Giovanni Canavesio

Giovanni Canavesio (before 1450 – 1500) was an Italian artist, documented as a "master artist" in 1450 . He was proficient in polyptychs or panels, monumental paintings, and book illuminations.[1] He was active in Liguria and southern France later in his life but documents of his activities before 1450 are missing.[2]

Career

Canavesio was born in Pinerolo, Piedmont. The earliest document about Canavesio dates to 1450, when he was recorded as a "master artist" in the Piedmontese town of Pinerolo.[2] However, there are still doubts about when Canavesio started his career.[3] Between the registration in Piedmontese in 1450 and his first documented work in 1472, Canavesio became a priest.[4] Later in his life, Canavesio is referred to as a "presbiter",[5] a priest in Latin, in almost all of the documents and signed works. In Canavesio's career as a painter, Dominicans of Taggia, a major art center, patronized his art works. He completed several wall paintings and polyptychs in their houses and chapels.[6] He was also commissioned wall paintings and polyptychs for chapter houses and refectories in the towns of Albenga, Luceram, La Brigue, Pigna, and Pornassio. Due to the chemical particularities of wall painting, he developed a seasonal schedule: panel painting in colder months and wall paintings in the warmer months, with the exception of places with mild and stable climate. For example, he finished the wall paintings of Virle and Crucifixion in Taggia in Spring.[4] In some periods of his life, Canavesio collaborates with Giovanni Baleison[7] whose signature appears with Canavesio's under the painting.[1] They divided the decoration in parts and each take their own responsibility.[1]

Works

Giovanni Canavesio appeared on documents with different orthographic names: Johannis, Johanes, de Canavexiis, Canavexi, Canavesis, or Canavesius.[4] In French studies, he is known as Jean Canavesi while in Italy he is known as Giovanni.[4] He often executed more than one commission per site. He based his work in the pictorial culture of western Piedmont.[8] Canavesio had a novel approach to paintings. He borrowed design aspects from artwork in Italy, the southern Netherlands, and northern France. He was influenced by northern Piedmont paintings which often contain vivid hues, an intense light source, and an expressionistic approach to figure drawing.[2] His style embodies pathetic and violent expression, often depicting painful, jerky gestures and movements,[9] with cruel and horrific realism at times. He developed such style from the influence of Giacomo Jaquerio, the pioneer of an independent Piedmontese school,[10] and shared his expressive beliefs to further consolidate his own conviction in art.[11] His works are also composed of Germanic style which suggests his learning in Schongauer's workshop or from artists in Colmar region.[12] Growing influence of Provençal and Niçois influence Canavesio to take approach with progressive softening of Piedmontese elements of his painting. Works created in the last few years of his career show that he was further influenced by Lombard and became closer to Ligurian art.[13]

Canavesio used distortion of anatomy and perspective for expressive purposes in creating narrative scenes that would be understood by the public,[14][15] but he was a capable artist, as shown from his tender treatment on depicting the Virgin Mary.[16]

Notre-Dame des Fontaines

Canavesio started his work in the Chapel of Notre-Dame des Fontaines, near La Brigue, with eleven displays of Virgin's life and Christ's childhood: the Nativity of the Virgin, her Presentation in the Temple, her Marriage, the Annunciation, the Visitation, the Nativity of Christ, his Circumcision, the Adoration of the Magi, the Massacre of the Innocents, the Flight into Egypt, and the Presentation in the Temple. For some paintings, he collaborated with Jean Baleison, for example in the ones of the choir that were discovered under a layer of whitewash in the 1950s.[17] The inscription of the paintings on the north wall documented Canavesio's craft and completion in October 1492 but was fallen and covered by a new one that indicated Canavesio's involvement. However, it did not articulate that all the paintings were done by Canavesio, not mentioning workshops or collaborations but the general conception of the Passion Cycle would be done by Canavesio himself.[4] The scene depicting the Virgin in the paintings of the triumphal arch would also be his collaboration with another artist.[1] Canavesio executed the nave paintings following the tradition of Italian Renaissance practices.[18] The gold and tinfoil he used now turned black due to oxidation but was restored around 1849.[4]

