Getty kouros

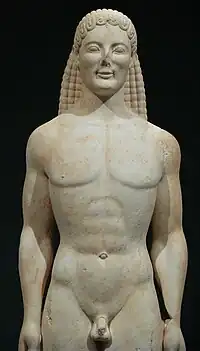

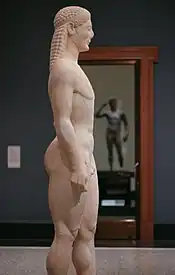

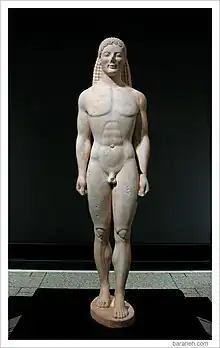

The Getty kouros is an over-life-sized statue in the form of a late archaic Greek kouros.[1] The dolomitic marble sculpture was bought by the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, California, in 1985 for ten million dollars and first exhibited there in October 1986.[2][3][4]

Despite initial favourable scientific analysis of the patina and aging of the marble, the question of its authenticity has persisted from the beginning. Subsequent demonstration of an artificial means of creating the de-dolomitization observed on the stone has prompted a number of art historians to revise their opinions of the work. If genuine, it is one of only twelve extant complete kouroi. If fake, it exhibits a high degree of technical and artistic sophistication by an as-yet unidentified forger. Its status has remained undetermined: latterly the museum's label read "Greek, about 530 B.C., or modern forgery".[5] Although the statue was removed from public display after the 2018 renovations, Dr. Timothy Potts, the current director of the Getty, reinforces that the kouros has still not been confirmed of its authenticity. Dr. Potts states that the sculpture was taken off of display due to the dubious nature around the work.[6]

Provenance

The kouros first appeared on the art market in 1983 when the Basel dealer Gianfranco Becchina offered the work to the Getty's curator of antiquities, Jiří Frel. Frel deposited the sculpture (then in seven pieces) at Pacific Palisades along with a number of documents purporting to attest to the statue's authenticity. These documents traced the provenance of the piece to a collection in Geneva of Dr. Jean Lauffenberger who, it was claimed, had bought it in 1930 from a Greek dealer. No find site or archaeological data was recorded. Amongst the papers was a suspect 1952 letter allegedly from Ernst Langlotz, then the preeminent scholar of Greek sculpture, remarking on the similarity of the kouros to the Anavyssos youth in Athens (NAMA 3851). Later inquiries by the Getty revealed that the postcode on the Langlotz letter did not exist until 1972, and that a bank account mentioned in a 1955 letter to an A.E. Bigenwald regarding repairs on the statue was not opened until 1963.[7] The documentary history of the sculpture was evidently an elaborate fake and therefore there are no reliable facts about its recent history before 1983. At the time of acquisition, the Getty Villa's board of trustees split over the authenticity of the work. Federico Zeri, founding member of board of trustees and appointed by Getty himself, left the board in 1984 after his argument that the Getty kouros was a forgery and should not be bought was rejected.[8][9]

Stylistic analysis

The Getty kouros is highly eclectic in style. The development of kouroi as delineated by Gisela Richter[10] suggests the date of the Getty youth diminishes from head to feet: At its top, the hair is braided into a wig-like mass of 14 strands, each of which ends in a triangular point. The closest parallel here is to the Sounion kouros (NAMA 2720) of the late 7th century/early 6th century, which also displays 14 braids, as does the New York kouros (NY Met. 32.11.1). However, the Getty kouros's hair exhibits a rigidity, very unlike the Sounion Group. Descending to the hands, the last joints of the fingers turn in at right angles to the thighs, recalling the Tenea kouros (Munich 168) of the 2nd quarter of the 6th century. Further down, a late archaic naturalism becomes more pronounced in the rendering of the feet similar to kouros No. 12 from the Ptoon sanctuary (Thebes 3), as is the broad oval plinth which in turn is comparable to a base found on the Acropolis. Both Ptoon 12 and the Acropolis base are assigned to the Group of Anavyssos-Ptoon 12 and dated to the third quarter of the 6th century. Anachronizing elements are not unknown in authentic kouroi, but the disparity of up to a century is a strikingly unusual feature of the Getty sculpture.

