Gilles (stock character)

Gilles (French pronunciation: [ʒil])—sometimes Gille—is a stock character of French farce and Commedia dell'Arte. He enjoyed his greatest vogue in 18th-century France, in entertainments both at the fairgrounds of the capital and in private and public theaters, though his origins can be traced back to the 17th century and, possibly, the century previous. A zanni, or comic servant, he is a type of bungling clown, stupid, credulous, and lewd—a character that shares little, problematically, with the sensitive figure in Watteau's famous portrait that, until the latter half of the 20th century, bore his name alone.[1] Gilles fades from view in the 19th century, to persist in the 20th and 21st as the Belgian Gilles of Binche Carnival.

16th–17th centuries

Gilles' origins are obscure. There was a zanni Giglio in the Italian troupe of the academic Intronati as early as 1531, and some historians link him to Gilles.[2] But no line of succession has been traced. The French expression "faire gilles", meaning "to go bankrupt" or "to run away", dates from the 16th century, and some dictionaries find a source for both the name and the character in the phrase, since "the Gilles of the fair", by their authority, "is he who runs away when he is called."[3]

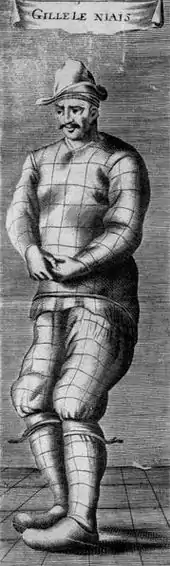

The most likely origin of the name and type is the 17th-century Gilles le Niais (Gilles the Simpleton), a character who may or may not have known multiple incarnations. According to some lines in Les Véritables prétieuses (1660) by Antoine Baudeau de Somaize, Gilles le Niais was the creation of a single actor, the Sieur de la Force, said to have descended from a venerable line of French farceurs, most immediately from Guillot-Gorju.[4] His small troupe performed, around 1646, farces that he himself composed, laced with songs that were popular among the idlers and flâneurs of the Pont-Neuf.[5] His name appears among several of the Mazarinades following the uprising of the Fronde: Le Dialogue burlesque de Gilles le Niais et du capitan Spacamon (The Burlesque Dialogue between Gilles le Niais and Captain Spacamon, 1649), Les Entretiens sérieux de Jodelet et de Gilles le Niais, rétourné de Flandres, sur le temps présent (The Serious Discussions of Jodelet with Gilles le Niais, back from Flanders, on the Present Times, 1649), and Le Véritable Gilles le Niais, en vers burlesques (The Real Gilles le Niais, in Burlesque Verse, n.d.).[6]

But this claim of single parentage is weakened by Victor Fournel's admission that Gilles le Niais could have been "a sobriquet of a type, applied to several personages".[7] What seems most clearly beyond dispute is that the copiously documented appearances of Gilles the comic servant at the Parisian fairs of the 18th century, the Foires Saint-Germain and Saint-Laurent, owed their origins to an actor-tumbler called Marc, who in 1697 first performed as Gilles at the popular Foire Saint-Germain.[8]

18th century

At the fairgrounds

Marc's Gilles was followed in quick succession at the fairs by Gilles of other actors and acrobats: the tumblers Benville and Drouin, in the same year as Marc's debut;[9] Crespin, called Gilles le Boiteux (Gilles the Gimp), "a performer of 'grace and lightness' despite the infirmity of his body", in 1701;[10] Nicolas Maillot, "one of the best Gilles to appear at the Foire", in 1702;[11] and Génois, a grimacing rope-dancer in wooden clogs, in 1711.[12]

Gilles was sometimes given a major role in a "regular" comedy, such as La Conquête de la Toison d'or (The Conquest of the Golden Fleece, 1724) by Lesage and Dorneval.[13] But he could be found more commonly at the fairgrounds (as the citations above suggest) at the acrobatic venues and, rather more revealingly, in the entertainments known as parades. An outdoor performance, usually on a trestle-stage, that was contrived to lure spectators inside a theater, the parade was typically comprised, as William Driver Howarth notes, of five standard elements:

- A "send-up of the conventional Italian plot" in which two lovers are united, despite parental opposition, by the machinations of the so-called "first" zanni, the cleverer of two comic servants. (In the parade, "the heroine is anything but a virtuous ingénue", unlike her counterpart in conventional comedy.)

