Toledot

Toledot, Toldot, Toldos, or Toldoth (תּוֹלְדֹת—Hebrew for "generations" or "descendants," the second word and the first distinctive word in the parashah) is the sixth weekly Torah portion (פָּרָשָׁה, parashah) in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading. The parashah tells of the conflict between Jacob and Esau, Isaac's passing off his wife Rebekah as his sister, and Isaac's blessing of his sons.

It constitutes Genesis 25:19–28:9. The parashah is made up of 5,426 Hebrew letters, 1,432 Hebrew words, 106 verses, and 173 lines in a Torah Scroll (סֵפֶר תּוֹרָה, Sefer Torah).[1] Jews read it the sixth Sabbath after Simchat Torah, generally in November, or rarely in early December.[2]

Readings

In traditional Sabbath Torah reading, the parashah is divided into seven readings, or עליות, aliyot. In the Masoretic Text of the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible), Parashat Toledot has two "open portion" (פתוחה, petuchah) divisions (roughly equivalent to paragraphs, often abbreviated with the Hebrew letter פ (peh)). Parashat Toledot has three "closed portion" (סתומה, setumah) divisions (abbreviated with the Hebrew letter ס (samekh)), that further divide the second open portion. The first open portion divides the first reading. The second open portion spans the balance of the parashah. Two closed portion divisions further divide the fifth reading, setting apart the discussion of Esau's marriage to the two Hittite women.[3]

First reading—Genesis 25:19–26:5

In the first reading, Isaac was 40 years old when he married Rebekah, and when the couple proved unable to conceive, Isaac pleaded with God on Rebekah's behalf, and God allowed Rebekah to conceive.[4] As twins struggled in her womb, she inquired of God, who answered her that two separate nations were in her womb, one mightier than the other, and the older would serve the younger.[5] When Rebekah gave birth, the first twin emerged red and hairy, so they named him Esau, and his brother emerged holding Esau's heel, so they named him Jacob.[6] Isaac was 60 years old when they were born.[7] Esau became a skillful hunter and outdoorsman, but Jacob remained a mild man and camp-bound.[8] Isaac favored Esau for his game, but Rebekah favored Jacob.[9] Once when Jacob was cooking, Esau returned to the camp famished and demanded some of Jacob's red stew.[10] Jacob demanded that Esau first sell him his birthright, and Esau did so with an oath, spurning his birthright.[11] The first open portion ends here with the end of chapter 25.[12]

As the reading continues in chapter 26, another famine struck the land, and Isaac went to the house of the Philistine King Abimelech in Gerar.[13] God told Isaac not to go down to Egypt, but to stay in the land that God would show him, for God would remain with him, bless him, and assign the land to him and his numerous heirs, as God had sworn to Abraham, who had obeyed God and kept God's commandments.[14] The first reading ends here.[15]

Second reading—Genesis 26:6–12

In the second reading, Isaac settled in Gerar, and when the men of Gerar asked Isaac about his beautiful wife, he said that she was his sister out of fear that the men might kill him on account of her.[16] But looking out of the window, Abimelech saw Isaac fondling Rebekah, and Abimelech summoned Isaac to complain that Isaac had called her his sister.[17] Isaac explained that he had done so to save his life.[18] Abimelech complained that one of the people might have lain with her, and Isaac would have brought guilt upon the Philistines, and Abimelech charged the people not to molest Isaac or Rebekah, on pain of death.[19] God blessed Isaac, who reaped bountiful harvests.[20] The second reading ends here.[21]

Third reading—Genesis 26:13–22

In the third reading, Isaac grew very wealthy, to the envy of the Philistines.[22] The Philistines stopped up all the wells that Abraham's servants had dug, and Abimelech sent Isaac away, for his household had become too big.[23] So Isaac left to settle in the wadi of Gerar, where he dug anew the wells that Abraham's servants had dug and called them by the same names that his father had.[24] But when Isaac's servants dug two new wells, the herdsmen of Gerar quarreled with Isaac's herdsmen and claimed them for their own, so Isaac named those wells Esek and Sitnah.[25] Isaac moved on and dug a third well, and they did not quarrel over it, so he named it Rehoboth.[26] The third reading ends here.[27]

Fourth reading—Genesis 26:23–29

In the fourth reading, Isaac went to Beersheba, and that night God appeared to Isaac, telling Isaac not to fear, for God was with him, and would bless him and increase his offspring for Abraham's sake.[28] So Isaac built an altar and invoked the Lord by name.[29] And Isaac pitched his tent there and his servants began digging a well.[29] Then Abimelech, Ahuzzath his councilor, and Phicol his general came to Isaac, and Isaac asked them why they had come, since they had driven Isaac away.[30] They answered that they now recognized that God had been with Isaac, and sought a treaty that neither would harm the other.[31] The fourth reading ends here.[32]

Fifth reading—Genesis 26:30–27:27

In the fifth reading, Isaac threw a feast for the Philistines, and the next morning, they exchanged oaths and the Philistines departed from him in peace.[33] Later in the day, Isaac's servants told him that they had found water, and Isaac named the well Shibah, so that place became known as Beersheba.[34] A closed portion ends here.[35]

In the continuation of the reading, when Esau was 40 years old, he married two Hittite women, Judith and Basemath, causing bitterness for Isaac and Rebekah.[36] Another closed portion ends here with the end of chapter 26.[35]

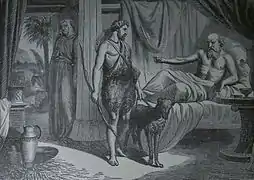

As the reading continues in chapter 27, when Isaac was old and his sight had dimmed, he called Esau and asked him to hunt some game and prepare a dish, so that Isaac might give him his innermost blessing before he died.[37] Rebekah had been listening, and when Esau departed, she instructed Jacob to fetch her two choice kids so that she might prepare a dish that Jacob could take to Isaac and receive his blessing.[38] Jacob complained to Rebekah that since Esau was hairy, Isaac might touch him, discover him to be a trickster, and curse him.[39] But Rebekah called the curse upon herself, insisting that Jacob do as she directed.[40] So Jacob got the kids, and Rebekah prepared a dish, had Jacob put on Esau's best clothes, and covered Jacob's hands and neck with the kid's skins.[41] When Jacob went to Isaac, he asked which of his sons had arrived, and Jacob said that he was Esau and asked for Isaac's blessing.[42] Isaac asked him how he had succeeded so quickly, and he said that God had granted him good fortune.[43] Isaac asked Jacob to come closer that Isaac might feel him to determine whether he was really Esau.[44] Isaac felt him and wondered that the voice was Jacob's, but the hands were Esau's.[45] Isaac questioned if it was really Esau, and when Jacob assured him, Isaac asked for the game and Jacob served him the kids and wine.[46] Isaac bade his son to come close and kiss him, and Isaac smelled his clothes, remarking that he smelled like the fields.[47] The fifth reading ends here.[48]

Sixth reading—Genesis 27:28–28:4

In the sixth reading, Isaac blessed Jacob, asking God to give him abundance, make peoples serve him, make him master over his brothers, curse those who cursed him, and bless those who blessed him.[49] Just as Jacob left, Esau returned from the hunt, prepared a dish for Isaac, and asked Isaac for his blessing.[50] Isaac asked who he was, and Esau said that it was he.[51] Isaac trembled and asked who it was then who had served him, received his blessing, and now must remain blessed.[52] Esau burst into sobbing, and asked Isaac to bless him too, but Isaac answered that Jacob had taken Esau's blessing with guile.[53] Esau asked whether Jacob had been so named that he might supplant Esau twice, first taking his birthright and now his blessing.[54] Esau asked Isaac whether he had not reserved a blessing for Esau, but Isaac answered that he had made Jacob master over him and sustained him with grain and wine, and asked what, then, he could still do for Esau.[55] Esau wept and pressed Isaac to bless him, too, so Isaac blessed him to enjoy the fat of the earth and the dew of heaven, to live by his sword and to serve his brother, but also to break his yoke.[56] Esau harbored a grudge against Jacob, and told himself that he would kill Jacob upon Isaac's death.[57] When Esau's words reached Rebekah, she told Jacob to flee to Haran and her brother Laban and remain there until Esau's fury subsided and Rebekah fetched him from there, so that Rebekah would not lose both sons in one day.[58] Rebekah told Isaac her disgust with the idea that Jacob might marry a Hittite woman, so Isaac sent for Jacob, blessed him, and instructed him not to take a Canaanite wife, but to go to Padan-aram and the house of Bethuel to take a wife from among Laban's daughters.[59] And Isaac blessed Jacob with fertility and the blessing of Abraham, that he might possess the land that God had assigned to Abraham.[60] The sixth reading ends here.[61]

Seventh reading—Genesis 28:5–9

In the seventh reading, when Esau saw that Isaac had blessed Jacob and charged him not to take a Canaanite wife, Esau realized that the Canaanite women displeased Isaac, and Esau married Ishmael's daughter Mahalath.[62] The seventh reading, a closed portion, the closing maftir (מפטיר) reading of Genesis 28:7–9, and the parashah all end here.[63]

Readings according to the triennial cycle

Jews who read the Torah according to the triennial cycle of Torah reading read the parashah according to the following schedule:[64]

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2022, 2025, 2028 . . . | 2023, 2026, 2029 . . . | 2024, 2027, 2030 . . . | |

| Reading | 25:19–26:22 | 26:23–27:27 | 27:28–28:9 |

| 1 | 25:19–22 | 26:23–29 | 27:28–30 |

| 2 | 25:23–26 | 26:30–33 | 27:31–33 |

| 3 | 25:27–34 | 26:34–27:4 | 27:34–37 |

| 4 | 26:1–5 | 27:5–13 | 27:38–40 |

| 5 | 26:6–12 | 27:14–17 | 27:41–46 |

| 6 | 26:13–16 | 27:18–23 | 28:1–4 |

| 7 | 26:17–22 | 27:24–27 | 28:5–9 |

| Maftir | 26:19–22 | 27:24–27 | 28:7–9 |

In inner-biblical interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these Biblical sources:[65]

Genesis chapter 25

Genesis 25:26 reports that Rebekah "went to inquire (לִדְרֹשׁ, lidrosh) of the Lord." 1 Samuel 9:9 explains, "Formerly in Israel, when a man went to inquire (לִדְרוֹשׁ, lidrosh) of God, he said: 'Come and let us go to the seer'; for he who is now called a prophet was formerly called a seer."