Technical analysis

Despite being of Thasian marble, the kouros cannot be securely ascribed to an individual workshop of northern Greece nor indeed to any ancient regional school of sculpture. Archaic kouroi conform to a canon of measurement and proportion (albeit with strong local accents) to which the Getty example also adheres; a comparison of like elements in other kouroi is both a test of authenticity and additional clue to the origin of the sculpture. There is little in the tool marks, carving methods and detailing to contradict an ancient origin of the piece. Although there is a small sample with which to compare (some 200 fragments and only twelve complete statues of the same type) there are atypical aspects of the Getty work that may be observed. The oval plinth is an unusual shape and larger than in other examples, suggesting the figure was free-standing rather than fixed with lead in a separate base. Also, the ears are not symmetrical: they are at different heights with the left oblong and the right rounder, implying the sculptor was using two distinct schema or none at all.[11] Furthermore, there are a number of flaws in the marble, most prominently on the forehead, which the sculptor has worked around by parting the hair curls at the centre; ancient examples survive of projects being abandoned by sculptors when such flaws in the stone were revealed.[12]

Perhaps the most striking evidence suggestive of the kouros's antiquity is a subtlety regarding the direction of motion of the figure. Even though the youth presents square to the viewer, all kouroi have understated indicators of a turn either to the left or the right depending on where they were originally placed in the temple sanctuary; i.e., they would seem to turn towards the naos. In the case of the Getty youth the left foot is parallel with the step axis of the right foot rather than turning outwards as would occur if the figure were moving directly forwards. Therefore, the statue is making motion toward his right, which Ilse Kleemann asserts is "one of the strongest pieces of evidence of its authenticity".[13] Other features that suggest a similarity with known originals include the helicoid curls of the hair, closest in form to the west Cyclidian Kea kouros (NAMA 3686), the Corinthian form of the hands and the sloping shoulders akin to the Tenea kouros and the broad plinth and feet comparable to the Attic or Cyclidian Ptoon 12. That the Getty kouros cannot be identified with any one local atelier does not disqualify it as a genuine, but if real it admits a lectio difficilior into the corpus of archaic sculpture.

Some indication of tool marks remain on the work. Though the surface is weathered (or artificially abraded) and it is not clear if emery was used, there are heavy claw marks on the plinth and the use of a point in some of the finer detailing. For example, there are point marks in the outline of the curls, between the fingers and in the cleft of the buttocks, also traces of the point in the arches of the feet and at random over the plinth. Though the tools evident here (fine point, slope chisel, claw chisel) are not inappropriate for a late 6th century sculpture their application might be problematic. Stelios Triantis remarks, "no sculptor of kouroi would hollow out with a fine point, nor incise outlines with this tool".[14]

In 1990, Dr. Jeffrey Spier published the discovery of a kouros torso,[15] a certain forgery that exhibited notable technical similarities to the Getty kouros. After samples were taken that determined the fake torso was of the same dolomitic marble as the Getty piece the torso was purchased by the museum for study purposes. The fake's sloping shoulders and upper arms, volume of chest, rendering of the hands and genitals all suggest the same hand as the Getty's example, although the aging had been crudely done with an acid bath and the application of iron oxide. Further investigation has shown the torso and the kouros are not from the same block and the sculpting techniques are dramatically different (down to the use of power tools on the torso).[16] Their relationship if any is still to be determined.

