunities for gender diversity by ensuring that both sexes study the same core subjects, on the other hand, heterosexual stereotyping was exacerbated by the passing of Section 28 of the 1988 Local Government Act, which decreed homosexuality "as a pretended family relationship." This caused a significant hindrance in the widespread acceptance of homosexuality and thus, the progression of gender equality in schools. [48] Despite the 2003 repeal of this act, [49] the pupils most at risk of discrimination as a result of gender biases in the "hidden curriculum", are still those who do not conform to gender and heterosexual stereotypes. Indeed, Rodgers cites these teaching approaches as conforming to hegemonic masculinity, and attributes this method to the marginalization of students who do not conform to their stereotypical gender roles. [48]

Another way the educational system discriminates towards females is through course-taking, especially in high school. This is important because course-taking represents a large gender gap in what courses males and females take, which leads to different educational and occupational paths between males and females. For example, females tend to take fewer advanced mathematical and scientific courses, thus leading them to be ill-equipped to pursue these careers in higher education. This can further be seen in technology and computer courses.[1]

Cultural norms may also be a factor causing sex discrimination in education. For example, society suggests that women should be mothers and responsible for the bulk of child rearing. Therefore, women feel compelled to pursue educational pathways that lead to occupations that allow for long leaves of absence, so they can be stay-at-home mothers.[1] Child marriages can be another determining factor in ending the formal education and literacy rates of women in various parts of the world.[50] According to research conducted by UNICEF in 2013, one out of three girls across the developing world is married before the age of 18.[51] As an accepted practice in many cultures, the investment in a girl's education is given little importance, whereas emphasis is placed on men and boys to be the 'breadwinners.'[52]

A hidden curriculum may further add to discrimination in the educational system. Hidden curriculum is the idea that race, class, and gender have an influence on the lessons that are taught in schools.[53] Moreover, it is the idea that certain values and norms are instilled through curriculum. For example, U.S. history often emphasizes the significant roles that white males played in the development of the country. Some curriculum have even been rewritten to highlight the roles played by white males. An example of this would be the way wars are talked about. Curricula on the Civil War, for instance, tend to emphasize the key players as Ulysses S. Grant, Robert E. Lee, and Abraham Lincoln. Whereas woman or men of color such as Harriet Tubman as a spy for the Union, Harriet Beecher Stowe or Frederick Douglass, are downplayed from their part in the war.[54] Another part is that the topics being taught are masculine or feminine. Shop classes and advanced sciences are seen as more masculine, whereas home economics, art, or humanities are seen as more feminine. The problem comes when students receive different treatment and education because of his or her gender or race.[54] Students may also be socialized for their expected adult roles through the correspondence principle laid out by sociologists including Samuel Bowles and Herbert Gintis. Girls may be encouraged to learn skills valued in female-dominated fields, while boys might learn leadership skills for male-dominated occupations. For example, as they move into the secondary and post-secondary phases of their education, boys tend to gravitate more toward STEM courses than their female classmates.[55]

Differential treatment in parental involvement

Child development in educational areas can also be influenced by the treatment a child receives from his/her parents. In a study by Rebecca Carter, of which private and public school 8th graders were looked at using the National Education Longitudinal Study (NELS), a study which provides many details regarding parental involvement in their child's educational attainment.[56] The data found that females engaged in school discussion with their parents more frequently than male counterparts, however when controlling for test scores, grades, and educational aspirations there was a reduction in magnitude of the gender effect of school discussions, but still maintaining its significance. Its also been found that parents are more involved with school on behalf of their sons, but involvement was not known to be purely academic, or for behavioral/non-academic reasons. There was also no difference found in time limits placed on watching television between males/females after school. However, it was noted that females were more likely than males to have less time spent socializing with friends based on parental involvement, reflecting the concept that parents put forth greater efforts to protect their daughters. Data has also shown that parental attendance at school events is greater for daughters than for sons, and when controlling for academic factors it has been found that over half of the gender differences that had been found were explained by academic factors, meaning that parental involvement in these events were influenced by daughter's academic performance.[56]

