Geoarchaeology

Geoarchaeology is a multi-disciplinary approach which uses the techniques and subject matter of geography, geology, geophysics and other Earth sciences to examine topics which inform archaeological knowledge and thought. Geoarchaeologists study the natural physical processes that affect archaeological sites such as geomorphology, the formation of sites through geological processes and the effects on buried sites and artifacts post-deposition. Geoarchaeologists' work frequently involves studying soil and sediments as well as other geographical concepts to contribute an archaeological study. Geoarchaeologists may also use computer cartography, geographic information systems (GIS) and digital elevation models (DEM) in combination with disciplines from human and social sciences and earth sciences.[1] Geoarchaeology is important to society because it informs archaeologists about the geomorphology of the soil, sediment, and rocks on the buried sites and artifacts they are researching. By doing this, scientists are able to locate ancient cities and artifacts and estimate by the quality of soil how "prehistoric" they really are. Geoarchaeology is considered a sub-field of environmental archaeology because soil can be altered by human behavior, which archaeologists are then able to study and reconstruct past landscapes and conditions.

Techniques used

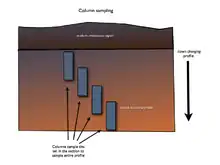

Column sampling

Column sampling is a technique of collecting samples from a section for analyzing and detecting the buried processes down the profile of the section. Narrow metal tins are hammered into the section in a series to collect the complete profile for study. If more than one tin is needed they are arranged offset and overlapping to one side so the complete profile can be rebuilt offsite in laboratory conditions.

Loss on ignition testing

Loss on ignition testing for soil organic content – a technique of measuring organic content in soil samples. Samples taken from a known place in the profile collected by column sampling are weighed then placed in a fierce oven which burns off the organic content. The resulting cooked sample is weighed again and the resulting loss in weight is an indicator of organic content in the profile at a certain depth. These readings are often used to detect buried soil horizons. A buried soil's horizons may not be visible in section and this horizon is an indicator of possible occupation levels. Ancient land surfaces especially from the prehistoric era can be difficult to discern so this technique is useful for evaluating an area's potential for prehistoric surfaces and archaeological evidence. Comparative measurements down the profile are made and a sudden rise in organic content at some point in the profile combined with other indicators is strong evidence for buried surfaces.

Near-surface geophysical prospection

Geophysical archaeological prospection methods are used to non-destructively explore and investigate possible structures of archaeological interest buried in the subsurface. Commonly used methods are:

- magnetometry

- ground-penetrating radar

- earth resistance measurements

- electromagnetic induction measurements (including metal detection and magnetic susceptibility surveys)

- sonar (sidescan, single-beam or multibeam sonar, sediment sonar) in underwater archaeology

Less commonly used geophysical archaeological prospection methods are:

- reflection or refraction seismic measurements

- gravity measurements

- thermography

Magnetic susceptibility analysis

The magnetic susceptibility of a material is a measure of its ability to become magnetised by an external magnetic field (Dearing, 1999). The magnetic susceptibility of a soil reflects the presence of magnetic iron-oxide minerals such as maghaematite; just because a soil contains a lot of iron does not mean that it will have high magnetic susceptibility. Magnetic forms of iron can be formed by burning and microbial activity such as occurs in top soils and some anaerobic deposits. Magnetic iron compounds can also be found in igneous and metamorphic rocks.

The relationship between iron and burning means that magnetic susceptibility is often used for:

- Site prospection, to identify areas of archaeological potential prior to excavation.

- Identifying hearth areas and the presence of burning residues in deposits.[2]

- Explaining whether areas of reddening are due to burning or other natural processes such as gleying (waterlogging).

The relationship between soil formation and magnetic susceptibility means that it can also be used to:

- Identify buried soils in depositional sequences.

- Identify redeposited soil materials in peat, lake sediments etc.

Phosphate and orthophosphate content with spectrophotometry

Phosphate in man-made soils derives from people, their animals, rubbish and bones. 100 people excrete about 62 kg of phosphate annually, with about the same from their rubbish. Their animals excrete even more. A human body contains about 650 g of PO

4 (500 g–80% in the skeleton), which results in elevated levels in burial sites. Most is quickly immobilised on the clay of the soil and 'fixed', where it can persist for thousands of years. For a 1 ha site this corresponds to about 150 kg PO

4 ha-1yr-1 about 0.5% to 10% of that already present in most soils. Therefore, it doesn't take long for human occupation to make orders of magnitude differences to the phosphate concentration in soil. Phosphorus exist in different 'pools' in the soil 1) organic (available), 2) occluded (adsorbed), 3) bound (chemically bound). Each of these pools can be extracted using progressively more aggressive chemicals. Some workers (Eidt especially), think that the ratios between these pools can give information about past land use, and perhaps even dating.

