George Phillpotts

Lieutenant George Phillpotts (1814 – 1 July 1845) was an officer of the Royal Navy. He was born in Durham, England in or about 1814.[10]

George Phillpotts | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Memorial to George Phillpotts in St James' Church, Sydney | |

| Nickname(s) | Toby or Topi (Māori),[1] Matua Keke (Māori) and Uncle Toby[2] |

| Born | 1813 or January 1814 Durham, England |

| Died | 1 July 1845 Ōhaeawai, New Zealand |

| Buried | St John the Baptist Church Cemetery, Waimate North, Northland, New Zealand[3] |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | |

| Years of service | 1827–1845 |

| Rank | Lieutenant[4] |

| Unit | HMS Hazard[4] |

| Commands held | HMS Hazard (acting) |

| Campaigns | China Flagstaff War |

| Memorials | St Michael's Church, Ōhaeawai, Northland (roll of honour)[7] St James' Church, King Street, Sydney, New South Wales (memorial tablet)[8] St Budock Parish Church, Budock Water, Cornwall (memorial stained glass window)[9] |

| Relations | Henry Phillpotts (father) John Phillpotts (uncle) George Phillpotts, RE (uncle) William Phillpotts (brother) |

Career

George Phillpotts entered the Royal Navy on 5 September 1827,[11] advanced to mate through examination on 26 November 1833, served on HMS Asia.[12]: 157 However, in January 1841, General William Dyott, 63rd Regiment,[13] observed that he'd left the navy and was helping his friend Dick Dyott, the General's son, and the Conservative Party:

"On the 6th a friend of Dick's, Mr. Phillpotts, a son of the Bishop of Exeter's, came for two nights, and was an able help in assisting at our party the following day. He had been in the navy, but on account of his father's politicks could not obtain promotion and quitted, and was employing himself in a colliery and in iron works at Dudley. Dick made acquaintance with him at Plymouth when he was serving as midshipman. He is a nice gentlemanlike youngster.[14]

Phillpotts received his commission in the Royal Navy with rank of lieutenant on 12 November 1841.[4]: 72, 302 On 8 February 1842 he was appointed to the newly commissioned HM Steam Sloop Vixen, under Commander Henry Boyes, RN,[15]: 76 being manned and provisioned at Plymouth, England, for her maiden voyage to the East India station and China.

China

Vixen, as part of long expected reinforcements from England and India for the First Anglo-Chinese War, HMS Hazard amongst them, joined the British fleet at anchor off Chapoo, China, in May 1842,[16]: 149–150 Then whilst off Woosung following the capture of the town, Vixen was placed in company with HM Ships Cornwallis, Calliope, transport Marion with Sir Hugh Gough and staff, and seven other transports in the first of the six divisions of the General Squadron, for the cruise up the Yangtze River on 6 July to Nanking. She took Cornwallis in tow up to Kin Shan (Golden Island). In the afternoon of 15 July, Gough and Sir William Parker went on in the Vixen to reconnoitre Kin Shan and the approaches to Chinkiang at the entrance of the South Grand Canal.[16]: 154–155 [17] Vixen's officers and sailors assisted in the storming and capture of Chinkiang on 21 July 1842.[17]

Having passed Kin Shan, Vixen came alongside the flagship HMS Cornwallis on 3 August and took her in tow up the river to anchor off the batteries at Nanking. She stood in the river with HM ships Cornwallis, Blonde, Modeste, Childers, Clio, Driver, and HEIC steamers Auckland, Queen, Pluto, Phlegathon and Medussa during the treaty negotiations that bought an end to the war.[18][19]

For their participation, Vixen's crew were eligible for the China War Medal (1842).[20]

New South Wales

Lieutenant Phillpotts was appointed to HMS Hazard, under Commander Charles Bell, RN,[4]: 226 on 15 December 1842, the day of her arrival at Sydney, New South Wales. After China, Hazard had left Singapore on 18 October, Anyer, Indonesia on 1 November, for refitting in Sydney into January 1843.[21]