Gender discrimination in education also exist from household discrimination. Parents may spend differently based on gender of their children which is an unequal treatment. Shaleen Khanal studied the expenditure people spent on girls and boys in Nepal. Based on his research, he found that parents spend in education expenditure, compared to boys, is 20% less on girls which is very unequal.[57] The expenditure difference including spending unequally on students' fee, textbooks, school supplies like school bags, uniforms and other education expenditure.[57] And this kind of discrimination is rising in Nepal. Also, parents in Nepal are more willing to spend more money in order to let boys to go to private school for the better education. This phenomenon is more pronounced in Nepal' s rural area, but it happened in urban areas as well.[57]

Women's scholarships

In a study of 220 universities in the United States, 84% of them offered single-gender scholarships. The study assessed whether these universities were discriminatory if there are 4 or more women-only scholarships compared to men-only, and described 68.5% as discriminatory against men.[58] In many universities there are scholarships for women only. These have been described as illegal under Title IX and discriminatory against men, causing the United States Department of Education to launch multiple investigations around the country.[59] People pushing to get these removed have mentioned that these scholarships were created in the 1970s when women were under-represented in tertiary education, but it is now men who underperform and that the scholarships should become gender-neutral.[60][61] In 2008 in New Zealand, the Human Rights Commission considered abolishing women's scholarships.[62]

Consequences of sex discrimination in education

Discrimination results for the most part, being in low status, sex-stereotyped occupations, which in part is due to gender differences in majors.[63] They also have to endure the main responsibilities of domestic tasks, even though their labor force participation has increased. Sex discrimination in high school and college course-taking also results in women not being prepared or qualified to pursue more prestigious, high paying occupations. Sex discrimination in education also results in women being more passive, quiet, and less assertive, due to the effects of the hidden curriculum.[1]

Classroom interactions can also have unseen consequences. Because gender is something we learn, day-to-day interactions shape our understandings of how to do gender.[53] Teachers and staff in an elementary may reinforce certain gender roles without thinking. Their communicative interactions may also single out other students. For example, a teacher may call on one or two students more than the others. This causes those who are called on less to be less confident. A gendered example would be a teacher expecting a girl to be good at coloring or a boy to be good at building. These types of interactions restrict a student to the particular role assigned to them.[54]

Other consequences come in the form of what is communicated as appropriate behaviors for boys and girls in classes like physical education. While a teacher may not purposely try to communicate these differences, they may tend to make comments based on gender physical ability.[64] For example, a male may be told that he throws like a girl which perpetuates him to become more masculine and use brute force. A female, on the other hand, might be told she is too masculine looking, causing her to become more reserved and less motivated.[65]

Some gender discrimination, whether intentional or not, also effects the positions students may strive for in the future. Females may not find interest in science, technology, engineering, or math (STEM), because they have not been exposed to those types of classes. This is because interactions within the school and society are pushing them towards easier, more feminine classes, such as home economics or art. They also might not see many other women going into the STEM field. This then lowers the number of women in STEM, further producing and continuing this cycle.[66] This also has a similar effect on males. Because of interactions from teachers, such as saying boys do not usually cook, males may then be less likely to follow careers such as a chef, an artist, or a writer.[65]

Gender gap in literacy

The latest national test scores in the United States, collected by the NAEP assessment, show that girls have met or exceeded the reading performance of boys at all age levels. The literacy gap in fourth grade is equivalent to males being two years behind the average girl in reading and writing. At the middle school level, statistics from the Educational Testing Service show that the gap between eight-grade males and females is more than six times greater than the differences in mathematical reasoning, mathematical reasoning favoring males. These findings have spanned across the globe as the International Association for Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA) found gender to be the most powerful predictor of performance in a study of 14 countries.[67]

Booth, Johns, and Bruce state that at both national and international levels "male students do not do as well as girls in reading and writing and appear more often in special education classes, dropout rates and are less likely to go to university".[68][69] Boys face a multitude of difficulties when it comes to literacy and the article lists some of the possible areas of literacy education where these difficulties could stem from. These include, but are not limited to, their own gender identity, social and cultural issues, religion, technology, school cultures, teaching styles, curriculum, and the failures of pre-service and in-service teaching courses.[1]

