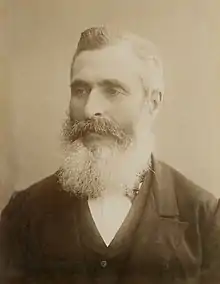

George W. Cotton

George Witherage Cotton (1821–1892) was a South Australian land dealer and Member of the South Australian Legislative Council. He was especially notable for being a champion of a scheme in South Australia to put working men onto small blocks of land (around 20 acres) on which they could carry out agricultural production.

Life

Cotton was born on 4 February 1821 at Staplehurst in Kent, England to Samuel and Lydia Cotton. He was apprenticed to a carpenter and studied at Wesley College, Sheffield for two years. After working in London he migrated with his wife, Mary Ann (Jull), and his parents to South Australia aboard the barque Athenian, arriving 5 March, 1849. His wife and son (William Jull Cotton) died shortly after their arrival and later in 1849 he married Elizabeth Mitchell with whom he had nine children.[1][2]

Upon arriving in South Australia, Cotton worked as a carpenter at Willunga and store-keeper on Hindmarsh Island. He then moved to Adelaide in 1862 and went into business as a land agent, becoming quite wealthy.

In 1865 Cotton called a meeting of laymen of the Wesleyan Church to consider the purchase of a site for a Wesleyan college in Adelaide.[1] This was to become Prince Alfred College, one of the most prominent schools in Adelaide, and Cotton was the founding Secretary, a position he held for twenty years.[2] In 1875, he was the first to import typewriters to Australia.[3]

In 1879 Cotton retired from real estate, leaving the business to his clerk Edward Andrew Devonshire Opie, an "old scholar" of Adelaide Educational Institution, and his son George Samuel Cotton, who followed his father as secretary of Prince Alfred College.[2]

In 1882 (at the age of 61), Cotton was elected to the Legislative Council.[4] In the depression years following he took an interest in the unemployed and in land reform. Cotton developed a working men's blocks scheme in which the government would offer blocks of up to 20 acres (8.1 ha) of crown land at low rents. The hope was that income from such blocks would eventually be adequate to support a family, forming the basis of a new society of independent producers and co-operative associations.[5]

In 1885 the South Australian government began to implement Cotton's plan. Blocks were surveyed and occupied in many parts of the colony, from Adelaide suburbs and country town fringes to the open country. In 1896 about 12,900 people, or nearly 4 per cent of the population, lived on them.

Cotton also championed the State Bank, technical education, a strong government department of labour, and boards of conciliation and arbitration. He was short-tempered and not an effective speaker despite being widely read.[1] In the 1880s he left the Wesleyans, whose indifference to reform enraged him, and declared a new faith: 'I worship a living Christ in the person of every child, however it may have been born into the world.'[1]

The depression affected Cotton's financial position to such a degree that in 1886 he was forced to resign his seat (as at that time members of the Legislative Council were unpaid).[2]

Cotton was a Fellow of the Royal Colonial Institute and the Royal Horticultural Society of London, a member of the British Economic Association and the Australasian Association for the Advancement of Science.[2]

Family

George Witherage Cotton (4 February 1821 – 15 December 1892) married Elizabeth Mitchell (1832 – 27 December 1901) with whom he had nine children, including:

- Mary Elizabeth Cotton (c. 1851 – 5 July 1862)

- Emma Morcom Cotton (c. 1853 – 31 July 1908), married William Bowen Chinner on 23 June 1875

- Samuel Mitchell Cotton (1854 - ?)

- George Samuel Cotton (22 February 1858 – 26 October 1918), married Annie Wallace on 15 July 1880

- William Mitchell Cotton L.R.C.P., M.R.C.S. (4 May 1860 – 21 April 1899), married Maude Pullein on 26 June 1888, died in London

- James Boorman Cotton (22 April 1862 – 9 May 1878), died at sea when mast collapsed

- Francis John Cotton (30 September 1868 – 18 April 1880), died after swimming accident

- Edward Witherage Cotton (1 March 1870 – 31 October 1941), married Mary Catherine Dempster on 5 September 1894. He was one of the first students at Roseworthy Agricultural College, under Professor John D. Custance, later a farmer in Western Australia.

- Charles Henry Cotton (23 September 1873 – 27 February 1947)

A sister, Jane Boorman Cotton (c. 1824 – 20 November 1910), married Claude Shuttleworth (c. 1819 – 27 May 1892), and conducted Hardwicke College for Girls.