South Sea cruises

On 25 January Hazard departed Sydney for Tahiti, following HMS Vindictive, which had sailed several days before carrying the British Consul, George Pritchard, to that place. In case of hostilities, Commander Bell was to report to the Admiral of the South American Station for further instructions.[22] Subsequent to visiting Tahiti, Hazard was to cruise the South Seas in search of the whaler Water Witch, which had been carried off by its mate.[23] They arrived back in Sydney on 24 March.[24]

HMS Hazard left Sydney for Hobart on 11 or 12 April 1843,[25] then headed to Tahiti a few days after its arrival.[26]

Whilst at Oʻahu, Hawaii, Hazard went to San Blas, Mexico, in January 1844, to bring William Miller, Consul General of the Sandwich Islands and the Pacific, and suite, to Hawaii. Thereafter they left Honolulu, Oʻahu, for Lahaina, Maui, on 8 February, for presentation to the King of Hawaii, Kamehameha III on 10 February and signing of the Convention Between Great Britain and the Sandwich Islands on 12 February.[27][28][29] Hazard then sailed for Mazatlán, Mexico, seemingly returning to Hawaii and Tahiti in March.

After the departure of the Shamrock on 8 March, a serious skirmish took place between the Tahitians and French, commencing the Franco-Tahitian War. The Tahitians, assisted by the American and European seamen on the Island, managed to take six field pieces from the French, and kill about eighty. A gunner, formerly of HMS Vindictive, was at the head of the Tahitians.[30]

Captain Bell, of H.M.S. Hazard, on his arrival at Tahiti, sent a boat ashore in command of an officer, which, on reaching, was at once seized by the French guard stationed on Papiete beach, and the officer and his crew were taken prisoners. After a detention, however, of several hours, they were 'sent off' to their ship, with the understanding that 'the subjects of Great Britain could not on any account be allowed to land on that Island,' as the French Governor declared the Island 'to be in a state of siege.' This declaration, on the part of the French Governor, is really too Quixotic to be viewed in any other light than that of pity—the act of besieging an unfortified place, must be brave indeed![31]

HMS Hazard touched at Tutuila, Samoan Islands in late April,[32] and arrived back in Sydney on 18 May 1844, having traversed at least a distance of 30,000 miles on that cruise. The ship and crew departed Sydney, New South Wales, for Auckland, New Zealand on 4 July 1844.[33]

New Zealand

HMS Hazard, under the command of Acting Commander David Robertson-Macdonald[5][34][35] following Commander Bell's death in August 1844, was in the Bay of Islands, New Zealand at the start of the Flagstaff War.

Kororāreka

At dawn on Tuesday 11 March 1845, a force of about 600 Māori armed with muskets, double-barrelled guns and tomahawks commenced the Battle of Kororāreka.[36]: 11–15, 76–84

Lieutenant Phillpotts, in command of HMS Hazard after Commander Robertson-Macdonald was severely wounded,[5] ordered the bombardment of Kororāreka.[37] In the early hours of Thursday, 13 March, the third day on, HMS Hazard prepared for sea and conveyed the sick and wounded to Auckland.[37]

In review of the battle's sequence of unfortunate events on 11 March 1845, Phillpotts reported to Governor FitzRoy on 15 March:

…but the conclusion I have come to is, that had possession of the blockhouse at the flagstaff, in charge of Ensign Campbell, been retained, I should not now be suffering from the feelings naturally occurring to a man who has been subdued.

