Geoneutrino

A geoneutrino is a neutrino or antineutrino emitted in decay of radionuclide naturally occurring in the Earth. Neutrinos, the lightest of the known subatomic particles, lack measurable electromagnetic properties and interact only via the weak nuclear force when ignoring gravity. Matter is virtually transparent to neutrinos and consequently they travel, unimpeded, at near light speed through the Earth from their point of emission. Collectively, geoneutrinos carry integrated information about the abundances of their radioactive sources inside the Earth. A major objective of the emerging field of neutrino geophysics involves extracting geologically useful information (e.g., abundances of individual geoneutrino-producing elements and their spatial distribution in Earth's interior) from geoneutrino measurements. Analysts from the Borexino collaboration have been able to get to 53 events of neutrinos originating from the interior of the Earth.[1]

Most geoneutrinos are electron antineutrinos originating in

β−

decay branches of 40K, 232Th and 238U. Together these decay chains account for more than 99% of the present-day radiogenic heat generated inside the Earth. Only geoneutrinos from 232Th and 238U decay chains are detectable by the inverse beta-decay mechanism on the free proton because these have energies above the corresponding threshold (1.8 MeV). In neutrino experiments, large underground liquid scintillator detectors record the flashes of light generated from this interaction. As of 2016 geoneutrino measurements at two sites, as reported by the KamLAND and Borexino collaborations, have begun to place constraints on the amount of radiogenic heating in the Earth's interior. A third detector (SNO+) is expected to start collecting data in 2017. JUNO experiment is under construction in Southern China. Another geoneutrino detecting experiment is planned at the China Jinping Underground Laboratory.

History

β−

decay of a neutron into a proton, electron, and electron antineutrino via an intermediate

W−

boson.

Neutrinos were hypothesized in 1930 by Wolfgang Pauli. The first detection of antineutrinos generated in a nuclear reactor was confirmed in 1956.[2] The idea of studying geologically produced neutrinos to infer Earth's composition has been around since at least mid-1960s.[3] In a 1984 landmark paper Krauss, Glashow & Schramm presented calculations of the predicted geoneutrino flux and discussed the possibilities for detection.[4] First detection of geoneutrinos was reported in 2005 by the KamLAND experiment at the Kamioka Observatory in Japan.[5][6] In 2010 the Borexino experiment at the Gran Sasso National Laboratory in Italy released their geoneutrino measurement.[7][8] Updated results from KamLAND were published in 2011[9][10] and 2013,[11] and Borexino in 2013[12] and 2015.[13]

Geological motivation

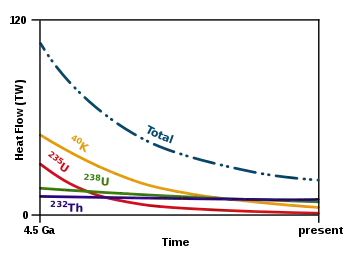

The Earth's interior radiates heat at a rate of about 47 TW (terawatts),[15] which is less than 0.1% of the incoming solar energy. Part of this heat loss is accounted for by the heat generated upon decay of radioactive isotopes in the Earth interior. The remaining heat loss is due to the secular cooling of the Earth, growth of the Earth's inner core (gravitational energy and latent heat contributions), and other processes. The most important heat-producing elements are uranium (U), thorium (Th), and potassium (K). The debate about their abundances in the Earth has not concluded. Various compositional estimates exist where the total Earth's internal radiogenic heating rate ranges from as low as ~10 TW to as high as ~30 TW.[16][17][18][19][20] About 7 TW worth of heat-producing elements reside in the Earth's crust,[21] the remaining power is distributed in the Earth mantle; the amount of U, Th, and K in the Earth core is probably negligible. Radioactivity in the Earth mantle provides internal heating to power mantle convection, which is the driver of plate tectonics. The amount of mantle radioactivity and its spatial distribution—is the mantle compositionally uniform at large scale or composed of distinct reservoirs?—is of importance to geophysics.

