Lost Generation

The Lost Generation was the social generational cohort in the Western world that was in early adulthood during World War I. The generation is generally defined as people born from 1883 to 1900, and came of age in either the 1900s, or the 1910s. The term is also particularly used to refer to a group of American expatriate writers living in Paris during the 1920s.[1][2][3] Gertrude Stein is credited with coining the term, and it was subsequently popularised by Ernest Hemingway, who used it in the epigraph for his 1926 novel The Sun Also Rises: "You are all a lost generation."[4][5] "Lost" in this context refers to the "disoriented, wandering, directionless" spirit of many of the war's survivors in the early postwar period.[6]

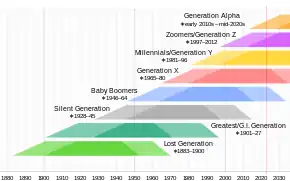

| Part of a series on |

| Social generations of the Western world |

|---|

|

In the wake of the Industrial Revolution, Western members of the Lost Generation grew up in societies that were more literate, consumerist, and media-saturated than ever before, but which also tended to maintain strictly conservative social values. Young men of the cohort were mobilized on a mass scale for the First World War, a conflict that was often seen as the defining moment of their age group's lifespan. Young women also contributed to and were affected by the War, and in its aftermath gained greater freedoms politically and in other areas of life. The Lost Generation was also heavily vulnerable to the Spanish flu pandemic and became the driving force behind many cultural changes, particularly in major cities during what became known as the Roaring Twenties.

Later in their midlife, they experienced the economic effects of the Great Depression and often saw their own sons leave for the battlefields of the Second World War. In the developed world, they tended to reach retirement and average life expectancy during the decades after the conflict, but some significantly outlived the norm. The last surviving person who was known to have been born during the 19th century was Nabi Tajima, who died in 2018. Most members were parents of the Greatest Generation and Silent Generation.

Terminology

The first named generation, the term "Lost Generation" is used for the young people who came of age around the time of World War I. In Europe, they are mostly known as the "Generation of 1914", for the year World War I began. In France they were sometimes called the Génération du feu, the "(gun)fire generation". In the United Kingdom, the term was originally used for those who died in the war,[7] and often implicitly referred to upper-class casualties who were perceived to have died disproportionately, robbing the country of a future elite.[8] Many felt that "the flower of youth and the best manhood of the peoples [had] been mowed down,"[9], for example, such notable casualties as the poets Isaac Rosenberg, Rupert Brooke, Edward Thomas and Wilfred Owen,[10] composer George Butterworth and physicist Henry Moseley.

Date and age range definitions

Authors William Strauss and Neil Howe define the Lost Generation as the cohort born from 1883 to 1900, who came of age during World War I and the Roaring Twenties.[11]

Characteristics

Family life and upbringing

When the Lost Generation was growing up, the ideal family arrangement was generally seen as the man of the house being the breadwinner and primary authority figure whilst his wife dedicated herself to caring for the home and children. Most, even less well-off, married couples attempted to conform to this ideal.[12][13] It was common for family members of three different generations to share a home.[14] Wealthier households also tended to include domestic servants, though their numbers would have varied from a single maid to a large team depending on how rich the family was.[15]

Public concern for the welfare of children was intensifying by the later 19th century with laws being passed and societies formed to prevent their abuse. The state increasingly gained the legal right to intervene in private homes and family life to protect minors from harm.[16][17][18] However, beating children for misbehaviour was not only common but viewed as the duty of a responsible caregiver.[19]

Health and living conditions

Sewer systems designed to remove human waste from urban areas had become widespread in industrial cities by the late 19th century helping to reduce the spread of diseases such as cholera.[21][22] Legal standards for the quality of drinking water also began to be introduced.[23] However, the introduction of electricity was slower and during the formative years of the Lost Generation gas lights and candles were still the most common form of lighting.[24]

Though statistics on child mortality dating back to the beginning of the Lost Generation's lifespan are limited, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention reports that in 1900 one in ten American infants died before their first birthday.[25] Figures for the United Kingdom state that during the final years of the 19th century, mortality in the first five years of childhood was plateauing at a little under one in every four births. At around one in three in 1800, the early childhood mortality rate had declined overall throughout the next hundred years but would fall most sharply during the first half of the 20th century, reaching less than one in twenty by 1950. This meant that members of the Lost Generation were somewhat less likely to die at a very early age than their parents and grandparents, but were significantly more likely to do so than children born even a few decades later.[26]