Hosea taught that God once punished Jacob for his conduct, requiting him for his deeds, including that (as reported in Genesis 25:26) in the womb he tried to supplant his brother.[66]

Genesis chapter 26

In Genesis 26:4, God reminded Isaac that God had promised Abraham that God would make his heirs as numerous as the stars. In Genesis 15:5, God promised that Abraham's descendants would as numerous as the stars of heaven. Similarly, in Genesis 22:17, God promised that Abraham's descendants would as numerous as the stars of heaven and the sands on the seashore. In Genesis 32:13, Jacob reminded God that God had promised that Jacob's descendants would be as numerous as the sands. In Exodus 32:13, Moses reminded God that God had promised to make the Patriarch's descendants as numerous as the stars. In Deuteronomy 1:10, Moses reported that God had multiplied the Israelites until they were then as numerous as the stars. In Deuteronomy 10:22, Moses reported that God had made the Israelites as numerous as the stars. And Deuteronomy 28:62 foretold that the Israelites would be reduced in number after having been as numerous as the stars.

God's reference to Abraham as "my servant" (עַבְדִּי, avdi) in Genesis 26:24 is echoed in God's application of the same term to Moses,[67] Caleb,[68] David,[69] Isaiah,[70] Eliakim the son of Hilkiah,[71] Israel,[72] Nebuchadnezzar,[73] Zerubbabel,[74] the Branch,[75] and Job.[76]

Genesis chapter 27–28

In Genesis 27–28, Jacob receives three blessings: (1) by Isaac when Jacob is disguised as Esau in Genesis 27:28–29, (2) by Isaac when Jacob is departing for Haran in Genesis 28:3–4, and (3) by God in Jacob's dream at Bethel in Genesis 28:13–15. Whereas the first blessing is one of material wellbeing and dominance, only the second and third blessings convey fertility and the Land of Israel. The first and the third blessings explicitly designate Jacob as the conveyor of blessing, although arguably the second blessing does that as well by giving Jacob "the blessing of Abraham." (See Genesis 12:2–3.) Only the third blessing vouchsafes God's Presence with Jacob.

| Genesis 27:28–29

Isaac Blessing the Disguised Jacob |

Genesis 28:3–4

Isaac Blessing Jacob on Departure |

Genesis 28:13–15

God Blessing Jacob at Bethel |

|---|---|---|

| 28 God give you of the dew of heaven, and of the fat places of the earth, and plenty of corn and wine. 29 Let peoples serve you, and nations bow down to you. Be lord over your brethren, and let your mother's sons bow down to you. Cursed be everyone who curses you, and blessed be everyone who blesses you. | 3 God Almighty bless you, and make you fruitful, and multiply you, that you may be a congregation of peoples; 4 and give you the blessing of Abraham, to you, and to your seed with you; that you may inherit the land of your sojournings, which God gave to Abraham. | 13 I am the Lord, the God of Abraham your father, and the God of Isaac. The land on which you lie, to you will I give it, and to your seed. 14 And your seed shall be as the dust of the earth, and you shall spread abroad to the west, and to the east, and to the north, and to the south. And in you and in your seed shall all the families of the earth be blessed. 15 And, behold, I am with you, and will keep you wherever you go, and will bring you back into this land; for I will not leave you, until I have done that of which I have spoken to you. |

In classical rabbinic interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these rabbinic sources from the era of the Mishnah and the Talmud:[77]

Genesis chapter 25

Rabbi Judah taught that Rebekah was barren for 20 years. After 20 years, Isaac took Rebekah to Mount Moriah, to the place where he had been bound, and he prayed on her behalf concerning conception, and God was entreated, as Genesis 25:21 says, "And Isaac entreated the Lord."[78]

Rava argued that one may deduce from Isaac's example that a man may remain for 20 years with an infertile wife. For of Isaac, Genesis 25:20 says, "And Isaac was 40 years old when he took Rebekah . . . to be his wife," and Genesis 25:26 says, "And Isaac was 60 years old when she bore them" (which shows that Isaac waited 20 years). Rav Nachman replied that Isaac was infertile (and he knew that the couple was childless because of him). Rabbi Isaac deduced that Isaac was infertile from Genesis 25:21, which says, "And Isaac entreated the Lord opposite his wife." Rabbi Isaac taught that Genesis 25:21 does not say "for his wife" but "opposite his wife." Rabbi Isaac deduced from this that both were barren (as he had to pray for himself as well as her). The Gemara countered that if this were so, then Genesis 25:21 should not read, "And the Lord let Himself be entreated by him," but rather should read, "And the Lord let Himself be entreated by them" (as Isaac's prayer was on behalf of them both). But the Gemara explained that Genesis 25:21 reads, "And the Lord let Himself be entreated by him," because the prayer of a righteous person who is the child of a righteous person (Isaac son of Abraham) is even more effective than the prayer of a righteous person who is the child of a wicked person (Rebekah daughter of Bethuel). Rabbi Isaac taught that the Patriarchs and Matriarchs were infertile because God longs to hear the prayer of the righteous.[79]

Noting that the three-letter root עתר used in Genesis 25:21 can mean either "entreat" or "pitchfork," Rabbi Eleazar (or others say Rabbi Isaac or Resh Lakish) taught that the prayers of the righteous are like a pitchfork. Just as the pitchfork turns the grain from place to place in the barn, so the prayers of the righteous turn the mind of God from the attribute of harshness to that of mercy.[80]

.jpg.webp)

Rabbi Joḥanan interpreted the words "And Isaac entreated (וַיֶּעְתַּר, vaye'tar) the Lord" in Genesis 25:21 to mean that Isaac poured out petitions in abundance (as in Aramaic, עתר, 'tar, means "wealth"). The Midrash taught that the words "for (לְנֹכַח, lenokhach) his wife" taught that Isaac prostrated himself in one spot and Rebekah in another (opposite him), and he prayed to God that all the children whom God would grant him would come from this righteous woman, and Rebekah prayed likewise. Reading the words, "Because she was barren," in Genesis 25:21, Rabbi Judan said in the name of Resh Lakish that Rebekah lacked an ovary, whereupon God fashioned one for her. And reading the words, "And the Lord let Himself be entreated (וַיֵּעָתֶר, vayei'ater) of him," in Genesis 25:21, Rabbi Levi compared this to the son of a king who was digging through to his father to receive a pound of gold from him, and thus the king dug from inside while his son dug from outside.[81]

.jpg.webp)

The Pesikta de-Rav Kahana taught that Rebekah was one of seven barren women about whom Psalm 113:9 says (speaking of God), "He . . . makes the barren woman to dwell in her house as a joyful mother of children." The Pesikta de-Rav Kahana also listed Sarah, Rachel, Leah, Manoah's wife, Hannah, and Zion. The Pesikta de-Rav Kahana taught that the words of Psalm 113:9, "He . . . makes the barren woman to dwell in her house," apply to Rebekah, for Genesis 25:21 reports that "Isaac entreated the Lord for his wife, because she was barren." And the words of Psalm 113:9, "a joyful mother of children," apply to Rebekah, as well, for Genesis 25:21 also reports that "the Lord let Himself be entreated of him, and Rebekah his wife conceived."[82]

.jpg.webp)

Rabbi Berekiah and Rabbi Levi in the name of Rabbi Ḥama ben Ḥaninah taught that God answered Isaac's prayer for children in Genesis 25:21, rather than the prayer of Rebekah's family in Genesis 24:60. Rabbi Berekiah in Rabbi Levi's name read Job 29:13 to say, "The blessing of the destroyer (אֹבֵד, oved) came upon me," and interpreted "The blessing of the destroyer (אֹבֵד, oved)" to allude to Laban the Syrian. Rabbi Berekiah in Rabbi Levi's name thus read Deuteronomy 26:5 to say, "An Aramean (Laban) sought to destroy (אֹבֵד, oved) my father (Jacob)." (Thus Laban sought to destroy Jacob by, perhaps among other things, cheating Jacob out of payment for his work, as Jacob recounted in Genesis 31:40–42. This interpretation thus reads אֹבֵד, oved, as a transitive verb.) Rabbi Berekiah and Rabbi Levi in the name of Rabbi Ḥama ben Ḥaninah thus explained that Rebekah was remembered with the blessing of children only after Isaac prayed for her, so that the heathens in Rebekah's family might not say that their prayer in Genesis 24:60 caused that result. Rather, God answered Isaac's prayer, as Genesis 25:21 reports, "And Isaac entreated the Lord for his wife . . . and his wife Rebekah conceived."[83]

It was taught in Rabbi Nehemiah's name that Rebekah merited that the twelve tribes should spring directly from her.[84]

Reading the words of Genesis 25:22, "and the children struggled together with in her," a Midrash taught that they sought to run within her. When she stood near synagogues or schools, Jacob struggled to come out, while when she passed idolatrous temples, Esau struggled to come out.[84]