It is also important to consider two aspects of boys and literacy education as raised in the Booth article, which draws from the 2002 work of Smith and Wilhelm. The first is achievement; boys typically take longer to learn than girls do, although they excel over girls when it comes to "information retrieval and work-related literacy tasks".[70] It is important, therefore, for the teacher to provide the appropriate activities to highlight boys' strengths in literacy and properly support their weaknesses. Also, boys tend to read less than girls in their free time. This could play a role in the fact that girls typically "comprehend narrative and expository texts better than boys do".[70] In his 2009 book Grown Up Digital, Tapscott writes that there are other methods to consider in order to reach boys when it comes to literacy: "Boys tend to be able to read visual images better... study from California State University (Hayword) saw test scores increase by 11 to 16% when teaching methods were changed to incorporate more images".[71] Smith and Wilhelm say that boys typically have a "lower estimation of their reading abilities" than girls do.[70]

Possible solutions and implementation

One attempted change made to literacy instruction has been the offering of choice in classroom gender populations. In Hamilton, Ontario, Cecil B. Stirling Elementary/Junior School offered students in grades 7 and 8, and their parents, a choice between enrolling in a boys-only, girls-only or co-ed literacy course. Single-gender classes were most popular, and although no specific studies have shown a statistical advantage to single-gender literacy classes, the overall reaction by boys was positive: "I like that there's no girls and you can't be distracted. [. . .] You get better marks and you can concentrate more."[72] However, a 2014 meta-analysis based on 84 studies representing the testing of 1.6 million students in Grades K-12 from 21 nations published in the journal of Psychological Bulletin, found no evidence that the view single sex schooling is beneficial over co-gendered schools.[73]

With boys-only classrooms not always being possible, it then becomes the responsibility of the literacy instructor to broaden the definition of literacy from fiction-rich- literacy programs to expose students to a variety of texts including factual and non-fiction texts (magazines, informational texts, etc.) that boys are already often reading; provide interest and choice in literacy instruction; expand literacy teaching styles to more hands-on, interactive and problem-solving learning, appealing to a boy's strengths; and to provide a supportive classroom environment, sensitive to the individual learning pace of each boy and providing of a sense of competence.[67]

Other everyday practices that attempt to "close the gender gap" of literacy in the classroom can include:[74]

- Tapping into visual-spatial strengths of boys. (Filmstrips/Comics)

- Using hands-on materials. (Websites, handouts)

- Incorporating technology. (Computer Learning Games, Cyberhunts)

- Allowing time for movement. (Reader's Theaters and plays, "Active" Mnemonics)

- Allowing opportunities for competition. (Spelling Bees, Jeopardy, Hangman)

- Choosing books that appeal to boys. ("Boy's Rack" in Classroom Library)

- Providing male role models. (High-school Boys Tutoring Younger Boys in Reading, Reading/Speaking Guests)

- Boys-only reading programs. (Boys-only Book Club)

Homeschooled children

A study by the HSLDA showed that the achievement gender divide for home-schooled children was less that of public schools. Homeschooled boys (87th percentile) and girls (88th percentile) scored equally well. The income of the parents did not have much impact on the results, however, a major factor in student achievement is whether a parent had attained a tertiary education.[75]

Sex differences in tertiary education

A 2014 meta-analysis of sex differences in scholastic achievement published in the journal of Psychological Bulletin found females outperformed males in teacher-assigned school marks throughout elementary, junior/middle, high school and at both undergraduate and graduate university level.[76] The meta-analysis done by researchers Daniel Voyer and Susan D. Voyerwas from the University of New Brunswick drew from 97 years of 502 effect sizes and 369 samples stemming from the year 1914 to 2011, and found that the magnitude of higher female performance was not affected by year of publication, thereby contradicted recent claims of "boy crisis" in school achievement.[76] Another 2015 study by researchers Gijsbert Stoet and David C. Geary from the journal of Intelligence found that girl's overall education achievement is better in 70 percent of all the 47–75 countries that participated in PISA.[77] The study consisting of 1.5 million 15-year-olds found higher overall female achievement across reading, mathematics, and science literacy and better performance across 70% of participating countries, including many with considerable gaps in economic and political equality, and they fell behind in only 4% of countries.[77] In summary, Stoet and Geary said that sex differences in educational achievement are not reliably linked to gender equality.[77] The results do not prove, however, greater intelligence of women in relation to men.

