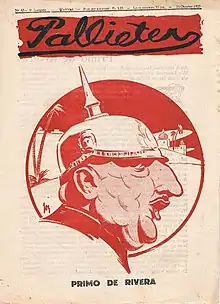

Miguel Primo de Rivera

Miguel Primo de Rivera y Orbaneja, 2nd Marquis of Estella, GE (8 January 1870 – 16 March 1930), was a Spanish dictator and military officer who ruled as prime minister of Spain from 1923 to 1930 during the last years of the Bourbon Restoration.

Miguel Primo de Rivera | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Primo de Rivera c. 1920 | |

| Prime Minister of Spain | |

| In office 15 September 1923 – 28 January 1930 | |

| Monarch | Alfonso XIII |

| Preceded by | Manuel García Prieto |

| Succeeded by | Dámaso Berenguer |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Miguel Primo de Rivera y Orbaneja 8 January 1870[1] Jerez, Spain |

| Died | 16 March 1930 (aged 60) Paris, France |

| Resting place | Church of La Merced, Jerez |

| Political party | Patriotic Union |

| Spouse |

Casilda Sáenz de Heredia

(m. 1902; died 1908) |

| Children | 6, including José Antonio, Miguel, and Pilar |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | Spanish Army |

| Years of service | 1884–1923 |

| Rank | Lieutenant general[n. 1] |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards | Laureate Cross of Saint Ferdinand |

He was born into a landowning family of Andalusian aristocrats. He met his baptism by fire in October 1893 in Cabrerizas Altas during the so-called Margallo War.[2] He moved up the military ladder, promoted to brigadier general (1911), division general (1914), and lieutenant general (1919).[3] He went on to serve as administrator of the Valencia, Madrid, and Barcelona military regions, distinguishing himself as a voice in favour of military withdrawal from Africa.

During the crisis of the Restoration regime, specifically upon political turmoil in the wake of setbacks in the Rif War, Primo de Rivera staged a military coup d'état on 13 September 1923 with help from a clique of Africanist generals close to King Alfonso XIII. The coup enjoyed the acquiescence of the monarch,[4] and Primo de Rivera was ensuingly tasked to form a government. He thereby proceeded to suspend the 1876 constitution and establish martial law.

His dictatorial rule was marked by authoritarian nationalism and populism.[5] Primo de Rivera initially said he would rule for only 90 days; however, he chose to remain in power, heading a military directorate. In December 1925, after the Alhucemas landing ended Rifian anti-colonial resistance, he installed a civil directory. From 1927 a policy of public spending on infrastructures was pursued and state monopolies such as oil company Campsa were created. Once economic tailwinds diminished, he lost the support of most of his generals, and he was forced to resign in January 1930 amid increasing inflation and civic unrest, dying abroad two months later.

Some of his children, such as José Antonio and Pilar, went on to become far-right leaders.

Early years

Miguel Primo de Rivera was born into a landowning military family of Jerez de la Frontera. His father was a retired colonel. His uncle, Fernando, was Captain General in Madrid and the soon-to-be first marquis of Estella. Fernando later participated in the plot to restore the constitutional monarchy in 1875, ending the tumultuous First Republic. His great-grandfather was Bértrand Primo de Rivera (1741–1813), a general and hero of the Spanish Resistance against Napoleon Bonaparte.

The young Miguel grew up as part of what Gerald Brenan called "a hard-drinking, whoring, horse-loving aristocracy" that ruled "over the most starved and down-trodden race of agricultural labourers in Europe." Studying history and engineering before deciding upon a military career, he won admission to the newly created General Military Academy in Toledo, and graduated in 1884.

Military career

His army career gave him a role as junior officer in the colonial wars in Morocco, Cuba and the Philippines. He then held several important military posts including the captain-generalship of Valencia, Madrid and Barcelona.

