George Chakravarthi

George Chakravarthi is a multi-disciplinary artist working with photography, video, painting and performance. His work addresses the politics of identity including race, sexuality and gender, and also religious iconography among other subjects. He was born in India and moved to London, England in 1980.[1]

George Chakravarthi | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Born | 26 November 1969 New Delhi, India |

| Nationality | British (formerly Indian) |

| Occupation | Artist |

| Years active | 1998 to present |

| Website | www.georgechakravarthi.com |

He has exhibited and performed all over the UK and internationally at venues including Site Gallery, Sheffield, England; Tate Modern, London, England; Victoria and Albert Museum, London, England; Künstlerhaus Mousonturm, Frankfurt, Germany; Dance Academy (Tilburg), Tilburg, Netherlands; Queens Gallery, British Council, New Delhi, India;[1] La Casa Encendida, Madrid, Spain;[2] Brut Künstlerhaus, Vienna, Austria;[3] Abrons Arts Center, New York City, USA;[4] and City Art Gallery, Ljubljana, Slovenia.[5]

Chakravarthi has been commissioned by the BBC, Artangel, Duckie, InIVA, the Arts Council of England, the British Council, the SPILL Festival of Performance, the Live Art Development Agency, the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust and the Royal Shakespeare Company.[6]

Chakravarthi studied at the University of Brighton, the Royal Academy of Arts and the Royal College of Art.[7]

Early life

Chakravarthi was born in New Delhi, India on 26 November 1969 to parents with origins in Tamil Nadu, India and British Burma. His parents considered the education of their children a priority, so the family lived very modestly in order for him and his siblings to be privately educated while in India. Chakravarthi attended St. Columba's School, Delhi,[8] an English-medium school run by a Roman Catholic brotherhood (Congregation of Christian Brothers). Although nominally brought up as a Catholic, Chakravarthi's family encouraged him to absorb and be influenced by Hinduism and Buddhism.[9][10]

In 1980, Chakravarthi moved with his family to the UK.[11] This was around the time of the Brixton and other riots,[12] and the peaks for organised racism and electoral success of the far-right (National Front General election results in May 1979). Mary Brennan, reviewing the National Review of Live Art in 2001, described the effect on Chakravarthi of his move to the UK as follows:

[He] entered into a kind of mirror-maze, where he found himself searching for a sense of who he was. In time, that quest for identity has embraced issues of iconography, sexuality, race, and gender – all framed, as it were, within a personal reconstruction of familiar fine art.

— Mary Brennan[13]

He continued his education at St. Patrick's Primary School[14] and St. Paul's Secondary School in south London, both Roman Catholic, multi-cultural schools. He began documenting his reactions to his new environment and his changing identity through writing and drawing, and then making photographic self-portraits (initially using photo booths[15][11] until he was given a camera by the sculptor and photographer Hamish Horsley[16]).

Chakravarthi left home at the age of 16 and eventually settled in a modest flat in Greenwich, London. He had a variety of jobs including stacking shelves in supermarkets, as a go-go dancer in various nightclubs and as a photographic and artist's model. He attended a short course in photography at the Thames Independent Photography Project (TIPP) where his interest in photography and particularly making self-portraits was encouraged.[17]

Formal training

'Resurrection' by Chakravarthi

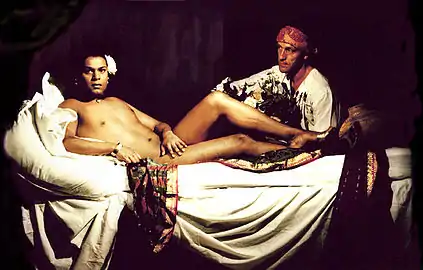

'Resurrection' by Chakravarthi 'Olympia' by Chakravarthi

'Olympia' by Chakravarthi

Chakravarthi was an undergraduate at the University of Brighton. He obtained a first-class Bachelor of Arts in Visual and Performance Art. For the degree show he submitted ′Resurrection′ (a photograph 12 feet by 5 feet) and a live performance, the subject of both was The Last Supper, with Chakravarthi in the place of Jesus and women dressed in saris in the positions of the disciples, as depicted by Leonardo da Vinci.[18] He received an award from Nagoya University for outstanding artistic achievement.

