Geological deformation of Iceland

The geological deformation of Iceland is the way that the rocks of the island of Iceland are changing due to tectonic forces. The geological deformation explains the location of earthquakes, volcanoes, fissures, and the shape of the island. Iceland is the largest landmass (102,775 km²) situated on an oceanic ridge.[1] It is an elevated plateau of the sea floor, situated at the crossing of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge and the Greenland-Iceland-Faeroe Ridge.[2] It lies along the oceanic divergent plate boundary of North American Plate and Eurasian Plate. The western part of Iceland sits on the North American Plate and the eastern part sits on the Eurasian Plate. The Reykjanes Ridge of the Mid-Atlantic ridge system in this region crosses the island from southwest and connects to the Kolbeinsey Ridge in the northeast.[1]

Geological deformation of Iceland | |

|---|---|

Land deformation | |

.jpg.webp) Extensional structure, Þingvellir Graben, provides evidence for plate divergence in Iceland. | |

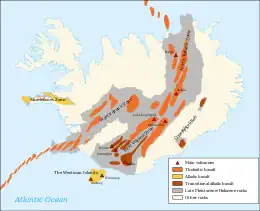

Fig 1. This figure shows the locations of the major deformation zones in Iceland. The thickest line represents the divergent plate boundary. Legend: RR, Reykjanes Ridge; RVB, Reykjanes Volcanic Belt; WVZ, West Volcanic Zone; MIB, Mid-Iceland Belt; SISZ, South Iceland Seismic Zone; EVZ, East Volcanic Zone; NVZ, North Volcanic Zone; TFZ, Tjörnes Fracture Zone; KR, Kolbeinsey Ridge; ÖVB, Öræfajökul Volcanic Belt; SVB, Snæfellsnes Volcanic Belt. The legend for the basalt regions is the same as below. | |

| Age | 25 million years |

| Formed by | Tectonic forces |

| Area | |

| • Total | 102,775 km² |

| Volcanic belt | Reykjanes |

Iceland is geologically young: all rocks there were formed within the last 25 million years.[3] It started forming in the Early Miocene sub-epoch, but the oldest rocks found at the surface of Iceland are from the Middle Miocene sub-epoch. Nearly half of Iceland was formed from a slow spreading period from 9 to 20 million years ago (Ma).[3]

The geological structures and geomorphology of Iceland are strongly influenced by the spreading plate boundary and the Iceland hotspot. The buoyancy of the deep-seated mantle plume underneath has uplifted the Iceland Basalt Plateau to as high as 3000 meters. The hot spot also produces high volcanic activity on the plate boundary.[1]

There are two major geologic and topographic structural trends in Iceland. One strikes northeast in Southern Iceland and strikes nearly north in northern Iceland. The other one strikes approximately west-northwest. Altogether they produce a zigzag pattern. The pattern is shown by faults, volcanic fissures, valleys, dikes, volcanoes, grabens and fault scarps.[3]

Deformation of Iceland

The geological deformation of Iceland is mainly caused by the active spreading of the mid-oceanic ridge. Extensional cracks and transform faults are found perpendicular to the spreading direction.[1] The transform-fault zones are also known as fracture zones. These fracture zones allow large volumes of lava to be erupted. On the surface of Iceland, linear volcanic fissures formed along the rifts and appear in a swarm-like pattern. They are connected by fracture zones, forming the volcanic zones.[3]

Plate boundary deformation zone

Crustal movements have created two plate boundary deformation zones between the major plates, the North American Plate and the Eurasian Plate.[1]

In northern Iceland, the width of the deformation zone is about 100 km wide. It accumulates strain which come from rifting episodes and larger earthquakes.[1]

In southern Iceland, the block located along the plate boundary is identified as a microplate and is named the Hreppar Block. The deformation zone is relatively small since it has no significant evidence of active deformation, earthquakes or volcanism. The northern boundary of the block is linked to the Central Iceland Volcanic Zone (CIVZ), where diffuse volcanism occur. The southern boundary of the block is termed the South Iceland Seismic Zone, where strike-slip earthquakes can occur.[1]

Transform fault zones

There are two major and active transform faults zones striking west-northwest in northern and southern Iceland.[4] Two large fracture zones, associated with the transform faults, namely Tjörnes and Reykjanes Fracture Zones are found striking about 75°N to 80°W.[3]

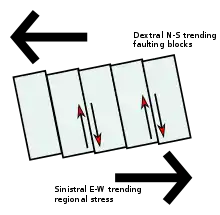

Bookshelf faulting

Stress is built up during the spreading movements at the plate boundary. The accumulated stress in transform fault zones is released during strike-slip earthquakes. The transform fault is induced by strike-slip motion that is transverse to the fault zone. The blocks between the faults are slightly rotated afterwards. A diagram (fig.2) is shown to illustrate this phenomenon. Since the rotation of the blocks is similar to a line of books leaning on a bookshelf, it is termed "bookshelf faulting".[1]

Bookshelf faulting is an indicator of the young geological history of the fault zones. It is common in the Reykjanes Fracture Zones.