Data from the United States Department of Education shows that 64.5% of students entering for a four-year bachelor's degree had graduated within six years. Women had a graduation rate that higher than men by 6.9 points. 66.4% of women entering the degree achieved it within 6 years, compared to 60.4% for men.[78] In OECD countries, women are more likely to hold a university degree than men of the same age. The proportion of women aged 25–34 who have a university degree is 20 percentage points higher than men of the same age.[79]

In 2005, USA Today reported that the "college gender gap" was widening, stating that 57% of U.S. college students are female.[80] This gap has been gradually widening, and as of 2014, almost 45% of women had a bachelor's degree, compared to 32% of men with a bachelor's degree.[81]

Since the 1990s, enrollment on university campuses across Canada has risen significantly. Most notable is the soaring rates of female participants, which has surpassed the enrollment and participation rates of their male counterparts.[82] Even in the United States, there is a significant difference in the male to female ratio in campuses across the country, where the 2005 averages saw male to female university participants at 43 to 57.[83] Although it is important to note that the rates of both sexes participating in post-secondary studies is increasing, it is equally important to question why female rates are increasing more rapidly than male participation rates. Christofides, Hoy, and Yang study the 15% male to female gap in Canadian universities with the idea of the University Premium.[82] In 2007, Drolet argues in 2007, that this phenomenon is caused by "A university degree ha[ving] a greater payback for women relative to what they could have earned if they only had a high-school diploma because men traditionally have had more options for jobs that pay well even without post-secondary education."[84]

Sex discrimination in education globally

Improvements in removing sex discrimination from education have had great advancements in the last many years all over the world, but discrimination does still happen. Sexist values instilled into children's minds insist that boys do well at sports, be physically strong, and be competitive and that girls should prepare to cater to their husbands while doing things such as cooking, cleaning, and taking care of children. These values also cause bullying in young children to individuals who do not follow the social norms of how girls and boys should act and what interests they should have. On a global scale, many developing countries force females to leave school earlier than men and do not give them the same opportunities.[85]

China

China's gender inequality within their education system dates back centuries, but despite some improvement over time has a long way to go. Huge economic and societal development since the 1980s has become a major factor in improving gender equality in not only their education systems but China as a whole. Since the government has more money to invest in the education system, more schools were built, and more women gained the opportunity to attend school.[86] Despite this, there is still a huge barrier between discrimination in rural versus urban areas. In rural areas, women have consistently been twice as likely to be illiterate when compared to men.[86] On top of this, China's one-child policy, although no longer in effect, made a lasting impact on the discrimination against women by their families as most families hoped to have a son. This so-called "son preference” has prevailed among most Chinese parents for centuries and continues to make women less important.

United States

Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 states that no person should be excluded, denied benefits, or discriminated against based on sex in schools and federally funded activities in the United States.[87] This covers a wide variety of places such as, but not limited to schools, local and state agencies, charters, for-profits, libraries, museums, and vocational rehabilitation agencies in all 50 states as well as territories of the United States. Despite being initially geared towards protecting women, Title IX covers the discrimination of all people based on sex, including LGBTQI+ students. Prior to Title IX being passed many women were denied access to education or participation in extracurricular activities such as sports or male dominant clubs.[88] The Office of Credit Ratings, or the OCR for short, ensures federally funded or assisted organizations follow Title IX by evaluating, investigating, and collecting allegations of sex discrimination.[89] Although Title IX was a great step in the right direction in battling sex discrimination in education in the United States, many people are still discriminated against today.

Sub-Saharan Africa

In most Sub-Saharan countries gender gaps increased during the colonial era and after gaining independence most began to decline. Africa had a small initial educational gender gap, but little progress has been made to close it. Sub-Saharan Africa holds twelve out of 17 countries in the world that have not yet reached equality in education.[90] Gender gaps are smaller in southern Africa because there are more accessible areas near railroads or on the coast, but the biggest problem for these countries is the way schools are preparing their students. Colleges in Africa have not diversified their systems of education or expanded the level of skills taught in order to prepare them for the demands of labor.[90] Another large problem facing African women is the vast amount of arranged marriages at a young age. As a direct result of this many young women are forced to drop out of school to care for the needs of their husbands and children.[91] In order to correct many of these issues, governments must address the need for better education and appropriate skills training to help battle the rising unemployment rate.