Passion Cycle of Christ

The depiction of different scenes in Passion Cycle demonstrates Canavesio's ability to modulate his artistic expression according to the situation needed. One of the characteristics of Notre-Dame's Cycle is the diversity: no two soldiers are dressed the same, the architectural settings vary, and even the devils are envisaged with varied anatomical structures. A wide variety of actions are depicted in a single panel and often one actor is manifesting more than one action at a time. When some scenes are described in the same setting, Canavesio endowed different architectural context. Such complexity does not exist in Canavesio's treatment in Pigna.[13] Similar to diverse motions in his figures, architectural elements also follow different perspective reasoning. Walls, arches, and pieces of furniture form a contradictory relationship with the floor on which they seem to float.[4] He departed from objective and observed reality but by exaggerating facial expressions and postures and space, he appealed to viewers' psychological state and provoked their feelings.

The Last Supper depicted by Canavesio draws distinction between apostles,[19] contrasting the sleeping St. John with Judas's abhorrent expression. Judas is the only person portrayed with messy hair and accentuated facial features such as wrinkles, veins, and protruding nose with a mole, all drawing attention to his character as traitor.

In the Arrest of Christ, the serenity of Christ's face poses a dramatic contrast to the fiendish faces of his enemies. Prominent in the crowd are the grimacing action of Judas and the tumbling Malchus with dehiscent wound spouting blood. Other soldiers and villains are also painted with grotesque features such as bared teeth and bold head, alluding to their bestial character. An opening of mouth and displaying of teeth is a feature of Canavasio's painting to indicate Christ's enemy or to show the crudeness of his enemies. Specifically, Caiaphas opens his mouth and exposes his teeth in anger; Annas with only one tooth left; and men from Ecce crowd shouting for Christ's condemnation. His delineation of a dramatic contrast between Christ's resignation and the fierce of his enemies is based on text sources, for example, in Isaiah 53:7 "He shall be led as a sheep to the slaughter, and shall be dumb as a lab before his shearer, and he shall not open his mouth", and in Jeremias 11:19 "And I was a meek lamb, that is carried to be a victim."[20]

Canavesio depicted some figures in iconography profile, which in Christian art often indicates evil characters, accentuating a caricatured meaning and also preventing veneration.[21] For example, in his painting of Last Supper, Pact, kissing Christ at the Arrest, and returning the silver coins at the Temple, Judas is always depicted in a profile view. The same treatment is used for Malchus in the scene of Christ before Annas, and John in the Arrest.

Another characteristic of Canavesio can be identified in the angularity of postures: arms and legs are bent often at right angles, especially in violent scenes.[22] Movement in opposite directions is also frequent, as can be observed in Judas leading the soldiers into the garden and Peter in his Denial, in which his head turned 180-degrees when grabbed by a soldier.[22] The psychological turmoil can be observed in the Remorse of Judas, in which his legs and head presented in profile, the latter facing left contrast to his body turned in opposite direction facing the viewer.[23]

The Entry into Jerusalem

The Entry into Jerusalem is the first panel in the cycle. It follows the traditional composition of the theme with apostles on the left and Christ on the colt in the center, and crowds on the right under the gate to Jerusalem. The details of the man on the ground, trees with men, and posture of Christ are as well conventional.[4]

The original detail appears at the man who puts a hand up on his head at the entrance gate, a motif also appears in Canavesio's first Passion Cycle at Pigna and Chieri. The similar gesture can be observed on Joseph in the Adoration of the Magi at Notre-Dame des Fontaines. Comparison with Jan van Eyck's painting The Virgin and Child with Canon van der Paele suggests the influence of Netherlandish painting.[24] Another possible reference is the representations of Moses confronting the Burning Bush, as an expression of the awareness of being in front of God.[4]

The Last Supper

This classical motif chosen by Canavesio was when Christ announces his coming betrayal and indirectly hints on Judas as the traitor. Both Christ and Judas reach their arms toward the tray in the center while Christ holds a piece of food. The traitor is revealed as well in the illustrations of Matthew (26:23)—Judas dipping his hand in the dish—and John (13:26)—Judas receiving the soup.[25] The interaction of Christ and Judas is signified by Christ extending his right hand and Judas his left. That Peter holding a knife can frequently be interpreted as his combative mood that is often presented in theatrical episode, Canavesio has no intention of showing this motif but is influenced by Savoyard Passion Cycle.