He started his postgraduate studies at the Royal Academy of Arts and,[19] after taking a year out, he completed his Master of Arts at the Royal College of Art in 2003. For the final show at the Royal College of Art, he submitted ′Olympia′, a video installation based on the painting by Édouard Manet, with Chakravarthi in the position of the nude woman and a white man in the place of the black servant woman;[20] it won him the Chris Garnham Award for 'Best Use of Photography'.

Career

'Barflies' by Chakravarthi

'Barflies' by Chakravarthi 'Thirteen' by Chakravarthi

'Thirteen' by Chakravarthi

| Name of work/ Type | Date/ Commission | Exhibitions or performances | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Remotecontrol (Video installation) | 1997 |

| Chakravarthi as an androgynous person inspired by fashion photography and the politics of an 'ideal body'. | |

| Memorabilia/Aradhana (Video installation) | 1998 |

| An homage to Bollywood cinema. Chakravarthi plays both characters and it reflects the typical style and content of popular Indian cinema of the 1980s. However, the subtitles confront sexist assumptions and patriarchy. | |

| Genesis (Video installation) | 1998 | Filmed in real-time, Chakravarthi reveals a series of emotions from happiness to extreme sadness.

| ||

| Introjection (Video installation) | 1998 |

| ||

| Resurrection (Live performance) | 1998 |

| Chakravarthi, with a shaved head and naked, takes the position of Jesus in the Last Supper tableau as painted by Leonardo da Vinci, and he is accompanied by twelve female disciples wearing saris. Hair is strewn over the table. | |

| Resurrection (Photographic) | 1998 |

| Still image of posed version of the live performance above. | |

| Shakti (Video installation) | 2000 | Chakravarthi as an hybrid combination of Mona Lisa and the Indian goddess Kali with a landscape of naked women in the background. | ||

| Barflies (Triptych video installation) | 2002 |

| Chakravarthi as three specific types of transgender women filmed in bars with a soundtrack of conversations on a telephone chat line between the artist and other transvestites and those that seek them.

| |

| Great Expectations (Live performance with video) | 2002 |

| Chakravarthi sitting with his back to the audience in front of a video projection also showing the back of his head. | |

| Olympia (Video installation) | 2003 |

|

| |

| To the Man in my Dreams (Installation and live performance) | 2006 |

| A collaborative project with members of SW5, a London advice and information service for male, female and transgender sex workers (now known as SWISH). A collection of letters between someone who calls himself 'father' and 'George'. | |

| Masking (Film) | 2009 |

Not applicable

| Short film produced to celebrate LADA's tenth anniversary.

| |

| I Feel Love! (Durational live performance) | 2009 |

| An outdoor performance lasting all day that examines ways in which the body is traditionally portrayed in public sculpture, memorials and popular culture. | |

| Ode to a Dark Star (Video installation) | 2009 |

| Chakravarthi in costume as both Shakespeare and the 3rd Earl of Southampton in a looped video displayed in a frame, giving the impression of a painting with some motion. The Cobbe portrait of Shakespeare was shown for the first time in the same exhibition (Shakespeare Found: a Life Portrait). There is also a Cobbe portrait of Southampton. | |

| George Chakravarthi UnSeen (DVD) | 2009 Live Art Development Agency | Not applicable | A slide-show of early, photographic self-portraits by Chakravarthi. The photographs show him experimenting with his identity; they represent the earliest documentation of the experiences which inform much of his current work. The soundtrack is a conversation between Chakravarthi and Andrew Mitchelson in which Chakravarthi talks about his childhood experiences in India and London, and about feeling an outsider as far as both cultures are concerned.[15] | |