Literacy and education

Laws restricting child labour in factories had begun to appear from around 1840 onwards[27][28][29] and by the end of the 19th century, compulsory education had been introduced throughout much of the Western world for at least a few years of childhood.[30][31] By 1900, levels of illiteracy had fallen to less than 11% in the United States, around 3% in Great Britain, and only 1% in Germany.[32][33][34] However, the problems of illiteracy and lack of school provision or attendance were felt more acutely in parts of Eastern and Southern Europe.[35][34][36]

Schools of this time period tended to emphasise strict discipline, expecting pupils to memorize information by rote. To help deal with teacher shortages, older students were often used to help supervise and educate their younger peers. Dividing children into classes based on age became more common as schools grew.[37]

However, whilst elementary schooling was becoming increasingly accessible for Western children at the turn of the century, secondary education was still much more of a luxury. Only 11% of American fourteen to seventeen-year-olds were enrolled at High School in 1900, a figure which had only marginally increased by 1910.[38] Though the school leaving age was officially meant to be 14 by 1900, until the First World War, most British children could leave school through rules put in place by local authorities at 12 or 13 years old.[39] It was not uncommon at the end of the 19th century for Canadian children to leave school at nine or ten years old.[40]

Leisure and play

By the 1890s, children's toys entered into mass production.[41] In 1893, the British toy company William Britain revolutionized the production of toy soldiers by devising the method of hollow casting, making soldiers that were cheaper and lighter than their competitors.[42] This led to metal toy soldiers, which had previously been the preserve of boys from wealthier families, gaining mass appeal during the late Victorian and Edwardian period.[43] Dolls often sold by street vendors at a low price were popular with girls. Teddy bears appeared for the first time in the early 1900s.[44] Tin plated penny toys were also sold by street sellers for a single penny.[45]

The turn of the 20th century saw a surge in public park building in parts of the west to provide public space in rapidly growing industrial towns.[46] They provided a means for children from different backgrounds to play and interact together,[47] sometimes in specially designed facilities.[48] They held frequent concerts and performances.[49]

Popular culture and mass media

%252C_1912.jpg.webp)

Beginning around the middle of the 19th century, magazines of various types which had previously mainly targeted the few that could afford them found rising popularity among the general public.[50] The latter part of the century not only saw rising popularity for magazines targeted specifically at young boys but the development of a relatively new genre aimed at girls.[51]

A significant milestone was reached in the development of cinema when, in 1895, projected moving images were first shown to a paying audience in Paris. Early films were very short (generally taking the form of newsreels, comedic sketches, and short documentaries). They lacked sound but were accompanied by music, lectures, and a lot of audience participation. A notable film industry had developed by the start of the First World War.[52]

Military service in the First World War

The Lost Generation is best known as being the cohort that primarily fought in World War I.[53] More than 70 million people were mobilized during the First World War, around 8.5 million of whom were killed and 21 million wounded in the conflict. About 2 million soldiers are believed to have been killed by disease, while individual battles sometimes caused hundreds of thousands of deaths.[54]

Around 60 million of the enlisted originated from the European continent,[54] which saw its younger men mobilized on a mass scale. Most of Europe's great powers operated peacetime conscription systems where men were expected to do a brief period of military training in their youth before spending the rest of their lives in the army reserve. Nations with this system saw a huge portion of their manpower directly invested in the conflict: 55% of male Italians and Bulgarians aged 18 to 50 were called to military service. Elsewhere the proportions were even higher: 63% of military-aged men in Serbia, 78% in Austro-Hungary, and 81% of military-aged men in France and Germany served. Britain, which traditionally relied primarily on the Royal Navy for its security, was a notable exception to this rule and did not introduce conscription until 1916.[55] Around 5 million British men fought in the First World War out of a total United Kingdom population of 46 million including women, children, and men too old to bear arms.[54][56]

