George Washington (inventor)

George Constant Louis Washington[I] (May 20, 1871 – March 29, 1946) was a Belgian inventor and businessman. He is best remembered for his improvement of an early instant coffee process and for the company he founded to mass-produce it, the G. Washington Coffee Company.[1]

George Washington | |

|---|---|

| Born | May 20, 1871 |

| Died | March 29, 1946 (aged 74) |

| Education | University of Bonn |

| Known for | G. Washington Coffee Company |

| Children | George Washington, Jr. |

An emigrant from his native Belgium, he arrived in the New York area in 1897. He dabbled in several technical fields before hitting upon manufacturing an adapted version of the nascent instant coffee, during a sojourn in Central America in 1906 or 1907. He began selling his coffee in 1909 and founded a company to manufacture it in 1910. Based in New York and New Jersey, his company prospered and became an important military supplier during World War I. The company's products were also advertised in New York newspapers and on the radio. The success of his company made Washington wealthy, and he lived in a mansion in Brooklyn and then moved to a country estate in New Jersey in 1927. In that same year, he lost a dispute with the tax authorities. Washington was married and had three children.

Washington's company was sold to American Home Products in 1943, shortly before his death. Though the coffee brand was discontinued by 1961, Washington's name is still used today in the product G. Washington's Seasoning & Broth.

Early life

George Washington was born in Kortrijk, Belgium to Jean Guillaume Washington (John William Washington) of England and Marie Louise Tant of Belgium, on May 20, 1871.[II][2][3][4] Following then-current nationality law, which considered fatherhood primary, Washington was a British subject until he was naturalized as an American in May 1918.[5] At least six siblings in the family also settled in different parts of the United States and Central America.[1] A number of accounts claim a relation to U.S. President George Washington, but this is not clearly explained.[6]

Washington came to reside in Brussels and also attained a degree in chemistry at the University of Bonn in Germany.[3] In December 1895, Washington married Angeline Céline Virginie (later, just "Lina") Van Nieuwenhuyse (born 1876), also from Belgium.[2][7] The US Census of 1900 records that Lina, like her husband, had English and Belgian ancestry (a Belgian father and an English mother).[2] The Washingtons' arrival in the United States on a ship from Antwerp, Belgium, on October 6, 1896, was recorded at Ellis Island, though the 1900 US Census states that they emigrated to the United States in 1897.[2] The Washingtons settled in the New York area, where they had three children:[2][8] Louisa Washington (born May 1897),[2] Irene Washington (born May 1898),[2] and George Washington Jr. (born August 1899).[2][9]

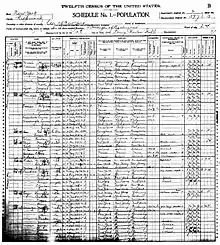

After arriving in the New York area, Washington founded a company producing kerosene gas mantles.[1] At this time, they lived in New Brighton on Staten Island, but his company, George Washington Lighting Company, was based in nearby Jersey City. This business was abandoned with the maturation of incandescent light bulb technology.[3] Washington also had a camera company for a time. By the time of the 1900 US Census, Washington, recorded in the census as an inventor, was 29 years old and living in a rented house in Brooklyn with his 23-year-old wife, their three young children, his younger sister (age 25), three servants, and a child of two of the servants.[2]

Washington tried his hand at cattle ranching[3] in Guatemala in 1906[10][11] or 1907[3] while, in the meantime, developed his instant coffee process. Washington returned to New York City after only a period of about a year[1] in Guatemala, and then began pursuing the main part of his career in coffee manufacture. His father remained in Guatemala and died there in 1912.

Personal life

After his coffee business was established in 1910, Washington resided at a Park Slope mansion, occupying half of a city block, at 47 Prospect Park West in Brooklyn,[5] and also at an 18-bedroom country home, later known as "Washington Lodge", on a 40-acre waterfront estate at 287 South Country Road in Brookhaven, New York, near Bellport in Suffolk County, which included the largest concrete swimming pool in New York at the time.[12][IV] Two attempted sales of the property, one in May 1926 for $150,000[13] and another in 1927, fell through.[14][15][16][17] In 1938, Washington's younger sister, Mrs. Kenneth Merkel, along with her husband and son, moved to the estate on South Country Road.[18] George Washington continued to own his estate until January 1943 when it was sold to Nathan Edelstein.[19] The Washington Lodge was then operated as a hotel and restaurant,[20][21] and large wedding receptions were held there.[22] Washington Lodge was sold to Murray Wunderlich in 1950[23] and after 1952 was operated as a children's camp.[24] In 1959, there was an attempt to have the estate rezoned so that it could again be used for a hotel.[25] The Washington Lodge was sold to the Catholic Marist Brothers of the Schools as a summer retreat in 1960,[26][27] and beginning in September 1970 was leased to the Bay Community School during the school year.[28] Recently, the Washington Lodge estate was divided, and there have been conservation projects by local nonprofits and Bellport resident Isabella Rossellini.[29] The Washington Lodge still stands, and is being used and restored by the Center for Environmental Education and Discovery, a nature center.[30]

