Georgetown University Law Center

The Georgetown University Law Center is the law school of Georgetown University, a private research university in Washington, D.C., United States. It was established in 1870 and is the largest law school in the United States by enrollment and the most applied to,[5] receiving more full-time applications than any other law school in the country.[6][7]

| Georgetown University Law Center | |

|---|---|

| |

| Motto | Law is but the means — Justice is the end[1] |

| Parent school | Georgetown University |

| Religious affiliation | Roman Catholic (Jesuit) |

| Established | 1870 |

| School type | Private law school |

| Parent endowment | $1.661 billion[2] |

| Dean | William Treanor |

| Location | Washington, D.C., United States 38°53′54″N 77°0′45″W |

| Enrollment | 2,440: 1,982 JD, 441 LLM, 17 SJD |

| Faculty | 285: 126 full-time, 159 part-time |

| USNWR ranking | 15th (2023)[3] |

| Bar pass rate | 90.96%[4] |

| Website | www |

| ABA profile | Georgetown Law Profile |

The school's campus is several blocks from the U.S. Capitol Building, the center of the legislative branch of US government, and maintains a close association with the highest court in the US judicial branch, the nearby U.S. Supreme Court.[8]

Prominent alumni include 91 members of the United States Congress,[9] federal and state judges, billionaires, and diplomats. Georgetown is also ranked in the top 10 law schools for business and corporate law; international, criminal, environmental, health care, and tax law; as well as first in clinical training and part-time legal studies.[10]

History

Opened as Georgetown Law School in 1870, Georgetown Law was the second (after St. Louis University) law school run by a Jesuit institution within the United States.[11][12][lower-alpha 1] Georgetown Law has been separate from the main Georgetown campus (in the neighborhood of Georgetown) since 1890, when it moved near what is now Chinatown. The Law Center campus is located on New Jersey Avenue, several blocks north of the Capitol, and a few blocks west of Union Station. Georgetown Law School changed its name to Georgetown University Law Center in 1953.[13] The school added the Edward Bennett Williams Law Library in 1989 and the Gewirz Student Center in 1993, providing on-campus living for the first time. The "Campus Completion Project" finished in 2004 with the addition of the Hotung International Building and the Sport and Fitness Center.

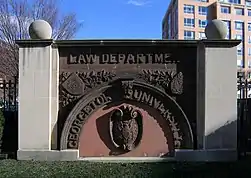

Georgetown Law's original wall (or sign) is preserved on the quad of the present-day campus.

Admissions

For the class entering in the fall of 2021, roughly 1,800 out of 14,052 J.D. applicants (12.9%) were offered admission, with 561 matriculating, marking the most competitive law school admission cycle and the largest applicant pool for any U.S. law school in history. The median LSAT score for the class entering in fall of 2021 is 171 and the median undergraduate GPA is 3.85. In the 2020–21 academic year, Georgetown Law had 2,021 J.D. students, of which 26% were minorities and 55% were female.[14]

Employment

Of the 691 J.D. graduates in the Georgetown Law class of 2020 (including both full- and part-time students), 569 (82.3%) held long-term, full-time positions that required bar exam passage (i.e., jobs as lawyers) and were not school-funded nine months after graduation.[16] 644 graduates overall (93.2%) were employed, 6 graduates (0.9%) were pursuing a graduate degree, and 34 graduates (4.9%) were unemployed.[16]

435 J.D. graduates (63.0%) were employed in the private sector, with 368 (53.3%) at law firms with over 250 attorneys.[16] 208 graduates (30.1%) entered the public sector, with 80 (11.6%) employed in public interest positions, 55 (8.0%) employed by the government, 68 (9.8%) in federal or state clerkships, and 5 (0.7%) in academic positions.[16] 35 graduates (5.1%) received funding from Georgetown Law for their positions.[16]

The median reported starting salary for a 2018 J.D. graduate in the private sector was $180,000. The median reported starting salary for a 2018 graduate in the public sector (including government, public interest, and clerkship positions) was $57,000.[17]