Whatever the method of getting the phosphorus from the soil into solution, the method of detecting it is usually the same. This uses the 'molybdate blue' reaction, where the depth of the colour is proportional to phosphorus concentration. In the lab, this is measured using a colorimeter, where light shining through a standard cell produces an electric current proportional to the light attenuation. In the field, the same reaction is used on detector sticks, which are compared to a colour chart.

Phosphate concentrations can be plotted on archaeological plans to show former activity areas, and is also used to prospect for sites in the wider landscape.

Particle size analysis

The particle size distribution of a soil sample may indicate the conditions under which the strata or sediment were deposited. Particle sizes are generally separated by means of dry or wet sieving (coarse samples such as till, gravel and sands, sometimes coarser silts) or by measuring the changes of the density of a dispersed solution (in sodium pyrophosphate, for example))of the sample (finer silts, clays). A rotating clock-glass with a very fine-grained dispersed sample under a heat lamp is useful in separating particles.

The results are plotted on curves which can be analyzed with statistical methods for particle distribution and other parameters.

The fractions received can be further investigated for cultural indicators, macro- and microfossils and other interesting features, so particle size analysis is in fact the first thing to do when handling these samples.

Trace element geochemistry

Trace element geochemistry is the study of the abundances of elements in geological materials that do not occur in a large quantity in these materials. Because these trace elements' concentrations are determined by a large number of particular situations under which a certain geological material is formed, they are usually unique between two locations which contain the same type of rock or other geological material.

Geoarchaeologists use this uniqueness in trace element geochemistry to trace ancient patterns of resource-acquisition and trade. For example, researchers can look at the trace element composition of obsidian artifacts in order to "fingerprint" those artifacts. They can then study the trace element composition of obsidian outcrops in order to determine the original source of the raw material used to make the artifact.

Clay mineralogy analysis

Geoarchaeologists study the mineralogical characteristics of pots through macroscopic and microscopic analyses. They can use these characteristics to understand the various manufacturing techniques used to make the pots, and through this, to know which production centers likely made these pots. They can also use the mineralogy to trace the raw materials used to make the pots to specific clay deposits.[3]

Ostracod analysis

Naturally occurring Ostracods in freshwater bodies are impacted by changes in salinity and pH due to human activities. Analysis of Ostracod shells in sediment columns show the changes brought about by farming and habitation activities. This record can be correlated with age dating techniques to help identify changes in human habitation patterns and population migrations.[4]

Archaeological geology

Archaeological geology is a term coined by Werner Kasig in 1980. It is a sub-field of geology which emphasises the value of earth constituents for human life.

See also

Notes

- Ghilardi, M. and Desruelles, S. (2008) “Geoarchaeology: where human, social and earth sciences meet with technology”. S.A.P.I.EN.S. 1 (2)

- Tite, M.S.; Mullins, C. (1971). "Enhancement of magnetic susceptibility of soils on archaeological sites". Archaeometry. 13 (2): 209–219. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4754.1971.tb00043.x.

- Druca, I. C. and Q. H. J. Gwynb (1997), From Clay to Pots: A Petrographical Analysis of Ceramic Production in the Callejón de Huaylas, North-Central Andes, Peru, Journal of Archaeological Science, 25, 707-718.

- "^ Manuel R. Palacios-Fest, "Nonmarine ostracode shell chemistry from ancient hohokam irrigation canals in central Arizona: A paleohydrochemical tool for the interpretation of prehistoric human occupation in the North American Southwest" Geoarchaeology, Volume 9 Issue 1, Pages 1 – 29, Published Online: 9 Jan 2007" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

References

- Slinger, A., Janse, H.. and Berends, G. 1980 . Natuursteen in monumenten. Zeist / Baarn Rijksdienst voor de Monumentenzorg.

- Kasig, Werner 1980. Zur Geologie des Aachener Unterkarbons (Linksrheinisches Schiefergebirge, Deutschland) — Stratigraphie, Sedimentologie und Palaeogeographie des Aachener Kohlenkalks und seine Bedeutung fuer die Entwicklung der Kulturlandschaft im Aachener Raum Aachen RWTH Fak Bergbau… "zur Erlangung…" =. Aachen RWTH.

- Jonghe, Sabine de -, Tourneur, Francis, Ducarme, Pierre, Groessens, Eric e.a. 1996 . Pierres à bâtir traditionnelles de la Wallonie - manuel de terrain. Jambes / Louvain la Neuve ucl, chab / dgrne / region wallonne

- Dreesen, Roland, Dusar, M. and Doperé, F., 2001 . Atlas Natuursteen in Limburgse monumentenx- 2nd print 320pp. . LIKONA ISBN 90-74605-18-4

- Dearing, J. (1999) Magnetic susceptibility. In, Environmental magnetism: a practical guide Walden, J., Oldfield, F., Smith, J., (Eds). Technical guide, No. 6. Quaternary Research Association, London, pp. 35–62.

External links

- The Laboratory of Geoarchaeology, Kazakhstan Information about Geoarchaeological work in Central Asia

- SASSA (Soil Analysis Support System for Archaeologists) Archived 2007-02-06 at the Wayback Machine