Other evidence

Besides bookshelf faulting, the presence of the Icelandic fault zones are supported by seismological evidence. In Iceland, deformation usually concentrates over a zone of finite width. Thus, earthquakes usually occur along the active fracture zones between ridge crests.[4] Most earthquake activity in Iceland is focused in the transform faulting zones near the north and south coast.

Tjörnes Fracture Zone

The Tjörnes Fracture Zone (TFZ) is a tectonically complicated area. It connects the North Iceland Volcanic Zone (NVZ) and the southern end of the Kolbeinsey Ridge.[5] This 50 km wide fracture zone is characterised by seismic activity, crustal extension and transform faulting.[3] The volcanic fissure swarms of the Northern Volcanic Zone are connected to the southern end of Tjörnes Fracture Zone. For example, its southeast end is connected to the Krafla fissure swarm.

The main structural components of the Tjörnes Fracture Zone can be divided into three parts which trend from northwest to southeast, the Grímsey seismic zone, the Húsavík-Flatey fault zone and the Dalvík seismic zone.[5] The Tjörnes Fracture Zone shows a huge spatial difference in seismic activity. For example, the westernmost part of the Tjörnes Fracture Zone shows seismic activity, but a few larger earthquakes (>M=5.5) also appear in the zone.[5]

The complexity in the Tjörnes Fracture Zone can be generally explained by the magmatic processes and plate motions. The velocity of the divergent plate motion, estimated to be 18.9 mm/year ±0.5 mm/year, is strongly affected by the Icelandic mantle plume underneath central Iceland.[6] Volcanic activity can be found in the Dalvík seismic zone and southern tip of the Kolbeinsey Ridge.[7]

South Iceland Seismic Zone

The South Iceland Seismic Zone (SISZ), also known as the Reykjanes Fracture Zone (or Zones), is 75 to 100 km wide, and strikes northeast to southwest in southwestern Iceland. There are several approximately 40 km right lateral offsets of the ridge crest. The offsets create a transform fault zone connecting the Eastern Volcanic Zone and the Reykjanes.[4]

There is a significant change in the age and lithology of the volcanoes in a north-south direction near Reykjanes peninsula due to bookshelf faulting. Bookshelf faulting is common in the South Iceland Seismic Zone. Since the transform motion in the South Iceland Seismic Zone is left-lateral, right-lateral faulting would occur and rotation of blocks would appear counterclockwise. The sequential occurrence of major earthquakes in the South Iceland Seismic Zone provided evidence of bookshelf faulting. Within a single event, earthquakes begin in the eastern part of the South Iceland Seismic Zone with larger magnitudes and end up with smaller magnitudes in western part of the zone.[1][4]

In the transform fault zones of Iceland, earthquakes usually occur on small scales (micro-earthquakes) due to plate straining and pore fluid pressure. A large amount of pore fluid pressure migrates from the brittle–ductile transition zone (~10 km) to the lithostatic boundary at 3 km depth.[5] Large scale seismic activity is triggered if the pressure cannot pass through the transition zone. Small scale earthquakes are also released locally in or above the migration path.[5]

In 2000, a large earthquake (M=6.6) occurred in the South Iceland Seismic Zone. During this event, small scale earthquakes concentrated narrowly and linearly around the transform fault planes.[1][8] Thus, with the same method, small scale earthquakes are also used to identify fault planes in the Tjörnes Fracture Zone.

Volcanic rift zones

Rift jump model

The evolution of the Icelandic volcanic rift zones can be explained by the rift jump model.[9]

Synform folding is expected to occur at the active rift axis. However, distinctive reversals in dip directions are found in south-western Iceland which indicate an anticline. It is believed that the relative positions of the Icelandic hot spot and the active rift spreading axis have changed with time. Assuming the Icelandic mantle plume is stationary, the spreading axis must have changed position.[9]

The spreading axis migrates westward at a rate of 0.3 cm/year. After the active spreading axis has moved away from the plume, the mantle plume would adjust the position of the axis and forms a new rift closer to its centre. The migrated axis would gradually become extinct.[1]

There are three major volcanic zones in Iceland, which are the Northern, Eastern and Western Volcanic Zones (NVZ, EVZ, WVZ), and all of which are currently active. The volcanic rift zones cross the island from southwest to northeast. Each zone consists of 20–50 km wide belts and is characterised by active volcanoes, numerous normal faults, a high temperature geothermal field and fissure swarms.[10] The Eastern Volcanic Zone will eventually take over the Western Volcanic Zone according to the rift jump process.