Reading the words, "and she went to inquire of the Lord," in Genesis 25:22, a Midrash wondered how Rebekah asked God about her pregnancy, and whether there were synagogues and houses of study in those days. The Midrash concluded that Rebekah went to the school of Shem and Eber to inquire. The Midrash deduced that this teaches that to visit a Sage is like visiting the Divine Presence.[84]

Reading Genesis 25:23, "the Lord said to her," Rabbi Iddi taught that God spoke to her through the medium of an angel.[85] Rabbi Ba bar Kahana said that God’s word came to her through an intermediary.[86] Rabbi Haggai said in Rabbi Isaac's name that Rebekah was a prophet, as were all of the matriarchs.[87]

The Rabbis of the Talmud read Edom to stand for Rome. Thus, Rav Nahman bar Isaac interpreted the words, "and the one people shall be stronger than the other people," in Genesis 25:23 to teach that at any one time, one of Israel and Rome will be ascendant, and the other will be subjugated.[88]

Reading the words, "And Esau was a cunning hunter," in Genesis 25:27, a Midrash taught that Esau ensnared people by their words. Reading the words, "and Jacob was a quiet man, dwelling in tents," the Midrash taught that Jacob dwelt in two tents, the academy of Shem and the academy of Eber. And reading the words, "And Rebekah loved Jacob," in Genesis 25:28, the Midrash taught that the more Rebekah heard Jacob's voice (engaged in study), the stronger her love grew for him.[89]

Rabbi Ḥaninah taught that Esau paid great attention to his parent (horo), his father, whom he supplied with meals, as Genesis 25:28 reports, "Isaac loved Esau, because he ate of his venison." Rabbi Samuel the son of Rabbi Gedaliah concluded that God decided to reward Esau for this. When Jacob offered Esau gifts, Esau answered Jacob in Genesis 33:9, "I have enough (רָב, rav); do not trouble yourself." So God declared that with the same expression that Esau thus paid respect to Jacob, God would command Jacob's descendants not to trouble Esau's descendants, and thus God told the Israelites in Deuteronomy 2:3, "You have circled this mountain (הָר, har) long enough (רַב, rav)."[90]

Bar Kappara and Rabbi Jose bar Patros referred to Genesis 25:28 to explain why, in Genesis 46:1, just before heading down to Egypt, Jacob "offered sacrifices to the God of his father Isaac," and not to the God of Abraham and Isaac. Bar Kappara discussed the question with Rabbi Jose bar Patros. One of them said that Jacob declared that as Isaac had been eager for his food (for, as Genesis 25:28 reports, Isaac loved Esau because Esau brought Isaac venison), so Jacob was eager for his food (and thus was headed to Egypt to avoid the famine). The other explained that as Isaac had distinguished between his sons (as Genesis 25:28 reports, loving Esau more than Jacob), so Jacob would distinguish among his sons (going to Egypt for Joseph's account alone). But then Jacob noted on reconsideration that Isaac was responsible for only one soul, whereas Jacob was responsible for 70 souls.[91]

A Tanna taught in a Baraita that the day recounted in Genesis 25:29–34 on which Esau spurned his birthright was also the day on which Abraham died, and Jacob was cooking lentils to comfort Isaac. In the Land of Israel, they taught in the name of Rabbah bar Mari that it was appropriate to cook lentils because just as the lentil has no mouth (no groove like other legumes), so the mourner has no mouth to talk but sits silently. Others explained that just as the lentil is round, so mourning comes round to all people.[92]

Rabbi Joḥanan taught that Esau committed five sins on the day recounted in Genesis 25:29–34. Rabbi Joḥanan deduced from the similar use of the words "the field" in Genesis 25:29 and in connection with the betrothed maiden in Deuteronomy 22:27 that Esau dishonored a betrothed maiden. Rabbi Joḥanan deduced from the similar use of the word "faint" in Genesis 25:29 and in connection with murderers in Jeremiah 4:31 that Esau committed a murder. Rabbi Joḥanan deduced from the similar use of the word "this" in Genesis 25:32 and in the words "This is my God" in Exodus 15:2 that Esau denied belief in God. Rabbi Joḥanan deduced from Esau's words, "Behold, I am on the way to die," in Genesis 25:32 that Esau denied the resurrection of the dead. And for Esau's fifth sin, Rabbi Joḥanan cited the report of Genesis 25:34 that "Esau despised his birthright."[92]

Genesis chapter 26

A Midrash cited Genesis 26:1 to show that there is double rejoicing in the case of a righteous one who is the child of a righteous one.[93] The Mishnah and Tosefta deduced from Genesis 26:5 that Abraham kept the entire Torah even before it was revealed.[94]

The Tosefta deduced from the contrast between the plenty indicated in Genesis 24:1 and the famine indicated in Genesis 26:1 that God gave the people food and drink and a glimpse of the world to come while the righteous Abraham was alive, so that the people might understand what they had lost when he was gone.[95] The Tosefta reported that when Abraham was alive, the wells gushed forth water, but the Philistines filled the wells with earth (as reported in Genesis 26:15), for after Abraham died the wells no longer gushed forth water, and the Philistines filled them so that they would not provide cover for invaders. But when Isaac came along, the wells gushed water again (as indicated in Genesis 26:18–19) and there was plenty again (as indicated in Genesis 26:12)[96]

Interpreting God's command to Isaac in Genesis 26:2 not to go to Egypt, Rabbi Hoshaya taught that God told Isaac that he was (by virtue of his near sacrifice in Genesis 22) a burnt-offering without blemish, and as a burnt offering became unfit if it was taken outside of the Temple grounds, so would Isaac become unfit if he went outside of the Promised Land.[97]

Rabbi Eliezer taught that the five Hebrew letters of the Torah that alone among Hebrew letters have two separate shapes (depending whether they are in the middle or the end of a word)—צ פ נ מ כ (Kh, M, N, P, Z)—all relate to the mystery of the redemption, including to Isaac's redemption from the Philistines in Genesis 26:16. With the letter kaph (כ), God redeemed Abraham from Ur of the Chaldees, as in Genesis 12:1, God says, "Get you (לֶךְ-לְךָ, lekh lekha) out of your country, and from your kindred . . . to the land that I will show you." With the letter mem (מ), Isaac was redeemed from the land of the Philistines, as in Genesis 26:16, the Philistine king Abimelech told Isaac, "Go from us: for you are much mightier (מִמֶּנּוּ, מְאֹד, mimenu m'od) than we." With the letter nun (נ), Jacob was redeemed from the hand of Esau, as in Genesis 32:12, Jacob prayed, "Deliver me, I pray (הַצִּילֵנִי נָא, hazileini na), from the hand of my brother, from the hand of Esau." With the letter pe (פ), God redeemed Israel from Egypt, as in Exodus 3:16–17, God told Moses, "I have surely visited you, (פָּקֹד פָּקַדְתִּי, pakod pakadeti) and (seen) that which is done to you in Egypt, and I have said, I will bring you up out of the affliction of Egypt." With the letter tsade (צ), God will redeem Israel from the oppression of the kingdoms, and God will say to Israel, I have caused a branch to spring forth for you, as Zechariah 6:12 says, "Behold, the man whose name is the Branch (צֶמַח, zemach); and he shall grow up (יִצְמָח, yizmach) out of his place, and he shall build the temple of the Lord." These letters were delivered to Abraham. Abraham delivered them to Isaac, Isaac delivered them to Jacob, Jacob delivered the mystery of the Redemption to Joseph, and Joseph delivered the secret of the Redemption to his brothers, as in Genesis 50:24, Joseph told his brothers, "God will surely visit (פָּקֹד יִפְקֹד, pakod yifkod) you." Jacob's son Asher delivered the mystery of the Redemption to his daughter Serah. When Moses and Aaron came to the elders of Israel and performed signs in their sight, the elders told Serah. She told them that there is no reality in signs. The elders told her that Moses said, "God will surely visit (פָּקֹד יִפְקֹד, pakod yifkod) you" (as in Genesis 50:24). Serah told the elders that Moses was the one who would redeem Israel from Egypt, for she heard (in the words of Exodus 3:16), "I have surely visited (פָּקֹד פָּקַדְתִּי, pakod pakadeti) you." The people immediately believed in God and Moses, as Exodus 4:31 says, "And the people believed, and when they heard that the Lord had visited the children of Israel."[98]

Reading Genesis 26:12, “And Isaac sowed in that land, and found in that year a hundredfold (שְׁעָרִים, she'arim),” a Midrash taught that the words, “a hundred שְׁעָרִים, she'arim” indicate that they estimated it, but it produced a hundred times the estimate, for blessing does not rest upon that which is weighed, measured, or counted. They measured solely on account of the tithes.[99]

Rabbi Dosetai ben Yannai said in the name of Rabbi Meir that when God told Isaac that God would bless him for Abraham's sake (in Genesis 26:24), Isaac interpreted that one earns a blessing only through one's actions, and he arose and sowed, as reported in Genesis 26:12.[100]

A Midrash reread Genesis 26:26, "Then Abimelech went to him from Gerar (מִגְּרָר, mi-gerar)," to say that Abimelech came "wounded" (מגורר, megorar), teaching that ruffians entered Abimelech's house and assailed him all night. Alternatively, the Midrash taught that he came "scraped" (מְגוּרָד, megurad), teaching that eruptions broke out on Abimelech and he kept scraping himself.[101]

