George Reginald Starr

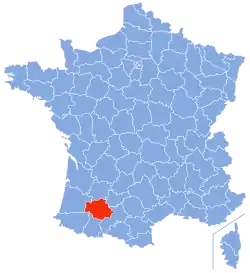

George Reginald Starr (6 April 1904 – 2 September 1980), code name Hilaire, was a British mining engineer and an agent of the United Kingdom's clandestine Special Operations Executive (SOE) organisation in World War II. He was the organiser (leader) of the Wheelwright network in southwestern France from November 1942 until the liberation of France from Nazi German occupation in September 1944. The purpose of SOE was to conduct espionage, sabotage and reconnaissance in occupied Europe against the Axis powers. SOE agents in France allied themselves with French Resistance groups and supplied them with weapons and equipment parachuted in from England.

George Starr | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname(s) | Hilaire |

| Born | 6 April 1904 London, England |

| Died | 2 September 1980 (aged 76) Senlis, France |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom/France |

| Service/ | Special Operations Executive, |

| Years of service | 1940–1944 |

| Rank | Lt. Colonel |

| Unit | Wheelwright Network |

| Awards | MBE, CBE, Legion d'honneur, Medal of Freedom |

He is continually making aggressive contradictions and assertions and is the worst type of know-all, namely one who is often right and can seldom be proved wrong.[1]

An SOE trainer on Starr

Yes, by Christ, I was a martinet. I had to be. I laughed and joked, but if somebody made a mistake, I'd cuss them. If it was serious out they went.[2]

Starr on himself

Starr's accomplishments include building up a large network of resistance groups, carrying out a number of sabotage operations in the months leading up to the Normandy invasion on 6 June 1944, rescuing from imprisonment about 50 important resistance leaders and allied airmen shot down over France, and participation as a leader in the liberation of southwestern France from German occupation. By mid-1944 Starr had more than 20 SOE agents working for him, second in numbers only to the earlier (and defunct) Prosper or Physician network.[3]

In the estimation of M.R.D. Foot, the official historian of the SOE, Starr was one of the half-dozen best agents of the SOE in France. He was one of only three SOE agents to be promoted to the rank of Lt. Colonel, along with Richard Heslop and Francis Cammaerts.[4] One of the French agents of the SOE, Philippe de Gunzbourg, compared Starr as a leader to Lawrence of Arabia.[5] Starr's wartime record was not, however, without controversy. He had a confrontation with Charles de Gaulle after the liberation of France, and one of his agents, Anne-Marie Walters, accused him of permitting the torture of captured collaborators.

Starr's brother, John Renshaw Starr, was also an SOE agent.

Early life

He was born in London on 6 April 1904, one of two sons of Alfred Demarest Starr, an American bookkeeper who became a naturalised British subject, and Englishwoman Ethel Renshaw. He was a grandson of William Robert Renshaw. He was educated at Ardingly College, and at the age of 16, undertook a four-year apprenticeship as a coal-miner in Shropshire. After studying mining engineering at the Royal School of Mines, Imperial College London, he joined the Glasgow firm of Mather and Coulson Ltd, manufacturers of mining equipment. He worked in several countries in Europe installing mine equipment. Starr's second wife, Pilar Canudas Ristol, who he met in Spain, worked in Spain for SOE during World War II.[6]

Starr was described by his wireless operator, Yvonne Cormeau, as short in stature, five feet six inches in height, very nervous, a heavy cigarette smoker, and a man who took duty and responsibility seriously and would never ask a person to do anything he would not do himself. Cormeau was his closest associate, "confidante and, a few alleged, his lover."[7][8]

World War II

Building a network

Starr was working in Liège Province, Belgium in 1940 when the German invasion began. He escaped back to England with British forces in the Dunkirk evacuation. He joined the British Army, being commissioned on the General List. He was subsequently recruited into the Special Operations Executive (SOE) for his language skills[9] (although his spoken French was described as "atrocious") and given the code name Hilaire.[10]