With his company's relocation to New Jersey, following the purchase of land there in 1927, he moved to the former estate of Governor Franklin Murphy at "Franklin Farms" in Mendham.[31] Washington was a lover of exotic animals, as well as gardening.[12] He maintained extensive menageries on his country properties, first at Bellport, and later at Mendham. On Long Island, it is reported that he was often seen with a bird or monkey on his shoulder.[12] At both his menageries, Washington specialized in rare birds,[3][15] but such animals as deer, sheep, goats, and antelope are also recorded at Bellport,[15] and deer, llamas, and zebras are recorded among the hundreds of animals in the larger space at Mendham.[1] Socially, he was an active member of the Lotos Club, a literary gentlemen's club in New York City.[1]

Washington's name was briefly put forward for the 1920 presidential election in South Dakota's preference primary for the "American Party", although papers were filed too late to be valid.[5] There is no indication, however, that the nomination was serious. George Washington would not have been eligible for that office, in any case, as he was foreign-born. There have been several "American Party"s in history—it is unclear if the nomination was a particular satire on any so-named movement at the time.[III]

That's the fellow. He has put one over on us. He has a barrel of money—enough to run a slambang campaign. Why, don't you remember, he just bought that $100,000 mansion from Albert Feltman on Prospect Park West. He's learned a lot about politics by being a neighbor of Senator Calder and George Hamlin Childs. And when you come to think of it, that American Party stuff is good campaign dope this year, what with all the Bolsheviki and the Government after the Reds and the row about the League of Nations, and all that. We've been overlooking something for sure.

— Brooklyn politician (unnamed), The New York Times, 4 January 1920

Invention and business

George Washington held over two dozen patents, in the fields of hydrocarbon lamps, cameras, and food processing. He was not the first to invent an instant coffee process, David Strang in New Zealand had the first patent in 1890 (Number 3518)[32] for instant or soluble coffee and was sold under the name Strangs Coffee,[33] another was chemist Satori Kato's work was a precursor, among others, but Washington's invention was the first effort that led to large scale commercial manufacture. There is some suggestion that he was inspired by seeing dried powder on the edge of a silver coffee pot while in Guatemala.[34] Federico Lehnhoff Wyld, a German-Guatemalan doctor, along with Eduardo T. Cabarrus, also developed an instant coffee process about this time,[11] which he later marketed in Europe; as Wyld was Washington's personal physician, there is some suggestion that their discoveries were not independent.[10]

Washington's product was first marketed as Red E Coffee (a pun on "ready") in 1909, and the G. Washington Coffee Refining Company was founded in 1910.[10] Washington's first production plant was at 147 41st Street in Brooklyn's Bush Terminal industrial complex. The company later moved operations to New Jersey, acquiring the land for the new plant at 45 East Hanover Avenue in Morris Plains in 1927.[31][IV]

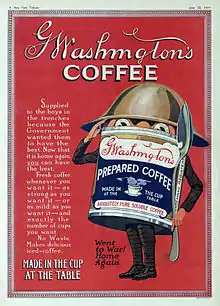

Advertising for the company's product often emphasized its supposed convenience, modernity, and purity. It was claimed to be better for digestion, and even that the "pure" coffee did not have the wakefulness effect of coffee from ground beans (a direct effect of caffeine content, present in both forms). After World War I ended, the American military's use of the coffee became another selling point. A different avenue for promotion came when the company sponsored The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes radio series on NBC and its Blue Network from 1930 to 1935, which started with Dr. Watson welcoming listeners to his recollections told by "a blazing fire and a cup of G Washington brewing."[35] Other radio sponsorships were for O'Henry Stories (1932, NBC Blue), Professor Quiz (1936, CBS), Uncle Jim's Question Bee (1936–39, NBC Blue), and Surprise Party (1946–47, CBS).[36]

But the early instant coffee was also often considered of poor quality, of disagreeable taste, and little more than a novelty product.[37]

Washington experienced some tax trouble with federal authorities, concerning the financial relationship between himself and his company. In November 1918, he contracted with the company for the use of his trade secrets in the manufacture of the coffee, and a month later gave a four-fifths stake in this to his immediate family. The Washingtons insisted that taxes needn't be paid on the family members' income, and the case went first to the Board of Tax Appeals, and then to the Court of Appeals, which in 1927 ruled against the Washingtons by a two-to-one decision. A petition to the Supreme Court was not accepted.[38]

Washington's son, George Washington, Jr., served for a time as treasurer of his father's company, and, like his father, dabbled in invention, patenting a widely used photoengraving process for newspapers that was introduced by Fairchild Camera and Instrument in 1948.[39]