Newspaper reports

Cotton's opinions attracted controversy, as extracts from newspapers of the day show.[6] For instance, in a spirited public debate on unemployment, a Thomas H. Smeaton, under the heading "Delusive Demagogues," said of Mr Cotton and his supporters: Dangerous men these at the present. Discard them working-men; they will fool you and nothing more...,[7] and another man wrote: He is a secret enemy, not an open fee, and in future it is the duty of all right-thinking men to treat his wordy vapourizings with the select contempt they deserve...[8]

The maligned politician sprang to defend himself on 13 April 1886, page 6f: Any man speaking of me as attempting to "gull" anybody can only be measuring me by some standard of his own to which course I respectfully demur to have judgments passed upon me...[9]

Another correspondent to the Register on 16 September 1886 complained: If [he] wishes his 300 to 400 pioneers on labourers' blocks to succeed he had with misleading statements, but rather ought to preach to them uninterrupted industry (no eight-hours system), the strictest of economy and an unlimited amount of self-denial.[10]

A further unsolicited opinion is given in the Register on 27 October 1886: [He is] a South Australians in finance, and yet every effort he makes seems to increase the fog through which we have to discover his meaning...[11]

A Rev Honner criticised Cotton's scheme in the Register, 15 February 1888, saying: If I may judge of those blocks by some I have seen, then they must be intended for blockheads, for no sane man would live on them, unless he was seeking a wilderness for the occupation of meditation.[12] But Cotton retorted on 17 February 1888: I hope when the historian has to look back at the difficulties small holdings had to encounter... that there will not be "perils among false brethren" to be received as amongst the bitterest opposition.[13]

Another citizen entered the fray on 22 February 1888: For some years past Mr Cotton has been energetically blowing his own trumpet from the homestead blocks. Some of us working men are growing tired of [it]:

Cotton's the man for all jobs,

He scowls on all the nobs,

He winks and shouts at the snobs,

And he sighs for the Government's bobs.[14]

Yet another citizen offered an unflattering opinion of Cotton in the Register, 4 August 1890: ...They distrust him; they do not know in what category of politicians to place him; he really stands alone. Sometimes he seems radical and appears is the advocate of thorough reform; at others he opposes the very things which would more than any other benefit the workers...[15]

In the heat of a public debate on the "land question" a correspondent to the Register on 31 July 1888 puts the following to Cotton: Must a man be a landjobber before he can honestly propose land reform? And is the only honest politician the land agent who opposes land nationalisation? And, pray, what right have you to say that all but yourself are catering for the votes of the working men?... You may vaunt as much as you like your love for the "poor man"; there is one thing you dare not do... you dare not be an honest politician.[16]

An editorial on the Block system is in the Register, 16 March 1888: Taken at its best it seems to us that it is more a hindrance than of a help to the establishment of a sound and rational system of land tenure...[17] On 21 March a correspondent said: That he is sincere does not admit the question, but why the continual proclamations, why always clamour for the expected chorus of applause?...[18]

Two correspondents to the Register on 28 August 1888 pass judgement on Cotton: [It would be] much more worthy of a man who is privileged to write the prefix Honourable to his name if he were as particular in retailing slanderous statements...[19] You will have observed long ago that Cotton never gives a straightforward answer however called for by nasty innuendoes, falsehoods and misrepresentations which he slips into his communications...[20]

On industrial relations, Cotton wrote in the Register, 31 December 1889: I believe that the wage-receivers are quite as anxious for fair play as those who have to pay the wages. But who is to decide what is fair? Governments shirk the responsibility and cry delusively "It is a matter of open contract". and so it will remain... till it is realised that it is the function of every Government to be a great arbitration and conciliation Association – nothing more and nothing less. In the meantime Trades and Labour Councils must act for the workers...[21]

And on 10 February 1890 Cotton wrote in relation to parliamentary representation: What I hold is wanted is a fair representation of each class and not a packed chamber that can only legislate for the country from the standpoint of its own class interests... For several years past South Australia has progressed in one direction only and that is in rapidly adding to its indebtedness to foreigners...[22]

Death

Cotton died at his home on Young Street, Parkside after a brief and painful illness, leaving his widow, four sons, and a daughter.