272 J.D. graduates (39.4%) in the class of 2020 were employed in Washington, DC, 155 (22.4%) in New York, and 31 (4.5%) in California. 13 (1.9%) were employed outside the United States.[16]

As of 2011, Georgetown Law alumni account for the second highest number of partners at NLJ 100 firms. It is among the top ten feeder schools in eight of the ten largest legal markets in the United States by law job openings (New York, Washington DC, Chicago, Los Angeles, Boston, Houston, San Francisco, and San Diego), again giving it the second-widest reach of all law schools. The school performs especially strongly in its home market, where it is the largest law school and has produced the greatest number of NLJ 100 partners.[18]

Georgetown Law was ranked #11 for placing the highest percentage of 2018 J.D. graduates into associate positions at the 100 largest law firms.[19]

Costs

The total cost of attendance (indicating the cost of tuition, fees, and living expenses) at Georgetown Law for the 2021–2022 academic year is $99,600.[20] The Law School Transparency estimated debt-financed cost of attendance for three years is $352,279.[21]

Campus

The Law Center is located in the Capitol Hill area of Washington, D.C. It is bounded by 2nd St. NW to the west, E St. NW to the south, 1st St. NW and New Jersey Avenue to the east, and Massachusetts Avenue to the north.

The campus consists of five buildings. Bernard P. McDonough Hall (1971, expanded in 1997) houses classrooms and Law Center offices and was designed by Edward Durell Stone. The Edward Bennett Williams Law Library building (1989) houses most of the school's library collection and is one of the largest law libraries in the United States. The Eric E. Hotung International Law Center (2004), named after Hong Kong businessman and philanthropist Eric Edward Hotung, includes two floors of library space housing the international collection, and also contains classrooms, offices, and meeting rooms. The Bernard S. and Sarah M. Gewirz Student Center (1993) provides apartment-style housing for 250–300 students as well as hosting offices for nine academic centers and institutes, the Law Center's Student Health clinic, the Center for Wellness Promotion, the Counseling and Psychiatric Service office, a dedicated prayer room for Muslim members of the Law Center community, a moot court room, a daycare (the Georgetown Law Early Learning Center), and a ballroom event space commonly used for academic conferences. The four-level Scott K. Ginsburg Sport & Fitness Center (2004) includes a pool, fitness facilities, and cafe, and connects the Hotung Building to the Gewirz Student Center.

Libraries

The Georgetown Law Library supports the research and educational endeavors of the students and faculty of the Georgetown University Law Center. It is the second largest law library in the United States, and as one of the premier research facilities for the study of law, the Law Library houses the nation's fourth largest law library collection and offers access to thousands of online publications. The Law Library was ranked by The National Jurist as the 14th best law library in the nation in 2010.[22]

The mission of the library is to support fully the research and educational endeavors of the students and faculty of the Georgetown University Law Center, by collecting, organizing, preserving, and disseminating legal and law related information in any form, by providing effective service and instructional programs, and by utilizing electronic information systems to provide access to new information products and services.

The collection is split into two buildings. The Edward Bennett Williams Law Library (1989) is named after Washington, D.C. lawyer Edward Bennett Williams, an alumnus of the Law Center and founder of the prestigious litigation firm Williams & Connolly. It houses the Law Center's United States law collection, the Law Center Archives, and the National Equal Justice Library. The Williams library building consists of five floors of collection and study space and provides office space for most of the Law Center's law journals on the Law Library's first level.

The John Wolff International and Comparative Law Library (2004) is named after John Wolff, a long-serving member of the adjunct faculty and supporter of the Law Center's international law programs. The library is located on two floors inside the Eric E. Hotung building. It houses the international, foreign, and comparative law collections of the Georgetown University Law Center. Wolff Library collects primary and secondary law materials from Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Great Britain, Ireland, Mexico, New Zealand, Scotland, and South Africa. English translations of primary and secondary legal materials from other jurisdictions and compilations of foreign law on special topics are also included.