- "Disguises, verbal altercations and beatings", in which the "second" zanni, the fool, usually feels the brunt of the mayhem.

- Dialogue "full of sexual innuendo and scatological reference."

- A spoofing of "popular Parisian speech, typified by the ubiquitous use of cuirs (irregular liaisons, and ... intrusive consonants ...),[14] together with malapropisms, pleonasms and other standard sources of verbal comedy."

- "[L]iterary parody, mock-heroic and burlesque devices."[15]

The focus here is upon that fool who feels the brunt of the mayhem: he was almost invariably Gilles. In 1756 a three-volume collection of parades was published anonymously as Théâtre des Boulevards,[16][17] and in its pages Gilles acquires a distinct sharpness of outline. Robert Storey traces it with trenchancy: "A character of more simplicity than sense and of less decency than either, Gilles inherits the ignoble side of the commedia's comic masks."[18] His inventiveness rarely exceeds the stratagem of Isabelle, Grosse par vertu (Isabelle, Knocked-up by Virtue), in which he advises his mistress to enlarge her belly with a hidden tureen, thereby convincing the amorous Doctor that he has been beaten to the erotic prize.[17] When Arlequin, the first zanni (and his superior in every way), tells him that shit is fetching high prices on the market, he produces a large batch of it and peddles it through the streets ("Who'd like some of my shit? ... it's nice and fresh"—Le Marchand de Merde: The Shit Merchant, scene X).[19] Gilles's appetites are, in one of his chroniclers' words, "prodigiously insatiable",[20] and his guardian spirits ("Sainte Merde!")[21] are always provocatively profane. If his Italian predecessor, Pedrolino, "often shares the ether with Ariel," as Storey writes, he himself "tumbles, with Puck's witless companions, among the cornflowers."[22]

In the salons and private theaters

Quite early in the century, the parade acquired the status of what Howarth calls a "cult entertainment" among the leisured classes.[23] Thomas-Simon Gueullette, a lawyer and "friend of letters, of theater, and of pleasure" (in the words of his biographer, J.-E. Gueullette),[24] was so enamored of a parade he had seen one night around 1707 at the Foire Saint-Laurent that he and his friends performed it at a private soirée.[25] It proved such a success that Gueullette formed a theater society, built a playhouse at Auteuil, and began receiving "an astonishing concourse of spectators of the first rank" to laugh at the ribaldry of Gilles.[26] After he established other theaters at Maisons and Choisy, the parade "very soon became à la mode."[18] Writers of ambition, such as Charles Collé and Barthélemy-Christophe Fagan, seized upon the entertainment[17] and soon "made it one of the favourite genres performed in the 'théâtres de société', or private playhouses, which were to blossom from about 1730 onwards in aristocratic châteaux and the townhouses of the capital."[15] In the 1760s, the author of Le Mariage de Figaro, Beaumarchais, set himself to writing parades, most of which were probably performed in the private theater of his friend and patron, Charles-Guillaume Le Normant d'Etiolles, ex-husband of Madame de Pompadour.[27] Even in a piece like Les Bottes de sept lieues (The Seven-League Boots), the "least substantial" of Beaumarchais' parades, Gilles gives ample evidence of that winning credulity that "makes him a ready victim for Arlequin's comic invention."[28]

In the boulevard theaters

Gilles acquired a kind of respectability toward the end of the century, when he was adopted by the boulevard theaters that catered to the predominantly middle-class. We find his name among many of the comedies at the Théâtre de la Cité (1792–1807) and the Variétés Amusantes (1778–89, 1793–98).[29]