Additionally, nations recruited heavily from their colonial empires. Three million men from around the British Empire outside the United Kingdom served in the British Army as soldiers and laborers,[57] whilst France recruited 475,000 soldiers from its colonies.[58] Other nations involved include the United States which enlisted 4 million men during the conflict and the Ottoman Empire which mobilized 2,850,000 soldiers.[59]

Beyond the extent of the deaths, the war had a profound effect on many of its survivors, giving many young men severe mental health problems and crippling physical disabilities.[60][61] The war also unsettled many soldiers' sense of reality, who had gone into the conflict with a belief that battle and hardship was a path to redemption and greatness. When years of pain, suffering and loss seemed to bring about little in the way of a better future, many were left with a profound sense of disillusionment.[62][63]

Young women in the 1910s and '20s

Though soldiers on the frontlines of the First World War were almost exclusively men, women contributed to the war effort in other ways. Many took the jobs men had left in previously male-dominated sectors such as heavy industry, while some even took on non-combat military roles. Many, particularly wealthier women, took part in voluntary work to contribute to the war effort or to help those suffering due to it, such as the wounded or refugees. Often they were experiencing manual labor for the first time. However, this reshaping of the female role led to fears that the sexes having the same responsibilities would disrupt the fabric of society and that more competition for work would leave men unemployed and erode their pay. Most women had to exit the employment they had taken during the war as soon as it concluded.[64][65][66]

The war also had a personal impact on the lives of female members of the Lost Generation. Many women lost their husbands in the conflict, which frequently meant losing the main breadwinner of the household. However, war widows often received a pension and financial assistance to support their children. Even with some economic support, raising a family alone was often financially difficult and emotionally draining, and women faced losing their pensions if they remarried or were accused of engaging in frowned-upon behavior. In some cases, grief and the other pressures on them drove widows to alcoholism, depression, or suicide.[67][68][69] Additionally, the large number of men killed in the First World War made it harder for many young women who were still single at the start of conflict to get married; this accelerated a trend towards them gaining greater independence and embarking on careers.[70]

Women's gaining of political rights sped up in the Western world after the First World War, while employment opportunities for unmarried women widened. This time period saw the development of a new type of young woman in popular culture known as a flapper, who was known for their rebellion against previous social norms. They had a physically distinctive appearance compared to their predecessors only a few years earlier, cutting their hair into bobs, wearing shorter dresses and more makeup, while taking on a new code of behaviour filled with more recklessness, party-going and overt sexuality.[71][72][73]

Aftermath of the First World War

The aftermath of the First World War saw substantive changes in the political situation, including a trend towards republicanism, the founding of many new relatively small nation-states which had previously been part of larger empires, and greater suffrage for groups such as the working class and women. France and the United Kingdom both gained territory from their enemies, while the war and the damage it did to the European empires are generally considered major stepping stones in the United States' path to becoming the world's dominant superpower. The German and Italian populations' resentment against what they generally saw as a peace settlement that took too much away from the former or didn't give enough to the latter fed into the fascist movements, which would eventually turn those countries into totalitarian dictatorships. For Russia, the years after its revolution in 1917 were plagued by disease, famine, terror, and civil war eventually concluded in the establishment of the Soviet Union.[74][75][76]

.png.webp)

The immediate post-World War One period was characterized by continued political violence and economic instability.[74] The late 1910s saw the Spanish flu pandemic, which was unusual in the sense that it killed many younger adults of the same Lost Generation age group that had mainly died in the war.[77] Later, especially in major cities, much of the 1920s is considered to have been a more prosperous period when the Lost Generation, in particular, escaped the suffering and turmoil they had lived through by rebelling against the social and cultural norms of their elders.[78][79][80][81][82][83][84]

Politics and economics

This more optimistic period was short-lived, however, as 1929 saw the beginning of the Great Depression, which would continue throughout the 1930s and become the longest and most severe financial downturn ever experienced in Western industrialized history. Though it had begun in the United States, the crises led to sharp increases in worldwide unemployment, reductions in economic output and deflation. The depression was also a major catalyst for the rise of Nazism in Germany and the beginnings of its quest to establish dominance over the European continent, which would eventually lead to World War II in Europe. Additionally, the 1930s saw the less badly damaged Imperial Japan engage in its own empire-building, contributing to conflict in the Far East, where some scholars have argued the Second World War began as early as 1931.[85][86]