In addition to foreign law, the Wolff Library maintains an extensive collection of public and private international law, focusing on international trade, international environmental law, human rights, arbitration, tax and treaty law. The collection also includes documentation from many international organizations, including the International Court of Justice, the United Nations, the European Union, and the World Trade Organization.

Curriculum

Georgetown Law's J.D. program can be completed over three years of full-time day study or three to four years of part-time evening study. The school offers several LL.M. programs in specific areas, most notably tax law, as well as a general LL.M. curriculum for lawyers educated outside the United States. Georgetown launched a Master of Studies in Law (M.S.L.) degree program for professional journalists in the 2007–08 academic year. It also offers the highest doctoral degree in law (J.S.D.).

Students are offered the choice of two tracks for their first year of study. "Curriculum A" is a traditional law curriculum similar to that taught at most schools, including courses in civil procedure, constitutional law, contracts, criminal justice, property, torts, and legal research and writing. Four-fifths of the day students at Georgetown receive instruction under the standard program (sections 1, 2, 4, and 5).

"Curriculum B" is a more interdisciplinary, theoretical approach to legal study, covering an equal or wider scope of material but heavily influenced by the critical legal studies movement. The Curriculum B courses are Bargain, Exchange and Liability (contracts and torts), Democracy and Coercion (constitutional law and criminal procedure), Government Processes (administrative law), Legal Justice (jurisprudence), Legal Practice (legal research and writing), Legal Process and Society (civil procedure), and Property in Time (property). One-fifth of the full-time JD students receive instruction in the alternative Curriculum B program (Section 3).

Students in both curricula may participate in a week-long introduction to international law between the fall and spring semesters.

Clinics / programs

Georgetown has long been nationally recognized for its leadership in the field of clinical legal education. In 2018, U.S. News ranked Georgetown #1 in the nation for Clinical Training, followed by New York University (2nd), CUNY (3rd), American University (4th), and Yale University (5th).[23] Over 300 students typically participate in the program.

Georgetown's clinics are: Appellate Litigation Clinic, Center for Applied Legal Studies, The Community Justice Project, Criminal Defense & Prisoner Advocacy Clinic, Criminal Justice Clinic, D.C. Law Students in Court, D.C. Street Law Program, Domestic Violence Clinic, Federal Legislation and Administrative Clinic, Harrison Institute for Housing & Community Development Clinic, Harrison Institute for Public Law, Institute for Public Representation, International Women's Human Rights Clinic, and Juvenile Justice Clinic.

In the Winter 2017 edition of The National Jurist, Georgetown Law's Moot Court Program was ranked #4 in the country for 2015–16 and #5 among U.S. law schools that have had the best moot courts this past decade.[24]

Appellate Litigation Clinic

Directed by Professor Erica Hashimoto (following 36 years of leadership by Professor Steven H. Goldblatt), the Appellate Litigation Clinic operates akin to a small appellate litigation firm. It has had four cases reach the United States Supreme Court on grants of writs of certiorari.[25] One such case was Wright v. West, 505 U.S. 277 (1992), considered in habeas corpus the question whether the de novo review standard for mixed questions of law and fact established in 1953 (the Brown v. Allen standard) should be overruled. Another was Smith v. Barry, 502 U.S. 244 (1992), which reversed a Fourth Circuit determination that the court did not have jurisdiction over an appeal because the defendant's pro se brief could not serve as a timely notice of appeal.

Center for Applied Legal Studies

CALS represents refugees seeking political asylum in the United States because of threatened persecution in their home countries. Students in CALS assume primary responsibility for the representation of these refugees, whose requests for asylum have already been rejected by the U.S. government.[26] The Center for Applied Legal Studies was founded in the 1980s by Philip Schrag.[27] Until 1995, the Clinic heard cases in the field of consumer protection. Under the direction of Schrag and Andrew Schoenholtz, the Clinic began specializing in asylum claims, for both detained and non-detained applicants.[28] In conjunction with their work for the Clinic, Schrag and Schoenholtz have written books about America's political asylum system, with the help of Clinic fellows and graduate students. The duo's most recent book, Lives in the Balance, was published in 2014 and provides an empirical analysis of how Homeland Security decided asylum cases over a recent fourteen-year period.[29] The group's work in human rights law has met praise from international organizations like the United Nations Human Rights Council.[30] Under the direction of Schrag and Schoenholtz, the clinic has also focused on more prolonged displacement situations for political refugees.[31]