Gilles and Pierrot

As the famous portrait by Watteau attests (see inset), Gilles and Pierrot were often confused during this century. The scholar Ludovic Celler suggests that the actor Nicolas Maillot, who, as noted above, played Gilles from 1702, was responsible for the confusion: "at first," Celler writes, Maillot

played the roles of Pierrot under the pseudonym of Gilles: since he was talented and successful, his nom de guerre served to designate the employ. Hence was created the Gilles who took, as a result, a rather important place in the parades of the Boulevards and caused the French Pierrot to be almost completely forgotten ...[30]

Apparently, the confusion was abetted by the erosion of integrity of Pierrot's original character: Giuseppe Giaratone, who played Pierrot in the Comédie-Italienne of the previous century, had brought a rich and unifying consistency to the role.[31] But as the Pierrots of the Foires began to multiply—among dancers, tumblers, and actors—and to accommodate themselves to the disparate Foire genres—puppet shows, comic operas, and every imaginable permutation of both mute and spoken theater—his character began inevitably to coarsen.[32] It is therefore not surprising that Colombine should call Pierrot a "Gille" in Alexis Piron's L'Ane d'Or (The Golden Ass, 1725) or that a police report detailing the suspicious goings-on in Lesage's prologue to Arlequin, valet de Merlin (Harlequin, Merlin's Valet, 1718) should refer to Pierrot indiscriminately as "Pierrot" or as "Gilles".[33] (It should also not be surprising that, when the illustrious Pierrot Hamoche was forbidden, in 1721, to play opéras-comiques, impelling Lesage and Dorneval to lay his Pierrot to rest in Les Funérailles de la Foire [The Foire's Funeral, 1718], Gilles came bustling in during their subsequent play, Le Rappel de la Foire à la Vie [The Recall of the Foire to Life, 1721], to take his double's place.[34] As late as the second decade of the 19th century, we find Pierrot's name changing inexplicably to "Gilles" in the middle of the script of a pantomime performed at the Théâtre des Funambules.)[35] The two characters were often so much alike as to be virtually indistinguishable.

As Francis Haskell has pointed out (and the remarks above imply), not only did Gilles "wear the same costume" as Pierrot, but both generally "had the same character" throughout the 18th century: Pierrot, like Gilles, "was a farcical creature, not a tragic or sensitive one".[36] (Pierrot will become tearful and incipiently tragic only in the middle of the 19th century, in the hands of Paul Legrand.)[37] "It is", writes Haskell, "hard to resist the conclusion that the consumptive Watteau has invested the figure of Gilles with some degree of self-identification, and Mrs. [ Erwin ] Panofsky has also pointed out that on many other occasions when painting Pierrot figures Watteau not only gave them a predominance which was absolutely not justified by the nature of the parts they were called upon to act, but may even have hinted at something Christ-like in their role."[36] As Haskell seems to be implying, there may be at least as much Watteau as either Gilles or Pierrot in the portrait.

19th–21st centuries

If it was Maillot who "caused the French Pierrot to be almost completely forgotten", it was the Pierrot of the great mime Deburau who turned the tables on Gilles in the early 19th century. Partly because of Deburau's dominance in both the theatrical and literary imaginations of French enthusiasts of the Commedia dell'Arte,[38] Gilles faded from view in that century, appearing occasionally in a vaudeville like Gilles en deuil de lui-même (Gilles in Mourning for Himself, 1847) at the Théâtre de la Rue de Chartres or a farce like Mélésville's Les Deux Gilles (The Two Gilles, 1855) at the Folies-Nouvelles.[39] At the end of the century, he makes a brief spectral appearance in Albert Giraud's Pierrot lunaire (overlooked in Arnold Schoenberg's selective immortalizing of that work).[40] In the 20th century and later in the 21st, he survives most robustly at the Binche Carnival in Belgium—though a redoubtable student of that carnival[41] insists that its many Gilles share with the zanni of the French fairgrounds only one thing: his name.