He showed courage and initiative in battles against the Berbers of the Rif region in northern Morocco, and promotions and decorations came steadily. Primo de Rivera became convinced that Spain probably could not hold on to its North African colony. For many years, the government had tried without success to crush the Berber rebels, wasting lives and money. He concluded Spain must withdraw from what was called Spanish Morocco if it could not dominate the colony. He was familiar with Cuba and the Philippines with the latter as an aide-de-camp during the Philippine Revolution against Emilio Aguinaldo and became a hostage along with Filipino exiles in Hong Kong after the Pact of Biak na Bato. in 1898 he watched the humiliating defeat in the Spanish–American War, bringing a close to his nation's once-great empire. That loss frustrated many Spaniards, Primo de Rivera included. They criticized the politicians and the parliamentary system which could not maintain order or foster economic development at home, nor preserve the vestiges of Spain's imperial glory.

.jpg.webp)

Primo de Rivera went to Madrid to serve in the Ministry of War with his uncle. Renowned for his amorous conquests, he reverted to the carefree days of his youth in Jerez. Then in 1902, he married a young Hispano-Cuban, Casilda Sáenz de Heredia. Their marriage was happy, and Casilda bore six children before her death in 1908, following the birth of Fernando. He later was sent on a military mission to France, Switzerland, and Italy in 1909.

The British historian Hugh Thomas says: "He would work enormously hard for weeks on end and then disappear for a juerga of dancing, drinking and love-making with gypsies. He would be observed almost alone in the streets of Madrid, swathed in an opera cloak, making his way from one café to another, and on returning home would issue a garrulous and sometimes even intoxicated communiqué -- which he would often have to cancel in the morning."[6]

Between 1909 and 1923, Primo de Rivera's career blossomed, but he became increasingly discouraged with the fortunes of his country. He was wounded in action in October 1911 in the Kert campaign while leading the infantry regiment San Fernando as Colonel.[7] Having returned to Spanish Morocco, he was promoted to brigadier general in 1911, the first graduate of the General Academy to receive such a promotion. Yet social revolution had flared briefly in Barcelona, during the Tragic Week of 1909. After the army had called up conscripts to fight in the Second Rif War in Morocco, Radical republicans and anarchists in Catalonia had proclaimed a general strike. Violence had erupted when the government declared martial law. Anticlerical rioters had burned churches and convents, and tensions grew as socialists and anarchists pressed for radical changes in Spain. The government proved unable to reform itself or the nation and frustration mounted.

After 1918, post-World War I economic difficulties heightened social unrest in Spain. The Cortes (Spanish parliament) under the constitutional monarchy seemed to have no solution to Spain's unemployment, labor strikes, and poverty. In 1921, the Spanish army suffered a stunning defeat in Morocco at the Battle of Annual, which discredited the military's North African policies. By 1923, deputies of the Cortes called for an investigation into the responsibility of King Alfonso XIII and the armed forces for the debacle. Rumors of corruption in the army became rampant.

Establishment of dictatorship

On 13 September 1923, the indignant military, headed by Captain General Miguel Primo de Rivera in Barcelona, overthrew the parliamentary government, upon which Primo de Rivera established himself as dictator. In his typically florid prose, he issued a Manifesto explaining the coup to the people. Resentful of the parliamentarians' attacks against him, King Alfonso tried to give Primo de Rivera legitimacy by naming him prime minister. In justifying his coup d'état, Primo de Rivera announced: "Our aim is to open a brief parenthesis in the constitutional life of Spain and to re-establish it as soon as the country offers us men uncontaminated with the vices of political organization."[8] In other words, he believed that the old class of politicians had ruined Spain, that they sought only their own interests rather than patriotism and nationalism.

Although many leftists opposed the dictatorship, some of the public supported Primo de Rivera. Those Spaniards were tired of the turmoil and economic problems and hoped a strong leader, backed by the military, could put their country on the right track. Others were enraged that the parliament had been brushed aside. As he travelled through Spain, his emotional speeches left no doubt that he was a Spanish patriot. He proposed to keep the dictatorship in place long enough to sweep away the mess created by the politicians. In the meantime, he would use the state to modernize the economy and alleviate the problems of the working class.