Civil Rights Clinic

CRC operates as a public interest law firm, representing individual clients and other public interest organizations, primarily in the areas of discrimination and constitutional rights, workplace fairness, and open government.[32] The Clinic is directed by Professor Aderson Francois, who joined in 2016.[33] Students work with CRC staff attorneys to litigate Freedom of Information Act claims, wage theft suits, and retaliation claims on behalf of employees terminated for asserting their rights under FLSA and DC Wage and Hour law.

Criminal Defense and Prisoner Advocacy Clinic

Students in CDPAC represent defendants facing misdemeanor charges in D.C. Superior Court, facing parole or supervised release revocation from the United States Parole Commission working with the Public Defender Service for the District of Columbia, and they also work on prisoner advocacy projects.[34] Abbe Smith is the director of CDPAC.[35] Former Public Defender Service for the District of Columbia lawyer Vida Johnson works with Smith in CDPAC and the Prettyman fellowship program.[36]

DC Street Law Program

The DC Street Law Program, Directed by Professor Charisma X. Howell, provides legal education to the DC population through two projects: the Street Law High Schools Clinic and the Street Law Community Clinic. Professor Richard Roe directed the Street Law High Schools Clinic since 1983. Professor Howell became the director in 2018. In the program, students introduce local high school students to the basic structure of the legal system, including the relationship among legislatures, courts, and agencies, and how citizens, especially in their world, relate to the lawmaking processes of each branch of government.[37][38]

Harrison Institute for Public Law

The Harrison Institute is one of the longest running public law clinics in the country, having begun as the Project for Community Legal Assistance in 1972. In 1980 it was renamed in honor of Anne Blaine Harrison, a philanthropist and early supporter of the institute.[39] Over its history, the institute has been home to several clinical programs, including focuses on state and local legislation, administrative advocacy, housing and community development, and policy. In 2019, under the directorship of Robert Stumberg, the institute consists of four policy teams: Climate, Health, Human Rights, and Trade.[40] Each of these teams involves students working to shape policy to achieve client goals.

Publications

Georgetown University Law Center publishes fourteen student-run law journals, two peer-reviewed law journals, and a weekly student-run newspaper, the Georgetown Law Weekly. The journals are:

- American Criminal Law Review

- Food and Drug Law Journal[41]

- Georgetown Environmental Law Review

- Georgetown Immigration Law Journal

- Georgetown Journal of Gender and the Law

- Georgetown Journal of International Law

- Georgetown Journal of Law and Modern Critical Race Perspectives

- Georgetown Journal of Law and Public Policy

- Georgetown Journal of Legal Ethics

- Georgetown Journal on Poverty Law and Policy

- Journal of National Security Law and Policy[42]

- Georgetown Law Technology Review (online only)[43][44][45][46][47][48]

- Georgetown Law Journal

- In 2021, ranked by Google Scholar and Washington and Lee School of Law as the #4 and #5 most influential law review in the country, respectively.[49]

- In 2021, ranked #8 in the nation based on the Meta Ranking of Flagship US Law Reviews at U.S. law schools by Assistant Professor Bryce Clayton Newell.[50]

Controversies

In January 2022, Ilya Shapiro, the incoming executive director and senior lecturer of the Georgetown Center for the Constitution, wrote in a tweet that he opposed President Biden's intent to nominate a black woman to the Supreme Court, writing that because Biden would not nominate Shapiro's friend Sri Srinivasan, he was choosing a "lesser black woman."[51] The dean of Georgetown University Law Center condemned the remarks, stating, "The tweets’ suggestion that the best Supreme Court nominee could not be a Black woman and their use of demeaning language are appalling...The tweets are at odds with everything we stand for at Georgetown Law." Shapiro later deleted the tweet as well as many other tweets he had written in the past, and issued a statement calling it an, "inartful tweet."[52] Shapiro was then placed on administrative leave while being investigated for violations of "professional conduct, non-discrimination, and anti-harassment" rules.[53] As a result of the investigation, Shapiro was reinstated, as the school's investigators found that he was "not properly subject to discipline."[54] Nevertheless, on June 6 Shapiro chose to resign in protest, arguing that the school had "implicitly repealed Georgetown’s vaunted Speech and Expression Policy and set me up for discipline the next time I transgress progressive orthodoxy."[55]

