Germanic law

Germanic law is a scholarly term used to describe a series of commonalities between the various law codes (the Leges Barbarorum, 'laws of the barbarians', also called Leges) of the early Germanic peoples. These were compared with statements in Tacitus and Caesar as well as with high and late medieval law codes from Germany and Scandinavia. Until the 1950s, these commonalities were held to be the result of a distinct Germanic legal culture. Scholarship since then has questioned this premise and argued that many "Germanic" features instead derive from provincial Roman law. Although most scholars no longer hold that Germanic law was a distinct legal system, some still argue for the retention of the term and for the potential that some aspects of the Leges in particular derive from a Germanic culture.[1][2][3]

While the Leges Barbarorum were written in Latin and not in any Germanic vernacular, codes of Anglo-Saxon law were produced in Old English. The study of Anglo-Saxon and continental Germanic law codes has never been fully integrated.[4]

Existence and controversy

The concept of "Germanic law" arose in the modern period, at a time when scholars thought that the written and unwritten principles of the ancient Germanic peoples could be reconstructed in a reasonably coherent form.[5] The term leges barbarorum, 'laws of the barbarians', used by editor Paolo Canciani as early as 1781, reflects a negative value judgement on the actual law codes produced by these Germanic peoples. It was retained by the editors of the Monumenta Germaniae Historica in the 19th century.[6]

Until the middle of the 20th century, the majority of scholars assumed the existence of a distinct Germanic legal culture and law. This law was seen as an essential element in the formation of modern European law and identity, alongside the Roman law and canon law.[7] Scholars reconstructed Germanic law on the basis of antique (Caesar and Tacitus), early medieval (mainly the so-called Leges Barbarorum, laws written by various continental Germanic peoples from the fifth to eighth centuries),[8] and late medieval sources (mostly Scandinavian).[9] According to these scholars, Germanic law was based on a society ruled by assemblies of free farmers (the things), policing themselves in clan groups (sibbs), and engaging in the blood feud outside of clan groups, which could be ended by the payment of compensation (wergild). This reconstructed legal system also excluded certain criminals by outlawry, and had a form of sacral kingship; retinues formed around the kings bound by oaths of loyalty.[10]

Early ideas about Germanic law have come under intense scholarly scrutiny since the 1950s, and specific aspects of it such as the legal importance of sibb, retinues, and loyalty, and the concept of outlawry can no longer be justified.[11][12] Besides the assumption of a common Germanic legal tradition and the use of sources of different types from different places and time periods,[11] there are no native sources for early Germanic law. Caesar and Tacitus do mention some aspects of Germanic legal culture that reappear in later sources, however their texts are not objective reports of facts and there are no other antique sources to corroborate whether these are common Germanic institutions.[13][14] Reinhard Wenskus has shown that one important "Germanic" element, the use of popular assemblies, displays marked similarities to developments among the Gauls and Romans, and was therefore likely the result of external influence rather than specifically Germanic.[15] Even the Leges Barbarorum were all written under Roman and Christian influence and often with the help of Roman jurists.[16] Additionally, the Leges contain large amounts of "Vulgar Latin law", an unofficial legal system that functioned in the Roman provinces, so that it is difficult to determine whether commonalities between them derive from a common Germanic legal conception or not.[17]

Although Germanic law never appears to have been a competing system to Roman law, it is possible that Germanic "modes of thought" (Denkformen) still existed, with important elements being an emphasis on orality, gesture, formulaic language, legal symbolism, and ritual.[18] Gerhard Dilcher defends the notion of Germanic law by noting that the Germanic peoples clearly had law-like rules that they, under the influence of Rome, began to write down and used to define aspects of their identity. The process was nevertheless the result of a cultural synthesis.[1] Daniela Fruscione similarly argues that early medieval law shows many features that might be called "new archaic", and can conveniently be called Germanic, even though other peoples may have contributed aspects of them.[2] Some items in the Leges, such as the use of vernacular words, may reveal aspects of originally Germanic, or at least non-Roman, law. Legal historian Ruth Schmidt-Wiegand writes that this vernacular, often in the form of Latinized words, belongs to "the oldest layers of a Germanic legal language" and shows some similarities to Gothic.[19][3]

Elements

The Assembly

In common with many archaic societies without a strong monarchy,[20] early Germanic law appears to have had a form of popular assembly. According to Tacitus, during the Roman period, such assemblies were called at the new or full moon and were where important decisions were made (Tacitus, Germania 11–13).[21] Germanic assemblies functioned both to make important political decisions—or to legitimate decisions taken by rulers—as well as functioning as courts of law.[22] The Leges Alamannorum specified that all free men were required to appear at a popular assembly, but such a specification is otherwise absent for the Frankish Merovingian period.[23] In later periods outside Scandinavia, the assemblies were composed of important persons rather than the entire free population.[24] The Visigothic laws lack any mention of a popular assembly,[25] while the Anglo-Saxon laws and history show no evidence of any kingdom-wide popular assemblies, only smaller local or regional assemblies held under various names.[26]