Primo de Rivera began by appointing a supreme directorate of eight military men, with himself as president. He then decreed martial law and fired civilian politicians in the provinces, replacing them with middle-ranking officers. When members of the Cortes complained to the king, Alfonso dismissed them, and Primo de Rivera suspended the constitution and dissolved the legislative body. He also moved to repress separatists, who wanted to make the Basque provinces and Catalonia independent from Spain. Despite some reservations, the great Spanish philosopher and intellectual, José Ortega y Gasset, wrote:

"The alpha and omega of the task that the military Directory has imposed is to make an end of the old politics. The purpose is so excellent, that there is no room for objections. The old politics must be ended."

Nevertheless, other intellectuals such as Miguel de Unamuno and Vicente Blasco Ibáñez criticized the regime and were exiled.

The dictator enjoyed several successes in the early years of his regime. Chief among them was Morocco, which had been festering since the start of the 20th century. Primo de Rivera talked of abandoning the colony altogether, unless sufficient resources were available to defeat the rebellion, and began withdrawing Spanish forces. But when the Moroccans attacked the French sector, they drove the French and Spanish to unite to crush the defiance in 1925. He went to Africa to help lead the troops in person, and 1927 brought victory to the Franco-Spanish forces. Grateful Spaniards rejoiced to think that decades of North African bloodletting and recriminations were over.

Promoting infrastructure

Primo de Rivera also worked to build infrastructure for his economically backward country. Spain had few cars when he came to power; by 1930, and Rivera aimed to expand this. The Barcelona Metro, started many years earlier, opened in 1924. His economic planners built dams to harness the hydroelectric power of rivers, especially the Duero and the Ebro, and to provide water for irrigation. For the first time, electricity reached some of Spain's rural regions. The regime upgraded Spain's railroads, and this helped the Spanish iron and steel industry prosper. Between 1923 and 1927, foreign trade increased 300%. Overall, his government intervened to protect national producers from foreign competition. Such economic nationalism was largely the brainchild of Primo de Rivera's finance minister, José Calvo Sotelo. Spain benefited from the European post-World War I boom, but the gains were concentrated with the wealthy.[9]

The tranquility was, in part, due to the dictatorship's ways of accommodating the interests of Spanish workers. Imitating the example of Benito Mussolini in Italy, Primo de Rivera forced management and labor to cooperate by organizing 27 corporations (committees) representing different industries and professions. Within each corporation, government arbitrators mediated disputes over wages, hours, and working conditions. This gave Spanish labor more influence than ever before and this might be the reason why the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) and Workers' General Union (UGT) were quick to cooperate with the government and its leaders affiliated themselves with the committees mentioned before.[10] Individual workers also benefited because the regime undertook massive public works. The government financed such projects with huge public loans, which Calvo Sotelo argued would be repaid by the increased taxes resulting from economic expansion. Unemployment largely disappeared.

But Primo de Rivera brought order to Spain with a price: his regime was a dictatorship. He censored the press. When intellectuals criticized the government, he closed El Ateneo, the country's most famous political and literary club. The largely anarchist National Confederation of Labour (CNT) was decreed illegal and, without the support of the PSOE, the general strikes organised by the organisation were dismantled violently by the army. To suppress the separatist fever in Barcelona, the regime tried to expunge Catalan culture. It was illegal to use Catalan in church services or to dance the sardana. Furthermore, many of the dictator's economic reforms did not actually help the poor as huge public spending led to inflation, which the rich could cope with more easily. This led to a huge income disparity between the wealthy and working classes in Spain at the time.

Despite his paternalistic conservatism, Primo de Rivera was enough of a reformer and his policies were radical enough to threaten the interests of the traditional power elite. According to British historian Gerald Brenan, "Spain needed radical reforms and he could only govern by the permission of the two most reactionary forces in the country—the Army and the Church."

Primo de Rivera dared not tackle what was seen as Spain's most pressing problem, agrarian reform, because it would have provoked the great landholding elite. Writes historian Richard Herr, "Primo was not one to waken sleeping dogs, especially if they were big."