Popular media

The 1930s saw rising popularity for radio, with the vast majority of Western households having access to the medium by the end of the decade. Programming included soap operas, music, and sport. Educational broadcasts were frequently available. The airwaves also provided a source of news and, particularly for the era's autocratic regimes, an outlet for political propaganda.[87][88][89][90]

Second World War

When World War II broke out in 1939, the Lost Generation faced a major global conflict for the second time in their lifetime, and now often had to watch their sons go to the battlefield.[92][93] The place of the older generation who had been young adults during World War I in the new conflict was a theme in popular media of the time period, with examples including Waterloo Bridge and Old Bill and Son. Civil defense organizations designed to provide a final line of resistance against invasion and assist in home defense more broadly recruited heavily from the older male population.[94][91][95][90] Like in the First World War, women helped to make up for labour shortages caused by mass military recruitment by entering more traditionally masculine employment and entering the conflict more directly in female military branches and underground resistance movements. However, those in middle age were generally less likely to become involved in this kind of work than the young. This was particularly true of any kind of military involvement.[96][97][98][99]

In later life

In the West, the Lost Generation tended to reach the end of their working lives around the 1950s and 1960s.[100][101] For those members of the cohort who had fought in World War I, their military service frequently was viewed as a defining moment in their lives even many years later. Retirement notices of this era often included information on a man's service in the First World War.[93]

Though there were slight differences between individual countries and from one year to the next, the average life expectancy in the developed world during the 1950s, 1960s and early 1970s was typically around seventy years old.[102][103][104][105][106] However, some members of the Lost Generation outlived the norm by several decades. Nabi Tajima, the last surviving person known to have been born in the 19th century, died in 2018.[107] The final remaining veteran to have served in World War I in any capacity was Florence Green, who died in 2012, while Claude Choules, the last veteran to have been involved in combat, had died the previous year. However, these individuals were born in 1902 and 1901 respectively, putting them outside the usual birth years for the Lost Generation.[108][109][110]

In literature

In his memoir A Moveable Feast (1964), published after Hemingway's and Stein's deaths, Ernest Hemingway writes that Gertrude Stein heard the phrase from a French garage owner who serviced Stein's car. When a young mechanic failed to repair the car quickly enough, the garage owner shouted at the young man, "You are all a 'génération perdue'."[111]: 29 While telling Hemingway the story, Stein added: "That is what you are. That's what you all are ... all of you young people who served in the war. You are a lost generation."[111]: 29 Hemingway thus credits the phrase to Stein, who was then his mentor and patron.[112]

The 1926 publication of Hemingway's The Sun Also Rises popularized the term; that novel serves to epitomize the post-war expatriate generation.[113]: 302 However, Hemingway later wrote to his editor Max Perkins that the "point of the book" was not so much about a generation being lost, but that "the earth abideth forever".[114]: 82 Hemingway believed the characters in The Sun Also Rises may have been "battered" but were not lost.[114]: 82

Consistent with this ambivalence, Hemingway employs "Lost Generation" as one of two contrasting epigraphs for his novel. In A Moveable Feast, Hemingway writes, "I tried to balance Miss Stein's quotation from the garage owner with one from Ecclesiastes." A few lines later, recalling the risks and losses of the war, he adds: "I thought of Miss Stein and Sherwood Anderson and egotism and mental laziness versus discipline and I thought 'who is calling who a lost generation?'"[111]: 29–30

Very different due to the historical and cultural climate of his country was Boris Pasternak, whose novel Doctor Zhivago well relates the political realities and personal effects (typically great tragedy) of the Russian Revolution, Russian Civil War, and the effects of Stalinist rule.

Themes

The writings of the Lost Generation literary figures often pertained to the writers' experiences in World War I and the years following it. It is said that the work of these writers was autobiographical based on their use of mythologized versions of their lives.[115] One of the themes that commonly appear in the authors' works is decadence and the frivolous lifestyle of the wealthy.[116] Both Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald touched on this theme throughout the novels The Sun Also Rises and The Great Gatsby. Another theme commonly found in the works of these authors was the death of the American dream, which is exhibited throughout many of their novels.[117] It is particularly prominent in The Great Gatsby, in which the character Nick Carraway comes to realize the corruption that surrounds him.

