Gentile Portino da Montefiore

Gentile Portino da Montefiore (also Gentile Partino di Montefiore, Latin: Gentilis de Monteflorum; c. 1240 – 27 October 1312) was an Italian Franciscan friar and prelate, who was created Cardinal-Priest of Santi Silvestro e Martino ai Monti by Pope Boniface VIII in 1300. He served as Major Penitentiary of the Roman Curia from 1302 to 1305. Pope Clement V sent him to Hungary as a papal legate in 1308, with the primary task of assuring the Angevins the Hungarian throne. Gentile built the San Martino Chapel in the Lower Basilica of Saint Francis of Assisi, dedicated to Saint Martin of Tours. He was buried in the neighboring Chapel of St. Louis.

Gentile Portino da Montefiore | |

|---|---|

| Cardinal-Priest of Santi Silvestro e Martino ai Monti | |

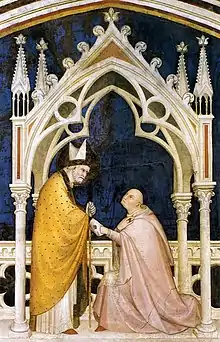

Dedication by cardinal Gentile Portino da Montefiore, as depicted one of the frescoes by Simone Martini in San Martino Chapel | |

| Other post(s) | Major Penitentiary |

| Orders | |

| Created cardinal | 2 March 1300 by Pope Boniface VIII |

| Rank | Cardinal-Priest |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 1240 |

| Died | 27 October 1312 Lucca, Republic of Lucca |

| Buried | Chapel of St. Louis, Basilica of Saint Francis of Assisi |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic |

| Alma mater | University of Paris |

Ecclesiastical career

Gentile was born around 1240 into a wealthy noble family in Montefiore dell'Aso.[1] He was still a child, when entered the Order of Friars Minor in 1248. He graduated in theology from the University of Paris (Sorbonne) and obtained the title of magister by 1294.[2] He returned to Italy around that year. He met and became a friend of Cardinal Benedetto Caetani in Perugia. Caetani was elected as Pope Boniface VIII shortly thereafter. Gentile was made lector at the Roman Curia in 1296.[2]

Gentile was created Cardinal-Priest of Santi Silvestro e Martino ai Monti by Pope Boniface on 2 March 1300.[2] Other sources say, his creation occurred already in 1298.[3] Together with Cardinal Niccolò Boccasini (the future Pope Benedict XI), Gentile was charged by Boniface to solve the problem of the distance that needed to exist between the monastic orders of the Franciscans and the Dominicans. They jointly proposed the draft on 28 July 1300, which was then ratified by Niccolò Boccasini as Pope Benedict XI in December 1303.[2] Gentile was appointed Major Penitentiary at the Roman Curia in 1302, holding the office until 1305.[1] He was present in Anagni on 7 September 1303, when an army led by Philip IV of France's minister Guillaume de Nogaret and Sciarra Colonna attacked Boniface and his escort at his palace. He continued his work in Rome after the death of Boniface. He participated in the 1303 and 1304–1305 papal conclaves. Pope Clement V entrusted him with the cure and the administration of the Basilica of Saint Praxedes in 1305.[2] He also performed diplomatic missions on behalf of the pope, for instance he was sent to Paris in 1305.[3] He resided in the papal court in Lyon at the end of June 1307, when he reviewed several elections of bishops and abbots.[2]