| Negrophilia (Live performance) | 2010 Duckie |

| Negrophilia is inspired by the Parisian avant-garde culture of the 1920s and its fascination with Africanism (Negrophilia), Hollywood cinema's negative portrayals of Africa and Africans in the same era and the performer Josephine Baker. Chakravarthi reveals himself dressed, as Baker famously did, in a banana skirt and pearls.[51]

| |

| Thirteen (Photographic – comprises 13 separate images) | 2011 | Self-portraits of Chakravarthi in costume as thirteen Shakespeare characters (male and female) who committed suicide. Each image is layered with textures including cobwebs, mould, stone, water and clouds. Backlit transparencies in light boxes, characters about life-size.[80][81][11]

| ||

| Miss UK (an archive) (Live performance in three parts) | 2011 Duckie |

| A dance floor posing piece that celebrates the glamour and absurdity of beauty contests in the UK from the 1960s to the 90s (such as Miss United Kingdom). | |

| Andhaka (Live performance) | 2013 Live Art Development Agency | A one-to-one durational performance. Chakravarthi is present in darkness and is finally revealed in a flood of light as Kali, the Hindu goddess of destruction and creation.[86]

| ||

| Barflies (Photographic) | 2014 | Not applicable | Edition of fifteen, signed sets of three prints based on the 2002 video installation Barflies (see above). Produced for the Live Art Development Agency's 15th Anniversary Limited Editions series.[87] | |

| The Ambidextrous Universe (Photographic) | 2015 |

|

Six self-portraits, which are the first pieces of work emerging from Chakravarthi's current and ongoing research known as The Ambidextrous Universe.[88] The images explore symmetry and emphasise the fractal construction of objects in nature and religious architecture.[89][90] | |

| Border Force - I Did ′India′ (Performance installation) | 2015 Duckie |

| Performance installation as part of a Duckie 'geo-political-immersive-disko' confronting xenophobia and promoting freedom of movement.[94][95]

| |

| Let Them Eat Cake (Performance installation) |

2016 Duckie |

|

Performance installation as part of Duckie's 'Lady Malcolm's Servants' Ball'. Chakravarthi, as Marie Antoinette, hand feeds slices of a cake decorated with a map of the British Empire to members of the audience - referencing feasts and famines across the British Empire. | |

| Negrophilia (Film screening) | 2016 | |||

| Mata Bahucharaji (Goddess of Eunuchs) (Painting) |

2016 | |||

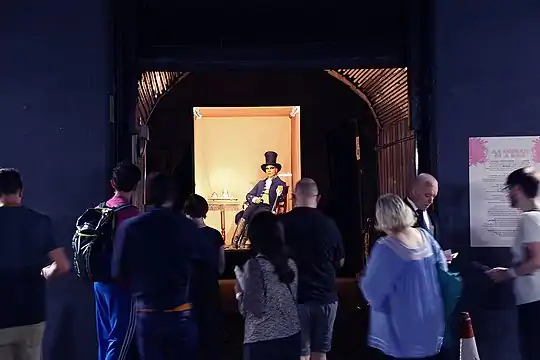

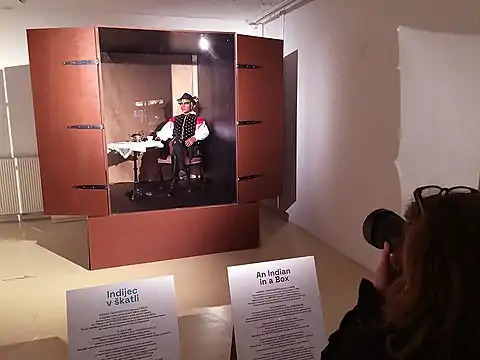

| An Indian in a Box (Performance installation) |

2021 Duckie |

|

Live, durational performance installation as part of Duckie's 'Princess: The Promenade Performance', inspired by the queer history of Georgian London. Chakravarthi presents issues of enslavement, voyeurism, fetishisation and isolation as experienced by the victims of Human Zoos, also known as Ethnological Expositions - a shameful practice that endured during the colonial era, which continued into the 1950s, and as late as the 1990s in some countries across Europe. Captured and encased in a glass cabinet, Chakravarthi, in Georgian gentleman's attire, presents himself as a living object of curiosity and an exoticised creature.