Notable figures

Notable figures of the Lost Generation include F. Scott Fitzgerald,[118] Gertrude Stein, Ernest Hemingway, T. S. Eliot,[119] Ezra Pound, Jean Rhys[120] Henry Strater,[121] and Sylvia Beach.[122]

See also

References

- Madsen, Alex (2015). Sonia Delaunay: Artist of the Lost Generation. Open Road Distribution. ISBN 978-1-5040-0851-8.

- Fitch, Noel Riley (1983). Sylvia Beach and the Lost Generation: A History of Literary Paris in the Twenties and Thirties. WW Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-30231-8.

- Monk, Craig (2010). Writing the Lost Generation: Expatriate Autobiography and American Modernism. University of Iowa Press. ISBN 978-1-58729-743-4.

- Hemingway, Ernest (1996). The Sun Also Rises. New York: Scribner. ISBN 978-0-684-83051-3. OCLC 34476446.

- Monk, Craig (2010). Writing the Lost Generation: Expatriate Autobiography and American Modernism. Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-58729-743-4. Archived from the original on 4 August 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- Hynes, Samuel (1990). A War Imagined: The First World War and English Culture. London: The Bodley Head. p. 386. ISBN 978-0-370-30451-9.

- "The Lost Generation: the myth and the reality". Aftermath – when the boys came home. Archived from the original on 1 December 2009. Retrieved 6 November 2009.

- Winter, J. M. (November 1977). "Britain's 'Lost Generation of the First World War" (PDF). Population Studies. 31 (3): 449–466. doi:10.2307/2173368. JSTOR 2173368. PMID 11630506. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 July 2015. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- The Nation. J.H. Richards. 1919.

- "What was the 'lost generation'?". Schools Online World War One. BBC. Archived from the original on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- Strauss, William; Howe, Neil (1991). Generations: The History of Americas Future. 1584 to 2069. New York: William Morrow and Company. pp. 247–260. ISBN 978-0-688-11912-6.

- "Family Life: New Roles for Wives and Children". www.encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- "Everywoman in 1910: No vote, poor pay, little help - Why the world had to change". mirror.co.uk. 8 March 2010. Archived from the original on 1 March 2013. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- "Three-Generation Households: Are They History?". Silver Century Foundation. 27 March 2017. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- Wallis, Lucy (21 September 2012). "Servants: A life below stairs". BBC News. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- Myers, John E. B. "A Short History of Child Protection in America" (PDF). Sage Publishing. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 March 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - "A history of child protection". OpenLearn. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- Swain, Shurlee (October 2014). "History of child protection legislation" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- Geoghegan, Tom (5 March 2008). "Was childhood ever innocent?". Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- Elmasry, Faiza (22 April 2020). "Historian Explores the Evolution of Personal Hygiene". www.voanews.com. Archived from the original on 24 July 2021. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- "How London got its Victorian sewers". OpenLearn. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- "History of Sewers". Greywater Action. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- "Slow Sand Filtration of Water" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 October 2012. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- "The Electric Light System". Thomas Edison National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service). Archived from the original on 28 June 2021. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- "Achievements in Public Health, 1900-1999: Healthier Mothers and Babies". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 23 July 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- "United Kingdom: child mortality rate 1800-2020". Statista. Archived from the original on 27 March 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- O'Sullivan, Michael E. (1 January 2006). "Review of Kastner, Dieter, Kinderarbeit im Rheinland: Entstehung und Wirkung des ersten preußischen Gesetzes gegen die Arbeit von Kindern in Fabriken von 1839". www.h-net.org. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- Hindman, Hugh (18 December 2014). The World of Child Labor: An Historical and Regional Survey. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-45386-4.