The Washing of the Feet

Besides the traditional interaction between Peter and Christ, an additional scene was added to the one in Notre-Dame des Fontaines. Judas was depicted as putting his scandals back on, alluding that he is the first one to have his feet washed. This is rather often displayed in Passion plays such as the fourteenth-century Passion Sainte-Genevieve, the fifteenth-century Passion de Semur, and Arnoul Greban's Passion.[4] His position close to the door suggests that he is about to leave and conveys a successive setting between panels. In an early-sixteenth-century miniature by Simon Bening, Judas wears the same colors as he does in Notre-Dame des Fontaines: a yellow robe with a green coat. These were colors worn by the actors of the theatrical genre of the Sottie.[19]

The Pact of Judas

Canavesio took advantage of two iconographic traditions: the representation of the Pact per scene, with Judas concluding it the priests, and the payments of the thirty silver coins. The representation of payment prevails in earlier Savoyard cycles, and the conclusion of Pact with the priests also appears in paintings in the chapel of the castle of La Manta. In the first part, Canavesio represents Judas offering to deliver Christ to the Jews while he raises his finger with a scroll issuing from his mouth and shakes hands with a priest. A devil hanging from his belt pushes Judas and holds his moneybag, in accordance with the Gospel of Luke (22:3) that says "Satan entered into Judas" just before Judas met with the priests. This detail does not appear in the other Savoyard cycle.

Canavesio's invention of combining two separate scenes into one panel influenced some early-sixteenth-century Ligurian arts. One example is Pietro Guidi who followed this treatment in his 1515 paintings at Rezzo.[26]

The Agony in the Garden

The composition of the Agony in the Garden repeats his first one at Pigna. He applied a traditional approach to put the praying Jesus in the foreground, an angel showing him the cup of sorrow and three disciples sleeping. A richness of narration is added by depicting Judas leading the troops of soldiers into the garden, foreshadowing the following scene of arrest. This appears rarely in Savoyard Passion cycles. An inspiration from Gospel simile (Luke 22:44), details of Jesus's blood sweat can be observed in both his paintings at Pigna and at Peillon.[27]

The Arrest of Christ

Canavesio combined different events into this single depiction: the kissing of Judas, the arrest, and the struggle between Peter and Malchus. The combination can be found in many pictorial sources but Canavesio added episodes like Christ heals Malchus right after his ear is cut off by Peter, St. John tries to escape but seized by a soldier.[15] Another significant detail is that Judas is barefoot when he kisses Christ but when he leads soldiers into the garden in previous panels, he wears sandals. By this detail Canavesio emphasizes Judas's awareness of standing on sacred ground when he touches his Master. In the Burning Bush of the Old Testament, Moses is also ordered by the angel to take off his shoes because "the place whereon thou standest is holy ground."[24] (Exodus 3:5).

Christ before Annas

As the setting is often represented, a troop of soldiers leads Christ to a man sitting on a throne. Canavesio chose to depict Annas as an old man as compared to his young son-in-law Caiaphas. He declares that the scene takes place at night by depicting a man holding a lantern in the foreground. Besides the main focus of the story, Canavesio adds a secondary scene that Christ is struck by an officer, as recounted in John (18:19-23). However, complementary to the event in John, Canavesio chose the officer to be Malchus, indicated by his lantern and costumes consistent with previous depictions, whose ear was cut off by Peter but healed by Christ.

Christ Before Caiaphas

The appearance of a high priest recognized by his gesture and tearing his cloth, is accounted by the Gospels: "Then the high priest rent his garments, saying: He hath blasphemed: what further need have we of witnesses?" Canavesio adds two man in civilian cloth standing on the right of Caiaphas and addressing to him besides the common means of identifying Caiaphas by his gesture.[23] Recounted by Matthew (26:59-67) and Mark (14:55-65), the two men framed false testimonies to condemn Christ.