See also

References

- Pearson, Jennifer. "Gender, Education and." Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology. Ritzer, George (ed). Blackwell Publishing, 2007. Blackwell Reference Online. 31 March 2008 <http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/tocnode?id=g9781405124331_chunk_g978140512433113_ss1-16>

- Davies, Bronwyn (2007). "Gender economies: literacy and the gendered production of neo-liberal subjectivities". Gender and Education. 19 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1080/09540250601087710. S2CID 143595893.

- Van Bavel, Jan; Schwartz, Christine R.; Esteve, Albert (16 May 2018). "The Reversal of the Gender Gap in Education and its Consequences for Family Life". Annual Review of Sociology. 44 (1): 341–360. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-073117-041215. ISSN 0360-0572. S2CID 13717944.

- "unstats | Millennium Indicators". unstats.un.org. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- "School enrollment, gender parity index". World Bank Gender Data Portal. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- "School enrollment, gender parity index". World Bank Gender Data Portal. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- "School enrollment, gender parity index". World Bank Gender Data Portal. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- "Education and gender equality". UNESCO. 25 April 2013. Archived from the original on 16 October 2018. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- Sutherland, Margaret B. (January 1987). "Sex Differences in Education: an overview". Comparative Education. 23 (1): 5–9. doi:10.1080/0305006870230102. ISSN 0305-0068.

- Kuśnierz, Cezary; Rogowska, Aleksandra M.; Pavlova, Iuliia (7 August 2020). "Examining Gender Differences, Personality Traits, Academic Performance, and Motivation in Ukrainian and Polish Students of Physical Education: A Cross-Cultural Study". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 17 (16): 5729. doi:10.3390/ijerph17165729. ISSN 1660-4601. PMC 7459791. PMID 32784806.

- Owens, Jayanti (2016). "Early Childhood Behavior Problems and the Gender Gap in Educational Attainment in the United States". Sociology of Education. 89 (3): 236–258. doi:10.1177/0038040716650926. PMC 6208359. PMID 30393398 – via Sagepub.

- "Indicators of Gender Equality in Education – OECD". www.oecd.org. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- "Data – OECD". www.oecd.org. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- Stoet, Gijsbert; Geary, David C. (April 2018). "The Gender-Equality Paradox in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics Education". Psychological Science. 29 (4): 581–593. doi:10.1177/0956797617741719. ISSN 0956-7976. PMID 29442575. S2CID 4874507.

- Stoet, Gijsbert; Bailey, Drew H.; Moore, Alex M.; Geary, David C. (21 April 2016). Windmann, Sabine (ed.). "Countries with Higher Levels of Gender Equality Show Larger National Sex Differences in Mathematics Anxiety and Relatively Lower Parental Mathematics Valuation for Girls". PLOS ONE. 11 (4): e0153857. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1153857S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0153857. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4839696. PMID 27100631.

- Aa, Suzan van der (11 August 2014). "Book review: The second sexism: Discrimination against men and boysBenatarDavidThe second sexism: Discrimination against men and boysChichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012, pbk, ISBN 978-0-470-67451-2, 288 pp". International Review of Victimology. 20 (3): 351–354. doi:10.1177/0269758014533180. ISSN 0269-7580. S2CID 146922475.

- Benatar, David (2003). "The Second Sexism". Social Theory and Practice. 29 (2): 177–210. doi:10.5840/soctheorpract200329213. ISSN 0037-802X. S2CID 50354829.

- Epstein, Debbie; Maw, Janet; Elwood, Jannette; Hey, Valerie (April 1998). "Guest editorial: Boys' "underachievement"". International Journal of Inclusive Education. 2 (2): 91–94. doi:10.1080/1360311980020201. ISSN 1360-3116.

- Frosh, Stephen; Phoenix, Ann; Pattman, Rob (2002), "Boys talk", Young Masculinities, London: Macmillan Education UK, pp. 22–49, doi:10.1007/978-1-4039-1458-3_2, ISBN 978-0-333-77923-1, retrieved 18 October 2022

- Mendick, Heather (March 2007). "Lads and Ladettes in School: Gender and a Fear of Failure By Carolyn Jackson". British Journal of Educational Studies. 55 (1): 96–98. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8527.2007.367_2.x. ISSN 0007-1005. S2CID 144360033.