Military contracts

Washington's at-that-time unique product saw major use as combat rations in World War I. Coffee consumption on the battlefield was seen as valuable since it gave soldiers a caffeine boost.[37] E.F. Holbrook, the head of the coffee section of the U.S. War Department at the time, also considered it an important aid in recovery from mustard gas.[10] It was employed by the Canadian Expeditionary Force from 1914 until the American Expeditionary Force entered the war in 1917, and all production was shifted toward American military use.[6] New, smaller producers also sprung up to meet the incredible level of demand from the Army, which in the final period of the war was six times the national supply.[11]

The instant coffee achieved some popularity with the soldiers, who nicknamed it a "cup of George." As the prime attraction was the caffeine boost, rather than the flavor, it was sometimes drunk cold.[11]

I am very happy despite the rats, the rain, the mud, the draughts [sic], the roar of the cannon and the scream of shells. It takes only a minute to light my little oil heater and make some George Washington Coffee ... Every night I offer up a special petition to the health and well-being of Mr. Washington.

— American soldier, 1918 letter from the trenches[11]

American emergency rations in World War I consisted of a quarter ounce (7 grams) packet of double-strength instant coffee, packed one per man in containers with multiple types of foods meant for twenty-four men.[6] Instant coffee was also used in reserve rations and trench rations. During World War II, the U.S. military again relied on Washington, but this time on an equal footing with the other major instant coffee brands that had emerged in the interwar period, most notably Nescafé, as well as the new companies formed to meet a renewed military demand.[37]

Final years

The G. Washington Coffee Refining Company was purchased by American Home Products in 1943, and George Washington retired. The purchase of the company, which was mostly held by the family, was in exchange for 29,860 shares (approx. $1.7 million) of American Home Products stock, at a time when American Home Products was in a period of intense buying, purchasing 34 companies in eight years.[40][41] Clarence Mark, general manager of G. Washington, succeeded Washington in running the merged unit.[40]

In Washington's final years, he sold the "Franklin Farms" property, and lived in a home on New Vernon Road in Mendham.[3]

He died three years after his company was sold, on March 29, 1946, in Mendham, New Jersey, after an illness, at the age of 74.[1] His funeral was held three days later.[42]

Legacy

G. Washington coffee was discontinued as a brand by 1961, when Washington's New Jersey plant was sold to Tenco, by then a division of The Coca-Cola Company.[37] The last remnant of the brand survives in G. Washington's Seasoning & Broth, a sideline developed in 1938. This brand was sold by American Home Products in 2000, and, after passing through a couple of intermediaries, has been run by Homestat Farm, Ltd. since 2001.[43]

Patents

- U.S. Patent 576,523

- U.S. Patent 576,524

- U.S. Patent 584,569

- U.S. Patent 589,051

- U.S. Patent 593,257

- U.S. Patent 607,974

- U.S. Patent 619,059

- U.S. Patent 706,504

- U.S. Patent 706,505

- U.S. Patent 730,498

- U.S. Patent 745,698

- U.S. Patent 760,670

- U.S. Patent 760,671

- U.S. Patent 760,672

- U.S. Patent 770,135

- U.S. Patent 770,836

- U.S. Patent 777,871

- U.S. Patent 778,518

- U.S. Patent 781,317

- U.S. Patent 1,504,459

- U.S. Patent 1,512,730

- U.S. Patent 1,512,731

- U.S. Patent 1,631,298

- U.S. Patent 1,631,299

- U.S. Patent 1,631,302

- U.S. Patent 1,631,303

Notes

- I^ : He does not appear to have used his full name while in the United States—it is absent from census and immigration records, his patent applications, and contemporary news articles about him.

- II^ : The New York Times gives the place of birth as Kortrijk, while The New York Herald Tribune gives Brussels. It is presumed that the more obscure city would be the less likely error. Belgian birth records clearly indicate that he was born on May 20, 1871 in Kortrijk, West-Vlaanderen, Belgium.[4]

- III^ : In 1920, former Texas governor James E. Ferguson actually ran under an "American Party" label.

- IV^ : The Morris Plains address at 45 Hanover Avenue is given in a 1928 ad;[44] the plant is described in the New York Times as adjoining the Morristown Line, so the address must be 45 East Hanover Avenue.

References

- "G. Washington, 74. Began Coffee Firm. Head of Refining Company for 33 Years Dies in Jersey. Founded Business in 1910. Head of Refining Company for 33 Years Dies in Jersey. Founded Business in 1910". New York Times. March 30, 1946.

- Image of census page containing George Washington; 1900 US Census; Staten Island; New York City

- "G. Washington Is Dead, Made Instant Coffee", The New York Herald Tribune, March 29, 1946.