Papal legate in Hungary

Charles' mainstay

Pope Clement V appointed Gentile as papal legate with full authority and sent him to the Kingdom of Hungary in Poitiers on 8 August 1307.[4] His legation was also mandated to Poland, Dalmatia, Croatia, Bosnia (Rama), Serbia, Galicia–Volhynia and Cumania.[5] After the death of Andrew III of Hungary and the extinction of the Árpád dynasty in 1301, a civil war between various claimants to the throne – Charles of Anjou, Wenceslaus of Bohemia, and Otto of Bavaria – broke out. Pope Boniface's first legate, Niccolò Boccasini convinced the majority of the Hungarian prelates to accept Charles's reign, but unsuccessfully tried to acknowledge the Anjous' claim with the powerful barons of the realm. Pope Boniface who regarded Hungary as a fief of the Holy See declared Charles the lawful king of Hungary on 31 May 1303. Charles defeated his enemies by the summer of 1307 (Wenceslaus left Hungary, while Otto was imprisoned), but the so-called oligarchs still governed their province de facto independently of the royal power. Pope Clement sent his representative, Gentile in this situation.[6] Gentile was mandated to ensure Charles' reign, to restore shattered church discipline, to recover of lost and unlawfully usurped church property and to ensure the filling of church positions in accordance with the canon law. Gentile also received permission to the use of church punishment, if necessary.[7][8] Gentile left the papal court on 17 October 1307. He met Charles II and Mary – Charles' grandparents – in Naples.[9] Charles II gave instructions to prepare two ships for the papal legate in March 1308.[10] Gentile then moved forward to Bologna.[9]

Gentile arrived with the two ships to Split (Spalato) in Croatia in union with Hungary at the end of May 1308.[11] He spent the following months in various Adriatic coastal cities, Trogir (Trau), Skradin (Scardona), Zadar (Zara) and Senj (Segna), where dealt with church affairs of the Dalmatian dioceses.[12] For instance, he launched an investigation against the pro-Venetian Giorgio Ermolao, the Bishop of Arbe and his partisans, who did not recognize Gentile's jurisdiction over Dalmatia.[5] He also refused the election of Lampert as Bishop of Hvar. He also entrusted the Chapter of Split to elect a new archbishop.[13] Gentile provided 40-day indulgences to four Dalmatian churches during these months.[14] He was greeted by Charles I and Archbishop Thomas of Esztergom in Zagreb around early September. The companion, through Csetény, arrived to Buda in October and Gentile was accommodated in the Dominican St. Nicholas monastery within the castle.[12]

Gentile managed to persuade the most powerful oligarch Matthew Csák to accept King Charles' rule at their meeting in the Pauline Monastery of Kékes on 10 November 1308. On his side, Hungarian prelates Thomas of Esztergom and John of Nyitra also attended the event, as well as the provincial heads of the Dominicans and Minorites in Hungary. It is presumable that Matthew Csák also promised that he will provide assistance to Charles in his unification war against the rebellious oligarchs. In exchange, Matthew Csák was offered to become Master of the treasury, then the most influential dignity in the royal court, and he was guaranteed to keep half of the recovered royal estates during the campaign.[15] In the next few weeks, Gentile persuaded the most powerful lords one by one to accept Charles's rule. At the Diet, which was held in the Dominican monastery in Pest and chaired by Gentile, Charles was unanimously proclaimed king on 27 November 1308.[16][17] In his speech, the legate referred to the Gospel of Matthew 13,27 ("Sir, didn’t you sow good seed in your field?") and explained the Father Almighty was the one, who spread seed into the soil of Hungary, from which "numerous excellent, holy and pure kings had sprouted". Among them, Saint Stephen, the first one, gained the crown "consecrated by the high priest of Rome", he claimed. The last sentence caused rumbling and indignation in the ranks of the audience. Some protesters feared the freedom of the country from the Holy See. Nevertheless, they accepted Charles as their king.[18]