The existing range of compositional estimates of the Earth reflects our lack of understanding of what were the processes and building blocks (chondritic meteorites) that contributed to its formation. More accurate knowledge of U, Th, and K abundances in the Earth interior would improve our understanding of present-day Earth dynamics and of Earth formation in early Solar System. Counting antineutrinos produced in the Earth can constrain the geological abundance models. The weakly interacting geoneutrinos carry information about their emitters’ abundances and location in the entire Earth volume, including the deep Earth. Extracting compositional information about the Earth mantle from geoneutrino measurements is difficult but possible. It requires a synthesis of geoneutrino experimental data with geochemical and geophysical models of the Earth. Existing geoneutrino data are a byproduct of antineutrino measurements with detectors designed primarily for fundamental neutrino physics research. Future experiments devised with a geophysical agenda in mind would benefit geoscience. Proposals for such detectors have been put forward.[22]

Geoneutrino prediction

Calculations of the expected geoneutrino signal predicted for various Earth reference models are an essential aspect of neutrino geophysics. In this context, "Earth reference model" means the estimate of heat producing element (U, Th, K) abundances and assumptions about their spatial distribution in the Earth, and a model of Earth's internal density structure. By far the largest variance exists in the abundance models where several estimates have been put forward. They predict a total radiogenic heat production as low as ~10 TW[16][23] and as high as ~30 TW,[17] the commonly employed value being around 20 TW.[18][19][20] A density structure dependent only on the radius (such as the Preliminary Reference Earth Model or PREM) with a 3-D refinement for the emission from the Earth's crust is generally sufficient for geoneutrino predictions.

The geoneutrino signal predictions are crucial for two main reasons: 1) they are used to interpret geoneutrino measurements and test the various proposed Earth compositional models; 2) they can motivate the design of new geoneutrino detectors. The typical geoneutrino flux at Earth's surface is few × 106 cm−2⋅s−1.[24] As a consequence of (i) high enrichment of continental crust in heat producing elements (~7 TW of radiogenic power) and (ii) the dependence of the flux on 1/(distance from point of emission)2, the predicted geoneutrino signal pattern correlates well with the distribution of continents.[25] At continental sites, most geoneutrinos are produced locally in the crust. This calls for an accurate crustal model, both in terms of composition and density, a nontrivial task.

Antineutrino emission from a volume V is calculated for each radionuclide from the following equation:

where dφ(Eν,r)/dEν is the fully oscillated antineutrino flux energy spectrum (in cm−2⋅s−1⋅MeV−1) at position r (units of m) and Eν is the antineutrino energy (in MeV). On the right-hand side, ρ is rock density (in kg⋅m−3), A is elemental abundance (kg of element per kg of rock) and X is the natural isotopic fraction of the radionuclide (isotope/element), M is atomic mass (in g⋅mol−1), NA is the Avogadro constant (in mol−1), λ is decay constant (in s−1), dn(Eν)/dEν is the antineutrino intensity energy spectrum (in MeV−1, normalized to the number of antineutrinos nν produced in a decay chain when integrated over energy), and Pee(Eν,L) is the antineutrino survival probability after traveling a distance L. For an emission domain the size of the Earth, the fully oscillated energy-dependent survival probability Pee can be replaced with a simple factor ⟨Pee⟩ ≈ 0.55,[14][26] the average survival probability. Integration over the energy yields the total antineutrino flux (in cm−2⋅s−1) from a given radionuclide:

The total geoneutrino flux is the sum of contributions from all antineutrino-producing radionuclides. The geological inputs—the density and particularly the elemental abundances—carry a large uncertainty. The uncertainty of the remaining nuclear and particle physics parameters is negligible compared to the geological inputs. At present it is presumed that uranium-238 and thorium-232 each produce about the same amount of heat in the earth's mantle, and these are presently the main contributors to radiogenic heat. However, neutrino flux does not perfectly track heat from radioactive decay of primordial nuclides, because neutrinos do not carry off a constant fraction of the energy from the radiogenic decay chains of these primordial radionuclides.