The Flagellation

In his work of The Flagellation, Canavesio did not introduce extra settings; his composition shows a dependence on an engraving by Israhel van Meckenem.[4] As in the engraved model, Christ is afflicted by three men instead two, a traditional iconography in Piedmont and nearby areas. paintings at La Brigue and at Pigna show Christ being tied in front of a column, a less popular method than placing him with his back.[28] This modulation further stresses on the intensity of torture inflicted on Christ.

The Denial of Peter

Since there are three times of denial in Caiaphas's courtyard according to the Gospels, most pictorial cycles combined three into one with preference to the maid who first recognized the apostles.[29] The other two denials that do not agree in Gospels are often omitted, but Canavesio encompasses all four versions by introducing enough figures in his painting.

Canavesio closely followed the Gospels of Matthew and Luke in this second part of the panel of depicting Peter went out after the Denial. The independent depiction of this scene is rare but a combination of two is unique for the Notre-Dame des Fontaines.[25]

Christ before Pilate

The Christ before Pilate includes secondary events: The banners falling down before Christ despite efforts of their holders, and the addition of Pilate's wife, who stands between Christ and Pilate and tries to persuade her husband to release Christ.[30] The first one alludes to the contorted posture of their holders and their position in the foreground. The latter one is rare for the depiction of first appearance before Pilate and the only two similar compositions are found in Canavesio's painting at Pigna and the work of Pietro Guidi at Montegrazie, who was influenced by Canavesio.

Christ Tormented

The tormented scene depicted in Notre-Dame is the one during the night when Christ was tortured after his arrest. The inclusion of diversity and intensity stresses the severity and extent of Christ's suffering. The soldiers are engaged in various motions, one moving clockwise from the lower left, one blowing a horn and making an insulting gesture, and the others torturing Christ by pulling his beard and hair, hitting and insulting him. One man who sits in front of Christ one the right is depicted as choking himself on the neck to stimulate more spittle to spit on Christ.[4]

Christ before Herod

In this painting, the king is characterized by his crown and scepter.[29] Canavesio renovated way of presenting by including two women at the balcony, one of whom wearing a crown and making a gesture is the queen, Herodias, and the other is her daughter. Canavesio used this idea as early as his first Passion cycle at Pigna.[15] The man in the pink hood recurs in many other panels. He is also present when Judas gives the money to the Temple, hinting at the king's link with the sect. His reappearance throughout the cycle paintings stresses his involvement in Christ's sufferings and death.

The Mocking of Christ

This episode is delayed until Christ met Herod, who witnesses the torture from a balcony. Also contradictory to the Gospels is to have Christ wearing a scarlet robe, relative to the crowning with thorns. His original clothes rest on the parapet, alluding to the motion of undressing and dressing. Emphasis on architectural elements is achieved through details of a mate at the left of the painting, going up the staircase with a bucket of water, who appears in the next panel with a cloth in her hand. The technique is linked to a Savoyard precedent, a depiction at the chapel of San Fiorenzo at Bastia.

The Crowning with Thorns

The composition of the Crowning with Thorns derives from Israhel's print. In the print, a man is handing the reed to Christ but Canavesio chose to delineate on insulting movement and gestures that would add more brutality into the abuse. The presence of Pilate is also an indication of his involvement in the torment and that the scene is taking place in his palace.

Ecce Homo

Canavesio follows Israhel's print to present Christ as naked on this panel. The prominent wound on his body could allude to a second time Flagellation which though does not follow the Gospel of John (19:4-7). The Pharisee with the pink hood reappears in this panel, who demand Christ's death, and the inclusion of the monkey sitting in the foreground is also a derivation from Israhel's Ecce Homo.

The Remorse of Judas

This scene rarely appears in illustrations but Canavesio also included Pharisee, a Temple's principal official in the pink hood, and depicted his dealing with Judas, building a link between each different settings. The left side of the composition shows Christ led by a soldier, a label of fleshing out the Gospels, which also functions as a transition to the next panel. Canavesio innovated this representation of connecting two moments of the trial; He first tested it out at Pigna, and used it at Notre-Dame to further illustrate the suffering of Christ, and a succession of tortures.