The papal legate convoked the synod of the Hungarian prelates, who declared the monarch inviolable in December 1308. There, they also urged Ladislaus Kán, who had captured Otto, to hand over the Holy Crown to Charles. However, the Transylvanian oligarch refused to do so. During the synod, Gentile also dealt with ecclesiastical affairs. The prelates also threatened with excommunication of those noblemen, who unlawfully seized and usurped church property. In preparation for Charles' second coronation, Henry Kőszegi met papal legate Gentile and other prelates in his manor on 4 June 1309, where he confirmed his oath of allegiance to Charles on behalf of himself and his family.[19] Having waited in vain a half years that Ladislaus Kán changes his mind, Gentile consecrated a new crown for Charles. Simultaneously, the Transylvanian oligarch also entered an alliance with Stefan Dragutin, also a descendant of the Árpáds, which urged the cardinal to secure Charles' legitimacy.[20] Archbishop Thomas crowned Charles king with the new crown in the Church of Our Lady in Buda on 15 or 16 June 1309. However, most Hungarians regarded his second coronation invalid.[16] Gentile left Buda for Pressburg (present-day Bratislava, Slovakia) in the autumn of 1309. Gentile attempted to marry Charles' sister Clementia off to a Hungarian lord, but the princess was engaged to Ferdinand of Majorca before that.[21] After the negotiations with Ladislaus Kán did not proceed, the papal legate excommunicated the lord and placed his province under interdict on 25 December 1309. Gentile, who sent Benedict, Bishop-elect of Transylvania to meet the oligarch, was still trusted in the deal and promised if Ladislaus Kán returns the crown on the deadline of 2 February 1310, he withdraws the penalty imposed.[22] Thereafter Thomas, alongside Amadeus Aba and Dominic Rátót, negotiated with the voivode in Szeged on 8 April 1310, on the conditions of return of the crown. Gentile also sent his confessor and chaplain, Franciscan lector Denis to the meeting. Ladislaus Kán finally agreed to give the Holy Crown to Charles.[23] On 27 August 1310, Archbishop Thomas put the Holy Crown on Charles's head in Székesfehérvár; thus, Charles's third coronation was performed in full accordance with customary law.[16] However, Charles' rule remained nominal in most parts of his kingdom.[16] Matthew Csák laid siege Buda in June 1311, and Ladislaus Kán declined to assist the king. In response to the attack, Gentile excommunicated Matthew Csák on 6 July 1311. Charles sent an army to invade Csák's domains in September, but it achieved nothing.[24] Pope Clement called back his papal legate to the Roman Curia in order to attend the Council of Vienne. Gentile issued his last charter in Pressburg on 9 September and thereafter left Hungary on 10 September 1311.[25] He resided in Wiener Neustadt already on 12 September 1311.[9]

Ecclesiastical affairs

His documents and charters during the period of his papal legation was published in the collection of "Acta legationis cardinalis Gentilis. Gentilis bibornok magyarországi követségének okiratai 1307–1311" by Hungarian historian Antal Pór in 1885. Beside his main task (securing Charles' accession to the throne), Gentile dealt extensively with the various affairs of the Church in Hungary. For instance, he judged over the controversial episcopal elections of Peter and Benedict in the dioceses of Pécs and Transylvania, which were heavily affected by the power aspirations of the oligarchs Henry Kőszegi and Ladislaus Kán, respectively. In addition, the chapter of Bosnia also requested the legate to confirm their bishop Gregory's election in December 1308.[7] Gentile ordered to annul the election of John as Abbot of Pannonhalma, because it did not comply with canon law. Finally, he absolved John from the incapacity of his physical disability due to the "troubled times".[13]

During his three-year legation in Hungary, Gentile convoked five national synods (Buda: November 1308, May 1309, July 1309; Pressburg: November 1309 [for the Polish prelates], May 1311).[7] Gentile bestowed the rule of Saint Augustine on behalf of the Holy See to the Order of Saint Paul the First Hermit on 13 December 1308, which meant the papal recognition of the Paulines as a monastic order.[26] The legate also confirmed the exemption of the Poor Clares monastery at Nagyszombat (present-day Trnava, Slovakia) from paying tithe in August 1309.[26] He appointed conservators to inspect monasteries of the Carthusians.[14] In his letter to Vincent, Archbishop of Kalocsa and his suffragans, the papal legate stated that he reserves the right to bestow all church benefice above worth 10 marks exclusively to himself. As a result, he appointed canons and other clergymen into their positions, overriding the Hungarian church hierarchy.[27] For instance, he donated a canonical emoluments in Pécs to his tax collector Rufinus, son of Albert.[28] In the name of his nephew Gualterius Raynaldi de Monteflorum, he launched a litigation against Henry of Wierzbna, the Bishop of Wrocław.[29] There is also a record of his decision to deprive a canon (Lucas of Vác) from his office due to his physical disability.[27] He also ordered to appoint deacons in the dioceses of Pécs and Zagreb, bypassing the authority of the bishops.[14] During his judicial activity, Gentile entrusted auditors from his own staff, largely neglecting the local Hungarian church personalities. His auditors were, for instance, his chaplains dr.iur.can. Filip de Sardinea, Johannes de Aretio (both of them were auditors general with wider authority), legate chamberlain dr.iur.can. Bonunsegna de Perusia and court cleric Casparus de Montefia.[30] At least altogether 52-member staff assisted Gentile's work in Hungary. His bailiff was his nephew Rogerius Mathei de Monteflorum. His physician was Fredericus de Bononia, while a certain Dionysius, penitentiary of the Franciscan Oder also belonged to his accompaniment.[31]