Geoneutrino detection

Detection mechanism

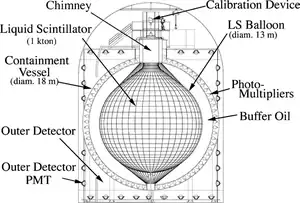

Instruments that measure geoneutrinos are large scintillation detectors. They use the inverse beta decay reaction, a method proposed by Bruno Pontecorvo that Frederick Reines and Clyde Cowan employed in their pioneering experiments in 1950s. Inverse beta decay is a charged current weak interaction, where an electron antineutrino interacts with a proton, producing a positron and a neutron:

Only antineutrinos with energies above the kinematic threshold of 1.806 MeV—the difference between rest mass energies of neutron plus positron and proton—can participate in this interaction. After depositing its kinetic energy, the positron promptly annihilates with an electron:

With a delay of few tens to few hundred microseconds the neutron combines with a proton to form a deuteron:

The two light flashes associated with the positron and the neutron are coincident in time and in space, which provides a powerful method to reject single-flash (non-antineutrino) background events in the liquid scintillator. Antineutrinos produced in man-made nuclear reactors overlap in energy range with geologically produced antineutrinos and are also counted by these detectors.[25]

Because of the kinematic threshold of this antineutrino detection method, only the highest energy geoneutrinos from 232Th and 238U decay chains can be detected. Geoneutrinos from 40K decay have energies below the threshold and cannot be detected using inverse beta decay reaction. Experimental particle physicists are developing other detection methods, which are not limited by an energy threshold (e.g., antineutrino scattering on electrons) and thus would allow detection of geoneutrinos from potassium decay.

Geoneutrino measurements are often reported in Terrestrial Neutrino Units (TNU; analogy with Solar Neutrino Units) rather than in units of flux (cm−2 s−1). TNU is specific to the inverse beta decay detection mechanism with protons. 1 TNU corresponds to 1 geoneutrino event recorded over a year-long fully efficient exposure of 1032 free protons, which is approximately the number of free protons in a 1 kiloton liquid scintillation detector. The conversion between flux units and TNU depends on the thorium to uranium abundance ratio (Th/U) of the emitter. For Th/U=4.0 (a typical value for the Earth), a flux of 1.0 × 106 cm−2 s−1 corresponds to 8.9 TNU.[14]

Detectors and results

Existing detectors

KamLAND (Kamioka Liquid Scintillator Antineutrino Detector) is a 1.0 kiloton detector located at the Kamioka Observatory in Japan. Results based on a live-time of 749 days and presented in 2005 mark the first detection of geoneutrinos. The total number of antineutrino events was 152, of which 4.5 to 54.2 were geoneutrinos. This analysis put a 60 TW upper limit on the Earth's radiogenic power from 232Th and 238U.[5]

A 2011 update of KamLAND's result used data from 2135 days of detector time and benefited from improved purity of the scintillator as well as a reduced reactor background from the 21-month-long shutdown of the Kashiwazaki-Kariwa plant after Fukushima. Of 841 candidate antineutrino events, 106 were identified as geoneutrinos using unbinned maximum likelihood analysis. It was found that 232Th and 238U together generate 20.0 TW of radiogenic power.[9]

Borexino is a 0.3 kiloton detector at Laboratori Nazionali del Gran Sasso near L'Aquila, Italy. Results published in 2010 used data collected over live-time of 537 days. Of 15 candidate events, unbinned maximum likelihood analysis identified 9.9 as geoneutrinos. The geoneutrino null hypothesis was rejected at 99.997% confidence level (4.2σ). The data also rejected a hypothesis of an active georeactor in the Earth's core with power above 3 TW at 95% C.L.[7]

A 2013 measurement of 1353 days, detected 46 'golden' anti-neutrino candidates with 14.3±4.4 identified geoneutrinos, indicating a 14.1±8.1 TNU mantle signal, setting a 95% C.L limit of 4.5 TW on geo-reactor power and found the expected reactor signals.[27] In 2015, an updated spectral analysis of geoneutrinos was presented by Borexino based on 2056 days of measurement (from December 2007 to March 2015), with 77 candidate events; of them, only 24 are identified as geonetrinos, and the rest 53 events are originated from European nuclear reactors. The analysis shows that the Earth crust contains about the same amount of U and Th as the mantle, and that the total radiogenic heat flow from these elements and their daughters is 23–36 TW.[28]

SNO+ is a 0.8 kiloton detector located at SNOLAB near Sudbury, Ontario, Canada. SNO+ uses the original SNO experiment chamber. The detector is being refurbished and is expected to operate in late 2016 or 2017.[29]

Planned and proposed detectors

- Ocean Bottom KamLAND-OBK OBK is a 50 kiloton liquid scintillation detector for deployment in the deep ocean.

