Giovanni dal Ponte

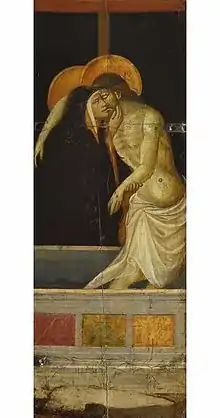

Giovanni dal Ponte (1385 – c. 1438 in Florence) was a Florentine minor master painter of the late-Gothic period, known as one of the greatest minor masters contemporary to Masaccio. He is known by Giorgio Vasari as dal Ponte, a name derived from the location of his studio at the Piazza di Santo Stefano a Ponte.[1] Many other documents cite his name as Giovanni di Marco. After joining the Arte dei Medici e degli Speziali in 1410 and the Compagnia di S Luca in 1413, dal Ponte opened his studio in the late 1420s and hired Florentine painter Smeraldo di Giovanni as his assistant.[2] Smeraldo was hired after dal Ponte was imprisoned in 1424 due to failure to repay his debts, with the intention that Smeraldo would manage the logistical aspects of the workshop in addition to his artwork. Dal Ponte used his craftsmanship to create not only Panel paintings, but also frescoes and decorations for small objects. Dal Ponte's work is considered to be of the Late Gothic style, though he assimilated the stylistic preferences of his contemporaries; Lorenzo Monaco, Masaccio, and Lorenzo Ghiberti served as his primary influences.

Early work

Giovanni dal Ponte established rapport as an artist by creating marriage chests, Cassone or forzieri, for Illarione dei Bardi in 1422. Following the positive reception of his work for Illarione, dal Ponte was commissioned by Giovannozo and Paolo Biliotti in 1427 and Bardo di Francesco de' Bardi in 1430 to create similar pieces.[3] While he was best known for these marriage chests, he also painted candlesticks and banners, or drappelloni, and domestic tabernacles, cassoni or colmi, and in fact is noted as an outstanding talent in the latter form.[4] In 1427, Giovanni gilded candlesticks for the Bigallo, a lay charitable organization associated with Santa Maria Nuova. From 1429 to 1435, dal Ponte became involved with larger projects, including several fresco cycles at Santa Trinita. The frescoes included scenes from the life of Saint Paul in the Cappella d'Abbaco and Saint Bartholemew and Saint Peter's martyrdom in the Cappella Scali. Dal Ponte designed several Triptychs in 1434; the two most famous are his two versions of the Annunciation, created in 1430 and 1435, which are located at Santa Maria in Rosano and the Pinacoteca Vaticana in Rome, respectively.[5] In 1434, Giovanni painted a small altarpiece for the Oratorio di S. Eugenio a Pugliano. The altarpiece depicts the Annunciation with Saints Eugenio, Benedict, John the Baptist and Nicholas, and still resides in the church. The altarpiece identifies its patron as Abbess Caterina da Castiglionchio, a member of the powerful Castiglionchio family of lords.

Partnership with Smeraldo di Giovanni

In 1424, dal Ponte was imprisoned because he had failed to repay his debts. In 1427, after finishing his prison sentence and seeking financial solvency, dal Ponte decided to initiate a collaboration with Smeraldo di Giovanni, an older, experienced painter who had worked with Ambrogio di Baldese in 1403.[5] While Giovanni sought out the partnership for fear of financial ruin, Smeraldo did so because he was receiving too few commissions.[3] The artists probably had not worked together prior to the inception of their workshop collaboration. The coordination took the form of a limited partnership.[3] Dal Ponte earned sixty-five percent of the shop's profits, with the remainder going to Smeraldo, though dal Ponte was responsible for the shop's rent payments, while Smeraldo was not, making the agreement fairly equitable. The structure of their arrangement parallels that of Bicci di Lorenzo and Stefano d'Antonio, in the sense that the greater painters received a much higher rate of compensation than their assistants. In fact, it is thought likely that Giovanni and Smeraldo's arrangement created the opportunity for Bicci and Stefano's partnership of the same nature.[3] Their workshop was adept at many forms of craft, including the creation of Giovanni's reputation-making marriage chests as well as banners, though it appears that at the beginning, the shop was best known for its cassoni. It was staffed by many artisans employed on a temporary basis, which allowed the workshop flexibility as its ornamental chest business accelerated toward the end of the 1420s. For example, of the artisans hired to assist in the workshop in 1427, six were woodworkers (the shop also employed blacksmiths, goldsmiths, and other painters).[3]

The painters shared their commissions and tools, though dal Ponte was ultimately responsible for the management of the workshop. This agreement appears to have been acceptable to both artists, as they renewed their contract in 1431.[3] Although the two artists shared commissions and tools with one another, their work appears to have been carried out autonomously through the division of labor. For example, each artist would oversee the execution of one work, as was done when Giovanni oversaw a forzieri for Giovannozo and Paolo Bigliotti while Smeraldo oversaw a forzieri for Matteo degli Strozzi.[3]