- Ghaill, Mairtin Mac An (1994), "The Making of Black English Masculinities", Theorizing Masculinities, 2455 Teller Road, Thousand Oaks California 91320 United States: SAGE Publications, Inc., pp. 183–199, doi:10.4135/9781452243627.n10, ISBN 9780803949041, retrieved 18 October 2022

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Åhslund, Ingela; Boström, Lena (26 April 2018). "Teachers' Perceptions of Gender Differences -What about Boys and Girls in the Classroom?". International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research. 17 (4): 28–44. doi:10.26803/ijlter.17.4.2.

- Terrier, Camille (1 August 2020). "Boys lag behind: How teachers' gender biases affect student achievement". Economics of Education Review. 77: 101981. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2020.101981. ISSN 0272-7757. S2CID 46800507.

- "OECD Employment Outlook 2012 (Summary in Estonian)". OECD Employment Outlook. 6 August 2012. doi:10.1787/empl_outlook-2012-sum-et. ISBN 9789264166684. ISSN 1999-1266.

- Hinnerich, Björn Tyrefors; Höglin, Erik; Johannesson, Magnus (1 August 2011). "Are boys discriminated in Swedish high schools?". Economics of Education Review. 30 (4): 682–690. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2011.02.007. hdl:10419/45706. ISSN 0272-7757.

- Feingold, Alan (February 1988). "Cognitive gender differences are disappearing". American Psychologist. 43 (2): 95–103. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.43.2.95. ISSN 1935-990X.

- Guiso, Luigi; Monte, Ferdinando; Sapienza, Paola; Zingales, Luigi (30 May 2008). "Culture, Gender, and Math". Science. 320 (5880): 1164–1165. doi:10.1126/science.1154094. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 18511674. S2CID 2296969.

- Hyde, Janet S.; Fennema, Elizabeth; Lamon, Susan J. (1990). "Gender differences in mathematics performance: A meta-analysis". Psychological Bulletin. 107 (2): 139–155. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.139. ISSN 1939-1455. PMID 2138794.

- Hyde, Janet S.; Lindberg, Sara M.; Linn, Marcia C.; Ellis, Amy B.; Williams, Caroline C. (25 July 2008). "Gender Similarities Characterize Math Performance". Science. 321 (5888): 494–495. doi:10.1126/science.1160364. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 18653867. S2CID 28135226.

- Duffy, Jim (2001). "Classroom Interactions: Gender of Teacher, Gender of Student, and Classroom Subject". Sex Roles. 45 (9/10): 579–593. doi:10.1023/A:1014892408105. S2CID 145366257.

- Altermatt, Ellen Rydell; Jovanovic, Jasna; Perry, Michelle (1998). "Bias or responsivity? Sex and achievement-level effects on teachers' classroom questioning practices". Journal of Educational Psychology. 90 (3): 516–527. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.90.3.516. ISSN 0022-0663.

- Taylor, Paulette B.; Gunter, Philip L.; Slate, John R. (February 2001). "Teachers' Perceptions of Inappropriate Student Behavior as a Function of Teachers' and Students' Gender and Ethnic Background". Behavioral Disorders. 26 (2): 146–151. doi:10.1177/019874290102600206. ISSN 0198-7429. S2CID 143312322.

- Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J. C. (1990). Reproduction in education, society and culture (Vol. 4). Sage.

- Halim, May Ling (2013). "Four-year-olds' Beliefs About How Others Regard Males and Females". British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 31 (1): 128–135. doi:10.1111/j.2044-835x.2012.02084.x. PMID 23331111.

- Bem, Sandra (1981). "Gender Schema Theory: A Cognitive Account of Sex Typing". Psychological Review. 88 (4): 354–364. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.88.4.354. S2CID 144018764.

- Rodgers 2014.

- Clarricoates 1978.

- Clarricoates 1978, p. 357.

- Clarricoates 1978, p. 355.

- Clarricoates 1978, p. 360.

- Clarricoates 1978, p. 353.

- Rosenthal, Robert; Jacobsen, Lenore (1968). Pygmalion in the Classroom. London: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

- Pivnick, Patricia (1974). "Sex Role Socialisation: Observations in a First Grade Classroom (It's Hard to Change Your Image Once You're Typecast)". Thesis of Doctorate of Education at the University of Rochester: 159.