The Sifre cited Isaac's reproof of Abimelech, Ahuzzath, and Phicol in Genesis 26:27 as an example of a tradition of admonition near death. The Sifre read Deuteronomy 1:3–4 to indicate that Moses spoke to the Israelites in rebuke. The Sifre taught that Moses rebuked them only when he approached death, and the Sifre taught that Moses learned this lesson from Jacob, who admonished his sons in Genesis 49 only when he neared death. The Sifre cited four reasons why people do not admonish others until the admonisher nears death: (1) so that the admonisher does not have to repeat the admonition, (2) so that the one rebuked would not suffer undue shame from being seen again, (3) so that the one rebuked would not bear ill will to the admonisher, and (4) so that the one may depart from the other in peace, for admonition brings peace. The Sifre cited as further examples of admonition near death: (1) when Abraham reproved Abimelech in Genesis 21:25, (2) when Isaac reproved Abimelech, Ahuzzath, and Phicol in Genesis 26:27, (3) when Joshua admonished the Israelites in Joshua 24:15, (4) when Samuel admonished the Israelites in 1 Samuel 12:34–35, and (5) when David admonished Solomon in 1 Kings 2:1. In Isaac's case, the Sifre read the report of Genesis 26:31 to teach that Abimelech, Ahuzzath, and Phicol made peace with Isaac because Isaac had justly reproved them.[102]

Reading the verb "to see" repeated (רָאוֹ רָאִינוּ, ra'o ra'iynu) in the passage "We saw plainly" in Genesis 26:28, a Midrash taught that Abimelech and his party had seen two things—Isaac's deeds and the deeds of his parents.[103]

A Midrash taught that Abimelech first sent Phicol, the captain of his host, but he was unable to pacify Isaac. Then Abimelech sent his friend Ahuzzath, but Isaac still remained unpacified. When Abimelech then went himself, Isaac allowed himself to be appeased. Hence, the Sages taught that one need not ask another's forgiveness more than three times. If the other does not forgive the third time, then the other becomes the wrongdoer.[104]

The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer told how Isaac made a covenant with the Philistines, when he sojourned there. Isaac noticed that the Philistines turned their faces away from him. So Isaac left them in peace, and Abimelech and his magnates came after him. Paraphrasing Genesis 26:27, the Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer told that Isaac asked them why they came to him, after having turned aside their faces from him. Paraphrasing Genesis 26:28, the Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer told that the Philistines replied that they knew that God would give the Land of Israel to Isaac's descendants, and thus they asked him to make a covenant with them that his descendants would not take possession of the land of the Philistines. And so Isaac made a covenant with them. He cut off one cubit of the bridle of the donkey upon which he was riding, and he gave it to them so that they might thereby have a sign of the covenant.[105]

Reading the report of Esau's marriage to two Hittite women in Genesis 26:34, a Midrash found signs of the duplicity of Esau and his spiritual descendants, the Romans. Rabbi Phinehas (and other say Rabbi Helkiah) taught in Rabbi Simon's name that Moses and Asaph (author of Psalm 80) exposed the Romans' deception. Asaph said in Psalm 80:14: "The boar of the wood ravages it." While Moses said in Deuteronomy 14:7–8: "you shall not eat of . . . the swine, because he parts the hoof but does not chew the cud." The Midrash explained that Scripture compares the Roman Empire to a swine, because when the swine lies down, it puts out its parted hoofs, as if to advertise that it is clean. And so the Midrash taught that the wicked Roman Empire robbed and oppressed, yet pretended to execute justice. So the Midrash taught that for 40 years, Esau would ensnare married women and violate them, yet when he reached the age of 40, he compared himself to his righteous father Isaac, telling himself that as his father Isaac was 40 years old when he married (as reported in Genesis 25:19), so he too would marry at the age of 40.[106]

Genesis chapter 27

Rabbi Ḥama bar Ḥaninah taught that our ancestors were never without a scholars' council. Abraham was an elder and a member of the scholars' council, as Genesis 24:1 says, "And Abraham was an elder (זָקֵן, zaken) well stricken in age." Eliezer, Abraham's servant, was an elder and a member of the scholars' council, as Genesis 24:2 says, "And Abraham said to his servant, the elder of his house, who ruled over all he had," which Rabbi Eleazar explained to mean that he ruled over—and thus knew and had control of—the Torah of his master. Isaac was an elder and a member of the scholars' council, as Genesis 27:1 says: "And it came to pass when Isaac was an elder (זָקֵן, zaken)." Jacob was an elder and a member of the scholars' council, as Genesis 48:10 says, "Now the eyes of Israel were dim with age (זֹּקֶן, zoken)." In Egypt they had the scholars' council, as Exodus 3:16 says, "Go and gather the elders of Israel together." And in the Wilderness, they had the scholars' council, as in Numbers 11:16, God directed Moses to "Gather . . . 70 men of the elders of Israel."[107]

Rabbi Eleazar taught that Isaac's blindness, reported in Genesis 27:1, was caused by his looking at the wicked Esau. But Rabbi Isaac taught that Abimelech's curse of Sarah caused her son Isaac's blindness. Rabbi Isaac read the words, "it is for you a covering (kesut) of the eyes," in Genesis 20:16 not as kesut, "covering," but as kesiyat, "blinding." Rabbi Isaac concluded that one should not consider a small matter the curse of even an ordinary person.[108] Alternatively, a Midrash interpreted the words "his eyes were dim from seeing" in Genesis 27:1 to teach that Isaac's eyesight dimmed as a result of his near sacrifice in Genesis 22, for when Abraham bound Isaac, the ministering angels wept, as Isaiah 33:7 says, "Behold, their valiant ones cry without, the angels of peace weep bitterly," and tears dropped from the angels' eyes into Isaac's, leaving their mark and causing Isaac's eyes to dim when he became old.[109]

Rabbi Eleazar taught that deceptive speech is like idolatry. Rabbi Eleazar deduced the similarity from the common use of the word "deceiver" to describe Jacob's deception his father in Genesis 27:12, where Jacob says, "I shall seem to him as a deceiver," and to describe idols in Jeremiah 10:15, where idols are described as "the work of deceivers."[110]

But the Gemara cited Jacob as the exemplar of one who, in the words of Psalm 15:3, "has no slander on his tongue," as Jacob's protest to Rebekah in Genesis 27:12, "I shall seem to him as a deceiver," demonstrated that Jacob did not take readily to deception.[111]

Rabbi Joḥanan taught that when Jacob explained his rapid success in obtaining the meat by saying in Genesis 27:20 that it was "because the Lord your God sent me good speed," he was like a raven bringing fire to his nest, courting disaster. For when Jacob said "the Lord your God sent me good speed," Isaac thought to himself that he knew that Esau did not customarily mention the name of God, and if the person before him did so, he must not have been Esau but Jacob. Consequently, Isaac told him in Genesis 27:21, "Come near, I pray, that I may feel you, my son."[112]

Reading Isaac's observation in Genesis 27:27, "See, the smell of my son is as the smell of a field that the Lord has blessed," Rav Judah the son of Rav Samuel bar Shilat said in the name of Rav that Jacob smelled like an apple orchard.[113]

Rabbi Judah ben Pazi interpreted Isaac's blessing of Jacob with dew in Genesis 27:28 merely to pass along to his son what God had deeded to his father Abraham for all time.[114] And Rabbi Ishmael deduced from Isaac's curse of those who cursed Jacob and blessing of those who blessed Jacob in Genesis 27:29 that Jews need not respond to those who curse or bless them, for the Torah has already decreed the response.[115]

Rabbi Judan said that Jacob declared that Isaac blessed him with five blessings, and God correspondingly appeared five times to Jacob and blessed him (Genesis 28:13–15, 31:3, 31:11–13, 35:1, and 35:9–12). And thus, in Genesis 46:1, Jacob "offered sacrifices to the God of his father Isaac," and not to the God of Abraham and Isaac. Rabbi Judan also said that Jacob wanted to thank God for permitting Jacob to see the fulfillment of those blessings. And the blessing that was fulfilled was that of Genesis 27:29, "Let people serve you, and nations bow down to you," which was fulfilled with regard to Joseph. (And thus Jacob mentioned Isaac then on going down to witness Joseph's greatness.)[116]

The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer saw in Isaac's two blessings of Jacob in Genesis 27:28–29 and 28:1–4 an application of the teaching of Ecclesiastes 7:8, "Better is the end of a thing than the beginning." The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer noted that the first blessings with which Isaac blessed Jacob in Genesis 27:28–29 concerned dew and grain—material blessings. The final blessings in Genesis 28:1–4 concerned the foundation of the world, and were without interruption either in this world or in the world to come, for Genesis 28:3 says, "And God Almighty bless you." And Isaac further added the blessing of Abraham, as Genesis 28:4 says, "And may He give you the blessing of Abraham, to you and to your seed with you." Therefore, the Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer concluded that the end of the thing—Isaac's final blessing of Jacob—was better than the beginning thereof.[117]

Interpreting why in Genesis 27:33 "Isaac trembled very exceedingly," Rabbi Joḥanan observed that it was surely unusual for a man who has two sons to tremble when one goes out and the other comes in. Rabbi Joḥanan taught that Isaac trembled because when Esau came in, Gehenna came in with him. Rabbi Aha said that the walls of the house began to seethe from the heat of Gehenna. Hence Genesis 27:33 asks, "who then (אֵפוֹא, eifo)?" for Isaac asked who would be roast (leafot) in Gehenna, him or Jacob?[118]

Rabbi Ḥama bar Ḥaninah interpreted the question "who then?" in Genesis 27:33 to ask who then intervened between Isaac and God that Jacob should receive the blessings. Rabbi Ḥama bar Ḥaninah taught that Isaac thereby hinted at Rebekah's intervention.[119]