That it was a defeat I must acknowledge, as I consider losing the flag-staff in the same light as losing a ship.[38]

Waikare

On the night of 15 May 1845, a week after the battle of Puketutu, Major Cyprian Bridge, 58th Regiment, with 200 men of the regiment, 8 marines and a 12-pounder carronade, worked their way up the Waikare river in boats, each with an armed seaman from HMS Hazard, to attempt a surprise attack on the Kapotai pā. Near daybreak, disorientation and tidal groundings had only delivered Bridge, now before the pā, a force of 50 troops and 100 of Tāmati Wāka Nene's warriors. Firing from the pa commenced at daybreak but its inhabitants, wary of the attack, soon moved to abandon it. Nene's warriors supported with company of the 58th fought Kapotai warriors, reinforced by a party of Kawiti's men, in the bush around the pā for some six or seven hours. During the operation, Phillpotts captured two boats, and Bridge allowed Nene's people to take the canoes. The pā was burnt and destroyed.[39][40]

Ōhaeawai

George Clarke observed the effect of the battle of Kororāreka upon Phillpotts: "It galled him terribly, and the poor fellow took it as a reflection on his courage, and was very sore about it. It made him reckless, and he joined the camp with the foreboding that he should never return."[41]: 84

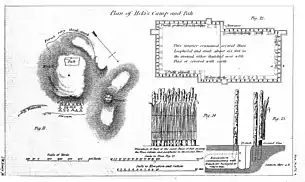

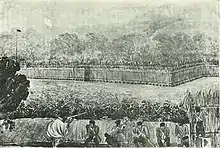

On 1 July 1845, during the battle of Ōhaeawai, after 32-pounder bombardment of the pā, Colonel Henry Despard put his opinion to his council that the palisades had been loosened and an assault may be successful. Tāmati Wāka Nene advised Despard that there was no breach, and that "the bravest soldiers in the world could not find a passage for two abreast," and Captain William Biddlecomb Marlow, RE, supported him in this view. Colonel William Hulme, 96th Regiment, Captain Johnson, RN, and Marlow protested against Despard's intentions.[41]: 85 In consequence, Phillpotts, alone and unarmed, made a daring reconnaissance, walking round the pā to within pistol-shot of the palisades targeted by the gun; so close that his acquaintances within called out "Go back Topi. We cannot let you come nearer, Topi; if you do we must fire". When shots were fired over his head, he exchanged some good-natured chaff with them and sauntered back to British lines.[1]

Perhaps it was not his first reconnaissance. Surveyor Johann Pieter (John Peter) Du Moulin, attached to the Commissariat, noted:

Some days previous to the assault, it was suggested to the commanding officer that a breach might be effected by powder bags. Philpotts volunteered to perform that duty, for which he was snubbed. He then, out of bravado, left the camp, in mid-day, unarmed, and reached the pa to within a few yards; when a native climbed the second row of palisades, and called out, in broken English,—"go back, Toby, or else you will be shot." I was an eye-witness to this piece of foolery. Philpotts was attired in a blue shirt, and (fancy) a tall white felt hat.[42]

Clarke recalled that, on another occasion:

a little after dusk, Phillpotts crept up to the palisade, and began slashing with his cutlass at the flax screen, when, of course, nothing could have been easier than to strike him down, but instead of that an awful voice came from the ground at his feet, not five yards off: "Go away Toby, go away Toby," and he went away.[41]: 85

Phillpotts reported that an assault was impracticable. Tamati Waaka Nene warned Despard again that an assault was absolutely impossible. Even Frederick Manning and John Webster, in Nene's presence, advised Despard against an assault.[43] Despard ordered an assault upon the pā to be made at 3:00 pm.[1]

The storming party was to be composed of columns; the advance made up of 2 sergeants and 20 volunteers who were to silently move up to the stockade; followed closely by the assaulting body under Major Ewan Macpherson, 99th Regiment—40 grenadiers of the 58th, 40 grenadiers of the 99th, accompanied by the bluejackets and 30 volunteer militia pioneers carrying hatchets, ropes and ladders; closely followed by a column of 100 men under Major Cyprian Bridge, 58th Regiment—remaining grenadiers of the 58th, 60 battalion rank and file of the 58th, 40 light company rank and file of the 99th; and a supporting column of 100 men under Colonel Hulme, 96th Regiment—the 96th detachment complete with battalion rank and file of the 58th. Phillpotts, Captain William Grant, 58th Regiment, and Lieutenant Edward Beatty, 99th Regiment, took to leading the forlorn hope.[44][45]: 116 [41]: 84 [46]: 290–291