- Clarricoates 1978, p. 363.

- Guasp, April (2009). Homophobic Bullying in Britain's Schools: The Teachers' Report. London: Stonewall.

- Guasp, April (2009). Different Families: The Experiences of Children with Lesbian and Gay Parents. London: Stonewall.

- Rodgers 2014, p. 59.

- Rodgers 2014, p. 61.

- Rodgers 2014, p. 60.

- Psaki, S. Prospects (2016) 46: 109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-016-9379-0

- McCleary-Sills, Jennifer, et al. "Child Marriage: A Critical Barrier to Girls' Schooling and Gender Equality in Education." The Review of Faith & International Affairs, vol. 13, no. 3, 2015, pp. 69–80.

- Zuo, Jiping, and Shengming Tang. "Breadwinner Status and Gender Ideologies of Men and Women Regarding Family Roles." Sociological Perspectives, vol. 43, no. 1, 2000, pp. 29–43. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1389781.

- Esposito, Jennifer (2011). "Negotiating the gaze and learning the hidden curriculum: a critical race analysis of the embodiment of female students of color at a predominantly white institution". Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies.

- DeFrancisco, Victoria P. (2014). Gender in Communication. Los Angeles: Sage. pp. 168–173. ISBN 978-1-4522-2009-3.

- Kevin Seifert and Rosemary Sutton. (2009) Educational Psychology 2nd Edition. "Chapter 4: Student Diversity." pp. 73

- Wojtkiewicz, Roger A. (February 1992). "Diversity in Experiences of Parental Structure During Childhood and Adolescence". Demography. 29 (1): 59–68. doi:10.2307/2061363. ISSN 0070-3370. JSTOR 2061363. PMID 1547903.

- Khanal, Shaleen (15 March 2018). "Gender Discrimination in Education Expenditure in Nepal: Evidence from Living Standards Surveys". Asian Development Review. 35 (1): 155–174. doi:10.1162/adev_a_00109. ISSN 0116-1105.

- "Scholarships". Save - Leading The Policy Movement For Fairness and Due Process On Campus. 3 November 2020. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- "Do Women STEM College Programs Discriminate Against Males?". GovTech. 21 August 2019. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- Elsesser, Kim. "Women's Scholarships And Awards Eliminated To Be Fair To Men". Forbes. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- "Women-only scholarships under spotlight". Stuff. 31 January 2009. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- "Should female-only scholarships be abolished?". RNZ. 20 July 2008. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- Jacobs, J. A. (1996). "Gender Inequality and Higher Education". Annual Review of Sociology. 22: 153–85. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.22.1.153. S2CID 145628367.

- Solmon, Melinda A., Lee, Amelia M. (January 2000). "Research on Social Issues in Elementary School Physical Education". Elementary School Journal.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Cooper, Brenda (1 March 2002). "Boys Don't Cry and female masculinity: reclaiming a life & dismantling the politics of normative heterosexuality". Critical Studies in Media Communication. 19 (1): 44–63. doi:10.1080/07393180216552. ISSN 1529-5036. S2CID 145392513.

- Cassese, Erin C.; Bos, Angela L.; Schneider, Monica C. (1 July 2014). "Whose American Government? A Quantitative Analysis of Gender and Authorship in American Politics Texts". Journal of Political Science Education. 10 (3): 253–272. doi:10.1080/15512169.2014.921655. ISSN 1551-2169. S2CID 143498265.

- Taylor, Donna Lester (2004). ""Not just boring stories": Reconsidering the gender gap for boys". Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy. 48 (4): 290–298. doi:10.1598/JAAL.48.4.2.

- Booth D., Bruce F., Elliott-Johns S. (February 2009) Boys' Literacy Attainment: Research and related practice. Report for the 2009 Ontario Education Research Symposium. Centre for Literacy at Nipissing University. Retrieved from Ontario Ministry of Education website: http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/research/boys_literacy.pdf

- Martino W. (April 2008) Underachievement: Which Boys are we talking about? What Works? Research into Practice. The Literacy and Numeracy Secretariat. Retrieved from Ontario Ministry of Education website: http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/literacynumeracy/inspire/research/Martino.pdf

- Smith, Michael W.; Jeffrey D. Wilhelm (2002). "Reading don't fix no Chevys" : literacy in the lives of young men. Portsmouth, N.H.: Heinemann. ISBN 978-0867095098.