List of deans

| No. | Name | Years | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vice Presidents of the Law Department[56] | |||

| 1 | Charles P. James | 1870–1873 | [57] |

| 2 | George W. Paschal | 1873–1875 | [57] |

| Deans of Georgetown Law School | |||

| 3 | Charles W. Hoffman | 1876–1890 | [57] |

| 4 | Martin Ferdinand Morris | 1889–1890 | [58] |

| 5 | George E. Hamilton | 1900–1903 | [58] |

| 6 | Harry M. Clabaugh | 1903–1914 | [58] |

| 7 | George E. Hamilton | 1914–1941 | [58] |

| 8 | Hugh J. Fegan | 1941–1953 | [58] |

| Deans of the Georgetown University Law Center | |||

| - | Hugh J. Fegan | 1953–1955 | [58] |

| 9 | Paul R. Dean | 1955–1969 | [58] |

| 10 | Adrian S. Fisher | 1969–1976 | [59] |

| 11 | David J. McCarthy Jr. | 1976–1983 | [59] |

| 12 | Robert Pitofsky | 1983–1989 | [59] |

| 13 | Judith Areen | 1989–2004 | [59] |

| 14 | T. Alexander Aleinikoff | 2004–2010 | [59] |

| 15 | William Treanor | 2010–present | [60] |

Faculty

Notable current faculty include:

- Charles F. Abernathy, Professor of civil rights and comparative law

- Lama Abu-Odeh, Palestinian-American scholar of Islamic law, family law, and feminism

- Randy Barnett, Libertarian constitutional law scholar, author of The Structure of Liberty and Restoring the Lost Constitution, 2008 Guggenheim Fellow

- M. Gregg Bloche, professor of public health policy

- Rosa Brooks, Professor of national security, military, and international law, columnist for Foreign Policy

- Paul Butler, Professor of criminal law and civil rights, expert on jury nullification

- Sheryll D. Cashin, Professor of civil rights and housing law

- Julie E. Cohen, Professor of copyright, intellectual property, and privacy law

- David D. Cole, Professor of first amendment and criminal procedure law

- Peter Edelman, former Assistant Secretary of Health and Human Services

- Doug Emhoff, Distinguished Visitor from Practice, Distinguished Fellow of Georgetown Law's Institute for Technology Law and Policy, Second Gentleman of the United States, Entertainment Lawyer

- Heidi Li Feldman, Professor of law

- Lawrence O. Gostin, Professor of public health law

- Shon Hopwood, Associate Professor, convicted bank robber turned jailhouse lawyer who represented matters before the Supreme Court

- Neal Katyal, Former Acting Solicitor General of the United States, Professor of national security law

- Marty Lederman, Associate Professor, Deputy Assistant Attorney General at the Department of Justice Office of Legal Counsel

- Naomi Mezey, Professor of law and culture

- Eleanor Holmes Norton, Delegate representing Washington, DC in the U.S. House of Representatives

- Victoria F. Nourse, Chief Counsel to Vice President Joe Biden and principal author of the Violence Against Women Act

- Ladislas Orsy, canonical theologian

- Gary Peller, Prominent member of critical legal studies and critical race theory movements

- Nicholas Quinn Rosenkranz, former attorney-advisor at the Office of Legal Counsel in the U.S. Department of Justice

- Louis Michael Seidman, Carmack Waterhouse Professor of Constitutional Law, significant proponent of the critical legal studies movement

- Howard Shelanski, Former Administrator of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs

- Abbe Smith, Criminal Defense Attorney and Director of the Criminal Defense & Prisoner Advocacy Clinic

- Daniel K. Tarullo, Member of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

- William M. Treanor, Dean of Georgetown University Law Center, former dean of Fordham University School of Law, noted constitutional law expert

- Rebecca Tushnet, Professor of copyright, trademark, intellectual property, and first amendment law, noted for her scholarship on fanfiction

- David Vladeck, Former Director of the Bureau of Consumer Protection at the Federal Trade Commission

- Edith Brown Weiss, Professor of international law and former president of the American Society of International Law

- Robin West, Frederick J. Haas Professor of Law and Philosophy, proponent of feminist legal theory and the law and literature movement

Notable alumni

Notes

- Although information provided on Georgetown Law's website claims when they were founded in 1870, the school was the first law school in the United States instituted by a Jesuit run institution. This is simply untrue however, as the also Jesuit run St. Louis University opened a law school decades earlier, in 1843. It is not clear how or why officials from Georgetown came to believe otherwise.

References

Citations

- Expressed by Joseph A. Cantrel (Class of 1922), at the 50th Anniversary Celebration in December 1920. See official site Archived July 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- As of June 30, 2017. "U.S. and Canadian Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year (FY) 2017 Endowment Market Value and Change in Endowment Market Value from FY 2016 to FY 2017" (PDF). National Association of College and University Business Officers and Commonfund Institute. 2017. Archived from the original on February 26, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "US News Law School Rankings".

- "School Detail Information". lsac.org.

- 125th Anniversary – Georgetown Law Library, Georgetown University Law Center, Retrieved: January 30, 2017

- 10 Law Schools With the Most Full-Time Applications, U.S. News & World Report, Published: March 31, 2016. Retrieved: January 30, 2017

- Strauss, Valerie (November 13, 2021). "The country's most popular law school got an unexpected jolt". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved October 3, 2022.

- "Visit Our Campus". www.law.georgetown.edu. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- "Eleven Georgetown Law Alumni Will Serve in the 117th Congress". Retrieved January 5, 2021.

- "USNWR Law School Rankings: Georgetown University". usnews.com. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- "Timeline of Saint Louis University". https://www.slu.edu/timeline/ Saint Louis University. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- "About". www.law.georgetown.edu. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- Curran 2010b, p. 311

- "2020 Standard 509 Information Report" (PDF). American Bar Association. Retrieved December 12, 2020.

- "Employment Summary for 2020 Graduates" (PDF).

- "American Bar Association Employment Summary for 2020 Graduates – Georgetown Law" (PDF). Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- "Georgetown University Law Center Class of 2018 Summary Report" (PDF). Retrieved November 15, 2020.

- Theodore P. Seto (2011). "Where Do Partners Come From?". Journal of Legal Education. SSRN 1903934.

- "Sneak Peek at the 2019 Go-To Law Schools: Nos. 11–20 | Law.com". Law.com. Retrieved April 17, 2019.

- "Tuition & Cost of Attendance". www.law.georgetown.edu.

- "Georgetown University, Finances". www.lstreports.com.

- "Best Law Libraries | the National Jurist". www.nationaljurist.com. October 12, 2010. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- "Best Law Schools; US News Best Graduate Schools". Retrieved April 2, 2018.

- "The National Jurist – Winter 2017". www.nxtbook.com. Retrieved May 11, 2018.

- "Appellate Litigation Clinic — Georgetown Law". Law.georgetown.edu. October 14, 2014. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- "Center for Applied Legal Studies — Georgetown Law". Law.georgetown.edu. October 14, 2014. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- "Faculty Receive Prestigious Medals as Presidential Fellows at Convocation | Georgetown University". Georgetown.edu. October 15, 2014. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- Prof, Immigration. "ImmigrationProf Blog". Lawprofessors.typepad.com. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- "Lives in the Balance | Asylum Adjudication by the Department of Homeland Security | Books". NYU Press. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- Schoenholtz, Andrew I. (2005). "Refugee Protection in the United States Post-September 11". Georgetown University Law Center.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Wong, Edward. ""The New Refugees and the Old Treaty: Persecutors and Persecuted in the Twenty-First Century" by Schoenholtz, Andrew I. – Chicago Journal of International Law, Vol. 16, Issue 1, Summer 2015". Archived from the original on September 27, 2015.

