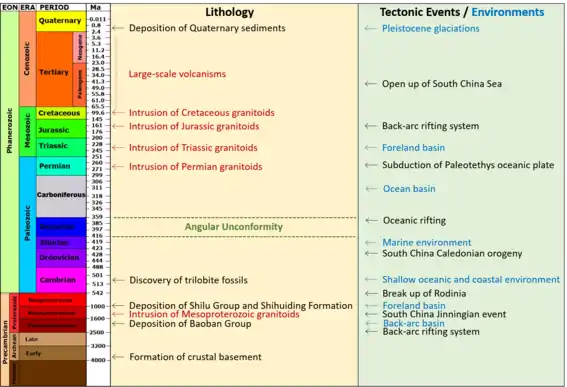

Geology of Hainan Island

Hainan Island, located in the South China Sea off the Chinese coast and separated from mainland China by the Qiongzhou Strait, has a complex geological history that it has experienced multiple stages of metamorphism, volcanic and intrusive activities, tectonic drifting and more.[1] The oldest rocks, the Proterozoic metamorphic basement, are not widely exposed, but mostly found in the western part of the Island.[1]

Hainan is mainly covered by igneous rocks emplaced from Permian through Cretaceous periods.[2] Structurally, there are two main sets of faults, one trending east and the other northeast.[2] The formation of the oldest fault, Gezhen shear fault, can even be dated back to the Precambrian times.[1]

The multiple stages of granitoid emplacements through its geological history have made Hainan Island rich in various types of ore deposits, including gold, molybdenum, lead, zinc, silver, etc.[3] According to the distribution of the ore deposits, the Island is generally divided into 6 ore-forming provinces.[3] Regarding the present geological activities, small earthquakes are still happening, while the volcanoes are inactive.[4]

Lithology and geological setting

Precambrian (older than 539 million years ago)

The Precambrian rock layers are not well exposed in Hainan Island where the outcrops are mainly found in its western part.[1][2] The crustal basement of the Island had an earliest age probably up to ca. 4000 to 3800 Ma.[7] The continental crust was then reworked in the later geological history. The Paleoproterozoic or older basement identified with the age of ca. 2560 Ma showed granulite facies metamorphism which mainly had an assemblage of gneissic amphibolite, charnockite and granulite.[8]

Baoban Group

The Baoban Group generally showed greenschist and amphibolite facies metamorphism which could also be separately identified as the Upper Ewenling Formation and the Lower Gezhencun Formation.[2]

During Paleoproterozoic and Mesoproterozoic, the Island was in a spreading arc basin system.[8] The rifting provided a depositional environment for the Baoban Group in ca. 1800–1450 Ma.[1] It was then intruded by Mesoproterozoic granites at ca. 1450–1430 Ma.[1][2] This was evidenced by the protolith of the Group, being interlayers of clastic-sedimentary rocks, pyroclastic and volcanic rocks which were mafic to intermediate in nature.[2] The regional metamorphism experienced by the Baoban Group was caused by the South China Jinningian event in which the Cathaysia Block fused with the Yangtze Block in Late Mesoproterozoic.[2] The event also led to deposition of Shilu Group and Shihuiding Formation.

Shilu Group and Shihuiding Formation

The Shilu Group was composed of siliciclastic and carbonate sedimentary rocks from shallow oceanic rifting environment with low grade metamorphism.[7]

Conformably lying above the Shilu Group was the Shihuiding Formation which was generally low-grade, siliciclastic rocks deposited in foreland basin.[7] The sedimentation took place in the period between Late Mesoproterozoic and Early Neoproterozoic. The rocks were then regionally metamorphosed in the late South China Jinningian event.[1]

Cambrian (539-48 million years ago)

The Cambrian rocks are exposed in the Southern Hainan Island which was composed of fine-grained shale and limestone deposited in shallow oceanic and coastal environment.[10]

In this layer of rocks, trilobite fossils were identified that when comparing them with those discovered in Queensland, Australia, geologists found the two were actually associated with each other,[11] hence this relationship is used to prove for the tectonic movement of Hainan Island at this geological time. This shows that after the break up of Rodinia at the end of Neoproterozoic, Hainan Island as part of the South China Block drifted towards the Australian continental plate, resulting in a comparable trilobite fossils record in both places.[1] At the stage of Rodinia breakup, the Cathaysia Block and the Yangtze Block were drifted apart.[12]