Notes

- The art historian Pierre Rosenberg notes that, since 1952, "Pierrot clearly has won over Gilles" (p. 430) as the title of Watteau's painting, adding that François Moureau "has proved that Watteau most surely painted a Pierrot" (p. 433). Moureau's "proof", offered in an appendix to the collection in which Rosenberg's essay appears, rests upon the assumption that Gilles's costume remained invariant throughout his career, beginning with Gilles le Niais (though it is only conjecture—unmentioned by Moureau—that Gilles le Niais formed part of his pedigree): see the illustration at the top of this page and Moureau's note 14 (p. 526). Moureau is apparently unaware of the role that Nicolas Maillot played in the evolution of Gilles's character and costume (see Gilles and Pierrot below).

- Doutrepont, II, 74; Mic, p. 33n; Duchartre, p. 254.

- Doutrepont, II, 73; tr. Storey (1978), p. 75.

- Fournel, p. 265.

- Fournel, p. 266.

- Fournel, p. 267.

- Fournel, p. 266; tr. Storey (1978), 75.

- Campardon, II, 108.

- Parfaict, I, 6.

- Storey (1978), p. 76; "grace and lightness" is from Campardon, I, 218.

- Parfaict and Abguerbe, III, 293.

- Parfaict and Abguerbe, III, 21.

- Described in Parfaict and Abguerbe, V, 479ff.

- The "z" and "-t-" in the title of the one of the most popular parades of 1758, Gilles garçon peintre z'amoureux-t-et rival, by Antoine Poinsinet, offer a typical illustration: see Storey (1978), pp. 80–81.

- Howarth, p. 106.

- According to the "Notice" by Georges d'Heylli (E.-A. Poinsot) in the one-volume reprint of 1881, most, if not all, of these pieces were written (or rewritten, or recorded: their status is ambiguous [see Pucci, p. 116]) by T.-S. Gueullette; four were the (again, ambiguous) work of Charles Collé. (See the next section, In the salons and private theaters.)

- Barthélemy-Christophe Fagan laid claim to the authorship of Isabelle, Grosse par vertu (and gave it a date: 1738) by publishing it in volume IV of his Théâtre (1760) (as Isabelle).

- Storey (1978), p. 79.

- "Théâtre des boulevards, ou Recueil de parades". www.archive.org. Retrieved 2016-04-20.

- Storey (1978), pp. 80.

- Léandre Fiacre (Hackney Léandre, Scene IX).

- Storey (1978), p. 80.

- Howarth, p. 108.

- See Gueullette's entry in "References" below.

- Storey (1978) gives a detailed account: pp. 77–78.

- J.-E. Gueullette, p. 63; tr. Storey (1978), p. 78.

- Howarth, p. 107.

- Howarth, p. 109.

- Lecomte (1908), pp. 81, 99, 102, 131, 145, 183, 267, and Lecomte (1910), pp. 22, 25, 46, 57, 95, 211, 234.

- Celler, p. 120; tr. Storey (1978), p. 76.

- Storey (1978), pp. 21–28.

- Storey (1978), pp. 53–54.

- Storey (1978), p. 77, n. 15

- Storey (1978), p. 41.

- Le Petit Poucet, ou Arlequin écuyer de l'ogre des montagnes (Tom Thumb; or Harlequin, Riding-Master of the Mountain Ogre, c. 1818): uncoded MS in the Collection Rondel ("Rec. des pantomimes jouées au Théâtre des Funambules et copiée par Henry Lecomte"), Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal, Paris; cited in Storey (1985), p. 12, n. 30. Storey (1985) notes that, in this era before Deburau, "the early scripts [at the Théâtre des Funambules], employ the two types [i.e., Gilles and Pierrot] interchangeably": p. 12.

- Haskell, p. 6.

- See Storey (1978), pp. 105–106, and Storey (1985), pp. 37–39, 66–68.

- See Storey (1985), especially pp. 3–151.

- Storey (1985), pp. 121, n. 24, and 111.

- See the poem "Déconvenue", translated at Pierrot lunaire.

- Samuel Glotz, as cited in Harris, p. 184.