On 3 November 1942 Starr arrived by boat with several other SOE agents at Port Miou on the Mediterranean coast of Vichy France. A few days later the Germans occupied Vichy which made SOE operations there must more dangerous than previously. Starr was scheduled to go to Lyon to work there, but the Lyon SOE network was penetrated in October 1942 and the agents arrested. SOE agent Henri Sevenet persuaded Starr to go instead to the Gascony region in southwestern France where a resistance movement was forming.[11] His instincts were correct. SOE networks were more secure in rural areas which had a much smaller presence of German soldiers and milice, the pro-German French militia, than large urban areas.[12]

Starr based himself in Castelnau-sur-l'Auvignon, a rural village of 300 persons, without running water or electricity. Local leaders were sympathetic to the resistance and the nearest Germans to the village were in the city of Agen, 35 kilometres (22 mi) distant. Starr posed as a retired Belgian mining engineer who had made a fortune in the Congo. From Castelnau, Starr began to build up a local resistance movement, called by SOE the Wheelwright Network (or Circuit). Starr was very conscious of security, communicating with his contacts only through couriers or the spoken word, never putting words to paper, and building up his network one trusted associate at a time. In January 1943, the SOE in London parachuted weapons and explosives into Castelnau. They were hidden in a medieval dungeon beneath the church in the village. Starr's ability to call on the United Kingdom to provide weapons made him a power among the nascent rural resistance organisations called maquis (whose members were called maquisards). Also, in January 1943, Starr borrowed a wireless operator from another network to facilitate communication with SOE in London.[13]

These initial successes aside, in spring 1943, seemingly forgotten by SOE headquarters in London, Starr was suffering from a skin disease probably caused by stress and contemplating failure and the abandonment of his mission. He sent Denise Bloch, an SOE agent on the run from another part of France, to Spain and hence to England with a written report (violating his own rule against written communication) requesting money and a wireless operator of his own. London's immediate answer was to send an aeroplane to hover over Castelnau to communicate with Starr by short-range S-Phone to determine that he was still alive. Starr affirmed his existence by greeting the pilot with a string of expletives and finally got attention from London. It was soon "raining containers" full of arms and equipment for the maquis.[14] Starr's SOE team would expand to include explosives expert Claude Arnault, wireless operator Yvonne Cormeau, and courier Anne-Marie Walters.

All did not go smoothly, however, in the fractious world of the French Resistance. Starr had setbacks, rivals and enemies, some of whom he managed to marginalise. The Germans arrested several of his trusted associates.[15] Starr was accused of being a "warlord," a law unto himself, and independent of the French Resistance to the German occupation.[16]

Security

M.R.D Foot said that the motto of every successful secret agent was "dubito, ergo sum" ("I doubt, therefore I survive."), and Starr is on a short list of agents who survived by paying careful attention to security.[17] Starr's caution extended to the people he worked with. On the boat which brought him to France in 1942 he complained about being "in charge of three bloody women," Marie-Thérèse Le Chêne, Mary Katherine Herbert, and Odette Sansom, all SOE agents. He took a special dislike to Sansom, who would become one of the most honoured SOE agents. In December 1942, he was suspicious of another SOE agent, Denise Bloch, who was fleeing from the Gestapo. He initially thought her to be a nuisance and contemplated her "liquidation," but learned to trust her, sending her back to the United Kingdom with an appeal for SOE assistance to his network. Starr also broke with Henri Sevenet, the Frenchman who had brought him to southwestern France and helped him become established.[18] Among his complaints about his courier, Anne-Marie Walters, was that she wore "high Paris fashion," thus violating his principle of being inconspicuous.[19]

Sabotage

The maquisards and their leaders wanted to begin harassing Germans as resistance forces were doing elsewhere in France.[20] In December 1943 Starr requested and received permission from SOE headquarters to begin attacking the Gestapo and railroads in his region. On New Year's Eve 1943, Starr reported that the maquisards he had trained had destroyed more than 300 locomotives by carefully placing explosives on the engines.[21]

The National Gunpowder Factory near the city of Toulouse was a high priority for destruction by the allies. However, a daylight bombing raid by the Royal Air Force would kill many of the 6,000 French workers at the factory. London asked Starr to try to destroy the 'factory as an alternative to bombing. In March 1944 Claude Arnault and Anne-Marie Walters smuggled explosives to Toulouse. On 28 March, Arnault sneaked into the plant at night, placed explosives, and destroyed 30 electric motors out of 31 in the 'factory which were used to grind gunpowder. The factory was out of operation for six weeks.[22]