The Gemara read Isaac's words in Genesis 27:33, "And I have eaten from everything," to support the Sages' teaching that God gave three people in this world a taste of the World To Come—Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Of Abraham, Genesis 24:1 says, "And the Lord blessed Abraham with everything." And of Jacob, Genesis 33:11 says, "Because I have everything." Thus, already in their lifetimes, they merited everything, perfection. The Gemara read these three verses also to teach that Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob were three people over whom the evil inclination had no sway, as Scripture says about them, respectively, "with everything," "from everything," and "everything," and the completeness of their blessings meant that they did not have to contend with their evil inclinations. And the Gemara read these same three verses to teach that Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob were three of six people over whom the Angel of Death had no sway in their demise—Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Moses, Aaron, and Miriam. As Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob were blessed with everything, the Gemara reasoned, they were certainly spared the anguish of the Angel of Death.[120]

Rabbi Tarfon taught that Isaac's blessing of Esau in Genesis 27:40, "By your sword shall you live," helped to define Edom's character. Rabbi Tarfon taught that God came from Mount Sinai (or others say Mount Seir) and was revealed to the children of Esau, as Deuteronomy 33:2 says, "The Lord came from Sinai, and rose from Seir to them," and "Seir" means the children of Esau, as Genesis 36:8 says, "And Esau dwelt in Mount Seir." God asked them whether they would accept the Torah, and they asked what was written in it. God answered that it included (in Exodus 20:13 and Deuteronomy 5:17), "You shall do no murder." The children of Esau replied that they were unable to abandon the blessing with which Isaac blessed Esau in Genesis 27:40, "By your sword shall you live." From there, God turned and was revealed to the children of Ishmael, as Deuteronomy 33:2 says, "He shined forth from Mount Paran," and "Paran" means the children of Ishmael, as Genesis 21:21 says of Ishmael, "And he dwelt in the wilderness of Paran." God asked them whether they would accept the Torah, and they asked what was written in it. God answered that it included (in Exodus 20:13 and Deuteronomy 5:17), "You shall not steal." The children of Ishamel replied that they were unable to abandon their fathers’ custom, as Joseph said in Genesis 40:15 (referring to the Ishamelites’ transaction reported in Genesis 37:28), "For indeed I was stolen away out of the land of the Hebrews." From there, God sent messengers to all the nations of the world asking them whether they would accept the Torah, and they asked what was written in it. God answered that it included (in Exodus 20:3) and Deuteronomy 5:7), "You shall have no other gods before me." They replied that they had no delight in the Torah, therefore let God give it to God's people, as Psalm 29:11 says, "The Lord will give strength [identified with the Torah] to His people; the Lord will bless His people with peace." From there, God returned and was revealed to the children of Israel, as Deuteronomy 33:2 says, "And he came from the ten thousands of holy ones," and the expression "ten thousands" means the children of Israel, as Numbers 10:36 says, "And when it rested, he said, ‘Return, O Lord, to the ten thousands of the thousands of Israel.’" With God were thousands of chariots and 20,000 angels, and God’s right hand held the Torah, as Deuteronomy 33:2 says, "At his right hand was a fiery law to them."[121]

The Midrash Tehillim told the circumstances in which Esau sought to carry out his desire that Genesis 27:41 reports, "Let the days of mourning for my father be at hand; then will I slay my brother Jacob." The Midrash Tehillim interpreted Psalm 18:41, "You have given me the necks of my enemies," to allude to Judah, because Rabbi Joshua ben Levi reported an oral tradition that Judah slew Esau after the death of Isaac. Esau, Jacob, and all Jacob's children went to bury Isaac, as Genesis 35:29 reports, "Esau, Jacob, and his sons buried him," and they were all in the Cave of Machpelah sitting and weeping. At last Jacob's children stood up, paid their respects to Jacob, and left the cave so that Jacob would not be humbled by weeping exceedingly in their presence. But Esau reentered the cave, thinking that he would kill Jacob, as Genesis 27:41 reports, "And Esau said in his heart: ‘Let the days of mourning for my father be at hand; then will I slay my brother Jacob.’" But Judah saw Esau go back and perceived at once that Esau meant to kill Jacob in the cave. Quickly Judah slipped after him and found Esau about to slay Jacob. So Judah killed Esau from behind. The neck of the enemy was given into Judah’s hands alone, as Jacob blessed Judah in Genesis 49:8 saying, "Your hand shall be on the neck of your enemies." And thus David declared in Psalm 18:41, "You have given me the necks of my enemies," as if to say that this was David's patrimony, since Genesis 49:8 said it of his ancestor Judah.[122]

Reading Genesis 27:41, Rabbi Eleazar contrasted Esau's jealousy with Reuben's magnanimity. As Genesis 25:33 reports, Esau voluntarily sold his birthright, but as Genesis 27:41 says, "Esau hated Jacob," and as Genesis 27:36 says, "And he said, ‘Is not he rightly named Jacob? for he has supplanted me these two times.'" In Reuben's case, Joseph took Reuben's birthright from him against his will, as 1 Chronicles 5:1 reports, "for as much as he defiled his father's couch, his birthright was given to the sons of Joseph." Nonetheless, Reuben was not jealous of Joseph, as Genesis 37:21 reports, "And Reuben heard it, and delivered him out of their hand."[123]

In verse 27:46 where Rebecca expresses her displeasure, the ק is small.

Genesis chapter 28

A Tanna taught in a Baraita that the exalted position of a groom atones for his sins. The Gemara cited Genesis 28:9 as a proof text. The Gemara noted that Genesis 28:9 reports that "Esau went to Ishmael, and took Machalat the daughter of Ishmael, as a wife," but Genesis 36:3 identifies Esau's wife as "Basemat, Ishmael's daughter." The Gemara explained that the name Machalat is cognate with the Hebrew word for forgiveness, mechilah, and thus deduced that Genesis 28:9 teaches that Esau's sins were forgiven upon his marriage.[124]

The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer expanded on the circumstances under which Esau went to be with Ishmael, as reported in Genesis 28:9. Expanding on Genesis 35:27, the Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer told that Jacob took his sons, grandsons, and wives, and went to Kiryat Arba to be near Isaac. Jacob found Esau and his sons and wives there dwelling in Isaac's tents, so Jacob spread his tent apart from Esau's. Isaac rejoiced at seeing Jacob. Rabbi Levi said that in the hour when Isaac was dying, he left his cattle, possessions, and all that he had to his two sons, and therefore they both loved him, and thus Genesis 35:29 reports, "And Esau and Jacob his sons buried him." The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer told that after that, Esau told Jacob to divide Isaac's holdings into two portions, and Esau would choose first between the two portions as a right of being the older. Perceiving that Esau had his eye set on riches, Jacob divided the land of Israel and the Cave of Machpelah in one part and all the rest of Isaac's holdings in the other part. Esau went to consult with Ishmael, as reported in Genesis 28:9. Ishmael told Esau that the Amorite and the Canaanite were in the land, so Esau should take the balance of Isaac's holdings, and Jacob would have nothing. So Esau took Isaac's wealth and gave Jacob the land of Israel and the Cave of Machpelah, and they wrote a perpetual deed between them. Jacob then told Esau to leave the land, and Esau took his wives, children, and all that he had, as Genesis 36:6 reports, "And Esau took his wives . . . and all his possessions which he had gathered in the land of Canaan, and went into a land away from his brother Jacob." As a reward, God gave Esau a hundred provinces from Seir to Magdiel, as Genesis 36:43 reports, and Magdiel is Rome. Then Jacob dwelt safely and in peace in the land of Israel.[125]

Notwithstanding Esau's conflicts with Jacob in Genesis 25–33, a Baraita taught that the descendants of Esau's descendant Haman[126] studied Torah in Benai Berak.[127]

In medieval Jewish interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these medieval Jewish sources:[128]

Genesis chapter 25

Maimonides read the words "And she went to inquire of the Lord" in Genesis 25:22 as an example of a phrase employed by the Torah where a person was not really addressed by the Lord, and did not receive any prophecy, but was informed of a certain thing through a prophet. Maimonides cited the explanation of the Sages that Rebekah went to the college of Eber, and Eber gave her the answer, and this is expressed by the words, "And the Lord said to her" in Genesis 25:23. Maimonides noted that others have explained these words by saying that God spoke to Rebekah through an angel. Maimonides taught that by "angel" Eber is meant, as a prophet is sometimes called an "angel." Alternatively, Maimonides taught that Genesis 25:23 may refer to the angel that appeared to Eber in his vision.[129]

Genesis chapter 27

In the Zohar, Rabbi Simeon saw a reference to Isaac's blessing of Jacob in Isaiah 58:14, "Then shall you delight in the Lord, and I will make you to ride upon the high places of the earth, and I will feed you with the heritage of Jacob your father." Rabbi Simeon interpreted the words of Genesis 27:28, "And God give you of the dew of heaven," to mean "the heritage of Jacob" in Isaiah 58:14. Rabbi Simeon taught that with these words, Isaac indicated that Jacob's children would rise again from the dead at the time to come, by means of heavenly dew that shall issue forth from God. Rabbi Abba responded to Rabbi Simeon that there was more significance to Isaac's blessing than he had thought.[130]

Nachmanides taught that from the moment that Isaac blessed Jacob, Isaac knew from Divine inspiration that his blessing rested on Jacob. This was then the reason for his violent trembling, for he knew that his beloved son Esau had lost the blessing forever. After he said (in Genesis 27:33) "Who then is he who came," Isaac realized that Jacob had been the one who came before him to receive the blessing.[131]