References

- Campardon, Emile (1877). Les Spectacles de la Foire ...: documents inédits recueillis aux archives nationales. 2 vols. Paris: Berger-Levrault et Cie. Vol. I at Archive.org. Vol. II at Gallica Books.

- Celler, Ludovic (1870). Les Types populaires au théâtre. Paris: Liepmannssohn et Dufour.

- D'Heylli, Georges, ed. (1881). Théâtre des boulevards, réimprimé pour le première fois et précédé d'un notice. Paris: Edouard Rouveyre.

- Doutrepont, Georges (1926–27). Les Types populaires de la littérature française. 2 vols. Brussels: M. Lamertin.

- Duchartre, Pierre-Louis (1966) [1929]. The Italian comedy. Translated by Weaver, Randolph T. London: George G. Harrap and Co., Ltd. ISBN 0-486-21679-9.

- Fournel, Victor (1863). Les Spectacles populaires et les artistes des rues. Paris: E. Dentu.

- Gueullette, J.-E. (1938). Thomas-Simon Gueullette: un magistrat du XVIIIesiècle, ami des lettres, du théâtre et des plaisirs. Paris: E. Droz.

- Harris, Max (2003). Carnival and other Christian festivals: folk theology and folk performance. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-70191-8.

- Haskell, Francis (1972). "The sad clown: some notes on a 19th century myth". In French 19th century painting and literature: with special reference to the relevance of literary subject-matter to French painting, ed. Ulrich Finke. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Howarth, William Driver (1995). Beaumarchais and the theater. Austin: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-00751-8.

- Lecomte, L.-Henry (1908). Histoire des théâtres de Paris: Les Variétés Amusantes, 1778–1789, 1793–1798, 1803–1804, 1815. Paris: H. Daragon.

- Lecomte, L.-Henry (1910). Histoire des théâtres de Paris: Le Théâtre de la Cité, 1792–1807. Paris: H. Daragon.

- Mic, Constant (1927). La Commedia dell'Arte, ou le théâtre des comédiens italiens des XVIe, XVIIe & XVIIIe siècles. Paris: J. Schiffrin.

- Moureau, François (1984). "Appendix B: theater costumes in the work of Watteau". In Grasselli, Margaret Morgan, and Pierre Rosenberg, eds. (1984). Watteau: 1684-1721. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art. pp. 507–526. ISBN 0-89468-074-9.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Parfaict, François, and Claude Parfaict (1743). Mémoires pour servir à l'histoire des spectacles de la Foire, par un acteur forain. 2 vols. Paris: Briasson.

- Parfaict, François and Claude, and Godin d’Abguerbe (1767). Dictionnaire des théâtres de Paris … 7 vols. Paris: Rozet.

- Pucci, Suzanne R. (2006). "Watteau and theater: movable fêtes". In Sheriff, Mary D., ed. (2006). Antoine Watteau: perspectives on the artist and the culture of his time. Cranbury, N.J.: Associated University Presses. ISBN 0-87413-934-1.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Rosenberg, Pierre (1984). "Paintings". Tr. Thomas D. Bowie. In Grasselli, Margaret Morgan, and Pierre Rosenberg, eds. (1984). Watteau: 1684-1721. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art. pp. 241–458. ISBN 0-89468-074-9.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Storey, Robert F. (1978). Pierrot: a critical history of a mask. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-06374-5.

- Storey, Robert (1985). Pierrots on the stage of desire: nineteenth-century French literary artists and the comic pantomime. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-06628-0.

- Théâtre des boulevards ou recueil de parades (1756). Vol. I. Paris: Gilles Langlois.

Further reading

- Gueullette, T.-S. (1885). Parades inédites, avec une préface par Charles Gueullette. Paris: Librairie des bibliophiles.

- Spielmann, Guy, and Dorothée Polanz, eds. (2006). Parades: Le Mauvais Example, Léandre hongre, Léandre ambassadeur. Paris: Lampsaque. ISBN 2-911-82507-1.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)