The earliest term for these assemblies in Germanic is the thing,[lower-alpha 1] which is first attested on a votive altar at Hadrian's Wall dedicated to "Mars Thingsus" ("Mars of the Thing") from the third century. The earliest use of the term in a Germanic language is from Old High German (thing) and Old English (ðing), however, by this time it had already begun to have a more general use than as the name of the assembly.[28] The use of thing as an epithet in the name "Mars Thingsus", apparently referring to the Germanic god Tyr, as well as the translation of the Roman dies Martii ("day of Mars", Tuesday) as dingsdag ("day of the thing", modern German Dienstag) as a variant of tîsdag ("day of Tyr"), has led to the theory that the thing stood under the protection of Tyr in pagan times.[29]

In the Lex Salica and laws influenced by it, the Latinized vernacular term mallus or mallum[lower-alpha 2] is used to refer to the assembly, a usage continued through the Carolingian period: the mallus functioned as a regular court and met for three days every forty or forty-two nights at a location known as the mallobergus.[31] In the Carolingian period, the mallus became a court under the control of a count rather than a popular court.[32]

Germanic legal language

Germanic legal vocabulary is reconstructed from multiple sources, including early loanwords in Finnic languages, supposed translations of Germanic terms in Tacitus, apparently legal terms in the Gothic Bible, elements in Germanic names, Germanic words found in the Leges barbarorum, as well as in later vernacular legal texts, beginning with Old English (7th-9th centuries).[33] However, there is no evidence for a shared Proto-Germanic legal terminology; rather the individual languages show a diversity of legal terminologies, with the earliest examples lacking even a common Germanic word for "law".[34]

A word attested meaning "law" as well as "religion" in West Germanic languages is represented by Old High German êwa;[lower-alpha 3] there is some evidence for the word's existence from names preserved in Old Norse and Gothic.[36] Êwa is used in the Latin texts of the Leges barbaroum to mean the unwritten laws and customs of the people, but comes also to refer to the codified written laws as well.[37] Jacob Grimm argued that Êwa's use to also mean "religion" meant there was also a religious dimension to pre-Christian Germanic law;[38] Ruth Schmidt-Wiegand argues instead that the legal term êwa was given a Christian religious significance by Christian missionaries, in common with other legal terms that lacked any pagan religious significance that acquired Christian meanings.[39]

Marriage

Modern scholarship no longer posits a common Germanic marriage practice,[40] and there is no common Germanic term for "marriage".[41] Until the latter 20th century, legal historians, using the Leges and later Norse narrative and legal sources, divided Germanic marriages into three types:

- Muntehe, characterized by a marriage treaty, the granting of a bride gift or morning gift to the bride, and the acquisition of munt (mundium in the Lombard Laws, meaning "protection", originally "hand"),[42] or legal power, of the husband over the wife;[43]

- Friedelehe, (from Old High German: friudila, Old Norse: friðla, frilla "beloved"), a form of marriage lacking a bride or morning gift and in which the husband did not have munt over his wife (this remained with her family);[44]

- Kebsehe (concubinage), the marriage of a free man to an unfree woman.[44]

According to this theory, in the course of the early Middle Ages, the Friedelehe, Kebsehe, and polygamy were abolished in favor of the Muntehe through the attacks of the Church.[45][46]

None of the three forms of marriage posited by older scholarship appear as such in medieval sources.[47] Academic works in the 1990s and 2000s rejected the notion of Friedelehe as a construct for which no evidence is found in the sources,[48] while Kebsehe has been explained as not being a form of marriage at all.[49]

Compensatory justice

All of the Leges contain catalogues of compensation prices to be paid by the perpetrator to his victims or the victim's relatives for committing a crime.[50] In the West Germanic languages, this payment is known by the term Old High German: buoza, Old English: bōta.[51] This form of legal reconciliation aimed to prevent the erupting of feuds by offering a peaceful way to end disputes between groups.[52] The creation of these catalogues was encouraged by the kings of the individual Germanic kingdoms, who had an interest in preventing bloodshed. Some of the laws, such as the Lex Salica and the Lex Thuringiorum, require that part of the compensation for theft be paid to the king. Later, some kings attempted to replace the compensation system with other forms of justice, such as the death penalty.[53]

In the event that a person was killed or wounded, or an animal was stolen, the compensation is referred to as wergild.[lower-alpha 4] It is unclear if wergild was a traditional Germanic concept, or if it developed from a Roman predecessor.[55] Different Leges handle wergild differently: the Lex Burgundonum and the Lex Alamannorum split free persons in various categories, while the Lex Salica treats all free persons alike.[56] The prices were in most cases higher than could readily be paid, forcing the parties to a compromise. Payment was most likely taken in kind rather than in currency.[57]