Ordovician (485-444 million years ago)

Ordovician rocks from the Northern and Southern Hainan Island show different characteristics. Rocks in the southern areas were sedimentary rocks deposited at the landward side of a coast, with distinctive features of having different grain sizes from black shale, lithic sandstone to conglomerate, as well as having both siliciclastic sedimentary rocks and limestones.[10]

On the other hand, Ordovician rocks found in the northern areas were interlayers of fine-grained siliciclastic rocks deposited in marine environment, extrusive igneous and pyroclastic rocks.[10] The volcaniclastic rocks were exhibiting low-grade metamorphism. These Ordovician rocks lied on top of the Cambrian rocks without unconformity.[2]

Silurian (444-419 million years ago)

Continuous rock records were found from Ordovician to Silurian Periods. Silurian rocks were mainly composed of interlayers of tuffaceous rocks and fine-grained clastic rocks formed in marine environment.[10] The rocks were metamorphosed in which some showed phyllitic characteristics.[10]

As in Cambrian, the Cathaysia Block and the Yangtze Block were drifted apart at the stage of Rodinia breakup.[12] During Middle Ordovician to Late Silurian, these two previously drifted apart blocks were collided with each other again, forming the large South China Block.[7] This event is referred as the South China Caledonian orogeny which probably took place in 430–400 Ma.[13] There exhibited an angular unconformity in high angles between the Silurian rocks and the Carboniferous rocks in which the Devonian units were missing.[10]

Carboniferous and Permian (359-252 million years ago)

Above the angular unconformity, the Carboniferous and Permian units lied conformably with each other, both having similar characteristics in the rock layers. They showed low-grade metamorphism in siliciclastic and carbonate sedimentary rocks deposited in shallow to deep marine environment with fine-to-medium grain size.[2] Also, there were granites (syenogranites and monzogranites) intruded at the age of ca. 300–250 Ma.[14] They were generally seen with foliations as well.

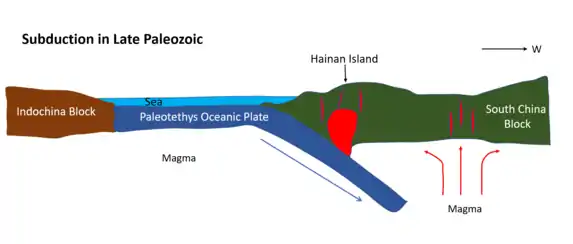

In Northern Hainan, there is a prominent fault, the Changjiang-Qionghai fault, along which shows the traces where the oceanic basin rifted apart under consistent extension in Late Paleozoic.[1] The Cambrian and Permian units were then deposited in the basin. Also, it is suggested that from the Late Devonian to Permian, Hainan Island as part of the South China Block drifted towards the Southeast Asian crustal plate in the north, breaking away from the East Gondwana.[15] As a result, there was an unconformity between the Paleozoic and the Mesozoic units.

Mesozoic (251-66 million years ago)

At around ca. 250 Ma, the oceanic basin was closed that the Paleo-Tethyan oceanic crust disappeared and the supercontinent Pangea was shaped.[1] The two massive masses adjacent to the oceanic basin then collided towards each other, forming Shilu mélange.[1]

Triassic (251-201 million years ago)

There are few traces of Early Triassic units found in Hainan Island. The rocks showed a range of grain sizes from fine-grained materials, such as siltstones and argillites, to detritus-bearing sandstones to course-grained materials such as conglomerates.[10] This suggested a foreland basin as its depositional environment.[1] At the same time, there was also intrusive activities at Early Mesozoic ca. 250–200 Ma, majorly producing granites (syenogranites and monzogranites).[14]

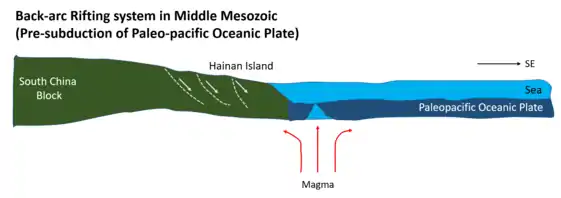

Jurassic and Cretaceous (201-66 million years ago)

In Middle-Jurassic, Hainan Island was in place at the back-arc rifting system.[16] Until Early Cretaceous, the Paleo-pacific oceanic plate was then subducted under the South China Block in the northwest.[16] As a result, the intrusive activities took place frequently as well.