Primo de Rivera chiefly failed because he did not create a viable, legitimate political system to preserve and continue his reforms. He seems to have sincerely wanted the dictatorship to be as brief as possible and initially hoped that Spain could live with the Constitution of 1876 and a new group of politicians. The problem was to find new civilian leadership to take the place of the military.

In 1923, he began to create a new "apolitical" party, the Patriotic Union (UP), which was formally organized the following year. Primo de Rivera liked to claim that members of the UP were above the squabbling and corruption of petty politics, that they placed the nation's interests above their own. He thought it would bring ideal democracy to Spain by representing true public opinion. But the UP quite obviously was a political party, despite the dictator's naive protestations. Furthermore, it failed to attract enthusiastic support or even many members.

On 3 December 1925 he moved to restore legitimate government by dismissing the military Directory and replacing it with civilians. Still, the Constitution remained suspended, and criticisms of the regime grew. By summer 1926, former politicians, led by conservative José Sánchez-Guerra y Martínez, pressed the king to remove Primo de Rivera and restore constitutional government. To demonstrate his public support, Primo de Rivera ordered the UP to conduct a plebiscite in September. Voters could endorse the regime or abstain. About a third of those able to vote declined to go to the polls; despite this, The New York Times called the result "a record vote", noting that the turnout was four times higher than any Spanish election until then.[11] Other media were more critical: The Advocate called the vote "a farce".[12]

National Assembly

Nevertheless, buoyed by his victory, Primo de Rivera decided to promote a body tasked with the elaboration of a constitutional draft. On 10 October 1927, with the king in attendance, he opened a National Assembly. Although they met in the Cortes chamber, members of the regime-appointed assembly could only advise Primo de Rivera. They had no legislative power. In 1929, following guidance from the dictator, the assembly finally produced a new constitution draft. Among its provisions, it gave women the vote because Primo de Rivera believed their political views less susceptible to political radicalism. He intended to have the nation accept the new constitution in another plebiscite, to be held in 1930.

_-_Fondo_Mar%C3%ADn-Kutxa_Fototeka.jpg.webp)

Fall from power and death

As the economic boom ended, Spaniards gradually became tired of the dictatorship. The value of the peseta fell against foreign currencies, 1929 brought a bad harvest, and Spain's imports far outstripped the worth of its exports. Conservative critics blamed rising inflation on the government's spending for public works projects. Although no one recognized it at the time, the final months of the year brought the international economic slump which turned into the Great Depression of the 1930s.

When Primo de Rivera lost the support of the king and the armed forces, his dictatorship was doomed. The Spanish military had never unanimously backed his seizure of power, although it had tolerated his rule. But when Primo de Rivera began to inject politics into promotions for the artillery corps, it provoked hostility and opposition. Troubled by the regime's failure to legitimize itself or to solve the country's woes, the king also began to draw away. Alfonso, who had sponsored the establishment of Madrid's University City, watched with dismay as the country's students took to the streets to protest the dictatorship and the king's support for it. A clandestine pamphlet portrayed Alfonso as Primo de Rivera's dancing partner. Yet the king did not have determination to remove Primo de Rivera. On 26 January 1930, the dictator asked the military leaders if he still had their support. Their lukewarm responses, and his recognition that the king no longer backed him, persuaded him to resign two days later. Primo de Rivera retired and moved to Paris, where he died a month and a half later at the age of 60 from a combination of fever and diabetes on 16 March 1930.