The Leges barbarorum

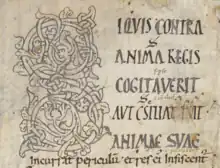

The Leges barbarorum are the product of a mixture of Germanic, late Roman, and early Christian legal cultures.[58] The law codes are written in Latin, often using many Latinized Germanic terms, with the exception of the Anglo-Saxon law codes, which were written in the vernacular as early as the sixth century.[8] The Germanic peoples associated with the laws were not homogenous ethnic or linguistic groups in the modern sense.[59]

The earliest of these law codes dealt with Germanic groups living either as foederati or conquerors among Roman people and regulating their relationship to them.[60] These earliest codes, written by Visigoths in Spain (475),[lower-alpha 5] were probably not intended to be valid solely for the Germanic inhabitants of these kingdoms, but for the Roman ones as well.[62][63] These earliest law codes influenced those that followed, such as the Burgundian Lex Burgundionum (between 480 and 501) issued by king Gundobad, and the Frankish Lex Salica (between 507 and 511), possibly issued by Clovis I. The final law code of this earliest series of codifications was the Edictus Rothari, issued in 643 by the Lombard King Rothari.[60][64] Generally speaking, the further on the periphery of the Roman Empire these law codes were issued, the less influence they appear to show from Roman jurisprudence.[65]

| law code | people | issuer | Year of completion / approval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Code of Euric | Visigoths | Euric | c. 480 |

| Lex Burgundionum | Burgundians | Gundobad | c. 500 |

| Lex Salica | Salian Franks | Clovis I | c. 500 |

| Pactus Alamannorum | Alamanni | c. 620 | |

| Lex Ripuaria | Ripuarian Franks | 630s | |

| Edictum Rothari | Lombards | Rothari | 643 |

| Lex Visigothorum | Visigoths | Recceswinth | 654 |

| Lex Alamannorum | Alamanni | 730 | |

| Lex Bajuvariorum | Bavarians | c. 745 | |

| Lex Frisionum | Frisians | Charlemagne | c. 785 |

| Lex Saxonum | Saxons | Charlemagne | 803 |

| Lex Angliorum et Werinorum, hoc est, Thuringorum | Charlemagne | 9th century |

Visigothic law codes

Compared with other barbarian tribes, the Goths had the longest time of contact with Roman civilization, from migration in 376 to trade interactions years beforehand. The Visigothic legal attitude held that laws were created as new offenses of justice arose, and that the king's laws originated from God and His justice-scriptural basis.[66] Mercifulness (clementia) and a paternal feeling (pietas) were qualities of the king exhibited through the laws.[67] The level of severity of the law was "tempered" by this mercy, specifically for the poor; it was thought that by showing paternal love in formation of law, the legislator gained the love of citizen.[68] While the monarch's position was implicitly supreme and protected by laws, even kings were subject to royal law, for royal law was thought of as God's law.[69] In theory, enforcement of the law was the duty of the king, and as the sovereign power he could ignore previous laws if he desired, which often led to complications.[70] To regulate the king's power, all future kings took an oath to uphold the law.[71] While the Visigoths' law code reflected many aspects of Roman law, over time it grew to define a new society's requirements and opinions of law's significance to a particular people.

It is certain that the earliest written code of the Visigoths dates to Euric (471). Code of Euric (Codex Euricianus), issued between 471 and 476, has been described as "the best legislative work of the fifth century".[72] It was created to regulate the Romans and Goths living in Euric's kingdom, where Romans greatly outnumbered Goths. The code borrowed heavily from the Roman Theodosian Code (Codex Theodosianus) from the early fifth century, and its main subjects were Visigoths living in Southern France.[73] It contained about 350 clauses, organized by chapter headings; about 276 to 336 of these clauses remain today. Besides his own constitutions, Euric included in this collection the unwritten constitutions of his predecessors Theodoric I (419-451), Thorismund (451-453), and Theodoric II (453-466), and he arranged the whole in a logical order. Of the Code of Euric, fragments of chapters 276 to 337 have been discovered in a palimpsest manuscript in the Bibliothèque Nationale at Paris (Latin coll, No. 12161), proving that the code ran over a large area. Euric's code was used for all cases between Goths, and between them and Romans; in cases between Romans, Roman law was used.[74]

At the insistence of Euric's son, Alaric II, an examination was made of the Roman laws in use among Romans in his dominions, and the resulting compilation was approved in 506 at an assembly at Aire, in Gascony, and is known as the Breviary of Alaric, and sometimes as the Liber Aniani, from the fact that the authentic copies bear the signature of the referendarius Anian.[74] In 506 CE, Alaric II, son of Euric, assembled the council of Agde to issue the Breviary of Alaric (Lex Romana Visigothorum), applying specifically to Hispano-Roman residents of the Iberian Peninsula,[75] where Alaric had migrated the Visigoth population. Both the Code of Euric and Breviary of Alaric borrowed heavily from the Theodosian Code. Euric, for instance, forbade intermarriage between Goths and Romans, which was already expressed in the Codex Theodosianus. The Lex Romana Visigothorum remained a source of law in the area that later became southern France long after it had been superseded in the Iberian peninsula by the Lex Visigothorum (see below).