Notwithstanding Esau's conflicts with Jacob in Genesis 25–33, the Baal HaTurim, reading the Priestly Blessing of Numbers 6:24–26, noted that the numerical value (gematria) of the Hebrew word for "peace" (שָׁלוֹם, shalom) equals the numerical value of the word "Esau" (עֵשָׂו, Eisav). The Baal HaTurim concluded that this hints at the Mishnaic dictum (in Avot 4:15[132]) that one should always reach out to be the first to greet any person, even an adversary.[133]

In modern interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these modern sources:

Genesis chapters 25–33

Hermann Gunkel wrote that the legend cycle of Jacob-Esau-Laban divided clearly into the legends (1) of Jacob and Esau (Genesis 25:19–34; 27:1–45; 27:46–28:9; 32:3–21; 33:1–17), (2) of Jacob and Laban (Genesis 29:1–30; 30:25–31:55), (3) of the origin of the twelve tribes (Genesis 29:31–30:24), and (4) of the origin of ritual observances (Genesis 28:10–22; 32:1–2, 22–32).[134]

Walter Brueggemann suggested a chiastic structure to the Jacob narrative (shown in the chart below), moving from conflict with Esau to reconciliation with Esau. Within that is conflict with Laban moving to covenant with Laban. And within that, at the center, is the narrative of births, in which the birth of Joseph (at Genesis 30:24) marks the turning point in the entire narrative, after which Jacob looks toward the Land of Israel and his brother Esau. In the midst of the conflicts are the two major encounters with God, which occur at crucial times in the sequence of conflicts.[135]

| Conflict with Esau | Reconciliation with Esau | |||||

| 25:19–34; 27:1–45; 27:46–28:9 | 32–33:17 | |||||

| Meeting at Bethel | Meeting at Penu'el | |||||

| 28:10–22 | 32–33:17 | |||||

| Conflict with Laban | Covenant with Laban | |||||

| 29:1–30 | 30:25–31:55 | |||||

| Births | ||||||

| 29:31–30:24 |

Acknowledging that some interpreters view Jacob's two encounters with God in Genesis 28:10–22 and 32–33:17 as parallel, Terence Fretheim argued that one may see more significant levels of correspondence between the two Bethel stories in Genesis 28:10–22 and 35:1–15, and one may view the oracle to Rebekah in Genesis 29:23 regarding "struggling" as parallel to Jacob's struggle at the Jabbok in Genesis 32–33:17. Fretheim concluded that these four instances of Divine speaking link to each other in complex ways.[136]

Genesis chapter 25

James Kugel wrote that Gunkel's concept of the etiological tale led 20th century scholars to understand the stories of the rivalry of Jacob and Esau in Genesis 25:19–26, Genesis 25:29–34, and Genesis 27 to explain something about the national character (or national stereotype) of Israel and Edom at the time of the stories’ composition, a kind of projection of later reality back to the "time of the founders." In this etiological reading, that Esau and Jacob were twins explained the close connection between Edom and Israel, their similar dialects, and cultural and kinship ties, while the competition between Esau and Jacob explained the off-and-on enmity between Edom and Israel in the Biblical period. Kugel reported that some biblical scholars saw an analogue in Israelite history: Esau's descendants, the Edomites, had been a sovereign nation while the future Israel was still in formation (see Genesis 36:31), making Edom the "older brother" of Israel. But then, in the 10th century BCE, David unified Israel and conquered Edom (see 2 Samuel 8:13–14; 1 Kings 11:15–16; and 1 Chronicles 18:12–13), and that is why the oracle Genesis 25:23 gave Rebekah during her pregnancy said that "the older will end up serving the younger." Kugel reported that scholars thus view the stories of the young Jacob and Esau as created to reflect a political reality that came about in the time of David, indicating that these narratives were first composed in the early 10th century BCE, before the Edomites succeeded in throwing off their Israelite overlords, at that time when Israel might feel "like a little kid who had ended up with a prize that was not legitimately his." When Edom regained its independence, the stolen blessing story underwent a change (or perhaps was created out of whole cloth to reflect Edom's resurgence). For while Israel still dominated Edom, the story ought to have ended with Isaac's blessing of Jacob in Genesis 27:28. But Isaac's blessing of Esau in Genesis 27:40, "By your sword you will live, and you will indeed serve your brother; but then it will happen that you will break loose and throw his yoke from off your neck," reflects a reformulation (or perhaps new creation) of the story in the light of the new reality that developed half a century later.[137]

Gary Rendsburg read in Genesis 25:19–29—which personifies Edom, a Transjordanian state ruled by David and Solomon, as the brother of Jacob/Israel—to indicate that the author of Genesis sought to portray the ancestor of this country as related to the patriarchs in order to justify Israelite rule over Edom. Rendsburg noted that during the United Monarchy, Israel governed most firmly the nations geographically closest to Israel. 2 Samuel reports that while Israel permitted the native kings of Moab and Ammon to rule as tributary vassals, Israel deposed the king of Edom, and David and Solomon exercised direct rule over their southeastern neighbor. Rendsburg deduced that this explains why Edom, in the character of Esau, is seen as a twin brother of Israel, in the character of Jacob, while Moab and Ammon, as portrayed in Genesis 19:30–38 by Lot's two sons, were more distantly related. Rendsburg also noted that in Genesis 27:40, Isaac predicted that Esau would throw off the yoke of Jacob, reflecting the Edomite rebellion against Israel during Solomon's reign reported in 1 Kings 11:14–22. Rendsburg concluded that royal scribes living in Jerusalem during the reigns of David and Solomon in the tenth century BCE were responsible for Genesis; their ultimate goal was to justify the monarchy in general, and the kingship of David and Solomon in particular; and Genesis thus appears as a piece of political propaganda.[138]

Rendsburg noted that Genesis often repeats the motif of the younger son. God favored Abel over Cain in Genesis 4; Isaac superseded Ishmael in Genesis 16–21; Jacob superseded Esau in Genesis 25–27; Judah (fourth among Jacob's sons, last of the original set born to Leah) and Joseph (eleventh in line) superseded their older brothers in Genesis 37–50; Perez superseded Zerah in Genesis 38 and Ruth 4; and Ephraim superseded Manasseh in Genesis 48. Rendsburg explained Genesis's interest with this motif by recalling that David was the youngest of Jesse’s seven sons (see 1 Samuel 16), and Solomon was among the youngest, if not the youngest, of David’s sons (see 2 Samuel 5:13–16). The issue of who among David’s many sons would succeed him dominates the Succession Narrative in 2 Samuel 13 through 1 Kings 2. Amnon was the firstborn, but was killed by his brother Absalom (David’s third son) in 2 Samuel 13:29. After Absalom rebelled, David’s general Joab killed him in 2 Samuel 18:14–15. The two remaining candidates were Adonijah (David’s fourth son) and Solomon, and although Adonijah was older (and once claimed the throne when David was old and feeble in 1 Kings 1), Solomon won out. Rendsburg argued that even though firstborn royal succession was the norm in the ancient Near East, the authors of Genesis justified Solomonic rule by imbedding the notion of ultimogeniture into Genesis’s national epic. An Israelite could thus not criticize David’s selection of Solomon to succeed him as king over Israel, because Genesis reported that God had favored younger sons since Abel and blessed younger sons of Israel—Isaac, Jacob, Judah, Joseph, Perez, and Ephraim—since the inception of the covenant.[139]

Reading the words of Genesis 25:22, "why do I live," Robert Alter wrote that Rebekah's "cry of perplexity and anguish" over her difficult pregnancy was "terse to the point of being elliptical." Alter suggested that Rebekah's words might even be construed as a broken-off sentence—"Then why am I . . . ?"[140]

Fretheim observed an ambiguity in the language of Genesis 25:23: The brother who would be stronger was not necessarily the brother who would be served. Fretheim wrote that Genesis 25:23 predicted either that the older (Esau) would be the weaker of the two and would serve the younger (Jacob), or, more likely, that the older would be the stronger and would serve the younger.[141]

And Richard Elliott Friedman noted that readers usually take Genesis 25:23 to convey that God told Rebekah that her younger son, Jacob, would dominate her older son, Esau. Thus, some have argued that Rebekah did not manipulate the succession when she sent Jacob to pose as Esau, but simply fulfilled God's will. But Friedman called this reading of Genesis 25:23 a misunderstanding of the "subtle, exquisitely ambiguous" wording of the verse. Friedman wrote that in Biblical Hebrew, the subject may either precede or follow the verb, and the object may either precede or follow the verb. Thus, Friedman argued that it is sometimes impossible to tell which word is the subject and which is the object, especially in poetry. Friedman argued that this is the case in Genesis 25:23, which he argued can mean either, "the elder will serve the younger," or, "the elder, the younger will serve." Friedman concluded that "like the Delphic oracles in Greece, this prediction contains two opposite meanings, and thus the person who receives it—Rebekah—can hear whatever she wants (consciously or subconsciously) to hear."[142]

Ephraim Speiser wrote that originally the name Jacob, rather than as explained in Genesis 25:26, was likely from Y‘qb-'l, and meant something like "may God protect."[143]

Reading the characterization of Jacob as "a simple man" (אִישׁ תָּם, ish tam) in Genesis 25:27, Alter suggested that the Hebrew adjective "simple" (תָּם, tam) suggests integrity or even innocence. Alter pointed out that in Biblical idiom, as in Jeremiah 17:9, the heart can be "crooked" (עָקֹב, ‘akov), the same root as Jacob's name, and the idiomatic antonym is "pureness" or "innocence"—תָּם, tam—of heart, as in Genesis 20:5. Alter concluded that there may well be a complicating irony in the use of this epithet for Jacob in Genesis 25:27, as Jacob's behavior is far from simple or innocent as Jacob bargains for Esau's birthright in the very next scene.[144]