- Tapscott, D. (2009) Grown Up Digital. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- "Boy's Own Story", Reporter: Susan Ormiston, Producer: Marijka Hurko, 25 November 2003.

- Pahlke, Erin; Hyde, Janet Shibley; Allison, Carlie M. (1 July 2014). "The effects of single-sex compared with coeducational schooling on students' performance and attitudes: a meta-analysis". Psychological Bulletin. 140 (4): 1042–1072. doi:10.1037/a0035740. ISSN 1939-1455. PMID 24491022. S2CID 15121059.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 May 2011. Retrieved 31 January 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link), additional text. - "New Study Shows Homeschoolers Excel Academically". Home School Legal Defense Association. 10 August 2009. Archived from the original on 5 January 2013.

- Voyeur, Daniel (2014). "Gender Differences in Scholastic Achievement: A Meta-Analysis" (PDF). Psychological Bulletin. 140 (4): 1174–1204. doi:10.1037/a0036620. PMID 24773502.

- Stoet, Gijsbert; Geary, David C. (1 January 2015). "Sex differences in academic achievement are not related to political, economic, or social equality". Intelligence. 48: 137–151. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2014.11.006. S2CID 143234406.

- "The Significant Gender Gap in College Graduation Rates". Women In Academia Report. 9 November 2022. Retrieved 18 June 2023.

- "CO3.1: Educational attainment by gender" (PDF). OECD. Retrieved 18 June 2023.

- "College gender gap widens: 57% are women". USA Today. 19 October 2005. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- Bidwell, Allie (31 October 2014). "Women More Likely to Graduate College, but Still Earn Less Than Men". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- Christofides, Louis N.; Hoy, Michael; Yang, Ling (2009). "The Determinants of University Participation in Canada (1977–2003)". Canadian Journal of Higher Education. 39 (2): 1–24. doi:10.47678/cjhe.v39i2.483.

- Marklein, Mary Beth (19 October 2005). "College gender gap widens: 57% are women". USA Today. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- Droulet, D. (September 2007) Minding the Gender Gap. Retrieved from University Affairs website: "Minding the gender gap | University Affairs". Archived from the original on 28 May 2012. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- "Discrimination against women in education". THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF WORLD PROBLEMS & HUMAN POTENTIAL. 15 March 2023.

- "Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Discrimination as Sex Discrimination", Feminist Judgments, Cambridge University Press, pp. 266–333, 30 September 2020, doi:10.1017/9781108694643.007, ISBN 9781108694643, S2CID 243020689, retrieved 16 March 2023

- Busch, Elizabeth Kaufer; Thro, William E. (20 May 2018), "Title IX Implementing Regulations", Title IX, Routledge, pp. 125–128, doi:10.4324/9781315689760-8, ISBN 978-1-315-68976-0, retrieved 16 March 2023

- SteelFisher, Gillian K.; Findling, Mary G.; Bleich, Sara N.; Casey, Logan S.; Blendon, Robert J.; Benson, John M.; Sayde, Justin M.; Miller, Carolyn (29 October 2019). "Gender discrimination in the United States: Experiences of women". Health Services Research. 54 (S2): 1442–1453. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13217. ISSN 0017-9124. PMC 6864374. PMID 31663120.

- Wilson, Michelle (15 March 2023). Title IX, Education Amendments of 1972. doi:10.4135/9781412961165. ISBN 9781412961158.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - Musau, Zipporah (21 March 2018). "Africa grapples with huge disparities in education". Africa Renewal. 31 (3): 10–11. doi:10.18356/1a71d0ef-en. ISSN 2517-9829.

- "Millions of Young Girls Forced Into Marriage". Culture. 15 March 2013. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- Clarricoates, Katherine (1978). "'Dinosaurs in the Classroom'--A Re-examination of Some Aspects of the 'Hidden' Curriculum in Primary Schools". Women's Studies International Quarterly. 1 (4): 353–364. doi:10.1016/s0148-0685(78)91245-9.

- Rodgers, Jenny (2014). "Aspirational Practice: Gender Equality The challenge of gender and heterosexual stereotypes in primary Education". The STeP Journal. 1 (1): 58–68.