Euric's code remained in force among the Visigothic Kingdom of Hispania (the Iberian Peninsula) until the reign of Liuvigild (568-586), who made a new one, the Codex Revisus, improving upon that of his predecessor. This work is lost, and we have no direct knowledge of any fragment of it. In the third codification, however, many provisions have been taken from the second, and these are designated by the word antiqua; by means of these antiqua we are enabled in a certain measure to reconstruct the work of Leovigild.[74]

After the reign of Leovigild, the legislation of the Visigoths underwent a transformation. New laws made by the kings were declared to be applicable to all subjects in the kingdom, of whatever race; in other words, they became territorial; and this principle of territoriality was gradually extended to the ancient code. Moreover, the conversion of Reccared (586-601) from Arianism to orthodox Christianity effaced the religious differences among his subjects, and all subjects, being Christians, had to submit to the canons of the councils, made obligatory by the kings.[74]

In 643, Visigoth king Chindasuinth (642-653) proposed a new Visigothic Code, the Lex Visigothorum (also called the Liber Iudiciorum or Forum Iudicium), which replaced both the Code of Euric and the Breviary of Alaric. His son, Recceswinth (649-672), refined this code in its rough form and issued it officially in 654. This code applied equally to both Goths and Romans, presenting "a sign of a new society of Hispania developing in the seventh century, distinctly different from Gothic or Roman".[76] The Liber Iudiciorum also marked a shift in the view of the power of law in reference to the king. It stressed that the Liber Iudiciorum alone is law, absent of any relation to any kingly authority, instead of the king being the law and the law merely an expression of his decisions.[77] The lacunae in these fragments have been filled by the aid of the law of the Bavarians, where the chief Divisions are reintroduced, divided into 12 books, and subdivided into tituli and chapters (aerae). It comprises 324 constitutions taken from Leovigild's collection, a few of the laws of Reccared and Sisebur, 99 laws of Chindasuinth, and 87 of Reccasuinth. A recension of this code of Reccasuinth was made in 681 by King Erwig (680-687), and is known as the Lex Wisigothorum renovate; and, finally, some additamenta were made by Ergica (687-702).[74]

The Liber Iudiciorum makes several striking differences from Roman law, especially concerning the issue of inheritance. According to the Liber Iudiciorum, if incest is committed, the children can still inherit, whereas in Roman law the children were disinherited and could not succeed.[78] Title II of Book IV outlines the issue of inheritance under the newly united Visigothic Code: section 1, for instance, states that sons and daughters inherit equally if their parents die instate, section 4 says that all family members should inherit if no will exists to express the intentions of the deceased, and the final section expresses a global law of Recceswinth, stating that anyone left without heirs has the power to do what they want with their possessions. This statement recalls the Roman right for a person to leave his possessions to anyone in his will, except this Visigothic law emphasizes males and females equally, whereas, in Roman law, only males (particularly the pater familias) are allowed to make a will.

Lex Burgundionum

This is the law code of the Burgundians, probably issued by king Gundobad. It is influenced by Roman law and deals with domestic laws concerning marriage and inheritance as well as regulating weregild and other penalties. Interaction between Burgundians is treated separately from interaction between Burgundians and Gallo-Romans. The law of the Burgundians shows strong traces of Roman influence. It recognizes the will and attaches great importance to written deeds, but on the other hand sanctions the judicial duel and the cojuratores (sworn witnesses).[74]

The oldest of the 14 surviving manuscripts of the text dates to the ninth century, but the code's institution is ascribed to king Gundobad (died 516), with a possible revision by his successor Sigismund (died 523). The Lex Romana Burgundionum is a separate code, containing various laws taken from Roman sources, probably intended to apply to the Burgundians' Gallo-Roman subjects. The oldest copy of this text dates to the seventh century.

Lex Salica

The exact origins of the Franks are uncertain: they were a group of Germanic peoples that settled in the lower regions of the Rhine river. They were not a unified people at the start of the third century but consisted of many tribes which were loosely connected with one another. Although they were intertwined with the Roman Empire the Franks were not a part of it. "No large body of Franks was admitted into the Empire, but individuals and small groups did cross."[79] The Romans were seen as a lower rank in Frankish society. With larger numbers the Franks over took the region of the Rhine. Latin became the secondary language to the Germanic one of the Franks and Frankish law took precedence among the people. The Romans even embraced the "Barbarians" to the north at times, making them allies to fight off the Huns.

The Franks were broken down into east and west regions. The Eastern Franks were known as the Ripuarians and those west of the Rhine were known as the Salian Franks. It was King Clovis who united the Franks under one law after defeating his rivals in 509 AD. It is during this time of unification that King Clovis developed the Salic Law.

The Lex Salica was a similar body of law to the Lex Burgundionum. It was compiled between 507 and 511 AD. The body of law deals with many different aspects of Frank society. The charges range from inheritance to murder and theft. The Salic law was used to bring order to Frank society, the main punishment for crimes being a fine with a worth designated to the type of crime. The law uses capital punishment only in cases of witchcraft and poisoning. This absence of violence is a unique feature of the Salic Law.