The granitoids produced in Jurassic, ca. 173–150 Ma, had similar composition with those produced in Triassic.[14] The Cretaceous units are well exposed on Hainan Island. It can be divided into five stratigraphical units according to the geological sequence.[2] The rocks were mainly igneous in nature, including granites, andesites, dacites, rhyolites, mafic dykes, etc.[2] It is researched that the granitoid intrusive rocks had an age of ca. 131–73 Ma.[14]

Under the continuous extension system, there were large-scale volcanisms taken place during Late Cretaceous to Cenozoic.[1]

Cenozoic (66 million years ago -present)

In Cenozoic, South China Sea was opened, placing Hainan Island in the environment with large-scale volcanisms.[2] As a result, volcanic rocks, typically basalt, are the most prominent rock type in this period of time which are now mainly exposed in the northern part of the Island.[1]

Structure

There are dominantly two sets of fault system existed in Hainan Island, one set was trending east and the other was trending northeast.[2] Wangwu-Wenchang fault, Changjiang-Qionghai fault, Jianfeng-Diaoluo fault and Jiusuo-Lingshui fault are the major east-trending faults, while Gezhen shear fault and Baisha fault are the dominant northeast-trending faults on the Island.[1]

Each of the faults has its own geological influence to the present rock unit distributions and structures. For example, with the formation of Gezhen shear fault in South China Jinningian event, the Precambrian rock units were exposed in the Western Hainan Island.[1] Changjiang-Qionghai fault recorded the rifting of the oceanic basin in Late Paleozoic.[1]

Regarding the Gezhen shear fault, it transformed from ductile shearing in the beginning to brittle-ductile and finally to brittle shearing through several tectonic events.[2] To be specific, it was ductile in nature during the South China Caledonian orogeny in which the large South China Block was formed.[2] It then became brittle-ductile in nature in Late Paleozoic to Early Mesozoic when the Paleo-Tethyan oceanic basin was closed.[2] At last, the Gezhen shear fault transformed to brittle shearing in Late Mesozoic.[2]

Ore deposits

Due to the multiple stages of granitoid emplacements through its geological history, they have made Hainan Island rich in various types of ore deposits, including gold, molybdenum, lead, zinc, silver, etc.[3] Here will highlight the formation of gold and molybdenum deposits.

It is verified that Hainan Island processes more than 143 tons of gold deposits which are formed in Mesozoic Era in response to the subduction of Paleotethys oceanic plate and its subsequence intrusion of granitoids.[2] The deposits are generally found along the detachment faults that are closely related to folding and deformation on the Island, while they are hosted by the metamorphosed volcanoclastic rocks ranging from the Precambrian to Paleozoic Era.[2]

Hainan Island is also an important producer of molybdenum. The molybdenum deposits are generally formed by the granitoid emplacements during Cretaceous Period.[1] According to the chemical analysis of the deposits, they can be further divided into three stages of depositions.[1]

Present geological activity

In general, minor earthquake activity continues today. It is recorded by the Global Positioning System that there is a horizontal movement of the island in southeast direction at a rate of around 4.01 to 6.70 mm per year, while the vertical movement causing the island to uplift is at an overall rate of 2.4 mm per year.[2] Different parts of the Island have different velocities in vertical movements.[2]

In the northern part of Hainan Island, there were approximately 100 volcanoes producing lava which covered more than 4000 km2 of the area mainly in Quaternary and some in Tertiary Period.[2] At present, the volcanos are estimated to be inactive.[2]

References

- Xu, D. R., Wu, C. J., Hu, G. C., Chen, M. L., Fu, Y. R., Wang, Z. L., ... & Hollings, P. (2016). "Late Mesozoic molybdenum mineralization on Hainan Island, South China: Geochemistry, geochronology and geodynamic setting". Ore Geology Reviews. 72: 402–433. doi:10.1016/j.oregeorev.2015.07.023.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Xu, D., Wang, Z., Wu, C., Zhou, Y., Shan, Q., Hou, M., ... & Zhang, X. (2017). "Mesozoic gold mineralization in Hainan Province of South China: Genetic types, geological characteristics and geodynamic settings". Journal of Asian Earth Sciences. 137: 80–108. Bibcode:2017JAESc.137...80X. doi:10.1016/j.jseaes.2016.09.004.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - SHEN, Rui-wen; HAl, Tao (2011). "On the Relation of Magmatism with Ore-formation in the Hainan Island". 四川地质学报. 31 (4): 391–394. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1006-0995.2011.04.003.