The Suicide of Judas

The iconography is usually depicted as hanged, with a devil pulling his soul out of his burst abdomen. Canavesio includes all elements obvious in earlier Piedmontese painting, like the opened stomach, the devil, and the small soul featured with Judas's face pulled out from his body.

Pilate Washing His Hands

Canavesio relied heavily on Israhel's composition for his painting of Pilate Washing His Hands. He kept some elements from the print and enhanced the depth of his depiction by showing the shouting man and the man holding cross in the background that alludes to the making of the cross. With a narration in the men carrying the cross away and the figures about to leave, Canavesio builds a bridge to connect to the next scene, the Way to Calvary.

The Way to Calvary

Cavavesio built the composition of the Way to Calvary based on Israhel's print. He keeps a portrait of Simon of Cyrene carrying the cross for Christ but modifies his costumes. He also added two thieves that later reappear in the Crucifixion.

The Nailing to the Cross

The iconography follows the late Middle Ages depiction. Christ was nailed to the cross on the ground. Since the holes are made on the cross beforehand and are found to be too far apart when Christ is laid on it, his body is stretched to reach the hole. As a result of the stretch, the bones of the body are clearly shown and countable. The white robe Christ has been wearing falls to ground, relating to the stripping of his garment in the past and reopening of his wounds in the future.

The Crucifixion

The complexity of narration of Notre-Dame's Passion reaches climax in the Crucifixion. The composition is filled with secondary figures and events which are tradition and often featured in Savoyard Passion cycles. One is the breaking of thieves’ bones as described in the Gospel of John (19:32). The diluted vermilion fills in the hollow knife, allowing an imprint of red marks on the legs. Another feature is soldiers rolling dice, fighting for Christ's seamless garment. The game of dice is embodied with devil discord, and murderer in Passion plays.

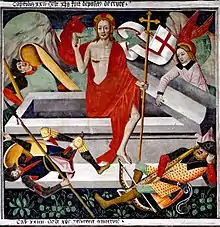

The Deposition, the Entombment, and the Resurrection

Canavesio included no additional narrative elements than traditional iconography in representing three scenes.

The Descent into Limbo

It is an uncommon iconography to have the good thief Dismas standing behind Christ. It only appears in a few Italian works of the 14th and 15th century. Canavesio encourages the viewer to draw attention on Dismas by the inscription of his name. John the Baptist is the only patriarch to be haloed, emphasizing he is the only human being who died as a Christian saint.

Influence from Savoyard and Piedmontese pictorial tradition

The gestures and distorted facial features of Canavesio's figure pointed to the echo of Jaquerian style in Ranverso's Way to Calvary.[13] In both paintings, there are men blowing trumpets with similar human physiognomy to convey an evil character of the figure.[11] Such features can be seen throughout Savoyard monumental paintings, specifically between Jaquerio and Canavesio' s period. The Mocking of Christ and Crowning with Thorns painted by another Savoyard painter, Guglielmetto Fantini, shows the same strong contrast between Christ's tranquil composure and the ferocious violence of his torturers.[1]

The similarities can also be seen from Peter's pose in the Denial, a Piedmontese art painted in the chapel of castle of La Manta fifty years before the one in La Brigue. The apostle is depicted as warming himself while denying Christ in the same manner illustrated at Notre-Dame. The feelings of unease, tension, and pain in Canavesio's painting can be compared to Giovanni Beltrami's martyrdom of Bartholomew, in which the right foot of the saint is twisted, reflecting Canavesio's manipulation of human bodies.