The code was originally brought about by the Frankish King Clovis.[79] The code itself is a blue print for Frankish society and how the social demographics were assembled. One of the main purposes of the Salic Law is to protect a family's inheritance in the agnatic succession. This emphasis on inheritance made the Salic Law a synonym for agnatic succession, and in particular for the "fundamental law" that no woman could be king of France.

The use of fines as the main reparation made it so that those with the money to pay the fine had the ability to get away with the most heinous of crimes. "Those who commit rape shall be compelled to pay 2500 denars, which makes 63 shillings."[79] Rape was not the only detailed violent crime. The murder of children is broken down by age and gender, and so is the murder of women.

Paying fines broke the society into economic and social demographics in that the wealthy were free to do as much as they could afford, whereas the fines themselves placed different values on the gender and ethnic demographics. This social capital is evident in the differences in the Salic Law's punishment for murder based on a woman's ability to bear children. Women who could bear children were protected by a 600 shilling fine while the fine for murdering a woman who could no longer bear children was only 200 shillings. All crimes committed against Romans had lesser fines than other social classes. In the case of inheritance, it is made very clear that all property belongs to the males in the family. This also means that all debt also belongs to the males of the family.

The Salic Law outlines a unique way of securing the payment of money owed. It is called the Chrenecruda (or crenecruda, chren ceude, crinnecruda).[79] In cases where the debtor could not pay back a loan in full they were forced to clear out everything from their home. If the debt still could not be paid off the owner could collect dust from all four corners of the house and cross the threshold. The debtor then turned and face the house with their next of kin gathered behind them. The debtor threw the dust over their shoulder. The person (or persons) that the dust fell upon was then responsible for the payment of the debt. The process continued through the family until the debt was paid. Chrenecruda helped secure loans within the Frankish society. It intertwined the loosely gathered tribes and helped to establish government authority. The process made a single person part of a whole group.

The Salic Law exists in two forms: the Pactus Legis Salicae, which is near to the original form approved by Clovis, and the Lex Salica, which is the edited form approved by Charlemagne. Both are published in the Monumenta Germaniae Historica's Leges series.

Lex Ripuaria

In the first half of the seventh century the Ripuarian Franks received the Ripuarian law, a law code applying only to them, from the dominating Salian Franks. The Salians, following the custom of the Romans before them, were mainly re-authorizing laws already in use by the Ripuarians, so that the latter could retain their local constitution.

The law of the Ripuarians contains 89 chapters and falls into three heterogeneous divisions. Chapters 1-31 consist of a scale of compositions; but, although the fines are calculated, not on the unit of 15 solidi, as in the Salic Law, but on that of 18 solidi, it is clear that this part is already influenced by the Salic Law. Chapters 32-64 are taken directly from the Salic Law; the provisions follow the same arrangement; the unit of the compositions is 15 solidi; but capitularies are interpolated relating to the affranchisement and sale of immovable property. Chapters 65-89 consist of provisions of various kinds, some taken from lost capitularies and from the Salic Law, and others of unknown origin.

The compilation apparently goes back to the reign of Dagobert I (629-639)

Pactus Alamannorum and Lex Alamannorum

Of the laws of the Alamanni, who dwelt between the Rhine and the Lech, and spread over Alsace and what is now Switzerland to the south of Lake Constance, we possess two different texts.[74]

The earlier text, of which five short fragments have come down to us, is known as the Pactus Alamannorum, and judging from the persistent recurrence of the expression et sic convenit, was most probably drawn up by an official commission. The reference to aifranchisement in ecciesia shows that it was composed after the conversion of the Alamanni to Christianity. There is no doubt that the text dates back at least to the reign of the Frankish king Dagobert I, i.e. to the first half of the seventh century.[74]

The later text, known as the Lex Alamannorum, dates from a period when Alamannia was independent under national dukes, but recognized the theoretical suzerainty of the Frankish kings. There seems no reason to doubt the St. Gall manuscript, which states that the law had its origin in an agreement between the great Alamannic lords and Duke Lantfrid, who ruled the duchy from 709 to 730.[74]

Leges Langobardorum

We possess a fair amount of information on the origin of the code of laws of the Lombards. The first part, consisting of 388 chapters, also known as the Edictus Langobardorum, and was promulgated by King Rothari at a diet held at Pavia on 22 November 643. This work, composed at one time and arranged on a systematic plan, is very remarkable. The compilers knew Roman law, but drew upon it only for their method of presentation and for their terminology; and the document presents Germanic law in its purity. Rothar's edict was augmented by his successors: Grimwald (668) added nine chapters; Liutprand (713-735), fifteen volumes, containing a great number of ecclesiastical enactments; Ratchis (746), eight chapters; and Aistulf (755), thirteen chapters. After the union of the Lombards to the Frankish kingdom, the capitularies made for the entire kingdom were applicable to Italy. There were also special capitularies for Italy, called Capitula Italica, some of which were appended to the edict of Rothar.[80]