The performance in Slovenia was part of the 'International Festival of Contemporary Arts – City of Women', Chakravarthi was dressed in Slovene national costume. |

|

| AUM (Site-specific, multi-media project - video, sound and photography ) |

2022 Nomad Projects |

|

New body of work exploring Indian spiritual and tribal practices instigated while being the artist in residence at Phytology throughout 2022. See the image below of the billboard launching the work. | |

| The Ascension of the Bearded Lady (Performance installation) |

2023 Duckie |

|

Live, durational performance installation as part of the 'Duckie Summer Fete'. |

'An Indian in a Box' London performance

'An Indian in a Box' London performance 'An Indian in a Box' Ljubljana performance

'An Indian in a Box' Ljubljana performance Billboard launching 'AUM' by Chakravarthi

Billboard launching 'AUM' by Chakravarthi

In 2003 Chakravarthi was involved in the Live Art Development Agency's "Live Culture" event[109] at Tate Modern, contributing to Guillermo Gómez-Peña's collaboration[110]

Publications

- A survey of Chakravarthi's work can be found in "Sexuality (Whitechapel: Documents of Contemporary Art)" Edited by Amelia Jones, 2014.[30]

- "What do relationships mean to you? - Emotional Learning Cards" - image of Barflies used to represent gender identity.[111]

- "Performance Research - On Trans/Performance" - image of UNTITLED05, The Ambidextrous Universe used for cover.[112]

- "Agency - a partial history of live art" - conversation between Chakravarthi and Manuel Vason, and image of Negrophilia.[113]

- A still image from Chakravarthi's Olympia appears in "Rebels, radicals and revolutionaries: art and social change" by Marie-Anne Leonard [114]

Themes

A number of common themes are apparent in Chakravarthi’s work including:

- Self-portraiture: Many of Chakravarthi's works are various forms of self-portrait.

- Identity: Chakravarthi adopts numerous alter egos with different identities in his work; for example, he is male in some of the pieces within ‘Thirteen’, female for one of the characters in ‘Memorabilia/Aradhana’, transgender in ‘Barflies’, gay in ‘I Feel Love!’ and Indian in ‘Andhaka’.

- Race/multi-culturalism/racism: Jesus in ‘Resurrection’ is Indian and his hair, scattered over the table, is black in contrast to the (apparently) red hair of the white Jesus in Da Vinci's The Last Supper, and the female disciples are all dressed in traditional Indian saris reflecting Chakravarthi's cultural heritage (see the image of this work above). In ‘Olympia’ the servant is white and the “mistress” is Indian (see the image of this work above). ‘Negrophilia’ takes on the dichotomy between the fascination of some white audiences with black performers, e.g. Josephine Baker in Paris, and racist imagery in Hollywood cinema of the same era, e.g. the number ′Hot Voodoo′ in Blonde Venus, 1932 (Chakravarthi appears on stage in a gorilla costume), and subtly refers to evolution (ape to homo sapiens, and the origin of homo sapiens in the African continent).

- Gender/sexism/feminism: The female character in ‘Memorabilia/Aradhana’ is cast as a person to be married off and produce children for her husband. The twelve apostles in ‘Resurrection’ are all female, possibly alluding to the women apostles referred to in non-canonical Christian texts and in the Bible in Romans 16:7 (female disciples of Jesus). ‘Miss UK’, ‘Masking’ and ‘Barflies’ in particular address feminist politics.