- JUNO (Jiangmen Underground Neutrino Observatory, website) is a 20 kiloton liquid scintillation detector currently under construction in Southern China. The JUNO detector is scheduled to become operational in 2023.[30]

- Jinping Neutrino Experiment is a 4 kiloton liquid scintillation detector currently under construction in the China JinPing Underground Laboratory (CJPL) scheduled for completion in 2022.[31]

- LENA (Low Energy Neutrino Astronomy, website) is a proposed 50 kiloton liquid scintillation detector of the LAGUNA project. Proposed sites include Centre for Underground Physics in Pyhäsalmi (CUPP), Finland (preferred) and Laboratoire Souterrain de Modane (LSM) in Fréjus, France.[32] This project seems to be cancelled.

- at DUSEL (Deep Underground Science and Engineering Laboratory) at Homestake in Lead, South Dakota, USA[33]

- at BNO (Baksan Neutrino Observatory) in Russia[34]

- EARTH (Earth AntineutRino TomograpHy)

- Hanohano (Hawaii Anti-Neutrino Observatory) is a proposed deep-ocean transportable detector. It is the only detector designed to operate away from the Earth's continental crust and from nuclear reactors in order to increase the sensitivity to geoneutrinos from the Earth's mantle.[22]

Desired future technologies

- Directional antineutrino detection. Resolving the direction from which an antineutrino arrived would help discriminate between the crustal geoneutrino and reactor antineutrino signal (most antineutrinos arriving near horizontally) from mantle geoneutrinos (much wider range of incident dip angles).

- Detection of antineutrinos from 40K decay. Since the energy spectrum of antineutrinos from 40K decay falls entirely below the threshold energy of inverse beta decay reaction (1.8 MeV), a different detection mechanism must be exploited, such as antineutrino scattering on electrons. Measurement of the abundance of 40K within the Earth would constrain Earth's volatile element budget.[24]

References

- "Signals from Inside the Earth". Tech Explorist. 2020-01-23. Retrieved 2020-01-23.

- Cowan, C. L.; Reines, F.; Harrison, F. B.; Kruse, H. W.; McGuire, A. D. (1956). "Detection of the free neutrino: a confirmation". Science. 124 (3212): 103–662. Bibcode:1956Sci...124..103C. doi:10.1126/science.124.3212.103. PMID 17796274.

- Eder, G. (1966). "Terrestrial neutrinos". Nuclear Physics. 78 (3): 657–662. Bibcode:1966NucPh..78..657E. doi:10.1016/0029-5582(66)90903-5.

- Krauss, L. M.; Glashow, S. L.; Schramm, D. N. (1984). "Antineutrino astronomy and geophysics". Nature. 310 (5974): 191–198. Bibcode:1984Natur.310..191K. doi:10.1038/310191a0. S2CID 4235872.

- Araki, T; et al. (2005). "Experimental investigation of geologically produced antineutrinos with KamLAND". Nature. 436 (7050): 499–503. Bibcode:2005Natur.436..499A. doi:10.1038/nature03980. PMID 16049478. S2CID 4367737.

- Overbye, D. (July 28, 2005). "Baby Oil and Benzene Provide Look at Earth's Radioactivity". New York Times. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- Borexino Collaboration (2010). "Observation of geo-neutrinos". Phys. Lett. B. 687 (4–5): 299–304. arXiv:1003.0284. Bibcode:2010PhLB..687..299B. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2010.03.051.

- Edwards, L. (March 16, 2010). "Borexino experiment detects geo-neutrinos". PhysOrg.com. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- The KamLAND Collaboration (2011). "Partial radiogenic heat model for Earth revealed by geoneutrino measurements" (PDF). Nature Geoscience. 4 (9): 647–651. Bibcode:2011NatGe...4..647K. doi:10.1038/ngeo1205.