Reading Genesis 25:29, "Jacob cooked food," Ohr ha-Chaim suggested that Jacob did so because he saw how effective Esau's providing Isaac with delicious meals had been in cementing Isaac's love for Esau, and thus Jacob tried to emulate Esau's success.[145]

Genesis chapter 26

In Genesis 26:4, God reminded Isaac that God had promised Abraham that God would make his heirs as numerous as the stars. In Genesis 15:5, God promised that Abraham's descendants would be as numerous as the stars of heaven. In Genesis 22:17, God promised that the Abraham's descendants would be as numerous as the stars of heaven and the sands on the seashore. Carl Sagan reported that there are more stars in the universe than sands on all the beaches on the Earth.[146]

Baruch Spinoza read the report of Genesis 26:5 that Abraham observed the worship, precepts, statutes, and laws of God to mean that Abraham observed the worship, statutes, precepts, and laws of king Melchizedek. Spinoza read Genesis 14:18–20 to relate that Melchizedek was king of Jerusalem and priest of the Most High God, that in the exercise of his priestly functions (like those Numbers 6:23 describes) he blessed Abraham, and that Abraham gave to this priest of God a tithe of all his spoils. Spinoza deduced from this that before God founded the Israelite nation, God constituted kings and priests in Jerusalem, and ordained for them rites and laws. Spinoza deduced that while Abraham sojourned in the city, he lived scrupulously according to these laws, for Abraham had received no special rites from God.[147]

Reading the three instances of the wife-sister motif in (a) Genesis 12:10–20; (b) Genesis 20:1–18; and (c) Genesis 26:6–11, Speiser argued that in a work by a single author, these three cases would present serious contradictions: Abraham would have learned nothing from his narrow escape in Egypt, and so tried the same ruse in Gerar; and Abimelech would have been so little sobered by his perilous experience with Abraham and Sarah that he fell into the identical trap with Isaac and Rebekah. Speiser concluded (on independent grounds) that the Jahwist was responsible for incidents (a) and (c), while the Elohist was responsible for incident (b). If the Elohist had been merely an annotator of the Jahwist, however, the Elohist would still have seen the contradictions for Abimelech, a man of whom the Elohist clearly approved. Speiser concluded that the Jahwist and the Elohist therefore must have worked independently.[148]

Genesis chapter 27

Speiser read the details of Jacob's behavior in Genesis 27:1–40 to show that, although the outcome favored Jacob, the Jahwist's personal sympathies lay with Isaac and Esau, the victims of the ruse.[149] Speiser read the unintended blessing of Jacob by Isaac in Genesis 27 to teach that no one may grasp God's complete design, which remains reasonable and just no matter who the chosen agent may be at any given point.[150]

Gunther Plaut argued that Isaac was not really deceived. Reading the story with close attention to the personality of Isaac, Plaut concluded that throughout the episode, Isaac was subconsciously aware of Jacob's identity, but, as he was unable to admit this knowledge, he pretended to be deceived. Plaut thus saw a plot within a plot, as Rebekah and Jacob laid elaborate plans for deceiving Isaac, while unknown to them Isaac looked for a way to deceive himself, in order to carry out God's design to bless his less-loved son. Plaut argued that Isaac was old but not senile. In his heart, Isaac had long known that Esau could not carry on the burden of Abraham and that, instead, he had to choose his quiet and complicated younger son Jacob. In Plaut's reading, weak and indecisive man and father that Isaac was, he did not have the courage to face Esau with the truth. His own blindness and Rebekah's ruse came literally as a godsend. Plaut noted that Isaac did not reprimand Jacob. Plaut concluded that no one, not even Esau, was deceived, for even Esau knew that Jacob was the chosen one.[151]

Noting that the name Jacob can mean "he will deceive" and that in Genesis 27:35, Jacob's father Isaac accused Jacob of acting "deceitfully" (בְּמִרְמָה, bemirmah), a word that derives from the same root as the adjective "crafty" (עָרוּם, arum) applied to the serpent in Genesis 3:1, Karen Armstrong argued that Jacob's example makes clear that God does not choose one person over another because of the person's moral virtue.[152]

Commandments

According to Maimonides and Sefer ha-Chinuch, there are no commandments in the parashah.[153]

In the liturgy

In the Blessing after Meals (Birkat Hamazon), at the close of the fourth blessing (of thanks for God's goodness), Jews allude to God's blessing of the Patriarchs described in Genesis 24:1, 27:33, and 33:11.[154]

The Weekly Maqam

In the Weekly Maqam, Sephardi Jews each week base the songs of the services on the content of that week's parashah. For Parashat Toledot, Sephardi Jews apply Maqam Mahour, the maqam that portrays emotional instability and anger. This maqam is similar to Maqam Rast in tone. It is appropriate, because in this parashah, Esau portrays these character traits as he loses out on the major blessings.[155]

Haftarah

A haftarah is a text selected from the books of Nevi'im ("The Prophets") that is read publicly in the synagogue after the reading of the Torah on Sabbath and holiday mornings. The haftarah usually has a thematic link to the Torah reading that precedes it.

The specific text read following Parashat Toledot varies according to different traditions within Judaism. Examples are:

- for Ashkenazi Jews and Sephardi Jews: Malachi 1:1–2:7

- for Karaite Jews: Isaiah 65:23–66:18

Connection to the parshah

Malachi 1 opens with God noting "I loved Jacob, and I hated Esau," before promising retribution on Esau's descendants, the people of Edom.

Notes

- "Bereshit Torah Stats". Akhlah Inc. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- "Parashat Toldot". Hebcal. Retrieved November 13, 2014.

- See, e.g., Menachem Davis, editor, The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Bereishis/Genesis (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2006), pages 135–56.

- Genesis 25:20–21.

- Genesis 25:22–23.

- Genesis 25:24–26.

- Genesis 25:26.

- Genesis 25:27.

- Genesis 25:28.

- Genesis 25:29–30.

- Genesis 25:31–34.

- See, e.g., Menachem Davis, editor, Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Bereishis/Genesis, page 139.

- Genesis 26:1.

- Genesis 26:2–5.

- See, e.g., Menachem Davis, editor, Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Bereishis/Genesis, page 140.

- Genesis 26:6–7.

- Genesis 26:8–9.

- Genesis 26:9.

- Genesis 26:10–11.

- Genesis 26:12.

- See, e.g., Menachem Davis, editor, Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Bereishis/Genesis, page 141.

- Genesis 26:13–14.

- Genesis 26:15–16.

- Genesis 26:17–18.

- Genesis 26:19–21.

- Genesis 26:22.

- See, e.g., Menachem Davis, editor, Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Bereishis/Genesis, page 143.

- Genesis 26:23–24.

- Genesis 26:25.

- Genesis 26:26–27.

- Genesis 26:28–29.

- See, e.g., Menachem Davis, editor, Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Bereishis/Genesis, page 144.

- Genesis 26:30–31.

- Genesis 26:32–33.

- See, e.g., Menachem Davis, editor, Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Bereishis/Genesis, page 145.

- Genesis 26:34–35.

- Genesis 27:1–4.

- Genesis 27:5–10.

- Genesis 27:11–12.

- Genesis 27:13.

- Genesis 27:14–17.

- Genesis 27:18–19.

- Genesis 27:20.

- Genesis 27:21.

- Genesis 27:22.

- Genesis 27:24–25.

- Genesis 27:26–27.

- See, e.g., Menachem Davis, editor, Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Bereishis/Genesis, page 150.

- Genesis 27:27–29.

- Genesis 27:30–31.

- Genesis 27:32.

- Genesis 27:33.

- Genesis 27:34–35.

- Genesis 27:36.

- Genesis 27:37.

- Genesis 27:38–40.

- Genesis 27:41.

- Genesis 27:42–45.

- Genesis 27:46–28:2.

- Genesis 28:3–4.

- See, e.g., Menachem Davis, editor, Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Bereishis/Genesis, page 155.

- Genesis 28:5–9.

- See, e.g., Menachem Davis, editor, Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Bereishis/Genesis, pages 155–56.

- See, e.g., Richard Eisenberg, "A Complete Triennial Cycle for Reading the Torah," in Proceedings of the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Conservative Movement: 1986–1990 (New York: The Rabbinical Assembly, 2001), pages 383–418.

- For more on inner-Biblical interpretation, see, e.g., Benjamin D. Sommer. "Inner-biblical Interpretation." In The Jewish Study Bible: Second Edition. Edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, pages 1835–41. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Hosea 12:3–5.

- Numbers 12:7 and 12:8; Joshua 1:2 and 1:7; 2 Kings 21:8 and Malachi 3:22.

- Numbers 14:24.

- 2 Samuel 3:18; 7:5; and 7:8; 1 Kings 11:13; 11:32; 11:34; 11:36; 11:38; and 14:8; 2 Kings 19:34 and 20:6; Isaiah 37:35; Jeremiah 33:21; 33:22; and 33:26; Ezekiel 34:23; 34:24; and 37:24; Psalm 89:3 and 89:20; and 1 Chronicles 17:4 and 17:7.

- Isaiah 20:3.

- Isaiah 22:20.

- Isaiah 41:8; 41:9; 42:1; 42:19; 43:10; 44:1; 44:2; 44:21; 49:3; 49:6; and 52:13; and Jeremiah 30:10; 46:27; and 46:27; and Ezekiel 28:25 and 37:25.

- Jeremiah 25:9; 27:6; and 43:10.

- Haggai 2:23.

- Zechariah 3:8.

- Job 1:8; 2:3; 42:7; and 42:8.