Cultural legacy

According to an inventory from 1322, Gentile possessed some Hungary-related books after his departure to Italy. Two of them were titled "decretum sancti Stephani regis Ungari" ("The Decrees of Saint Stephen, King of Hungary") and "Ungarorum hystorie" ("The history of the Hungarians"). French philologist Marie-Henriette Jullien de Pommerol argued the cardinal brought these works from Hungary. Historian László Veszprémy considered that Gentile used the two books to legally justify Charles' claim to the Hungarian throne and to study the Hungarian historical approach regarding the system of relations with the Holy See. Veszprémy argued the latter work was identical with a copy of the pre-14th-century Hungarian chronicle variant and became part of the collection of the papal library at Avignon under the title "cronica Ungarorum in pergameno cum postibus et corio albo in parvo forma".[32]

Later life

Arriving to Italy, Gentile participated in the Council of Vienne convened on 16 October 1311. There, he defended the memory of Pope Boniface VIII in a passionate speech.[2] After his arrival, Pope Clement charged Gentile with transfer of the papal treasures of Rome, the Patrimony of Saint Peter beyond the Alps to Avignon, the new seat of the popes. Gentile estimated that because of the struggle for power between the factions of the Guelphs and Ghibellines it was not safe to transport the treasures; thus the cardinal took the most valuable items of the papal treasure with him, leaving the rest in safe deposit in the sacristy of the Basilica of San Frediano, in Lucca. When the Italian mercenary Uguccione della Faggiuola conquered the town in 1314, the remaining papal treasures and the cardinal's possession were stolen.[2]

Gentile is known to have been in Siena, when a document dating to March 1312 testifies the cardinal paid 600 golden florins for the construction and fresco decoration of a chapel in the Lower Basilica of Saint Francis in Assisi. According to recent hypotheses, the unnamed sculptor-architect who built and decorated this chapel was also responsible for creating the monumental tomb of Gentile Portino's parents in Montefiore dell'Aso (Ascoli Piceno).[33] The San Martino Chapel, dedicated to Saint Martin of Tours, was decorated between 1317 and 1319 with ten frescoes depicting the saint's life by Simone Martini, who was hired by the cardinal presumably in Siena. At the beginning of June, Gentile went to Lucca, where he fell ill and died there in the following October, without arriving in Avignon.[1] The San Martino Chapel was intended to be Gentile's burial place, but was probably incomplete at the time of his death, thus he was buried in the neighboring Chapel of St. Louis. On 5 August 1313, Pope Clement ordered that the wealth of Gentile Portino should be assigned to Cardinal Vital du Four.[2]

References

- "Influential Figures: Cardinal Gentile Partino da Montefiore (1240 – 1312)". montefioredellaso.com. Retrieved 2019-07-19.

- "Montefiore O.F.M., Gentile da". Biographical Dictionary of the Cardinals of the Holy Roman Church. Retrieved 2019-07-19.

- Maléth 2020, p. 280.

- Kádár 2017, p. 146.

- Maléth 2020, p. 57.

- Engel 2001, pp. 129–130.

- Kovács 2013, p. 76.

- Kádár 2017, p. 147.

- Veszprémy 2013, p. 231.

- Maléth 2020, p. 56.

- Csukovits 2012, p. 60.

- Kádár 2017, pp. 153–155.

- Maléth 2020, p. 65.

- Maléth 2020, pp. 67–68.

- Kádár 2017, pp. 155–157.