- Hu, Yaxuan; Hao, Ming; Ji, Lingyun; Song, Shangwu (2016). "Three-dimensional crustal movement and the activities of earthquakes, volcanoes and faults in Hainan Island, China". Geodesy and Geodynamics. 7 (4): 284–294. doi:10.1016/j.geog.2016.05.008.

- Zhou, Yun; Liang, Xinquan; Kröner, Alfred; Cai, Yongfeng; Shao, Tongbin; Wen, Shunv; Jiang, Ying; Fu, Jiangang; Wang, Ce (2015). "Late Cretaceous lithospheric extension in SE China: Constraints from volcanic rocks in Hainan Island". Lithos. 232: 100–110. Bibcode:2015Litho.232..100Z. doi:10.1016/j.lithos.2015.06.028.

- Xu, Deru; Wang, Zhilin; Wu, Chuanjun; Zhou, Yueqiang; Shan, Qiang; Hou, Maozhou; Fu, Yangrong; Zhang, Xiaowen (2017). "Mesozoic gold mineralization in Hainan Province of South China: Genetic types, geological characteristics and geodynamic settings". Journal of Asian Earth Sciences. 137: 80–108. Bibcode:2017JAESc.137...80X. doi:10.1016/j.jseaes.2016.09.004.

- Zou, S., Yu, L., Yu, D., Xu, D., Ye, T., Wang, Z., ... & Liu, M. (2017). "Precambrian continental crust evolution of Hainan Island in South China: Constraints from detrital zircon Hf isotopes of metaclastic-sedimentary rocks in the Shilu Fe-Co-Cu ore district". Precambrian Research. 296: 195–207. Bibcode:2017PreR..296..195Z. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2017.04.020.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Zhang, Y. M. (1997). "The Precambrian crustal tectonic evolution in Hainan Island". Earth Science. 22: 395–400.

- Wang, Zhilin; Xu, Deru; Hu, Guocheng; Yu, Liangliang; Wu, Chuanjun; Zhang, Zhaochong; Cai, Jianxin; Shan, Qiang; Hou, Maozhou (2015). "Detrital zircon U–Pb ages of the Proterozoic metaclastic-sedimentary rocks in Hainan Province of South China: New constraints on the depositional time, source area, and tectonic setting of the Shilu Fe–Co–Cu ore district". Journal of Asian Earth Sciences. 113: 1143–1161. Bibcode:2015JAESc.113.1143W. doi:10.1016/j.jseaes.2015.04.014.

- HBGMR (Hainan Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources) (1997). Lithostratigraphy of Hainan Province. The Press of the China University of Geosciences, Wuhan. pp. 1–125.

- Zeng, Q. L., Yuan, C. L., Guo, Z. M., Lin, J., Wu, W., Cai, D., ... & Wang, W. (1992). Fundamental Geological Investigation of Sanya, Hainan Island. The Press of the China University of Geosciences, Wuhan. pp. 1–169.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Pirajno F. (2013). Yangtze Craton, Cathaysia and the South China Block. In: The Geology and Tectonic Settings of China's Mineral Deposits. Springer, Dordrecht.

- Wang, Y., F. Zhang, W. Fan, G. Zhang, S. Chen, P. A. Cawood, and A. Zhang (2010). "Tectonic setting of the South China Block in the early Paleozoic: Resolving intracontinental and ocean closure models from detrital zircon U-Pb geochronology". Tectonics. 29 (6): TC6020. Bibcode:2010Tecto..29.6020W. doi:10.1029/2010TC002750. S2CID 129470561.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - HBG (Hainan Bureau of Geology) (2016). Geology of Hainan Province. Geological Publishing House, Beijing.

- Metcalfe, I. (2013). "Gondwana dispersion and Asian accretion: tectonic and palaeogeographic evolution of eastern Tethys". Journal of Asian Earth Sciences. 66: 1–33. Bibcode:2013JAESc..66....1M. doi:10.1016/j.jseaes.2012.12.020.

- Zhou, B. X., Sun, T., Shen, W., Shu, L., & Niu, Y. (2006). "Petrogenesis of Mesozoic granitoids and volcanic rocks in South China: a response to tectonic evolution". Episodes. 29 (1): 26–33. doi:10.18814/epiiugs/2006/v29i1/004.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)