- Sexuality/transvestitism: Chakravarthi dresses as female characters in many of his pieces of work, these include; ‘Memorabilia/Aradhana’, ‘Shakti’, ‘Barflies’, ‘Negrophilia’, some of the pieces within ‘Thirteen’, ‘Miss UK’ and ‘Andhaka’. In others (‘Remotecontrol’ and ‘Olympia’) the characters are androgynous. ‘To the Man in my Dreams’ can be interpreted as a son coming out to his father, or the correspondence between a gay man in a role-play relationship with an older man, among other possibilities. Chakravarthi’s character in ‘I Feel Love!’ (in terms of dress, the music used and his placement on a plinth) is probably based on a go-go dancer in a gay club.

- Self image/idealisation of image: ‘Remotecontrol’, ‘I Feel Love!’, ‘Barflies’ and ‘Miss UK’ all concern themselves with striving to have the ‘right’ image whether in terms of body, dress or age.

- Religion: ‘Shakti’ and ‘Andhaka’ explicitly refer to the Indian goddess Kali, and the Last Supper from the Bible is the subject of ‘Resurrection’. The layering of the components within the images of ‘Thirteen’ gives them an appearance of stained glass, particularly when displayed backlit in light boxes (see the photograph above of some of these images backlit in an exhibition), this may be a more subtle religious reference.

- Iconic paintings: A number of iconic paintings are specifically and unmistakably referenced by some of Chakravarthi's pieces, with details of the sets as well as the main subjects; Da Vinci's Mona Lisa in ‘Shakti’ and also his The Last Supper in ‘Resurrection’, and Manet's Olympia in ‘Olympia’. The use of gold and jewels in Cleopatra (within ‘Thirteen’) is reminiscent of works by Klimt (e.g. Adele Bloch-Bauer, 1907). Numerous paintings by Titian (e.g. Equestrian Portrait of Charles V, 1548) make dramatic use of clouds as does Chakravarthi's Lady Macbeth (also within ‘Thirteen’) – see the third image from the right in the photograph above of some of the images from ‘Thirteen’.

Personal life

Chakravarthi is married and lives in London and Leicestershire. He and his husband have been together since January 1994, they were legally married at Chelsea Old Town Hall, King's Road, London in May 2006 (their civil partnership having later been converted into marriage).[115]

See also

- Chakraborty - meaning of the name Chakravarthi.

References

- "About George Chakravarthi". Artangel. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- "Cita con la danza más rara - Elena Córdoba actúa en Madrid y coincide con el ciclo In-Presentable". El Cultural.

- "Negrophilia". Duckie. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- "Just Like A Woman". Abrons Arts Center. Abrons Arts Center. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- "An Indian in a Box". City of Women. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- "George Chakravarthi". University of Brighton. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- "George Chakravarthi – Artist". InIVA. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- "St. Columba's School, Delhi website". St. Columba's School, Delhi. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- "George Chakravarthi – Bio". George Chakravarthi. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- Millican, Nikki. "Being, not performing". Brisbane Powerhouse Centre for the Live Arts. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- Keegan, Sinead (18 May 2017). "The dislocated artist". All the sins. All the sins. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- "1981: Brixton riots report blames racial tension". BBC. 25 November 1981. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- Brennan, Mary. "Join in the Mexican wave The events of five packed days of the National Review of Live Art are previewed". Herald Scotland. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- "St Patrick's Catholic Primary School, Plumstead".

- "unSeen". Live Art Development Agency. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- Horsley, Hamish. "Hamish Horsley". Hamish Horsley. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- "Shooting Live". BBC. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- "Resurrection". George Chakravarthi. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- "George Chakravarthi | Artist | Royal Academy of Arts". Royal Academy.

- "Olympia by George Chakravarthi". Youtube/George Chakravarthi. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- "Site Gallery George Chakravarthi Exhibition". Site Gallery. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- "Chakravarthi at Sketch". In the Spirit. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- "Big M". ISIS Arts. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- "Free To Air". Free To Air. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- "George Chakravarthi – Genesis". Fine Art Visiting Speaker Forum. 15 March 2009. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- "George Chakravarthi – Introjection Video". George Chakravarthi. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- Perappadan, Bindu Shajan (20 April 2004). "Exploration of the 'self'". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 8 February 2015. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- "Site Gallery – Shakti". Site Gallery. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- Jackson, Tina (June 2007). "Five questions for... George Chakravarthi". Metro. Metro.