- For more on classical rabbinic interpretation, see, e.g., Yaakov Elman. "Classical Rabbinic Interpretation." In The Jewish Study Bible: Second Edition. Edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, pages 1859–78.

- Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer, chapter 32.

- Babylonian Talmud Yevamot 64a.

- Babylonian Talmud Sukkah 14a (Rabbi Eleazar); Babylonian Talmud Yevamot 64a (Rabbi Isaac); Genesis Rabbah 63:5 (Resh Lakish).

- Genesis Rabbah 63:5.

- Pesikta de-Rav Kahana, piska 20, paragraph 1.

- Genesis Rabbah 60:13.

- Genesis Rabbah 63:6.

- Midrash Tadshe 21, in Menahem M. Kasher. Torah Sheleimah, 25, 95–96. Jerusalem, 1927, in Encyclopedia of Biblical Interpretation. Translated by Hyman Klein, volume 4, page 6. New York: American Biblical Encyclopedia Society, 1959.

- Jerusalem Talmud Sotah 31b (7:1).

- Genesis Rabbah 67:9.

- Babylonian Talmud Megillah 6a.

- Genesis Rabbah 63:10.

- Deuteronomy Rabbah 1:17.

- Genesis Rabbah 94:5.

- Babylonian Talmud Bava Batra 16b.

- Genesis Rabbah 63:1.

- Mishnah Kiddushin 4:14; Tosefta Kiddushin 5:21; Babylonian Talmud Kiddushin 82a.

- Tosefta Sotah 10:5.

- Tosefta Sotah 10:6.

- Genesis Rabbah 64:3.

- Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer, chapter 48.

- Genesis Rabbah 64:6; see also Babylonian Talmud Taanit 8b.

- Tosefta Berakhot 6:8.

- Genesis Rabbah 64:9.

- Sifre to Deuteronomy 2:3.

- Genesis Rabbah 64:10.

- Saadiah ben David Tha'azi of Yemen. Midrash Habiur. Second half of the 14th century, in Menahem M. Kasher. Torah Sheleimah, 26, 110–11. Jerusalem, 1927, in Encyclopedia of Biblical Interpretation. Translated by Harry Freedman, volume 4, page 34. New York: American Biblical Encyclopedia Society, 1965.

- Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer, chapter 36.

- Genesis Rabbah 65:1.

- Babylonian Talmud Yoma 28b.

- Babylonian Talmud Megillah 28a; see also Babylonian Talmud Bava Kamma 93a.

- Genesis Rabbah 65:10.

- Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 92a.

- Babylonian Talmud Makkot 24a.

- Genesis Rabbah 65:19.

- Babylonian Talmud Taanit 29b.

- Jerusalem Talmud Berakhot 55b.

- Jerusalem Talmud Berakhot 85b.

- Genesis Rabbah 94:5.

- Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer, chapter 35.

- Genesis Rabbah 67:2.

- Genesis Rabbah 67:2.

- Babylonian Talmud Bava Batra 16b–17a.

- Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer, chapter 41.

- Midrash Tehillim 18:32.

- Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 7b.

- Jerusalem Talmud Bikkurim 23b.

- Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer, chapter 38.

- Genesis 36:12 identifies Amalek as Esau’s grandson. Numbers 24:7 identifies the Amalekites with the Agagites. Esther 3:1 identifies Haman as an Agagite.

- Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 96b.

- For more on medieval Jewish interpretation, see, e.g., Barry D. Walfish. "Medieval Jewish Interpretation." In The Jewish Study Bible: Second Edition. Edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, pages 1891–915.

- Maimonides. The Guide for the Perplexed, part 2, chapter 41. Cairo, Egypt, 1190, in, e.g., Moses Maimonides. The Guide for the Perplexed. Translated by Michael Friedländer, page 236. New York: Dover Publications, 1956.

- Zohar, Shemot, section 2, page 83a. Spain, late 13th century, in, e.g., The Zohar: Pritzker Edition. Translation and commentary by Daniel C. Matt, volume 4, pages 459–60. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007.

- Nachmanides. Commentary on the Torah. Jerusalem, circa 1270, in, e.g., Ramban (Nachmanides): Commentary on the Torah. Translated by Charles B. Chavel, page 343. New York: Shilo Publishing House, 1971.

- Avot 4:15, in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, page 683.

- Jacob ben Asher (The Baal Ha-Turim). Rimze Ba'al ha-Turim. Early 14th century, in, e.g., Baal Haturim Chumash: Bamidbar/Numbers. Translated by Eliyahu Touger; edited and annotated by Avie Gold, volume 4, page 1419. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2003.

- Hermann Gunkel. Genesis: Translated and Explained. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1901. Introduction reprinted as The Legends of Genesis: The Biblical Saga and History. Translated by William H. Carruth. 1901. Reprinted, e.g., with an introduction by William F. Albright, page 45. New York: Schocken Books 1964; Reissue edition, 1987. See also Walter Brueggemann. Genesis: Interpretation: A Bible Commentary for Teaching and Preaching, page 205. Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1982. (identifying verses of these legends).

- Walter Brueggemann. Genesis: Interpretation: A Bible Commentary for Teaching and Preaching, pages 211–13. See also Gary A. Rendsburg. The Great Courses: The Book of Genesis: Part 2, page 13. Chantilly, Virginia: The Teaching Company, 2006. (similar chiastic structure).

- Terence E. Fretheim. "The Book of Genesis." In The New Interpreter's Bible. Edited by Leander E. Keck, volume 1, page 519. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1994.

- James L. Kugel. How To Read the Bible: A Guide to Scripture, Then and Now, pages 143–46. New York: Free Press, 2007.

- Gary A. Rendsburg, "Reading David in Genesis: How we know the Torah was written in the tenth century B.C.E." Bible Review, volume 17, number 1 (February 2001): pages 20, 23, 26–27.

- Gary A. Rendsburg, "Reading David in Genesis: How we know the Torah was written in the tenth century B.C.E." Bible Review, volume 17, number 1 (February 2001): pages 20, 28–30.

- Robert Alter. The Five Books of Moses: A Translation with Commentary, page 129. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2004.

- Terence E. Fretheim. "The Book of Genesis." In The New Interpreter's Bible. Edited by Leander E. Keck, volume 1, page 521.

- Richard Elliott Friedman. Commentary on the Torah: With a New English Translation, page 88. New York: Harper San Francisco, 2001. See also Robert Alter. The Five Books of Moses: A Translation with Commentary, page 129.

- Ephraim A. Speiser. Genesis: Introduction, Translation, and Notes, page 197. New York: Anchor Bible, 1964. See also W. Gunther Plaut. The Torah: A Modern Commentary, page 173. New York: Union of American Hebrew Congregations, 1981. ("May El protect"). Victor P. Hamilton. The Book of Genesis: Chapters 18–50, page 178–79. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1995. ("May El protect (him)" or "El will protect (him)"). Robert Alter. The Five Books of Moses: A Translation with Commentary, page 130. ("God protects" or "God follows after").

- Robert Alter. The Five Books of Moses: A Translation with Commentary, page 130.

- Chaim ibn Attar. Ohr ha-Chaim. Venice, 1742, in Chayim Ben Attar. Or Hachayim: Commentary on the Torah. Translated by Eliyahu Munk, page 206. Brooklyn, New York: Lambda Publishers, 1999.

- Carl Sagan. “Journeys in Space and Time.” Cosmos: A Personal Voyage, episode 8. Cosmos Studios, 1980.

- Baruch Spinoza. Theologico-Political Treatise, chapter 3. Amsterdam, 1670, in, e.g., Baruch Spinoza. Theological-Political Treatise. Translated by Samuel Shirley, page 39. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, second edition, 2001.

- Ephraim A. Speiser. Genesis: Introduction, Translation, and Notes, volume 1, pages xxxi–xxxii.

- Ephraim A. Speiser. Genesis: Introduction, Translation, and Notes, volume 1, page xxvii.

- Ephraim A. Speiser. Genesis: Introduction, Translation, and Notes, volume 1, page xxviii.

- W. Gunther Plaut. The Torah: A Modern Commentary, pages 190–91.

- Karen Armstrong, In the Beginning: A New Interpretation of Genesis (New York: Knopf, 1996), page 75.

- Maimonides. Mishneh Torah. Cairo, Egypt, 1170–1180, in Maimonides. The Commandments: Sefer Ha-Mitzvoth of Maimonides. Translated by Charles B. Chavel, 2 volumes. London: Soncino Press, 1967. Sefer HaHinnuch: The Book of [Mitzvah] Education. Translated by Charles Wengrov, volume 1, page 87. 1991.

- Menachem Davis, editor, The Schottenstein Edition Siddur for the Sabbath and Festivals with an Interlinear Translation (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2002), page 172; Reuven Hammer. Or Hadash: A Commentary on Siddur Sim Shalom for Shabbat and Festivals, page 342. New York: The Rabbinical Assembly, 2003.

- See Mark L. Kligman. "The Bible, Prayer, and Maqam: Extra-Musical Associations of Syrian Jews." Ethnomusicology, volume 45 (number 3) (Autumn 2001): pages 443–479. Mark L. Kligman. Maqam and Liturgy: Ritual, Music, and Aesthetics of Syrian Jews in Brooklyn. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2009.

Further reading

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these sources:

Biblical

- Genesis 15:5 (numerous as stars); 22:17 (numerous as stars).

- Deuteronomy 1:10 (numerous as stars); 17:16 (not to go to Egypt).

- Joshua 24:4.

- Jeremiah 42:13-22 (not to go to Egypt).

- Malachi 1:2–3.

Early nonrabbinic