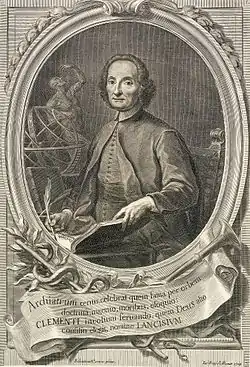

Giovanni Maria Lancisi

Giovanni Maria Lancisi (26 October 1654 – 20 January 1720) was an Italian physician, epidemiologist and anatomist who made a correlation between the presence of mosquitoes and the prevalence of malaria. He was also known for his studies about cardiovascular diseases, an examination of the corpus callosum of the brain, and is remembered in the eponymous Lancisi's sign. He also studied rinderpest during an outbreak of the disease in Europe.

Giovanni Maria Lancisi | |

|---|---|

Giovanni Maria Lancisi | |

| Born | 26 October 1654 |

| Died | 20 January 1720 (aged 65) |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Alma mater | University of Rome |

| Known for | malaria cardiovascular diseases |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | medicine anatomy |

Biography

Giovanni Maria Lancisi (Latin name: Johannes Maria Lancisius) was born in Rome. His mother died shortly after his birth and he was raised by his aunt in Orvieto. He was educated at the Collegio Romano and the University of Rome, where by the age of 18, he had qualified in medicine. He worked at hospital of Santo Spirito in Sassia and trained at the Picentine College, Lauro. In 1684 he went to Sapienza University and held the chair of anatomy for thirteen years. He served as physician to Popes Innocent XI, Clement XI and Innocent XII. Clement XI gave Lancisi, the anatomical plates of Bartolomeo Eustachius; made originally in 1562 and had been forgotten or lost in the Vatican Library. Lancisi edited and published them in 1714 as the Tabulae anatomicae.[1]

Lancisi studied epidemiology, describing the epidemics of malaria and influenza. He published De Noxiis Paludum Effluviis (On the Noxious Effluvia of Marshes) in 1717, in which he recognized that mosquito-infested swamps are the breeding ground for malaria and recommended drainage of these areas to prevent the disease. He also published extensively on cardiology, describing vegetations on heart valves, cardiac syphilis, aneurysms and the classification of heart disease.[2] His landmark De Motu Cordis et Aneurysmatibus was published posthumously in 1728, edited by Pietro Assalti who also conducted the autopsy of Lancisi and identified his death as being caused by a duodenal infarction.[3]

Early in the 18th century, Lancisi had protested the medieval approaches to containing rinderpest in cattle by stating that "it is better to kill all sick and suspect animals, instead of allowing the disease to spread in order to have enough time and the honour to discover a specific treatment that is often searched for without any success".[4] Lancisi who made the first breakthrough in the control of rinderpest (Lancisi, 1715), a procedure that was later adopted by Thomas Bates.

However, Lancisi also erred, as he disputed the work of Giovanni Cosimo Bonomo (1663-1696), his contemporary, who had correctly identified the cause of scabies as a parasite.[5] Lancisi however felt scabies was of humoral origin.[3] Because of Lancisi’s powerful position and, because previous scientists like Galileo Galilei had fallen into disgrace, Bonomo was silenced and his discovery was forgotten until the modern era.[6]

Studies on the brain and the soul

Lancisi described the corpus callosum as the "seat of the soul, which imagines, deliberates and judges."[7] His Dissertatio Physiognomica provided the supporting argument in 1713. He opposed alternative locations of the soul as hypothesized by others, such as the centrum ovale, by Andreas Vesalius, and the pineal gland, by René Descartes. He hypothesized that the longitudinal striae (later named in his honor as the "striae lancisi" or "nerves of Lancisi") were the conduit between the anterior location of the soul, and the posterior location of sensory organ functions, both within the corpus callosum.[8]

Notes

- Firkin, Barry G.; Whitworth, Judith A. (1996). Dictionary of Medical Eponyms (2nd ed.). Parthenon. p. 225. ISBN 1-85070-477-5.