Du Moulin recalled that from the moment before marching off at 3:00 pm:

I left the camp for the knoll, a few hundred yards off, (on the top of which a brass 6-pounder was placed, and at the base a 32-pounder naval gun,) for the purpose of witnessing the assault. On arriving at the naval gun, Philpotts overtook me, and said,—"Here, Mullins, pull these trousers off; I don't want to die a soldier." (They were black cloth, red stripe, soldier's trousers.) He sat on the gun carriage, and I hauled the trousers off, over his boots. He then drew his sword, threw the scabbard into the fern; his forage cap, a soldier's, after the scabbard; and left, attired in a sailor's blue woollen shirt, tight cotton drawers, boots, and naked sword. He followed Major Macpherson's attacking column, which passed us a short distance off. I soon followed Philpotts, instead of going to the top of the knoll; and when within sixty or seventy yards from the pa, I stood behind a dead tree, with my watch in hand. The two attacking columns were Major Bridge, 58th, with the light companies, 58th and 99th; Major Macpherson, 99th, with the grenadier companies. The reserve column under Colonel Hulme, mixed. On the two former reaching the pa, to within twenty-five yards, they received, nearly simultaneously, a fearful volley from the enemy, which killed Captain Grant, and caused a havock in a body of nearly four hundred of the finest of troops, which threw the whole of the two columns into a mass of confusion. The natives continued independent firing, which killed Philpotts...[42]

Du Moulin's sketch plan placed Phillpotts' body just outside the palisade about halfway along the western flank. In a despatch to the Governor, Despard placed Phillpotts endeavouring to force his way through the palisade.[44] Historian James Cowan says that Phillpotts had run: "along the stockade to the right (the west flank), seeking a place to enter; the outer fence had suffered most damage there. He actually climbed the pekerangi, a small portion of which had been loosened by sword-cuts delivered against the torotoro lashings and partly pulled down. There he fell, shot through the body."[43] Other accounts place Phillpotts as having worked his way through the pā's gun embrasure, or breech in the outer palisade, and whilst endeavouring to force a way through the second palisade, was struck through the heart by a stray ball.[47][2] Arthur McCormick's 1908 illustration imagines him there, beside one of the pā's guns, striking in naval full dress coatee with epaulette and clean white trousers, arm embowed, holding in the hand a sword.

A flag of truce was flown from the pā two days later, with invitation to bury the dead. Cowan's informants recalled that as casualties were carried from the field, the pā 's victors charged out yelling, shaking guns and long-handled tomahawks. A white-headed tattooed warrior ran along the palisade to Phillpotts's body, bent over, cut off a portion of scalp with his tomahawk and burst into incantation offering the first battle-trophy to his god of war, Tūmatauenga. Warriors then performed the tutu-ngarahu war dance with guns and tomahawks. John Webster recalled that a war cry was danced when Phillpotts' scalped body was found.[47][46]: 290–291

Archdeacon Henry Williams, in recovering Phillpotts' body, also recovered his eyeglass and a portion of his scalp, found hanging by the inner palisade it was said, which he passed over the Captain Johnson, RN, HMS Hazard.[47][48] Tāmati Wāka Nene recovered Phillpotts' sword which had been held over within Ohaeawai's palisades during recovery of bodies. He later gave it to the Rev. William Davis.[49]

Grant, who'd fallen shot through the head, was later found with additional damage to his body. He and Phillpotts and were buried at St. John the Baptist Church, Waimate."[41]: 85 [50] Beatty, severely wounded in the attack, died of wounds at Waimate on 11 July.[51]

Legacy

George Phillpotts collected a number of Fijian weapons, possibly during HMS Hazard's South Sea cruises in 1843–44:[52]

- A Fijian sokilaki or long barbed spear. Accession no. E1616, Royal Albert Memorial Museum.[53]

- A Fijian paddle club. Accession no. E1248, Royal Albert Memorial Museum[54]

- A Fijian club or battle-hammer carved in the form of a stylised flying fox fruit bat, Pteropus. Accession no. E1607, Royal Albert Memorial Museum[55]

Arms of Phillpotts

Escutcheon—Gules a cross argent between four swords erect argent, pommels and hilts or. Crest—A dexter arm embowed in armour, holding in the hand a sword all proper.[56][9][57]

References

- Kenny, Henry Eyre (January 1912). "Pen and Ink Sketches of Officers Commanding the Forces in New Zealand from 1845 to 1870". New Zealand Military Journal.