At an early date, compilations were formed in Italy for the use of legal practitioners and jurists. Eberhard, duke and margrave of Rhaetia and Friuli, arranged the contents of the edict with its successive additamenta into a Concordia de singulis causis (829-832). In the tenth century a collection was made of the capitularies in use in Italy, and this was known as the Capitulare Langobardorum. Then appeared, under the influence of the school of law at Pavia, the Liber legis Langobardorum, also called Liber Papiensis (beginning of 11th century), and the Lombarda (end of 11th century), in two forms, that given in a Monte Cassino manuscript and known as the Lombarda Casinensis and the Lombarda Vulgata.[80] In some, but not all, manuscripts of the Liber Papiensis each section of the edict is accompanied by specimen pleadings setting out the cause of action: in this way it comes near to being a treatment of substantive law as opposed to a simple tariff of penalties as found in the other Leges barbarorum.

There are editions of the Edictus, the Concordia, and the Liber Papiensis by F. Bluhme and A. Boretius in the Monumenta Germaniae Historica series, Leges (in folio) vol. iv. Bluhme also gives the rubrics of the Lombardae, which were published by F. Lindenberg in his Codex legum antiquarum in 1613. For further information on the laws of the Lombards see J. Merkel, Geschichte des Langobardenrechts (1850); A. Boretius, Die Kapitularien im Langobardenreich (1864); and C. Kier, Edictus Rotari (Copenhagen, 1898). Cf. R. Dareste in the Nouvelle Revue historique de droit français et étranger (1900, p. 143).[80]

Lombard law, as developed by the Italian jurists, was by far the most sophisticated of the early Germanic systems, and some (e.g. Frederic William Maitland) have seen striking similarities between it and early English law.[81] It remained living law, subject to modifications, both in the Kingdom of the Lombards that became the Carolingian Kingdom of Italy and in the Duchy of Benevento that became the Kingdom of Naples and continued to play a role in the latter as late as the 18th century. The Libri Feudorum, explaining the distinctive Lombard version of feudalism, were frequently printed together with the Corpus Juris Civilis and were considered the academic standard for feudal law, influencing other countries including Scotland.

Lex Baiuvariorum

We possess an important law of the Bavarians, whose duchy was situated in the region east of the river Lech. Parts of this law have been taken directly from the Visigothic law of Euric and from the law of the Alamanni. The Bavarian law, therefore, is later than that of the Alamanni. It dates unquestionably from a period when the Frankish authority was very strong in Bavaria, when the dukes were subjects of the Frankish kings. The law's compilation is most commonly dated between 744 and 748, by the following argument; Immediately after the revolt of Bavaria in 743 the Bavarian Duke Odilo (died 748) was forced to submit to Pippin the Younger and Carloman, the sons of Charles Martel, and to recognize Frankish suzerainty. A little earlier, in 739, the church of Bavaria had been organized by St. Boniface, and the country divided into several bishoprics; and we find frequent references to these bishops (in the plural) in the law of the Bavarians. On the other hand, we know that the law is anterior to the reign of Duke Tassilo III (749-788). The date of compilation must, therefore, be placed between 744 and 748.[82] Against this argument, however, it is very likely that Odilo recognized Frankish authority before 743; he took refuge at Charles Martel's court that year and married one of Martel's daughters. His "revolt" may have been in support of the claims of Pippin and Carloman's half-brother Grifo, not opposition to Frankish rule per se. Also, it is not clear that the Lex Baiuvariorum refers to multiple bishops in the duchy at the same time; when a bishop is accused of a crime, for instance, he is to be tried by the duke, and not by a council of fellow bishops as canon law required. So, it is possible that the Bavarian law was compiled earlier, perhaps between 735 (the year of Odilo's succession) and 739.

Lex Frisionum

The Lex Frisionum of the duchy of Frisia consists of a medley of documents of the most heterogeneous character. Some of its enactments are purely pagan, thus one paragraph allows the mother to kill her new-born child, and another prescribes the immolation to the gods of the defiler of their temple; others are purely Christian, such as those that prohibit incestuous marriages and working on Sunday. The law abounds in contradictions and repetitions, and the compositions are calculated in different moneys. From this it appears the documents were merely materials collected from various sources and possibly with a view to the compilation of a homogeneous law. These materials were apparently brought together at the beginning of the ninth century, at a time of intense legislative activity at the court of Charlemagne.[80]

Lex Saxonum

The Lex Saxonum has come down to us in two manuscripts and two old editions (those of B. J. Herold and du Tillet), and the text has been edited by Karl von Richthofen in the Mon. Germ. hist, Leges, v. The law contains ancient customary enactments of Saxony, and, in the form in which it reached us, is later than the conquest of Saxony by Charlemagne. It is preceded by two capitularies of Charlemagne for Saxony, the Capitulatio de partibus Saxoniae (A. Boretius i. 68), which dates undoubtedly from 782, and is characterized by great severity, death being the penalty for every offence against the Christian religion; and the Capitulare Saxonicum (A. Boretius i. 71), of the 28 October 797, in which Charlemagne shows less brutality and pronounces simple compositions for misdeeds that formerly warranted death. The Lex Saxonum apparently dates from 803, since it contains provisions that are in the Capitulare legi Ribuariae additum of that year. The law established the ancient customs, at the same time eliminating anything that was contrary to the spirit of Christianity; it proclaimed the peace of the churches, whose possessions it guaranteed and whose right of asylum it recognized.[80]