As well related to the earlier Piedmontese artistic traditions are the diversity in Chavesio's choice in gestures, tools, costumes, and backgrounds. The Passion cycle in the baptistery of Chieri also presents the viewer with no two military armors identical and with a wide range of fancy decorative apparels for Jews. A variety of weapons, such as switches, thick sticks of wood, a leather belt, and even braids of garlic and onions, are illustrated in Mocking of Christ and Crowning with Thorns. The complexity in the scene setting finds its correspondence again in murals in the castle of La Manta, for example pact of Judas and Last Supper. Comparable to the Crucifixion in Notre-Dames des Fontaines is Turin's Museo Civico, which has the same horror and void appealing.[4]

Narration of the Cycle

In his depiction of the Passion cycle, Canavesio not only chose to catch each figure in motion, but also to place each movement consistent with the flow of the story-telling. The emphasis on Judas's feet in the Washing of the Feet and then in the Pact, for example, stresses the sequence of the events, bringing out a kinetic effect and a sensual conjunction. The following Agony in the Garden portrays his arm as reaching out and targeting the Christ. Then, the scene narrates from left to right, portraying Judas's kissing and betrayal of Christ. Later he can be seen moving still from left to right with contorted posture that alludes to the unease of his mind, leading to his final suicide where his soul is pulled out in a direction that corresponds with the cycle's narration.[31]

The left to right movement not only applies to Judas's movement, but also to Christ, parallel to the edge of the painting, as he proceeds in the Entry into Jerusalem, the Way to Calvary, and the Descent into Limbo. In Jesus's trials, soldiers also lead Christ from left and advance to the authority on the right. The judges are arranged diagonally with a three-quarters depiction that features on more comprehensive view than profile drawings, deeper space illusion, and an open end on the right that allows the continuation to the next panel.[4]

Figures' postures complemented with gestures and glances further strengthen the left-right narration. For example, in the Arrest of Christ, the bearded man at left captures the viewers’ eye, which is then directed to Judas by their joined hands. Judas kisses Christ who reaches his arm to Malchus whose hair is being grabbed by Peter at the very right. Peter ends this chain from left to right and through his scabbard, viewers' eyes exit the panel and continue to the next. The similar delivery can be found in most of the panels, in which figures on the left would introduce the view to the right scene by their glance, gestures or postures.[4]

In some panels, figures are cut by the frame or under doorways to emphasize the flowing narration and encourage the viewer to image that action of connection. In the Crowning with Thorns, a man with a white beard and a red turban is standing under an arch with his head turned to the right. The scale and spatial location of the man and the opening are consistent with the next scene Ecce Homo. Thus, the man witnesses the events taking place on the porch where another man pushes Christ and looks back to the preceding panel. The superimpose of diaphragm arch and partial elimination by frame happens to figures of all importance, including Christ, who is shown blocked by the left frame in the Romorse of Judas.[4]

In the Denial of Peter, a soldier stands at the wall that separate the interior and exterior space. The depiction of him turning to the left while pointing his sword to the right serves to connect two successive scenes. This panel is also linked to the previous one as the maid who points to Peter with her right hand while pointing her left hand to the indoor where Christ is located in the previous panel.[32] This technique is used to emphasize the contiguity of successive events; on the other hand, the discontinuity of settings is stressed by a man standing at the extreme right side who was but by the frame.

Another technique that Canaveso employs to emphasize continuity is to depict same character in different settings with same costumes. A man recognized by his clothes with a yellow hat and a hammer tucked in his belt leads Christ before Herod, before Pilate Washing His Hands, and on the Way to Calvary, and finally nails Christ's feet to the Cross using his hammer.[22] Two other characters easily recognized by their costumes keep reappearing in four panels. Different postures complement the recurrence of the same figure in the effectiveness of quick transition, which can be seen in the depiction of Judas when he exits from the Washing of the Feet and proceeds to the Pact. Objects are as repetitively depicted for the same function, such as the cross in the Way to Calvary, and in the Nailing, which is occupied and orientated in the same way, contributing to the sequential connection of two scenes.

Canavesio also develops a technique to balance the left to right movement of his panel drawings to provide rhythm and assure decent comprehension of each scene. The most prominent he uses is to place Christ in the center and to direct all the gestures and focus to this main character. In some paintings, the effect is achieved by placing figures in the foreground with their backs turned to the viewer or by having a main character to designate the direction other characters should look at. In Canavesio's paintings, gestures and glances serve to tell the story, to keep the flow of successive settings, and to push viewer's eyes through the panel. Especially in the Crucifixion which viewer are expected to scrutinize, glances and gestures of figures feature a tumultuous scene and anchor viewers' eyes on this panel.