- "Timeline". Child labor in the U.S. Archived from the original on 21 November 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- "Mass Primary Education in the Nineteenth Century". www.sociostudies.org. Archived from the original on 20 May 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- Grinin, Leonid E.; Ilyin, Ilya V.; Herrmann, Peter; Korotayev, Andrey V. (2016). Globalistics and globalization studies: Global Transformations and Global Future. ООО "Издательство "Учитель". p. 66. ISBN 978-5-7057-5026-9. Archived from the original on 20 May 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- "National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL)". nces.ed.gov. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- Lloyd, Amy. "Education, Literacy and the Reading Public" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 May 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

...by 1900 illiteracy for both sexes [in England and Wales] had dropped to around 3 percent... by the late nineteenth century, the gap [in illiteracy] between England, Wales and Scotland had narrowed and closed

- "Parallel worlds: literacy as a yardstick for development". Archived from the original on 20 May 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- Mironov, Boris N. (1991). "The Development of Literacy in Russia and the USSR from the Tenth to the Twentieth Centuries". History of Education Quarterly. 31 (2): 229–252. doi:10.2307/368437. ISSN 0018-2680. JSTOR 368437. S2CID 144460404.

- "Moving towards mass literacy in Spain, 1860-1930" (PDF). May 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 May 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- "Education – Western education in the 19th century". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- "The 1900s Education: Overview | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on 24 May 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- "The school leaving age: what can we learn from history?". HistoryExtra. 12 April 2008. Archived from the original on 8 June 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- Oreopoulos, Philip (May 2005). "Canadian Compulsory School Laws and their Impact on Educational Attainment and Future Earnings" (PDF). Statistics Canada. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- "Toy Timeline". Brighton museums. Archived from the original on 20 May 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- Hampshire Museums Service (Archived 14 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine). Retrieved on 25 August 2008.

- Bedford, Gavin. "Toy Soldiers ... Just child's play?". Egham Museum. Archived from the original on 20 May 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- "Popular Toys in History: What Your Ancestors Played With". Ancestry Blog. 10 December 2014. Archived from the original on 20 May 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- "An Edwardian Christmas". Museum of London. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- "America's Most Visited City Parks" (PDF). Retrieved 13 December 2009.

- "Research reveals rowdy past of UK's parks". manchester. Archived from the original on 14 August 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- "Urban Parks of the Past and Future". www.pps.org. Archived from the original on 20 May 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- "Parks and Recreation: the Victorian way". www.marshalls.co.uk. 24 February 2016. Archived from the original on 20 May 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- "History of publishing – The 19th century and the start of mass circulation". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 13 June 2015. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- Brotner, Kirsten (1988). English Children and Their Magazines, 1751–1945. ISBN 978-0-300-04010-4. JSTOR j.ctt2250w7m. Archived from the original on 20 May 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - "A very short history of cinema". National Science and Media Museum. Archived from the original on 20 May 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- Simpson, Trevor (17 January 2014). "WW1: Can we really know the Lost Generation?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- Herbert, Tom (11 November 2018). "World War 1 in numbers: The mind-blowing scale of WW1". www.standard.co.uk. Archived from the original on 21 May 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- "Recruitment: conscripts and volunteers during World War One". The British Library. Archived from the original on 17 May 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- "United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland – British Empire | NZHistory, New Zealand history online". nzhistory.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 21 May 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- "The Commonwealth and the First World War". www.nam.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 27 July 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- "French Army and the First World War". Spartacus Educational. Archived from the original on 23 March 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- "War Losses (Ottoman Empire/Middle East)". encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net. Archived from the original on 21 May 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- Alexander, Caroline. "The Shock of War". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- "What happened to the 8 million people who were disabled during WW1?". HistoryExtra. 14 August 2020. Archived from the original on 4 March 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- Scott, A. O. (20 June 2014). "A War to End All Innocence". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 21 May 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- "The Lost Generation: Who They Are and Where The Name Came From". FamilySearch Blog. 7 April 2020. Archived from the original on 30 August 2020. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- Rowbotham, Shiela (11 November 2018). "Women and the First World War: a taste of freedom". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- "Women in World War I". National Museum of American History. Archived from the original on 31 October 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- "Women's Mobilization for War (France)". encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net. Archived from the original on 21 May 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- "War Widows". encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net. Archived from the original on 3 May 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- "How the First World War affected families (War Widows)". www.mylearning.org. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- "Widows and Orphans". www.encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on 8 June 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- "How the First World War affected families (A Generation of 'Surplus Women')". www.mylearning.org. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- "Women's Suffrage by Country". www.infoplease.com. Archived from the original on 9 March 2017. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- Mackrell, Judith (5 February 2018). "The 1920s: 'Young women took the struggle for freedom into their personal lives". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- Pruitt, Sarah (17 September 2018). "How Flappers of the Roaring Twenties Redefined Womanhood". HISTORY. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- "First World War | Aftermath (outside the British empire)". www.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- "The National Archives | Exhibitions & Learning online | First World War | Aftermath (Britain after the War)". www.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- "The National Archives | Exhibitions & Learning online | First World War | Aftermath (British empire)". www.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- Craig, Ruth (10 November 2018). "Why Did the 1918 Flu Kill So Many Otherwise Healthy Young Adults?". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on 22 May 2021. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- Marc Moscato, Brains, Brilliancy, Bohemia: Art & Politics in Jazz-Age Chicago (2009)