- Georgetown University Law Center. "Civil Rights Clinic".

- Georgetown University Law Center. "Fellowships".

- "Criminal Defense & Prisoner Advocacy Clinic (CDPAC)". law.georgetown.edu.

- "Profile Abbe Smith". law.georgetown.edu.

- "CDPAC Staff". georgetown.law.edu.

- "About Our Clinic — Georgetown Law". Law.georgetown.edu. October 14, 2014. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- "Street law schools in life skills – Video on". Nbcnews.com. August 3, 2012. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- "The Anne Blaine Harrison Institute". The Washington Post. May 5, 1978. Retrieved October 9, 2019.

- "Harrison Institute for Public Law". law.georgetown.edu.

- "Food and Drug Law Journal".

- "Journal of National Security Law & Policy". jnslp.com.

- "Georgetown Law Technology Review". georgetownlawtechreview.org.

- "Privacy Policy". Georgetown Law Technology Review. November 17, 2016. Retrieved July 18, 2022.

- "Georgetown Law Tech Review: Symposium 2022". Georgetown University Law Center. Retrieved July 18, 2022.

- "Georgetown Law Technology Review". Georgetown University Law Center. Retrieved July 18, 2022.

- "Georgetown Law Technology Review Student Writing Competition". University of Georgia School of Law. University of Georgia. Retrieved July 18, 2022.

- "About Us". Georgetown Law Technology Review. September 9, 2016. Retrieved July 18, 2022.

- "2021 Meta Rankings". Meta Rankings. Retrieved December 3, 2021.

- "Law Journal Ranking – Bryce Clayton Newell". Law Journal Meta. Retrieved December 3, 2021.

- Ma, Alexandra. "Incoming Georgetown Law professor prompts backlash by saying Biden will pick 'lesser Black woman' for Supreme Court". Business Insider. Retrieved January 29, 2022.

- "Incoming Georgetown Law administrator apologizes after tweets dean called 'appalling'". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved January 29, 2022.

- "Tweet by Mark Joseph Stern of Slate Magazine". Twitter. Retrieved January 31, 2022.

- Lumpkin, Lauren. "Georgetown Law official cleared over tweets on Supreme Court pick". Washington Post. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- Lumpkin, Lauren. "Georgetown Law official resigns, had been cleared in probe into tweets". Washington Post. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- "Georgetown Law Timeline". Georgetown University Law Center. Archived from the original on August 26, 2022. Retrieved October 6, 2022.

- Curran 2010a, p. 367, Appendix D: Presidents, Prefects, and Deans in Georgetown's First Century

- Curran 2010b, p. 401, Appendix F: Deans of the Law School, 1889–1969

- Curran 2010c, p. 294, Appendix F: Deans of the Law School/Executive Vice Presidents for Law Center Affairs, 1955–2010

- "William M. Treanor is Reappointed as Dean of Georgetown Law". Georgetown University Law Center. June 15, 2020. Archived from the original on July 4, 2022. Retrieved October 6, 2022.

Sources

- Curran, Robert Emmett (2010a). A History of Georgetown University, From Academy to University, 1789—1889. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press. ISBN 978-1-58901-689-7.

- Curran, Robert Emmett (2010b). A History of Georgetown University: The Quest for Excellence, 1889–1964. Vol. 2. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press. ISBN 978-1-58901-689-7.

- Curran, Robert Emmett (2010c). A History of Georgetown University: The Rise to Prominence, 1964—1989. Vol. 3. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press. ISBN 978-1-58901-691-0.

External links

- Official website

- INSPIRE records, at the University of Maryland libraries. The Institute of Public Interest Representation (INSPIRE) is part of the Georgetown University Law Center.