Though lighting effect is not strong on objects depicted in conflicting perspectives, some panels of paintings still have a clear light definition such as the shadow cast on the wall by Christ and the apostles and most architectural elements in the Last Supper, and by figures and weapons in the Ecce Homo but with a different direction, and by Judas in his Remorse. The lighting follows a fifteenth century tradition in architectural space for the main light source comes from the entrance door on the west wall.[23] The light depicted on the Last Supper which is displayed at the entrance also symbolically represents the light from the entrance.[4]

Use of color

In the panel paintings of Notre-Dame des Fontaines, Canavesio utilizes bright colors with sharp contrast that form an extremely bold palette; the most noticeable are yellow and red. Pigments are applied to the flat area outlined by thick black color. The thickness of the outline also accentuates levels of shading. There is little subtlety in his use of colors, so all figures are easily readable even from far away. This might be a result of the different lighting condition in the church in fifteenth century when its ceiling was not yet raised and a few windows were open, and the only light source comes from the narrow window above the Suicide of Judas.[12]

Size of the building is also a consideration for Canavesio. For the cycle at Peillon which is painted on a much smaller scale and restricted space, Canavesio employed a more dull color choices since viewers approach the paintings from a closer distance. Therefore, the readability of paintings at La Brigue is reasonably enhanced by a choice of brighter colors and black outlines of colored zones. However, there is still a possibility that the bright color can be a result of earlier restorations.[4]

Sources of the Passion Cycle

Canavesio used principal sources from Grobe Passion engraved by the German artist Israhel van Meckenem and related anonymous series as reference to his compositions at the Notre-Dame des Fontaines, and at Pornassio. Prints from famous artists were commonly referred by contemporary artists on their manuscript illustration, panel and wall paintings, enamel, and many different art forms. He drew his inspirations from German and Netherlandish prints;[15] from a woodblock in the Edmond de Rothschild collection, he borrowed elements to depict the grassy garden, Judas, soldiers entering through a door,[15] position of a sleeping apostle, and St. John. He used the woodprints no more than ten years after they were engraved, showing his attraction to northern art, a central definition of his style, and his aggiornamento to the works. Canavesio was most influenced by Netherlandish art and Piedmontese artistic landscape; such link can be observed in comparison of the Last Judgment at Notre-Dame des Fontaines and the Eyckian panel now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.[9]

Canavesio's use of print sources is relative. Nine panels show influence from Israhel van Meckenem from which eight out of twelve Passion series prints were used. The degree of borrowing vary from different panels and details can be seen in figures, motifs, or the entire composition. In some detail treatment, Canavesio also heavily borrowed ideas from minor sources.[4]

Due to limitations of wall paintings, Canavesio encompasses number of figures and settings from detailed engraving from his sources selectively. For example, he left out the fruits in front of the monkey in Ecce Homo, changed props like book and walking sticks of apostles, and modified architecture settings in several traditional motifs. The scale of figures often appears larger in Canavesio's printing than the original engravings.[4]

Documented activities

1472, he received commission in Ligurian town of Albenga to paint a Maestà(now lost) for the church of Oristano in Sardinia, after which he became active in western Liguria and the region of Nice[2] and all documents and inscriptions on work since then bear his title presbiter.[33]

1477, he did a heraldic painting on the facade of Palazzo Vescovile. This is his first dated and existing work without his signature but unanimously attributed to him.

1482 April, he painted a Crucifixion in the chapter house of Dominican convent in Taggia, but the work is also not signed yet attributed to him with no doubt.[4]

1482 October, he finished his first surviving Passion cycle in fresco at San Bernardo in Pigna.

1487 June 3, he signed and date a painting(now lost) in the parish church of Virle, not far from Pinerolo.

1491 March 3, he finished an altarpieve for the pilgrimage chapel of Notre-Dame des Fontaines at La Brigue.

1492 October 12, he did several paintings for this pilgrimage chapel and finished its decoration.

1499 March 20, he completed a polyptych for Pornassio, which is now in the parchish church of Berderio Superiore.[34]

1500 January, he finished the polyptych dedicated to St.Michael in the parish church of Pigna.

References

- De Floriani, Anna (1992). La pittura in Liguria. Genova : Tormena. ISBN 8886017022.