- Anton Gill, A Dance Between Flames: Berlin Between the Wars (1994).

- David Robinson, Hollywood in the Twenties (1968)

- David Wallace, Capital of the World: A Portrait of New York City in the Roaring Twenties (2011)

- Hall, Lesley A. (1996). "Impotent ghosts from no man's land, flappers' boyfriends, or crypto‐patriarchs? Men, sex and social change in 1920s Britain". Social History. 21 (1): 54–70. doi:10.1080/03071029608567956.

- Jody Blake, Le Tumulte Noir: modernist art and popular entertainment in jazz-age Paris, 1900–1930 (1999)

- Jack Lindsay, The roaring twenties: literary life in Sydney, New South Wales in the years 1921-6 (1960)

- "Great Depression | Definition, History, Dates, Causes, Effects, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 9 May 2015. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- Seagrave, Sterling (5 February 2007). "post Feb 5 2007, 03:15 pm". The Education Forum. Archived from the original on 13 June 2008. Retrieved 13 June 2008.

Americans think of WW2 in Asia as having begun with Pearl Harbor, the British with the fall of Singapore, and so forth. The Chinese would correct this by identifying the Marco Polo Bridge incident as the start, or the Japanese seizure of Manchuria earlier.

- Vaughan, David (9 October 2008). "How the power of radio helped the Nazis to seize Europe". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 12 August 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- Konkel, Lindsey (19 April 2018). "Life for the Average Family During the Great Depression". HISTORY. Archived from the original on 29 June 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- Buck, George (2006). "The First Wave: The Beginnings of Radio in Canadian Distance Education" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- Dennis, Peter; et al. (2008). "Volunteer Defence Corps". The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History (Second ed.). Melbourne: Oxford University Press Australia & New Zealand. pp. 558–559. ISBN 978-0-19-551784-2.

- Kershaw, Ian (2001). Hitler: 1936–1945, Nemesis. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 713–714. ISBN 978-0-39332-252-1.

- Wells, Anne Sharp (2014) Historical Dictionary of World War II: The War against Germany and Italy. Rowman & Littlefield Publishing. p. 7.

- "The First World War generation - later lives". www.natwestgroupremembers.com. Archived from the original on 8 June 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- Cullen, Stephen M. "Bill Nighy fronts new Dad's Army, but don't forget the real Home Guard". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 5 June 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- Hasegawa, Tsuyoshi (2007). The end of the Pacific war: Reappraisals. Stanford University Press. pp. 75–77. ISBN 978-0-8047-5427-9. Archived from the original on 5 June 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- Schweitzer, Mary M. (1980). "World War II and Female Labor Force Participation Rates". The Journal of Economic History. 40 (1): 89–95. doi:10.1017/S0022050700104577. ISSN 0022-0507. JSTOR 2120427. S2CID 154770243. Archived from the original on 5 June 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- Carruthers, Susan L. (1990). "'Manning the Factories': Propaganda and Policy on the Employment of Women, 1939–1947". History. 75 (244): 232–256. doi:10.1111/j.1468-229X.1990.tb01516.x. JSTOR 24420973.

- Campbell, D'Ann (1 April 1993). "Women in combat: The World War II experience in the United States, Great Britain, Germany, and the Soviet Union". The Journal of Military History. 57 (2): 301–323. doi:10.2307/2944060. JSTOR 2944060. ProQuest 1296724766.