See also

- Ewa ad Amorem, traditionally counted among the leges barbarorum

- Medieval Scandinavian laws

Notes

- Probably related to þeihs "time" (from PGmc *þinhaz) and meaning originally the time at which the assembly was appointed to meet.[27]

- From PGmc *maþla- "speech, assembly".[30]

- The etymology is unclear but probably represents a Proto-Germanic *aiwa-, which may have been a combination of two roots, one related to Sanskrit eva (law) and one related to Latin aevum eternity.[35]

- The term is the most frequent one found in Old English and Old High German. In the Nordic languages the term mangæld is used. Alternative terms in the Leges include leudardi, from leod ("man").[54]

- A second early listing of some laws, the fragmentary Edictum Theodorici, is either ascribed to the Ostrogoths in Italy (probably in the reign of Theodoric the Great) or is another example of a Visigothic code by their king Theodoric II.[61][62]

References

- Dilcher 2011, p. 251.

- Fruscione 2010.

- Timpe & Scardigli 2010, p. 801.

- Shoemaker 2018, pp. 251–252.

- Shoemaker 2018, p. 249.

- Shoemaker 2018, p. 251.

- Dilcher 2011, pp. 241–242.

- Schmidt-Wiegand 2010a, p. 389.

- Lück 2010, p. 423.

- Timpe & Scardigli 2010, pp. 790–791.

- Timpe & Scardigli 2010, p. 811.

- Dilcher 2011, p. 245.

- Timpe & Scardigli 2010, pp. 798–799.

- Dilcher 2011, p. 243.

- Timpe & Scardigli 2010, pp. 811–812.

- Lück 2010, pp. 423–424.

- Timpe & Scardigli 2010, pp. 800–801.

- Dilcher 2011, pp. 246–247.

- Schmidt-Wiegand 2010a, p. 396.

- Beck & Wenskus 2010, p. 887.

- Hardt 2010, p. 1177.

- Beck & Wenskus 2010, pp. 900–901.

- Hardt 2010, p. 1178.

- Hardt 2010, p. 1179.

- Drew 1991, p. 23.

- Beck & Wenskus 2010, p. 896.

- Beck & Wenskus 2010, pp. 886.

- Beck & Wenskus 2010, pp. 886–887.

- Green 1998, pp. 34–35.

- Schmidt-Wiegand 2010b, p. 381.

- Schmidt-Wiegand 2010c, p. 382.

- Lück 2010, p. 434.

- Naumann & Schmidt-Wiegand 2010, pp. 535–537.

- Naumann & Schmidt-Wiegand 2010, p. 537.

- Schmidt-Wiegand 2010d, pp. 70–71.

- Green 1998, pp. 31–32.

- Schmidt-Wiegand 2010d, p. 70.

- Green 1998, pp. 31–34.

- Schmidt-Wiegand 2010d, p. 72.

- Karras 2006, pp. 124.

- Schulze 2010, p. 480.

- Karras 2006, p. 128.

- Schulze 2010, p. 483.

- Schulze 2010, p. 488.

- Buchholz 2008, p. 1193.

- Schulze 2010, p. 481.

- Karras 2006, pp. 124, 127–130, 139–140.

- Schumann 2008a, pp. 1807–1809.

- Schumann 2008b, pp. 1695–1696.

- Körntgen 2010, p. 359.

- Schmidt-Wiegand 2010e, p. 917.

- Beck 2010, p. 215.

- Körntgen 2010, pp. 459–460.

- Schmidt-Wiegand 2010e, pp. 914–915.

- Schmidt-Wiegand 2010e, pp. 922–923.

- Schmidt-Wiegand 2010e, p. 915-917.

- Schmidt-Wiegand 2010e, pp. 917–918.

- Schmidt-Wiegand 2010b, p. 585.

- Schmidt-Wiegand 2010b, pp. 585–586.

- Schmidt-Wiegand 2010a, p. 392.

- Drew 1991, p. 22.

- Wormald 2003, pp. 27.

- Lück 2010, pp. 425–426.

- Lück 2010, p. 426.

- Drew 1991, p. 21-22.

- King, Law and Society in the Visigothic Kingdom (Cambridge University Press) 1972:36-37

- King, Law and Society in the Visigothic Kingdom (Cambridge University Press) 1972:38-39

- King, Law and Society in the Visigothic Kingdom (Cambridge University Press) 1972:39

- King, Law and Society in the Visigothic Kingdom (Cambridge University Press) 1972:44-45.