An obituary is in the Register, 17 December 1892: Anything which tended to benefit the working classes received [his] most serious attention... There has been no man who has been more straight forward and endeavoured to do good in the community... The good acts of some men are far above their failings and [his] little faults could well be overlooked... The working men's block system [has] been a moral lesson to all the world... The tide of wealth had been heaped against him, but he had never shrunk from his duties.[23]

At his funeral, a wreath from some "blockers" bore the inscription – "In loving gratitude to [our] father, friend and champion"[24]

The Register of 3 February 1893 has a proposal for a "Cotton Memorial Homestead Institute" and at the same time the author unwittingly pens an appropriate epitaph for a man of compassion and Christian principles: He it was who trod that broader path of humanity, revelled in those broader views that teach us there is a temporal as well as a spiritual side to questions concerning man's salvation...[25]

Legacy

A school named after George Cotton was opened in 1914 and closed in 1945. The town of Cotton in the Hundred of Noarlunga is discussed in the Chronicle of 26 May 1894. The Block Scheme area of Cottonville in the southern suburbs of Adelaide was later re-subdivided and incorporated into Westbourne Park.

A house of Prince Alfred College Preparatory School was named after Cotton (and another after his father in law). The Cotton Memorial Hall in Mylor is named in his honour.

References

- Hirst, J. B. (1969). "Cotton, George Witherage (1821–1892)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- "The Late Hon. G. W. Cotton M.L.C." South Australian Register. 17 December 1892. p. 6. Retrieved 2 October 2014 – via Trove.

- "Type-Writing Machine". The Express and Telegraph. 7 September 1875. p. 2 – via Trove.

- "George Witherage Cotton". Former members of the Parliament of South Australia. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- Cotton, George W. (1888). Small Holdings, the Mainstay of Individuals and Nations. Adelaide.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)) - ""Mr Cotton and the Military" (the Chronicle, 25 June 1870)".

- "Delusive Demagogues". South Australian Register. 31 March 1886. p. 7. Retrieved 14 November 2022 – via Trove.

- "An apology". South Australian Register. 13 April 1886. p. 6. Retrieved 14 November 2022 – via Trove.

- "The Hon G. W. Cotton and the democracy". South Australian Register. 13 April 1886. p. 6. Retrieved 14 November 2022 – via Trove.

- "Mr. G. W. Cotton and Trades Unions". South Australian Register. 16 September 1886. p. 7. Retrieved 14 November 2022 – via Trove.

- "The savings bank". South Australian Register. 27 October 1886. p. 7. Retrieved 14 November 2022 – via Trove.

- "Fifty thousand homestead blocks". South Australian Register. 15 February 1888. p. 3. Retrieved 14 November 2022 – via Trove.

- "Rev. A. Honner's letter anent 50,000 blocks". South Australian Register. 17 February 1888. p. 7. Retrieved 14 November 2022 – via Trove.

- "Rev. A. Honner's letter anent 50,000 blocks". South Australian Register. 22 February 1888. p. 6. Retrieved 14 November 2022 – via Trove.

- "The sewating system". South Australian Register. 4 August 1890. p. 6. Retrieved 14 November 2022 – via Trove.

- "What are Mr. Cotton's views?". South Australian Register. 31 July 1888. p. 6. Retrieved 14 November 2022 – via Trove.

- "Working men's blocks". South Australian Register. 16 March 1888. p. 4. Retrieved 14 November 2022 – via Trove.

- "Working men's blocks". South Australian Register. 21 March 1888. p. 7. Retrieved 14 November 2022 – via Trove.

- "Henry George and the Hon G. W. Cotton". South Australian Register. 28 August 1888. p. 7. Retrieved 14 November 2022 – via Trove.>

- "A whimper from the Hon. G. W. Cotton". South Australian Register. 28 August 1888. p. 7. Retrieved 14 November 2022 – via Trove.

- "The workers". South Australian Register. 31 December 1889. p. 7. Retrieved 14 November 2022 – via Trove.

- "The parliament and the Adelaide club". South Australian Register. 10 February 1890. p. 6. Retrieved 14 November 2022 – via Trove.

- "The late Hon. G. W. Cotton M.L.C." South Australian Register. 17 December 1892. p. 6. Retrieved 14 November 2022 – via Trove.

- "The late Hon. G. W. Cotton". South Australian Register. 19 December 1892. p. 6. Retrieved 14 November 2022 – via Trove.

- "The Cotton Memorial Home Stead Institute". South Australian Register. 3 February 1893. p. 7. Retrieved 14 November 2022 – via Trove.

- Stent-Campbell, Linda (1998). "The Descendants of Richard Cotton". Retrieved 25 February 2008.

- The Manning Index of South Australian History, State Library of South Australia