- Jones, Amelia (August 2014). Sexuality. The MIT Press. ISBN 9780262526579.

- Hickling, Alfred (August 2002). "George Chakravarthi". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- "Encuentro con George Chakravarthi". Fundacion Montemadrid.

- Öman, Ann-Sofie. "Ann-Sofie Öman on Barflies by George Chakravarthi". City of Women/Danstidningen. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- "Barflies". City of Women. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- "LADA Screens". Live Art Development Agency. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- "LADA Screens: George Chakravarthi". this is tomorrow - Contemporary Art Magazine. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- "LADA Summer Programme 2020: George Chakravarthi". LADA. Live Art Development Agency.

- "Kunstbanken". Kunstbanken Hedmark Kunstsenter. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- "Olympia". Scene Web. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- "Big Screen, Cornerhouse, Manchester". Cornerhouse, Manchester. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- "Artangel To the Man in my Dreams". Artangel. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- "Tenth Anniversary Short Films – George Chakravarthi". Live Art Development Agency. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- "I Feel Love". Spill Festival. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- Clapham, Rachel Lois (April 2009). "Elevated Exhibitionism". Open Dialogues. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- Toms, Katie (9 December 2007). "The present doctor will see you now". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- "Shakespeare's Birthday Events". British Theatre Guide. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- "ALAG". Live Art Development Agency. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- Paterson, Mary (27 January 2015). "Live art performers take a hammer to arts funding debate". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- "Brut-Wein". Brut Wein. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- "Just Like A Woman: NYC Edition Programme". LADA. LADA. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

- "Negrophilia". Abrons Arts Center. Abrons Arts Center. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- "Not Just the Wild, Crazy Queer Stuff at Abrons's Just Like a Woman Festival". American Theatre. Theatre Communications Group. 16 October 2015. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- Keidan, Lois (22 October 2015). "Live Art: the research lab for mass culture". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- "Just Like A Woman: London Edition Programme". LADA. LADA. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

- "PERFORMANCES/SACRED: Gender Spectacle Cabaret". Chelsea Theatre. Chelsea Theatre. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- "Twenty First Century Music Hall". Duckie. Duckie. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- "Duckie: 21st Century Music Hall". Heart of Glass. Heart of Glass.

- "Duckie presents 21st Century Music Hall – Preview: Duckie hits St. Helens for Homotopia". Vada magazine. Vada magazine. 10 November 2015.

- "Duckie Competition for Through the Looking Glass". LADA. LADA. 5 November 2015.

- Paterson, Mary. "A Live Art Gala" (PDF). LADA. LADA. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- "Thirteen at RSC". Royal Shakespeare Company. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- "Shakespeare and suicide: George Chakravarthi's Thirteen". The Shakespeare Blog. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- Clark, Robert (22 March 2014). "Art – this week's new exhibitions – 22 Mar 2014". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- "Thirteen at Impressions Gallery". Impressions Gallery. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- "Bard's doomed characters are brought to life at Bradford gallery". Bradford Telegraph & Argus.

- "Dark side of Shakespeare". Bradford Telegraph & Argus.

- "Aesthetica Magazine Review". Aesthetica Magazine. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- "F-Stop Magazine Review". F-Stop Magazine. 7 February 2014. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- "The Indian Quarterly review of Thirteen". The Indian Quarterly. 2 (3). April 2014.

- "Death, Drama And Identity: Thirteen Exhibition". Yorkshire Times. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- "George Chakravarthi: Thirteen". Bradford Festival. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- Hamid, Shaila (4 June 2014). "Review by Shaila Hamid 'Feed Your Mind' at Impressions Gallery George Chakravarthi, 'Thirteen'". New Focus/Impressions Gallery. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- "Vane Gallery – Thirteen". Vane Gallery. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- "Globe Gallery – Thirteen". Globe Gallery. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- "NOW SHOWING #84: The week's top exhibitions". a-n The Artists Information Company.