- King, Law and Society in the Visigothic Kingdom (Cambridge University Press) 1972:45-46

- King, Law and Society in the Visigothic Kingdom (Cambridge University Press) 1972:45

- King, Law and Society in the Visigothic Kingdom (Cambridge University Press) 1972:7

- Carr, Vandals to Visigoths (University of Michigan Press) 2002:36

- Chisholm 1911, p. 775.

- Carr, Vandals to Visigoths (University of Michigan Press) 2002:29

- Heather, The Visigoths from the Migration Period to the Seventh Century (Boydell Press) 1999:261

- Heather, The Visigoths from the Migration Period to the Seventh Century (Boydell Press) 1999:268

- Heather, The Visigoths from the Migration Period to the Seventh Century (Boydell Press) 1999:189

- Katherine Fischer Drew, The laws of the Salian Franks (Pactus legis Salicae), Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press (1991).

- Chisholm 1911, p. 776.

- Pollock and Maitland, History of English Law before the Time of Edward I vol. 1 p. 77.

- Chisholm 1911, pp. 775–776.

Sources

- Beck, Heinrich (2010) [2005]. "Sühne". Germanische Altertumskunde Online.

- Beck, Heinrich; Wenskus, Reinhard; et al. (2010) [1984]. "Ding". Germanische Altertumskunde Online.

- Buchholz, Stephan (2008). "Ehe". Handwörterbuch zur deutschen Rechtsgeschichte. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). pp. 1192–1213.

- Dilcher, Gerhard (2011). "Germanisches Recht". Handwörterbuch zur deutschen Rechtsgeschichte. Vol. 2 (2nd ed.). pp. 241–252.

- Drew, Katharine Fischer (1991). The Laws of the Salian Franks. University of Pennsylvania Press. doi:10.9783/9780812200508. ISBN 978-0-8122-8256-6.

- Fruscione, Daniela (2010). "On "Germanic"". The Heroic Age: A Journal of Medieval Northwestern Europe. 14.

- Green, Dennis H. (1998). Language and History in the Early Germanic World (2001 ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-79423-7.

- Hardt, Matthias (2010) [2006]. "Volksversammlung". Germanische Altertumskunde Online.

- Karras, Ruth Mazo (2006). "The History of Marriage and the Myth of Friedelehe". Early Medieval Europe. 14 (2): 119–152. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0254.2006.00177.x. S2CID 162024433.

- Körntgen, Ludger (2010) [2000]. "Kompositionensysteme". Germanische Altertumskunde Online.

- Lück, Heiner (2010) [2003]. "Recht". Germanische Altertumskunde Online. pp. 418–447.

- Naumann, Hans-Peter; Schmidt-Wiegand, Ruth (2010) [2003]. "Rechtssprache". Germanische Altertumskunde Online.

- Schmidt-Wiegand, Ruth (2010a) [2001]. "Leges". Germanische Altertumskunde Online. pp. 419–447.

- Schmidt-Wiegand, Ruth (2010b) [2003]. "Volksrechte". Germanische Altertumskunde Online.

- Schmidt-Wiegand, Ruth (2010c) [2001]. "Mallus". Germanische Altertumskunde Online.

- Schmidt-Wiegand, Ruth (2010d) [1994]. "Ēwa". Germanische Altertumskunde Online.

- Schmidt-Wiegand, Ruth (2010e) [2006]. "Wergeld". Germanische Altertumskunde Online.

- Schulze, Reiner (2010) [1986]. "Eherecht". Germanische Altertumskunde Online. pp. 961–999.

- Schumann, Eva (2008a). "Friedelehe". Handwörterbuch zur deutschen Rechtsgeschichte. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). pp. 1805–1807.

- Schumann, Eva (2008b). "Kebsehe, Kebskind". Handwörterbuch zur deutschen Rechtsgeschichte. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). pp. 1695–1697.

- Shoemaker, Karl (2018). "Germanic Law". In Heikki Pihlajamäki; Markus D. Dubber; Mark Godfrey (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of European Legal History. Oxford University Press. pp. 249–263. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198785521.013.11. ISBN 978-0-19-878552-1.

- Timpe, Dieter; Scardigli, Barbara; et al. (2010) [1998]. "Germanen, Germania, Germanische Altertumskunde". Germanische Altertumskunde Online. pp. 363–876.

- Wormald, C. Patrick (2003). "The 'leges barbarorum': Law and ethnicity in the post-Roman West". In Goetz, Hans-Werner; Jarnut, Jan; Pohl, Walter (eds.). Regna and gentes. The relationship between late antique and early medieval peoples and kingdoms in the transformation of the Roman world. Leiden. pp. 21–53.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Further reading

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Germanic Laws, Early". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 11 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 775–776.

External links

- Leges Romanae barbarorum

- Volterra Project at UCL

- Information on the leges Barbarorum and the respective manuscript tradition on the Bibliotheca legum regni Francorum manuscripta website, A database on Carolingian secular law texts (Karl Ubl, Cologne University, Germany, 2012).