- "What Keeps Earth Cooking?". ScienceDaily. July 18, 2011. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- KamLAND Collaboration; Gando, A.; Gando, Y.; Hanakago, H.; Ikeda, H.; Inoue, K.; Ishidoshiro, K.; Ishikawa, H.; Koga, M. (2013-08-02). "Reactor on-off antineutrino measurement with KamLAND". Physical Review D. 88 (3): 033001. arXiv:1303.4667. Bibcode:2013PhRvD..88c3001G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.88.033001. S2CID 55754667.

- Bellini, G.; Benziger, J.; Bick, D.; Bonfini, G.; Bravo, D.; Buizza Avanzini, M.; Caccianiga, B.; Cadonati, L.; Calaprice, F. (2013-05-24). "Measurement of geo-neutrinos from 1353 days of Borexino". Physics Letters B. 722 (4–5): 295–300. arXiv:1303.2571. Bibcode:2013PhLB..722..295B. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2013.04.030. S2CID 55822151.

- Borexino Collaboration; Agostini, M.; Appel, S.; Bellini, G.; Benziger, J.; Bick, D.; Bonfini, G.; Bravo, D.; Caccianiga, B. (2015-08-07). "Spectroscopy of geoneutrinos from 2056 days of Borexino data". Physical Review D. 92 (3): 031101. arXiv:1506.04610. Bibcode:2015PhRvD..92c1101A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.92.031101. S2CID 55041121.

- Dye, S. T. (2012). "Geoneutrinos and the radioactive power of the Earth". Rev. Geophys. 50 (3): RG3007. arXiv:1111.6099. Bibcode:2012RvGeo..50.3007D. doi:10.1029/2012RG000400. S2CID 118667366.

- Davies, J. H.; Davies, D. R. (2010). "Earth's surface heat flux" (PDF). Solid Earth. 1 (1): 5–24. Bibcode:2010SolE....1....5D. doi:10.5194/se-1-5-2010.

- Javoy, M.; et al. (2010). "The chemical composition of the Earth: Enstatite chondrite models". Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 293 (3–4): 259–268. Bibcode:2010E&PSL.293..259J. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2010.02.033.

- Turcotte, D. L.; Schubert, G. (2002). Geodynamics, Applications of Continuum Physics to Geological Problems. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521666244.

- Palme, H.; O'Neill, H. St. C. (2003). "Cosmochemical estimates of mantle composition". Treatise on Geochemistry. 2 (ch. 2.01): 1–38. Bibcode:2003TrGeo...2....1P. doi:10.1016/B0-08-043751-6/02177-0.

- Hart, S. R.; Zindler, A. (1986). "In search of a bulk-Earth composition". Chem. Geol. 57 (3–4): 247–267. Bibcode:1986ChGeo..57..247H. doi:10.1016/0009-2541(86)90053-7.

- McDonough, W. F.; Sun, S.-s. (1995). "The composition of the Earth". Chem. Geol. 120 (3–4): 223–253. Bibcode:1995ChGeo.120..223M. doi:10.1016/0009-2541(94)00140-4.

- Huang, Y.; Chubakov, V.; Mantovani, M.; Rudnick, R. L.; McDonough, W. F. (2013). "A reference Earth model for the heat producing elements and associated geoneutrino flux". arXiv:1301.0365 [physics.geo-ph].

- Learned, J. G.; Dye, S. T.; Pakvasa, S. (2008). "Hanohano: A Deep Ocean Anti-Neutrino Detector for Unique Neutrino Physics and Geophysics Studies". Proceedings of the Twelfth International Workshop on Neutrino Telescopes, Venice, March 2007. arXiv:0810.4975. Bibcode:2008arXiv0810.4975L.

- O'Neill, H. St. C.; Palme, H. (2008). "Collisional erosion and the non-chondritic composition of the terrestrial planets". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. A. 366 (1883): 4205–4238. Bibcode:2008RSPTA.366.4205O. doi:10.1098/rsta.2008.0111. PMID 18826927. S2CID 14526775.