- "George Chakravarthi: Thirteen". The List. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- Stevens, Ben. "Newcastle upon Tyne: George Chakravarthi: Thirteen". England Events. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- "Art News – George Chakravarthi: Thirteen, Vane". Arts Council England. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- Whetstone, David (19 March 2015). "Popular Globe Gallery set to reopen in new city centre location". The Journal. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- "04. Royal Shakespeare Exhibition – Artwork by George Chakravarthi". Lite House Europe Ltd. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- "Metro Supports George Chakravarthi – Thirteen". Metro Imaging. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- "Miss UK". South Bank Centre. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- "Tonight! Duckie turns Sweet 16". Gay Times. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- "Andhaka in Ljubljana". WherEvent. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- "George Chakravarthi – Andhaka". City of Women. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- Gluzman, Yelena; Yankelevich, Matvei, eds. (2014). Emergency Index – an annual document of performance practice – Vol 3. The Bros. Lumiere for Ugly Duckling Press. pp. 506–507. ISBN 978-1-937027-50-6.

- "Barflies prints". Live Art Development Agency. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- "The Ambidextrous Universe – Research". Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- "The Ambidextrous Universe". George Chakravarthi. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- "Photography". George Chakravarthi. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- "Border Force". Duckie. Retrieved 16 June 2015.

- "Border Force (London)". George Chakravarthi. Retrieved 16 June 2015.

- "Border Force (Brighton)". George Chakravarthi. Retrieved 16 June 2015.

- "Border Talk (recording of the panel event held prior to the first Border Force event)". Duckie.

- "Border Force". Joshua Sofaer. Retrieved 16 June 2015.

- "Lady Malcolm's Servants' Ball". Duckie. Duckie. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- "Duckie: Lady Malcolm's Servants' Ball". Live Art UK. Live Art UK. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- "Just Like a Woman". livecollision. 8 November 2016. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- "IBT17". IBT17. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- Stonewall Season - Closing Celebration (catalogue of auctioned artwork). Stonewall. 2016. p. 22.

- "Princess: The Promenade Performance". Duckie. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- "An Indian in a Box". George Chakravarthi. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- "Princess Picnic Promenade". Duckie. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- "Healing Gardens of Bab: Princess, Picnic, Promenade". Birmingham 2022 Festival.

- "Duckie (London) Princess, Picnic, Promenade". Fierce Festival.

- "George Chakravarthi at Phytology". Phytology. Phytology. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- "George Chakravarthi AUM". Bethnal Green Nature Reserve. Bethnal Green Nature Reserve. Retrieved 18 June 2023.

- "Duckie Summer Fete". Duckie. Retrieved 18 June 2023.

- "Live Culture at Tate Modern". Live Art Development Agency. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- "Masterclass with Guillermo Gomez-Pena". Live Art Development Agency. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- What do relationships mean to you?. Space, iniva, Arts Council England. November 2016. ISBN 978-1-899846-59-7.

- Jones, Amelia, ed. (October 2016). "On Trans/Performance". Performance Research. Routledge. 21 (5): Cover. ISSN 1352-8165.

- Schmidt, Theron, ed. (2019). Agency - a partial history of live art. Live Art Development Agency. pp. 29–38. ISBN 978-1-78320-990-3.

- Marie-Anne Leonard (December 2020). "Rebels, radicals and revolutionaries: art and social change". Canon Europe. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- "General Register Office". GRO.

External links

- Official website

- Show-reel of selected works of Chakravarthi 1997 - 2015 on YouTube

- Chakravarthi videos on YouTube

- Chakravarthi interview at Impressions Gallery, Bradford 12 April 2014 (audio)

- Chakravarthi interview by Adelaida Afilipoaie April 2014 (audio) for Ramair, Bradford University Student Radio

- Making the Cut – George Chakravarthi and Campbell, in conversation with InIVA curator Grant Watson (with links to audio recording and photographs), 2010