Aftermath

In the early 1930s, as with most of the Western world during and after the Great Depression, Spain fell into economic and political chaos. Alfonso XIII appointed General Dámaso Berenguer, one of Primo de Rivera's opponents, to govern. This government promptly failed in its attempt to return to ordinary constitutional order. Different presidential candidates attempted to restore the legitimacy of the monarch, who had discredited himself by siding with the dictatorship. Eventually, municipal elections were called for on 12 April 1931. While monarchist parties won in the overall polls, republican candidates commanded the majority in urban centres, winning the elections in 41 provincial capitals including Madrid and Barcelona. In April 1931, General José Sanjurjo informed the King that he could not count on the loyalty of the armed forces. Alfonso XIII went into exile on 14 April 1931, not formally abdicating until he did so in 1941 in favour of his son, Juan de Borbón.[13] The act ushered in the Second Republic. Two years later Primo de Rivera's eldest son, José Antonio, founded the Falange, a Spanish fascist party. Both José Antonio and his brother Fernando were arrested in March 1936 by the republic, and were executed in Alicante prison by Republican forces once the Spanish Civil War began in July 1936. The Nationalists led by Francisco Franco won the Civil War and established a far more authoritarian regime. By that time, many Spaniards regarded Primo de Rivera's relatively mild regime and its economic optimism with greater fondness.[14]

See also

Notes

- Posthumously promoted to the honorific rank of Captain General by the Francoist dictatorship

References

- Charles Petrie; Charles Alexander Petrie, Sir bart. (1963). King Alfonso XIII and His Age. Chapman & Hall. p. 179.

- Quiroga, Alejandro (2022). Miguel Primo de Rivera: Dictadura, populismo y nación. Editorial Crítica. ISBN 978-8491994671.

- Casals, Xavier (2004). "Miguel Primo de Rivera, el espejo de Franco". Miguel Primo de Rivera y Orbaneja. Madrid: Ediciones B. pp. 152, 154, 162. ISBN 84-666-1447-8.

- Television documentary from CC&C Ideacom Production,"Apocalypse Never-Ending War 1918–1926", part 2, aired on DR K on 22 October 2018

- Canal, Jordi (27 January 2023). "Primo de Rivera, 'el inventor del populismo de derechas'". El País.

- Hugh Thomas, The Spanish Civil War, p. 17

- "1911 Dura acción de castigo en el Rif". Diario de Cádiz. 10 October 2011.

- Richard A. H. Robinson, The Origins of Franco’s Spain – The Right, the Republic and Revolution, 1931–1936 (University of Pittsburgh Press, 1970) p. 28.

- Commire, Anne (1994). Historic World Leaders: Europe (L-Z). Gale Research Incorporated. p. 1157.

- Murray Bookchin (1998) The Spanish Anarchists: The Heroic Years, 1868–1936. Publisher: AK Press

- TIMES, Special Cable to THE NEW YORK TIMES (1926-09-14). "SPANISH PLEBISCITE DRAWS RECORD VOTE; De Rivera at End Estimates Total Is Four Times That of Any General Election. ABSTENTIONISTS ARRESTED Barcelona Police Hold Those Who Agitated Against Signing Endorsement of Government". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-01-20.

- "SPANISH FARCE. Three Days' Plebiscite". The Advocate. 1926-09-18. Retrieved 2022-01-20.

- Suarez, Eduardo (2006). "Tres días de abril que revolucionaron España". La Aventura de la Historia. 90: 54–60.

- Raymond Carr, Spain, 1808–1975 (2nd ed 1982) pp 564–591

Further reading

- Ben-Ami, Shlomo. Fascism from Above: The Dictatorship of Primo de Rivera, 1923–1930, Oxford 1983.

- Carr, Raymond. Spain, 1808–1975, 2nd ed. 1982, pp. 564–591.

- Montes, Pablo. "La Dictadura de Primo de Rivera y la Historiografía: Una Confrontación Metodológica," Historia Social (2012), Issue 74, pp 167–184.

- Quiroga, Alejandro. Making Spaniards: Primo de Rivera and the Nationalization of the Masses, 1923–30, 2007. Excerpt and text search.

- Rial, James H. Revolution from Above: The Primo De Rivera Dictatorship in Spain, 1923–1930, 1986.

- Smith, Angel. "The Catalan Counter-revolutionary Coalition and the Primo de Rivera Coup, 1917–23," European History Quarterly (2007) 37#1 pp 7–34. Online version.