- "Maori Memories (by J.H.S for "The Daily Times."): Phillpott's Fate". Wairarapa Daily Times. 8 September 1934. p. 4.

- "St John the Baptist – Waimate North". Waimate North Church Parishes. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- Charles Haultain, ed. (1844). The New Navy List. London: Simpkin, Marshall and Co. p. 226.

- "Narrative of Events at the Bay of Islands". The New-Zealander. Vol. 1, no. 1. 7 June 1845. p. 2.

- "Despatches from Colonel Despard, to Governor Fitzroy". The New-Zealander. Vol. 1, no. 6. 12 July 1845. p. 2.

- "St Michael's Church, Ōhaeawai". New Zealand History. Research and Publishing Group, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- "Lieutenant George Phillpotts". Monument Australia. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- "Budock, St Budock". Cornish stained glass. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- Crawford, J A B. "George Phillpotts". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage.

- O'Byrne, William R. A Naval Biographical Dictionary. London: John Murray. p. 902.

- Charles Haultain, ed. (1840). The New Navy List. London: Simpkin, Marshall and Co.

- Hart, Henry George (1841). The New Army List for 1841. London: John Murray. p. 7.

- Dyott, William (1907). Jeffrey, Reginald W (ed.). Dyott's Diary, 1781–1845: A Selection from the Journal of William Dyott, Sometime General in the British Army and Aide-de-camp to his Majesty King George III. Vol. 2. London: Archibald Constable and Company, Ltd. p. 330.

- Charles Haultain, ed. (1843). The New Navy List. London: Simpkin, Marshall and Co.

- Low, Charles Rathbone (1877). History of the Indian Navy. (1613-1863). Vol. 2. London: R. Bentley and Son.

- Burke, Edmund (1844). The Annual Register of or a View of the History and Politics of the Year 1843. Vol. 85. London: F & J Rivington. p. 515.

- Parkinson, Jonathan (2011). "Early Steam-Powered Navigation on the Lower Yangtse". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch. Hong Kong: Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch. 51: 64.

- "The Bristol Mercury". Bristol. 26 November 1842. p. 2.

- "Recorded Samples of The China 1842 Medal to the Royal Navy (Vixen)". British Medal Rolls. Orders and Medals Society of America. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- "Shipping Intelligence". The Australian. 16 December 1842. p. 2. Retrieved 1 April 2021 – via Trove.

- "The "No Coolie" Cry". The Australian. 23 January 1843. p. 2. Retrieved 28 November 2022 – via Trove.

- "Shipping Intelligence". Port Phillip Gazette. Vol. 5, no. 424. Victoria. 8 February 1843. p. 2. Retrieved 28 November 2022 – via Trove.

- "Shipping Intelligence". Port Phillip Gazette. Vol. 5, no. 440. Victoria. 5 April 1843. p. 2. Retrieved 28 November 2022 – via Trove.

- "Shipping Intelligence". The Colonial Observer. Vol. 2, no. 119. New South Wales. 12 April 1843. p. 10. Retrieved 28 November 2022 – via Trove.

- "Imports". Australasian Chronicle. Vol. 4, no. 554. New South Wales. 25 May 1843. p. 3. Retrieved 28 November 2022 – via Trove.

- "Shipping Intelligence". Morning Chronicle. Vol. 1, no. 66. New South Wales. 22 May 1844. p. 3. Retrieved 28 November 2022 – via Trove.

- "South Sea Islands". The Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser. Vol. 2, no. 73. New South Wales. 25 May 1844. p. 4. Retrieved 28 November 2022 – via Trove.