- Terminiello, Giovanna. "Canavesio, Giovanni". Grove Art Online.

- Romano, Giovanni (1994). Tra la Francia e l'Italia. Electa. p. 188. ISBN 2-7118-3116-7.

- Plesch, Véronique (2006). Painter and Priest. Notre Dame, Indiana 46446: University of Notre Dame. pp. I. ISBN 0-268-03888-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Hood, William (1993). Fra Angelico at San Marco. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300057342.

- Bartoletti, Massimo (2012). Il convento di San Domenico a Taggia. Genova: Sagep. ISBN 978-8863731927.

- Terminiello, Rotondi. "Baleison Giovanni". Grove Art Online.

- Benezit, E (2006). Dictionnaire des peintres. Paris : Gründ. ISBN 2700030702.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Roques, Marguerite (1963). Les apports néerlandais. Bordeaux. Union française d'impression. p. 199.

- Weber, Siegfried (1911). Die begründer. Strassburg J.H. Ed. Heitz. pp. 18–19.

- Griseri, Andreina (1965–1966). Jaquerio. Torino, Fratelli Pozzo. p. 98.

- Fulcheri, Michelangiolo (1925). Giovanni Canavesio. Torino : Giovanni Chiantore. pp. 39–44.

- Rossetti Brezzi, Elena (1964). Precisazioni sull'opera di Giovanni Canavesio.

- Bertea, Ernesto (1984). Pitture e pittori del Pinerolese. Forni. p. 58. ISBN 9788827124437.

- Roques, Marguerite (1961). Les peintures murales. Paris: A. et J. Picard.

- Thevenon, Luc (1990). La Brigue. Nice : Serre. ISBN 2864101459.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Thevenon, Luc (1983). L'art du moyen-age. Editions Serre. p. 26. ISBN 978-2864100478.

- Stefanaggi, Marcel and Callede, Bernard(1974), Report 95B

- Mellinkoff, Ruth (1993). Outcasts. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520078152.

- Marrow, James H (1979). Passion iconography. Kortrijk, Belgium : Van Ghemmert Pub. Co.

- Demus, Otto (1976). Byzantine mosaic decoration. New Rochelle, New York : Caratzas Brothers, Publishers. ISBN 0892410183.

- Avena, Benoît (1989). Notre-Dame des Fontaines. Borgo San Dalmazzo : Ed. Martini.

- Garnier, François (1982–1989). Le langage de l'image au Moyen Age. Paris : Léopard d'or. ISBN 2863770144.

- Panofsky, Erwin (1953). Early Netherlandish painting, its origins and character. Cambridge, Harvard University Press.

- Schiller, Gertrud (1971). Iconography of Christian art. Greenwich, Conn., New York Graphic Society. ISBN 0821203657.

- Calzamiglia, Luciano (1999). I Guido da Ranzo. Imperia : Dominici.

- Caulibus, Jean (1958). Méditations sur la vie du Christ. Paris : Ed. franciscaines.

- Plesch, Véronique (2004). Le Christ peint. Chambéry : Société savoisienne d'histoire et d'archéologie.

- Réau, Louis (1955–1959). Iconographie de l'art chrétien. Paris, Presses universitaires de France.

- Roy, Émile (1974). Le mystère de la Passion en France du 14e au 16e siècle. Genève : Slatkine Reprints.

- Gandelman, Claude (1991). Reading pictures, viewing texts. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253325323.

- Falvey, Kathleen (Summer 1977). "The First Perugian Passion Play: Aspects of Structure". Comparative Drama. 11 (2): 127–138. doi:10.1353/cdr.1977.0014. JSTOR 41152712. S2CID 190232501.

- Hood, William. Fra Angelico at San Marco. p. 9.

- Parente, Elisabetta. Il polittico con la Madonna e santi di Giovanni Canavesio.