Archaeometry

The Getty commissioned two scientific studies on which it based its decision to buy the statue. The first was by Norman Herz, a professor of geology at the University of Georgia, who measured the carbon and oxygen isotope ratios, and traced the stone to the island of Thasos. The marble was found to have a composition of 88% dolomite and 12% calcite, by X-ray diffraction. His isotopic analysis revealed that δ18O = -2.37 and δ13C = +2.88, which from database comparison admitted one of five possible sources: Denizli, Doliana, Marmara, Mylasa, or Thasos-Acropolis. Further, trace element analysis of the kouros eliminated Denizli. With the high dolomite content Thasos was determined to be the likeliest source with a 90% probability.[17] The second test was by Stanley Margolis, a geology professor at the University of California at Davis. He showed that the dolomite surface of the sculpture had undergone a process called de-dolomitization, in which the magnesium content had been leached out, leaving a crust of calcite, along with other minerals. Margolis determined that this process could occur only over the course of many centuries and under natural conditions, and therefore could not be duplicated by a forger.

In the early 1990s, the marine chemist Miriam Kastner produced an experimental result which cast doubt on Margolis's thesis by artificially inducing de-dolomitization in the laboratory, a result since confirmed by Margolis. Although this does admit the possibility that the kouros was synthetically aged by a forger, the procedure is a complicated and time-consuming one. The unlikeliness of a forger using such experimental methods in what is still an uncertain science has prompted the Getty's antiquities conservator to remark "when you consider a forger actually repeating the procedure you begin to leave the realm of practicality".[18]

References

- Getty Villa, Malibu, inv. no. 85.AA.40.

- Thomas Hoving. False Impression, The Hunt for Big-Time Art Fakes, 1997, p. 298.

- Sorensen, Lee. Frel, Jiří K. In The Dictionary of Art Historians. Accessed 28/8/2008.

- MICHAEL KIMMELMAN. In "ART; Absolutely Real? Absolutely Fake?". Accessed 26/1/2014

- J. Paul Getty Museum. Statue of a kouros. Retrieved September 2, 2008.

- L.A. Times Review: Something’s missing from the newly reinstalled antiquities collection at the Getty Villa retrieved 03/05/2020.

- Marion True. The Getty Kouros: Background on the Problem, in The Getty Kouros Colloquium, 1993, p. 13.

- Hanley, Anne (1998-10-07). "Obituary: Federico Zeri". The Independent. Retrieved 2014-01-09.

- "Zeri, Federico". Dictionary of Art Historians. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- G.M.A. Richter. Kouroi: Archaic Greek Youths. A Study of the Development of the Kouros Type in Greek Sculpture. 1970.

- I. Trianti. Four Kouroi in One?, in The Getty Kouros Colloquium, 1993.

- In the quarries of Naxos at Apollonas, Melanes and Flerio.

- Ilse Kleemann, On the Authenticity of the Getty Kouros, in The Getty Kouros Colloquium, 1993, p. 46

- Stelios Triantis. Technical and Artistic Deficiencies of the Getty Kouros in The Getty Kouros Colloquium, p. 52.

- J. Spier. "Blinded by Science", The Burlington Magazine, September 1990, pp. 623–631.

- Marion True, op. cit, pp. 13–14.

- Norman Herz and Marc Waelkens. Classical Marble, 1988, p. 311.

- Michael Kimmelman Absolutely Real? Absolutely Fake?, NYT, August 4th, 1991. Accessed 29/8/2008

Sources

- Bianchi, Robert Steven (1994). "Saga of the Getty Kouros". Archaeology. 47 (3): 22–23. JSTOR 41766561.

- Podney, J. (1992). A Sixth Century B.C. Kouros in the J. Paul Getty Museum. J. Paul Getty Museum.

- Kokkou, A, ed. (1993). The Getty Kouros Colloquium: Athens, 25-27 May 1992. J. Paul Getty Museum.

- Herz, N.; Waelkens, M. (1988). Herz, Norman; Waelkens, Marc (eds.). Classical Marble: Geochemistry, Technology, Trade. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-015-7795-3. ISBN 978-90-481-8313-5.

- Spier, Jeffrey (1990). "Blinded by Science: The Abuse of Science in the Detection of False Antiquities". The Burlington Magazine. 132: 623–631. JSTOR 884431.

- True, Marion (1987). "A Kouros at the Getty Museum". The Burlington Magazine. 129 (1006): 3–11. JSTOR 882884.