- Engel 2001, p. 130.

- Csukovits 2012, p. 67.

- Kádár 2017, pp. 159–160.

- Kádár 2017, pp. 164–165, 167.

- Kádár 2017, pp. 178–179.

- Kádár 2017, p. 182.

- Kádár 2017, pp. 180–181.

- Kádár 2017, p. 184.

- Csukovits 2012, p. 78.

- Csukovits 2012, p. 65.

- Kovács 2013, p. 77.

- Kovács 2013, p. 81.

- Maléth 2020, p. 66.

- Maléth 2020, p. 69.

- Kovács 2013, p. 82.

- Maléth 2020, p. 73.

- Veszprémy 2013, pp. 232–233.

- Palozzi, L. (2013). Talenti provinciali: Il cardinale francescano Gentile Partino da Montefiore e un’aggiunta alla scultura umbra del Trecento, in Civiltà urbana e committenze artistiche al tempo del Maestro di Offida (secoli XIV-XV), ed. S. Maddalo et al. Rome: Istituto Storico Italiano per il Medioevo: 243-266.

Sources

- Csukovits, Enikő (2012). Az Anjouk Magyarországon. I. rész. I. Károly és uralkodása (1301‒1342) [The Angevins in Hungary, Vol. 1. Charles I and His Reign (1301‒1342)] (in Hungarian). MTA Bölcsészettudományi Kutatóközpont Történettudományi Intézet. ISBN 978-963-9627-53-6.

- Engel, Pál (2001). The Realm of St Stephen: A History of Medieval Hungary, 895–1526. I.B. Tauris Publishers. ISBN 1-86064-061-3.

- Gaffuri, Laura (2000). "Gentile da Montefiore (Gentilis de Monteflore)". Dizionario biografico degli italiani (in Italian). 53: 167–170.

- Kádár, Tamás (2017). "Harcban a koronáért. (II.) I. Károly (Róbert) király uralkodásának 1306–1310 közötti szakasza [Fight for the Crown. The Reign of Charles I (Robert) from 1306 to 1310]". Történeti Tanulmányok. Acta Universitatis Debreceniensis (in Hungarian). 25: 126–192. ISSN 1217-4602.

- Kovács, Viktória (2013). "Causae coram nobis ventilatae. Adalékok Gentilis de Monteflorum pápai legátus magyarországi egyházi bíráskodási tevékenységéhez (1308–1311) [Causae coram nobis ventilatae. Contributions to the Ecclesiastical Jurisdiction of the Papal Legate, Gentilis de Monteflorum (1308–1311)]". In Fedeles, Tamás; Font, Márta; Kiss, Gergely (eds.). Kor-Szak-Határ (in Hungarian). Pécsi Tudományegyetem. pp. 75–99. ISBN 978-963-642-518-0.

- Maléth, Ágnes (2020). A Magyar Királyság és a Szentszék kapcsolata I. Károly korában (1301–1342) [The Relationship of the Hungarian Kingdom and the Holy See in the time of Charles I (1301–1342)] (in Hungarian). Pécsi Tudományegyetem BTK TTI Középkori és Koraújkori Történeti Tanszék. ISBN 978-963-429-500-6.

- Rácz, György (2011). "Gentilis és Károly. Levélírás Pozsonyban, koronázás Fehérvárott. A papír megjelenése Magyarországon [Gentilis and Charles. Letter Writing in Pressburg, Coronation in Székesfehérvár. The Appearance of Paper in Hungary]". In Kerny, Terézia; Smohay, András (eds.). Károly Róbert és Székesfehérvár (in Hungarian). Székesfehérvári Egyházmegyei Múzeum. pp. 32–43. ISBN 978-963-87898-3-9.

- Veszprémy, László (2013). ""Történetünk küllôibe merész kézzel bele markola". Gentilis bíboros magyarországi olvasmányaihoz ["He Boldly Grasped the Spokes of the Wheel of our Nation's History". On the Readings of Cardinal Gentilis in Hungary]". Ars Hungarica (in Hungarian). 39 (2): 230–235. ISSN 0133-1531.