In April and May 1944, the resistance carried out a number of additional sabotage operations against factories and railroads, including a factory near Lourdes which made parts for aeroplanes and armoured vehicles. Arnault repeated his earlier success by sneaking into the factory at night along with three other men and destroying machinery with explosives.[23]

Sabotage successes notwithstanding, the French resistance was impatient in the early months of 1944. The French were beginning to lose confidence that the allies would ever invade France and liberate the country from German occupation. The joke circulated that "the English will fight to the last Frenchman."[24]

Battle of Castelnau

With the Normandy Invasion on 6 June 1944, the SOE wanted the maquisards to convert from being saboteurs to armed fighters directly contesting German forces. Starr began distributing arms to resistance groups. Starr collected 300 men, one-half French and one-half Spanish, at Castelnau sur l'Auvignon and prepared to begin an armed uprising against the Germans. The Spaniards in Starr's forces were former members of the Spanish Republican Army who had fled to France after their defeat in the Spanish Civil War. Many of them were communists. Starr was one of only a few SOE agents who was able to persuade the feuding communists and non-communists to join together to form a single resistance force.[25][26][27]

However, the Germans learned that Castelnau was Starr's base and on 21 June an estimated 1,500 soldiers of the German army attacked. Nineteen of the maquisards were killed and the Germans captured the village. A rear guard blew up the explosives left behind during the retreat, destroying most of the village. The Germans completed the destruction. Starr and his surviving maquisards retreated all the way to the hamlet of Lannemaignan, 55 kilometres (34 mi) west of Castelnau. Another eleven maquisards died during the retreat. On 2 July, the Germans attacked Lannemaignan with artillery and bombers. Still on the run, Starr led the maquisards south 20 kilometres (12 mi) to the town of Panjas where he joined forces with his friend, the French resistance leader Maurice Parisot. Starr's men became part of the Armagnac Battalion with Parisot as the commander. Starr became his adviser.[28][29]

Armagnac Battalion

The Armagnac Battalion was a polyglot collection of 1,900 men of a dozen different nationalities who came together in June 1944 after the Normandy landings. After the battle of Castelnau and other conflict, the men of the various resistance groups making up the battalion, including Starr's, were short of ammunition. Starr was ordered by SOE headquarters to attack German army units, but his pleas for air-drops of ammunition were ignored. Angered, he sent a wireless message to London saying, "I have given orders to the men under my command to manufacture bows and arrows. As soon as this is completed, we will attack and destroy these fucking divisions." The message got London's attention and ammunition supplies began arriving.[30]

The battalion fought a battle with units of the German Das Reich Division at Estang on 2 July, but was forced to abandon its positions by German bombing. On 14 July, 4,000 Germans were advancing on the Armagnac Battalion but, inexplicably, withdrew toward Toulouse. On 12 August, the Armagnacs liberated the village of Aire-sur-l'Adour with little loss and on 20–21 August surrounded and accepted the surrender of 192 Germans, including two colonels, at L'Isle-Jourdain, only 20 kilometres (12 mi) from Toulouse, the largest city in the region, the objective of the Armagnacs, and the stronghold of the remnants of the German army in the region. Starr, long accustomed to the shadows of the war, now donned his British uniform and led columns of men.[31]

On 21 August, Toulouse fell to the French Forces of the Interior, the umbrella organisation of resistance fighters. Starr and Yvonne Cormeau drove into the city, American and British flags on their car. The liberation of southwestern France was complete. However, the leader of the Armagnac Battalion, Maurice Parisot, was killed on 6 September; while an American aeroplane was landing, a propeller broke away from the motor and struck him.[32]

Starr and De Gaulle

The withdrawal of the Germans from southwestern France left the area in political chaos in which "feudal barons," of whom Starr was among the most important, took control. On 16 September 1944, General Charles de Gaulle, head of the Provisional Government of the French Republic, visited Toulouse. De Gaulle had little respect for the Resistance which had varying philosophies among its different groups of how France should be governed post-war. On meeting Starr and other resistance leaders, De Gaulle denounced them as mercenaries. He ordered Starr to leave France. Starr replied that he was in France under the authority of the allies and he did not recognise De Gaulle as his superior officer. De Gaulle threatened to arrest him but Starr stood his ground, and the meeting ended with a handshake. Nine days later, on 25 September, Starr and his wireless operator, Yvonne Cormeau, made a hasty departure from France.[33]