- Bellini, G.; Ianni, A.; Ludhova, L.; Mantovani, F.; McDonough, W. F. (2013-11-01). "Geo-neutrinos". Progress in Particle and Nuclear Physics. 73: 1–34. arXiv:1310.3732. Bibcode:2013PrPNP..73....1B. doi:10.1016/j.ppnp.2013.07.001. S2CID 237116200.

- Usman, S.; et al. (2015). "AGM2015: Antineutrino Global Map". Scientific Reports. 5: 13945. arXiv:1509.03898. Bibcode:2015NatSR...513945U. doi:10.1038/srep13945. PMC 4555106. PMID 26323507.

- Fiorentini, G; Fogli, G. L.; Lisi, E.; Mantovani, F.; Rotunno, A. M. (2012). "Mantle geoneutrinos in KamLAND and Borexino". Phys. Rev. D. 86 (3): 033004. arXiv:1204.1923. Bibcode:2012PhRvD..86c3004F. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.86.033004. S2CID 118437963.

- Borexino Collaboration (24 May 2013). "Measurement of geo-neutrinos from 1353 days of Borexino". Physics Letters B. 722 (4–5): 295–300. arXiv:1303.2571. Bibcode:2013PhLB..722..295B. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2013.04.030. S2CID 55822151.

- Borexino Collaboration (7 August 2015). "Spectroscopy of geoneutrinos from 2056 days of Borexino data". Phys. Rev. D. 92 (3): 031101. arXiv:1506.04610. Bibcode:2015PhRvD..92c1101A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.92.031101. S2CID 55041121.

- Andringa, S.; et al. (SNO+ Collaboration) (2015-11-13). "Current Status and Future Prospects of the SNO+ Experiment". Advances in High Energy Physics. 2016: 6194250. arXiv:1508.05759. doi:10.1155/2016/6194250. S2CID 10721441.

- JUNO website, 2022-07-23

- Beacom, John F.; Chen, Shaomin; Cheng, Jianping; Doustimotlagh, Sayed N.; Gao, Yuanning; Ge, Shao-Feng; Gong, Guanghua; Gong, Hui; Guo, Lei (2016-02-04). "Letter of Intent: Jinping Neutrino Experiment". Chinese Physics C. 41 (2): 023002. arXiv:1602.01733. Bibcode:2017ChPhC..41b3002B. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/41/2/023002. S2CID 197514524.

- Wurm, M.; et al. (2012). "The next-generation liquid-scintillator neutrino observatory LENA". Astroparticle Physics. 35 (11): 685–732. arXiv:1104.5620. Bibcode:2012APh....35..685W. doi:10.1016/j.astropartphys.2012.02.011. S2CID 118456549.

- Tolich, N.; et al. (2006). "A Geoneutrino Experiment at Homestake". Earth, Moon, and Planets. 99 (1): 229–240. arXiv:physics/0607230. Bibcode:2006EM&P...99..229T. doi:10.1007/s11038-006-9112-8. S2CID 54889933.

- Barabanov, I. R.; Novikova, G. Ya.; Sinev, V. V.; Yanovich, E. A. (2009). "Research of the natural neutrino fluxes by use of large volume scintillation detector at Baksan". arXiv:0908.1466 [hep-ph].

Further reading

- Dye, S. T., ed. (2007). Neutrino Geophysics: Proceedings of Neutrino Sciences 2005. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-70771-6. ISBN 978-0-387-70766-2.

- McDonough, W. F.; Learned, J. G.; Dye, S. T. (2012). "The many uses of electron antineutrinos". Phys. Today. 65 (3): 46–51. Bibcode:2012PhT....65c..46M. doi:10.1063/PT.3.1477.

External links

- Deep Ocean Neutrino Sciences describes deep ocean geo-neutrino detection projects with references and links to workshops.

- Neutrino Geoscience 2015 Conference provides presentations by experts covering almost all areas of geoneutrino science. Site also contains links to previous "Neutrino Geoscience" meetings.

- Geoneutrinos.org is an interactive website allowing you to view the geoneutrino spectra anywhere on Earth (see "Reactors" tab) and manipulate global geoneutrino models (see "Model" tab)