Smeraldo provided a significant contribution to the workshop's success when he obtained the commission to fresco the Cappella d'Abbaco at Santa Trinita (c. 1432). Unlike Giovanni, Smeraldo had been trained in fresco at the beginning of his career and had helped to design frescoes at Orsanmichele in 1403 while assisting Ambrogio di Baldese.[3] The officials determining the Santa Trinita commission were likely the same officials who had led the Orsanmichele decoration, giving Smeraldo a leg up in securing the commission. After the partners' success in the Cappella d'Abbaco, they were asked to decorate the nearby Cappella Scali (c. 1434). Giovanni's miniaturist style can be seen in these frescos, carrying over from his work on cassoni and tabernacles.[3] There is also a record of the two artists having decorated the nearby Cappella Ficozzi. During these endeavors, Giovanni was no longer considered the sole master of the workshop, as each artist abandoned personal projects to join together on the frescoes.[3] This project seems to mark the transition from a financially motivated partnership to a durable artistic collaboration. Unfortunately, dal Ponte insisted on retaining sole ownership of the workshop, which caused its continual mismanagement. The bottega's financial health was in question primarily because of delinquent patrons, though Giovanni resisted court involvement, which could have compelled such patrons to pay for their purchases.

After Giovanni's death in 1437-1438, Smeraldo retired and no longer continued artistic activities.[3]

Marriage Chests (Cassoni or Forzieri)

Dal Ponte was well-known for his talent in decorating cassoni, or marriage chests, which peaked in popularity between the 1430s and 1440s.[3] Cassoni often depicted scenes exemplifying the joys of a young bride, particularly through scenes of couples in gardens (the Garden of Love), famous couples from mythology or folklore, and the Judgement of Paris.[3] While religious themes were not absent from these artworks, they tended to be layered under modern interpretation.[4] Cassoni commanded prices on par with those for some altarpieces, with parity between the pay for minor and major masters. In 1422, dal Ponte received 45 fiorini for forzieri for Illarione dei Bardi to commemorate his niece Costanza's wedding to Bartolomeo d'Ugo degli Alessandro.[4] In 1427 he received 30 fiorini for two forzieri for Giovanozzo and Paolo Biliotti for their sister's marriage to a member of the Gondi family.[4]

Giovanni and members of his workshop created one of the best known cassoni, depicting the Seven Liberal Arts. The arts, Astronomy, Geometry, Arithmetic, Music, Rhetoric, Dialectic and Grammar, are accompanied by their Greek epitomes, Archimedes, Pythagoras, Tubal Cain, Cicero, Aristotle, and Donatus.[4] They also created several depicting lovers in a garden, a popular theme for such pieces at the time, such as Four Couples in a Garden at the Museé Jacquemart-Andreé in Paris and Four Worthies in the National Museum of Krakow.[4]

Impact of the Contado

Giovanni painted several of his works in the Florentine contado, or countryside, which impacted his style. Painters in the contado were encouraged to be conservative in style by their patrons, who prioritized craftsmanship and efficiency over artistic innovation. The differences in economics of the Florentine city and its contado account for a great deal of the differences between the Renaissance’s minor and major masters. Very few, if any major masters painted in the contado, leaving the region in the control of the minor masters. While the minor masters simply were never commissioned to paint the high altarpieces of Florentine churches, their craftsmanship was revered in the contado, where they were sought after.[4] In these ways, while the contado is generally understood to contain “minor works,” this terminology is deceptive due to the significant works of minor masters located there. Moreover, the minor masters were often able to obtain compensation similar to what a major master might garner in the same location. In order to support themselves, the minor masters were more reliant on less revered art forms, such as the production of small tabernacles and other small crafts. Furthermore, the minor masters tended to practice a more conservative style, allowing the major masters to take bold artistic risks in major cities while they created more traditional works. As artists bridging the gap between the early and high Renaissance styles, the minor masters connected the Trecento and the Quattrocento and Renaissance, incorporating some of the major masters’ innovations while remaining firmly planted in more conservative style. Perhaps if dal Ponte had been considered a major master, he would have had the opportunity to take greater risks in his craft.

References

- Vasari, Giorgio. Lives of the Artists. London: Folio Society, 1993.

- Howe, Eunice, D. "Giovanni dal Ponte". Oxford Art Online.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - EVEN, Y. M. (1984). Artistic Collaboration In Florentine Workshops: Quattrocento (Order No. 8427386). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (303285782).

- Bailey, H. E. (1992). The other renaissance: Florentine painting in the shadow of Masaccio (Order No. 9316305). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (303964947).

- Shell, C. (1972). Two triptychs by giovanni dal ponte. The Art Bulletin, 54(1), 41.

External links

Media related to Giovanni dal Ponte at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Giovanni dal Ponte at Wikimedia Commons