- Taylor, Alan. "World War II: Women at War". www.theatlantic.com. Archived from the original on 4 June 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Gendall, Murray; Siegall, Jacob (July 1992). "Trends in retirement age by sex, 1950 to 2005" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 June 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- "Workers retiring earlier than in 1950". BBC News. 7 September 2017. Archived from the original on 8 June 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- "Life expectancy in the USA, 1900-98". u.demog.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 21 June 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- "United Kingdom: life expectancy 1765-2020". Statista. Archived from the original on 22 April 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- "France Life Expectancy 1950-2021". www.macrotrends.net. Archived from the original on 19 July 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- "Germany: life expectancy 1875-2020". Statista. Archived from the original on 14 May 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- "Ninety years of change in life expectancy". www150.statcan.gc.ca. 25 November 2013. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- Politi, Daniel (22 April 2018). "The Last Known Person Born in the 19th Century Dies in Japan at 117". Slate Magazine. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- Blackmore, David (7 February 2012). "Norfolk First World War Veteran Dies". EDP24. Archived from the original on 3 October 2016. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- Carman, Gerry (6 May 2011). "Last man who served in two world wars dies, 110". The Age. Archived from the original on 8 May 2011. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

- "Time use of millennials v. non-millennials". 8 April 2021. Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- Hemingway, Ernest (1996). A Moveable Feast. New York: Scribner. ISBN 978-0-684-82499-4.

- Mellow, James R. (1991). Charmed Circle: Gertrude Stein and Company. New York: Houghton Mifflin. p. 273. ISBN 978-0-395-47982-7.

- Mellow, James R. (1992). Hemingway: A Life Without Consequences. New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-37777-2.

- Baker, Carlos (1972). Hemingway, the writer as artist. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-01305-3.

- "Hemingway, the Fitzgeralds, and the Lost Generation: An Interview with Kirk Curnutt | The Hemingway Project". www.thehemingwayproject.com. Archived from the original on 29 March 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- "Lost Generation | Great Writers Inspire". writersinspire.org. Archived from the original on 9 April 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- "American Lost Generation". InterestingArticles.com. Archived from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- Lapsansky-Werner, Emma J. United States History: Modern America. Boston, MA: Pearson Learning Solutions, 2011. Print. Page 238

- Esguerra, Geolette (9 October 2018). "Sartre was here: 17 cafés where the literary gods gathered". ABS-CBN News. Archived from the original on 12 March 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- Thompson, Rachel (25 July 2014). "A Literary Tour of Paris". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 13 May 2017. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- "Obituaries: Henry Strater, 91; Artist at Center of Lost Generation". Los Angeles Times. 24 December 1987.

- Monk, Craig (2010). Writing the Lost Generation: Expatriate Autobiography and American Modernism. University of Iowa Press.

Further reading

- Dolan, Marc. Modern Lives: A Cultural Re-Reading of the "Lost Generation" (Purdue University Press, 1996).

- Doyle, Barry M., "Urban Liberalism and the 'lost generation': Politics and middle-class culture in Norwich, 1900–1935". Historical Journal 38.3 (1995): 617–634. in Great Britain.

- Fitch, Noel Riley (1985). Sylvia Beach and the Lost Generation: A History of Literary Paris in the Twenties and Thirties. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-30231-8.

- Green, Nancy L. "Expatriation, expatriates, and expats: The American transformation of a concept." American Historical Review 114.2 (2009): 307-328. online

- Hansen, Arlen J. Expatriate Paris: A Cultural and Literary Guide to Paris of the 1920s (2012) excerpt

- Kotin, Joshua, Clifford E. Wulfman, and Jesse McCarthy. "Mapping Expatriate Paris: A Digital Humanities Project." Princeton University Library Chronicle 77.1-2 (2016): 17-34. online

- McAuliffe, Mary. When Paris Sizzled: The 1920s Paris of Hemingway, Chanel, Cocteau, Cole Porter, Josephine Baker, and Their Friends (2019) excerpt

- Meyers, Jeffrey (1985). Hemingway: A Biography. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-42126-0.

- Monk, Craig. Writing the Lost Generation: Expatriate Autobiography and American Modernism (University of Iowa Press, 2010).

- Winter, Jay M., "Britain's 'Lost Generation' of the First World War". Population Studies 31.3 (1977): 449–466. online, covers the statistical and demographic history.