- "Birth record George Washington". familysearch.

- "Presidency Candidate Found in Brooklyn", The New York Times, January 4, 1920.

- The Story of a Pantry Shelf: An Outline History of Grocery Specialties. New York: Butterick Publishing Company. 1925.

- "Mrs. George Washington" (1876–1952), obituary, The New York Times, October 30, 1952.

- The birthplace of the Washingtons' eldest daughter (born May 1897) is given in the 1900 US Census as Belgium, despite the Washingtons arriving at Ellis Island in October 1896. The US Census also records the year of their emigration to the USA as 1897. The other two children are recorded in the census as being born in New York.

- George Washington, Jr. was born on August 6, 1899, and died on December 1, 1966, in Morristown, New Jersey; Social Security Death Index.

- Ukers, William H. (1922). All about Coffee. The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal Co.

- Pendergrast, Mark (1999). Uncommon Grounds: The history of coffee and how it transformed our world. Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-05467-6.

- Principe, Victor (2002). Bellport Village & Brookhaven Hamlet, NY. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-0968-X.

- "Washington Estate at Bellport Sold". Suffolk County News. May 14, 1926. p. 1.

- "Washington Place, Bellport, Bought for a Country Club". Patchogue Advance. March 1, 1927. p. 1.

- "Big Bellport Sale", The New York Times, May 23, 1926.

- "Brooklyn Club Buys", The New York Times, February 25, 1927.

- "Park And Shore Club Memberships Now Open". Brooklyn Life and Activities of Long Island Society. April 9, 1927. p. 21.

- "Brookhaven". Patchogue Advance. June 14, 1938. p. 10.

- "Real Estate Dealings". Patchogue Advance. January 28, 1943. p. 7.

- "Upton Officers Guests At Washington Lodge". Patchogue Advance. August 31, 1944. p. 9.

- "Advertisement: Announcing The Opening of Washington Lodge, South Country Road, Brookhaven". Patchogue Advance. November 29, 1945. p. 14.

- "Notes on Nuptials, Piro-Meyer". Patchogue Advance. October 24, 1946. p. 5.

- "Speaking of Business". Patchogue Advance. June 15, 1950. p. 26.

- "Legal Advertisements". Patchogue Advance. February 28, 1952. p. 4.

- "Ask Washington Lodge Be Converted into Hotel". Patchogue Advance. September 17, 1959. p. 1.

- "Town Claims Tax Loss of $75,000; Machine 'Erred'". Patchogue Advance. June 30, 1960. p. 7.

- "Marist Brothers Property". Post-Morrow Foundation Newsletter. 15 (1). Summer 2011.

- "New Bay Community School to Open in September". Long Island Advance. June 18, 1970. p. 9.

- Duffy, Eileen M. (16 January 2013). "Isabella Rossellini Conserves 20 Acres for Agriculture in Brookhaven With Peconic Land Trust". Edible East End. Retrieved February 22, 2015.

- Leuzzi, Linda (March 12, 2014). "Finding a different route". Long Island Advance. Retrieved February 22, 2015.

- "Coffee Company Builds New Plant", The New York Times, May 26, 1927.

- "First Annual Report, New Zealand, Patents, Designs and Trade-marks". atojs.natlib.govt.nz. 1890. p. 9.

- "Kiwi gets credit for instant coffee". 14 January 2015.

- History of Instant Coffee Archived January 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Nestlé UK. Retrieved on March 31, 2007.

- Dunning, John (March 19, 1998). "Sherlock Holmes". On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-977078-6.

- Cox, Jim (2008). Sold on radio advertisers in the golden age of broadcasting. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co. p. 270. ISBN 978-0-7864-5176-0.

- Talbot, John M. (1997). "The Struggle for Control of a Commodity Chain: Instant Coffee from Latin America". Latin American Research Review 32 (2), 117–135.

- "George Washington Sues", The New York Times, May 26, 1927.

- "George Washington Jr. is Dead. Invented an Engraving Device". New York Times. December 27, 1966. Retrieved February 23, 2015.

George Washington Jr., former treasurer of the now defunct George Washington Coffee Company and inventor of a photo-electric engraver, a device widely used by newspapers, died today at Morristown Memorial Hospital. He was 67 years old and lived at 10 Harter Road.

- "To Buy Coffee Company", The New York Times, April 8, 1943.

- "Buy, Buy, Buy", Time, December 6, 1943.

- "Deaths", The New York Times, March 30, 1946.

- "History – G. Washington's Seasoning & Broth". Homestatfarm.com. Retrieved June 10, 2012.

- "George Washington's Instant Coffee - picture of advert". Retrieved June 10, 2012.

External links

- Coffee on the Instant - chapter in The Story of a Pantry Shelf: An Outline History of Grocery Specialties

- Official site of G. Washington's Seasoning & Broth