- "Sandwich Islands". The Courier (Hobart). Vol. 17, no. 967. Tasmania. 7 June 1844. p. 4. Retrieved 28 November 2022 – via Trove.

- "Imports". The Australian. 20 May 1844. p. 2. Retrieved 28 November 2022 – via Trove.

- "The French at Tahiti". The Australian. 20 May 1844. p. 3. Retrieved 28 November 2022 – via Trove.

- "Shipping Intelligence". Morning Chronicle. Vol. 1, no. 66. New South Wales. 22 May 1844. p. 3. Retrieved 28 November 2022 – via Trove.

- "Departures". The Sydney Morning Herald. 5 July 1844. p. 2. Retrieved 7 November 2021 – via Trove.

- "Papers of Admiral David Robertson-Macdonald". Richard M Ford Ltd. 2021. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- "Admiral David Robertson-Macdonald". Auckland Libraries Heritage Images Collection. 2021. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- Carleton, Hugh (1877). The Life of Henry Williams: Archdeacon of Waimate. Vol. 2. Auckland: Wilson & Horton – via Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library.

- "The Sacking of Kororareka". Ministry for Culture and Heritage – NZ History online. 3 April 2009. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- "Copies or Extracts of Correspondence Relative to an Attack on the British Settlement at the Bay of Islands by the Natives of New Zealand", Accounts and Papers of the House of Commons: Papers Relative to the Affairs of New Zealand, vol. 33, pp. 18–19, 1845

- "Narrative of Events at the Bay of Islands". The New-Zealander. Vol. 1, no. 1. 7 June 1845. p. 2.

- Reeves, William Pember (1895). "Death of Haueaki". The New Zealand Reader. Wellington: Samuel Costall. pp. 180–184.

- Clarke, George (1903). Notes on Early Life in New Zealand. Hobart: J. Walch & Sons.

- Carleton, Hugh (1877). The Life of Henry Williams, Archdeacon of Waimate. Vol. 2. Auckland: Wilsons & Horton. p. 150 – via NZETC.

- Cowan, James (1955). The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period. Vol. 1 (1845–64) – via NZETC.

- "Government Gazette". Auckland Times. Vol. 3, no. 131. 12 July 1845. p. 4.

- Thomson, Arthur Saunders (1859). The Story of New Zealand: Past and Present—Savage and Civilised. Vol. 2. London: John Murray.

- Webster, John (1908). Reminiscences of an Old Settler in Australia and New Zealand. Christchurch: Whitcombe & Tombs.

- "Bay of Islands". The New-Zealander. Vol. 1, no. 6. 12 July 1845. p. 2.

- "Colonel Despard's Despatch". The Wellington Independent. Vol. 1, no. 29. 26 November 1845. p. 4.

- "A Relic of Heke's War". The New Zealand Illustrated Magazine. Vol. 6, no. 5. 1 August 1902. p. 385.

- Bedggood, W.E. (1971). Brief History of St John Baptist Church Te Waimate. News, Kaikohe.

- "Died". The New-Zealander. Vol. 1, no. 10. 9 August 1845. p. 2.

- "Shipping Intelligence". Port Phillip Gazette. Vol. 5, no. 424. Victoria. 8 February 1843. p. 2. Retrieved 28 November 2022 – via Trove.

- "Spear". RAAM Collections. Exeter: Royal Albert Memorial Museum & Art Gallery. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- "Club". RAAM Collections. Exeter: Royal Albert Memorial Museum & Art Gallery. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- "Club". RAAM Collections. Exeter: Royal Albert Memorial Museum & Art Gallery. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- Burke, Bernard (1884). The General Armory of England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales. London: Harrison & Sons. p. 800.

- "Truro, Bishop Phillpotts' Library". Cornish stained glass. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

External links

- "George Philpotts". Online Cenotaph. Auckland War Memorial Museum. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- Crawford, J A B (1990). "Phillpotts, George". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Te Ara - The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- O'Byrne, William Richard (1849). . . John Murray – via Wikisource.