Northern Volcanic Zone

The 50 km wide Northern Volcanic Zone (NVZ) is composed of five volcanic systems arranged zigzag-like along the mid-Atlantic plate boundary. It shows quite low seismic activity. The volcanic activity is confined to the Krafla central volcano and its associated fissure swarms.[4]

The Krafla central volcano is not distinctive within the volcanic rift zone. Fissure swarms of the Krafla spread away from the magma chamber and magma flows along the swarms to the north and south of the volcano. Eruptive fissures within the fissure swarms are most common within 20–30 km distance from the central volcanoes. Fractures within the fissure swarms are common at up to a distance of 70–90 km from the central volcano.[4]

Fractures within the fissure swarms are generally subparallel to each other. Irregular fracture patterns are found where the Húsavík transform fault meets the fissure swarms, which indicates interaction between the fissure swarms and the strike-slip faults.[4]

Eastern Volcanic Zone

The Eastern Volcanic Zone (EVZ) is located in south-east Iceland. It connects to the South Iceland Seismic Zone and NVC in its western and northern end respectively. Seismic activity focuses in the Vatnajökull Glacier area which is the accepted location of the Icelandic hot spot.[1]

Deformed structures, including northeast trending eruptive fissure swarms and normal faults, can be found in Eastern Volcanic Zone.[11] Long hyaloclastite ridges, formed by subglacial eruptions during the last glacial period, are distinctive structures in the Eastern Volcanic Zone. Compared with Western Volcanic Zone, eruptive fissure swarms and hyaloclastite ridges are generally longer in the Eastern Volcanic Zone.[1] During the past glacial period, a huge volume of basaltic eruptions occurred, producing the long volcanic fissure swarms. The Eastern Volcanic Zone is geologically young, as mentioned above, the Eastern Volcanic Zone will eventually take over the Western Volcanic Zone according to the rift jump process model.[1]

Western Volcanic Zone (WVZ)

The Western Volcanic Zone is located to the north of the South Iceland Seismic Zone, where its northern end connects to the Langjökull area.[1] It has been the active propagating rift in the last 7 million years.[12] Volcanic fissures and normal faulting are common features in the southern part of the Western Volcanic Zone. In the northern part of the Western Volcanic Zone, normal faulting is still common but volcanic fissures become less dominant.

Shield volcanoes are also observed in this zone. Þingvellir Graben is clear evidence as proof of divergent plate movement in Iceland. It shows a clear extensional feature.[1]

References

- Einarsson, P. (2008). "Plate boundaries, rifts and transforms in Iceland". Jökull. 58 (12): 35–58.

- Árnadóttir, T.; Geirsson, H.; Jiang, W. (2008). "Crustal deformation in Iceland: Plate spreading and earthquake deformation". Jökull. 58: 59–74.

- Ward, P. L. (1971). "New Interpretation of the Geology of Iceland". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 82 (11): 2991–3012. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1971)82[2991:NIOTGO]2.0.CO;2.

- Einarsson, P. (1991). "Earthquakes and present-day tectonism in Iceland". Tectonophysics. 189 (1–4): 261–279. Bibcode:1991Tectp.189..261E. doi:10.1016/0040-1951(91)90501-I.

- Stefansson, R.; Gudmundsson, G. B.; Halldorsson, P. (February 2008). "Tjörnes fracture zone. New and old seismic evidences for the link between the North Iceland rift zone and the Mid-Atlantic ridge". Tectonophysics. 447 (1–4): 117–126. Bibcode:2008Tectp.447..117S. doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2006.09.019.

- Stefánsson, R.; Halldórsson, P. (September 1988). "Strain release and strain build-up in the south Iceland seismic zone". Tectonophysics. 152 (3–4): 267–276. Bibcode:1988Tectp.152..267S. doi:10.1016/0040-1951(88)90052-2.

- Riedel, C.; Schmidt, M.; Botz, R.; Theilen, F. (December 2001). "The Grimsey hydrothermal field offshore North Iceland: crustal structure, faulting and related gas venting". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 193 (3–4): 409–421. Bibcode:2001E&PSL.193..409R. doi:10.1016/S0012-821X(01)00519-2.

- Stefánsson, R., Guðmundsson, G. B., & Roberts, M. J. (2006). Long-term and short-term earthquake warnings based on seismic information in the SISZ. Veðurstofa Íslands.

- Sæmundsson, K. (1974). "Evolution of the Axial Rifting Zone in Northern Iceland and the Tjörnes Fracture Zone". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 85 (4): 495–504. Bibcode:1974GSAB...85..495S. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1974)85<495:EOTARZ>2.0.CO;2.

- Flóvenz, Ó. G.; Saemundsson, K. (1993). "Heat flow and geothermal processes in Iceland". Tectonophysics. 225 (1–2): 123–138. Bibcode:1993Tectp.225..123F. doi:10.1016/0040-1951(93)90253-G.

- Þórarinsson, S., Sæmundsson, K., & Williams, R. S. (1973). ERTS-1 image of Vatnajökull: analysis of glaciological, structural, and volcanic features.

- Kristjánsson, L.; Jónsson, G. (1998). "Aeromagnetic results and the presence of an extinct rift zone in western Iceland". Journal of Geodynamics. 25 (1–2): 99–108. Bibcode:1998JGeo...25...99K. doi:10.1016/S0264-3707(97)00009-4.