De Gaulle's reaction to Starr and the resistance fighters reflected De Gaulle's "obsession with restoring the authority of the state and allowing no challenges to its – to his – authority."[34]

Allegations of torture

When I got back to England, I faced a court of enquiry for ill-treating German prisoners. Anne-Marie Walters had started it because she hated my guts because I threw her out of France and sent her home for indiscipline. Very lucky I didn't have her shot.[35]

Starr, an interview with the Imperial War Museum.

In late July 1944, Starr ordered his youthful courier, Anne-Marie Walters, to leave France accusing her of disobedience. When Walters returned to London, she said that Starr had countenanced torture of French collaborators with the Germans. On 1 November 1944, Starr, who had returned to London, was interviewed by SOE. He recounted "with relish" an incident of torture, causing consternation in the SOE although the interviewers said that he could not be blamed for the tortures committed by the French Resistance. In February 1945, a court of enquiry with testimony from Starr, Walters, and others took place. The part of the transcript of the enquiry containing Walter's testimony has disappeared from the record. On 28 February, the conclusion of the "rather perfunctory court of enquiry" (in the words of M.R.D. Foot),[36] was that "there is no justification whatever for any imputation against Lt. Col. Starr of inhumanity or cruel treatment to any prisoner at any time under his control or under the control or troops or resistance forces under his immediate command or control."[37]

Post-war

After the war, Starr was sent to Essen in the Ruhr district to direct the re-opening of German coal mines. He later returned to his previous employer, Mather and Coulson, as managing director before retiring to live in France.[38]

Starr died in a hospital in Senlis, France on 2 September 1980.[39]

Awards

| UK | Distinguished Service Order | |

| UK | Military Cross | |

| France | Légion d'honneur (Officier) | |

| France | Croix de Guerre with palm | |

| USA | Medal of Freedom with silver palm |

References

- Hewson, David in Walters, Anne-Marie (2009), Moondrop to Gascony, Wiltshire: Moho Books, p. 22

- Hewson, p. 267

- Foot, M.R.D. (1966), SOE in France, London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, pp. 147, 377–378

- Foot, pp. 42, 311, 412.

- Hastings, Max (2014), Das Reich, St. Paul, MN: MBI Publishing Company, p. 63

- Hewson, p. 22

- "CORMEAU, YVONNE BEATRICE (ORAL HISTORY)". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- Glass, Charles (2018), They Fought Alone, New York: Penguin Press, p. 8, 103.

- "BBC Historic Figures – George Starr (1904–1980)". BBC. Retrieved 18 May 2008.

- Glass, p. 26

- Glass, pp. 10–12, 28–29

- Fuller, Jean Overton (1975). The German Penetration of SOE. London: William Kimber. p. 147. ISBN 0718300645.

- Glass, pp. 39–54, 56–57

- Glass, pp. 72–79

- Glass, pp. 114–118, 128–133

- Gildea, Robert (2015), Fighters in the Shadows, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 363

- Foot, p. 311

- Glass, Charles (2018), They Fought Alone New York: Penquin Press, pp 10–11, 46–48

- Hastings, Max (2013), Das Reich, Minneapolis: Zenith Press, p. 66

- Glass, 133–134

- Glass, 133–134, 141

- Glass, pp. 155–156

- Glass, pp. 165–167

- Glass, p. 154

- Foot, p. 138

- Gildea, p. 363

- Glass, p. 171

- Escott, Beryl E. (2010), The Heroines of SOE, Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press, pp. 138–139

- Glass, pp. 192–196, 200

- Glass, pp. 201–202

- Glass, pp. 202–217

- Glass, pp. 219–228

- Foot, pp. 419–420

- Jackson, Julian (2018), De Gaulle, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, p. 18

- Hewson, p. 267

- Foot, p. 436

- Hewson, pp. 233–235

- Hewson, p. 24

- "George Reginald Starr," . Retrieved 21 December 2019