- Klaassen, Zachary; Chen, Justin; Dixit, Vidya; Tubbs, R. Shane; Shoja, Mohammadali M.; Loukas, Marios (2011). "Giovanni Maria Lancisi (1654-1720): Anatomist and papal physician". Clinical Anatomy. 24 (7): 802–806. doi:10.1002/ca.21191. PMID 21739476. S2CID 205536323.

- Paleari, Andrea; Beretta, Egidio Paolo; Riva, Michele Augusto (2021-03-01). "Giovanni Maria Lancisi (1654–1720) and the modern cardiovascular physiology". Advances in Physiology Education. 45 (1): 154–159. doi:10.1152/advan.00218.2020. ISSN 1043-4046. PMID 33661047.

- Pastoret, Paul-Pierre; Yamanouchi, Kazuya; Mueller-Doblies, Uwe; Rweyemamu, Mark M.; Horzinek, Marian; Barrett, Thomas (2006), "Rinderpest — an old and worldwide story", Rinderpest and Peste des Petits Ruminants, Elsevier, pp. 86–VI, doi:10.1016/b978-012088385-1/50035-6, ISBN 978-0-12-088385-1, retrieved 2021-05-18

- Roncalli RA (July 1987). "The history of scabies in veterinary and human medicine from biblical to modern times". Vet. Parasitol. 25 (2): 193–98. doi:10.1016/0304-4017(87)90104-X. PMID 3307123.

- Ng, Kathryn (2002). "The affair of the itch: discovery of the etiology of scabies". In Whitelaw, W.A. (ed.). The Proceedings of the 11th Annual History of Medicine Days. University of Calgary. pp. 78–83.

- Andrew P. Wickens, A History of the Brain: from Stone Age Surgery to Modern Neuroscience (2014)

- Marco Catani, Stefano Sandrone, Brain Renaissance: From Vesalius to Modern Neuroscience (2015) p. 85.

References

- Gazzaniga, Valentina (2003). "Giovanni Maria Lancisi and urology in Rome in early modern age". J. Nephrol. 16 (6): 939–44. PMID 14736023.

- Mantovani, A; Zanetti R (1993). "Giovanni Maria Lancisi: De bovilla peste and stamping out". Historia medicinae veterinariae. 18 (4): 97–110. PMID 11639894.

- Fye, W B (1990). "Giovanni Maria Lancisi, 1654–1720". Clinical Cardiology. 13 (9): 670–1. doi:10.1002/clc.4960130917. PMID 2208828.

- McDougall, J I; Michaels L (1972). "Cardiovascular causes of sudden death in "De Subitaneis Mortibus" by Giovanni Maria Lancisi. A translation from the original latin". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 46 (5): 486–94. PMID 4570450.

- Michaels, L (February 1972). "Pain of cardiovascular origin in the writings of Giovanni Maria Lancisi". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 106 (4): 371–3. PMC 1940389. PMID 5061134.

- "Giovanni Maria Lancisi (1654–1720)- Cardiologist, forensic physician, epidemiologist". Journal of the American Medical Association. 189 (5): 375–6. August 1964. doi:10.1001/jama.1964.03070050041016. PMID 14160512.

- Pazzini, A (April 1954). "[To Giovanni Maria Lancisi on three hundredth anniversary of his birth.]". Athena; Rassegna Mensile di Biologia, Clinica e Terapia. 20 (4): 177–80. PMID 13181790.

External links

- Preti, Cesare (2004). "LANCISI, Giovanni Maria". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Volume 63: Labroca–Laterza (in Italian). Rome: Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana. ISBN 978-8-81200032-6.

- (in Latin) Dissertatio historica de bovilla peste, ex Campaniae finibus anno 1713, Rome, 1715.

- Dissertatio historica de bovilla peste (1715)