Giuliana Stramigioli

Giuliana Stramigioli (Italian: [dʒuˈljaːna stramiˈdʒɔːli]; 8 August 1914 – 25 July 1988) was an Italian business woman, university professor and Japanologist.

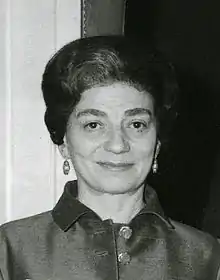

Giuliana Stramigioli | |

|---|---|

Giuliana Stramigioli in the 1980s. | |

| Born | August 8, 1914 |

| Died | July 25, 1988 (aged 73) Rome, Italy |

| Citizenship | |

Biography

After graduating at the University of Rome in 1936 under the guidance of Giuseppe Tucci, Stramigioli arrived in Japan as an exchange student, specialising at Kyoto University in Japanese Language and History of the Art of Buddhism.

Having returned to her homeland after two years, she started teaching at the University of Naples, but went again to Japan to take up a scholarship offered by the Kokusai bunka shinkōkai (today Japan Foundation).

Between 1936 and 1940, she worked as a free-lance journalist, collaborating with Italian newspapers such as Gazzetta del Popolo and il Giornale d'Italia while writing an account of her travels to Korea, and a reportage about northern Japan and the Ainu people. During World War II Stramigioli served at the Italian Embassy in Japan and then at the Italian Institute of Culture.

At the end of the conflict, she started teaching Italian at Tokyo University of Foreign Languages. In 1948 she founded her firm, Italifilm, devoted to the importation of Italian movies into Japan. Through her activities, movie fans there came to know Italian Neorealism with works like Rome, open city, Bicycle Thieves, Paisan, and others.[1]

Moreover, it is Stramiglioli who recommended Kurosawa Akira's Rashomon (1951) to the Venice Film Festival, where the movie was awarded the Golden Lion prize. In his autobiography, Kurosawa wrote:[2][3]

I arrived home depressed, with barely enough strength to slide open the door to the entry. Suddenly my wife came bounding out. “Congratulations!” I was unwittingly indignant: “For what?” “Rashomon has the Grand Prix.” Rashomon had won the Grand Prix at the Venice International Film Festival, and I was spared from having to eat cold rice. Once again an angel had appeared out of nowhere. I did not even know that Rashomon had been submitted to the Venice Film Festival. The Japan representative to Italiafilm, Giuliana Stramigioli, had seen it and recommended it to Venice. It was like pouring water into the sleeping ears of the Japanese film industry. Later Rashomon won the American Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film.

Stramigioli returned home permanently in 1965, where she kept the Professorship of Japanese Language and Literature at La Sapienza University of Rome until 1985.

She was, with Fosco Maraini among others, a founding member of the AISTUGIA – the Italian Association for the Japanese Studies.[4]

Honours

- 1982 Kunsantō hōkanshō, Order of the Precious Crown, Butterfly (Japan)

- 1988 Prize Okano (Japan)

Selected works

- "Scuole mistiche e misteriosofiche in India" [Mystical and mysteriosophical schools in India]. Asiatica (in Italian) (1): 16–21. 1936.

- "Lo spirito dell'arte orientale" [The soul of Eastern art]. Asiatica (in Italian) (2): 70–80. 1936.

- "Il paesaggio e la natura nell'arte dell'Estremo Orente" [Landscape and nature in the art of the Far East]. Asiatica (in Italian) (3): 111–117. 1936.

- "L'arte sino-siberiana" [Sino-Siberian art]. Asiatica (in Italian) (3, 1936): 140–144.

- "Spirito e forme del giardino orientale" [Spirit and shapes of the Oriental garden]. Asiatica (in Italian) (4): 181–188. 1936.

- "Cenno storico sulla pittura cinese" [Historical outline of Chinese painting]. Asiatica (in Italian) (5–6): 252–258. 1936.

- "La vita dell'antico Giappone nei diari di alcune dame di corte" [Life in Ancient Japan according to the diaries of some ladies-in-waiting]. Asiatica (in Italian) (3): 139–146. 1937.

- "Sciotoku, l'educatore dell'anima giapponese" [Shōtoku, the educator of Japanese soul]. Nuova Antologia (in Italian). fasc. 1576, year 72: 180–187. 1937.

- Giappone [Japan] (in Italian). Milan: Garzanti. 1940.

- Hideyoshi's Expansionist Policy on the Asiatic Mainland. 3rd series. Vol. III. Tokyo: Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan. 1954. pp. 74–116.

- "Hōgen monogatari, traduzione, I parte". Rivista degli Studi Orientali (in Italian). Rome. XLI, fasc. III: 207–271. 1966.

- "Hōgen monogatari, traduzione, II parte". Rivista degli Studi Orientali (in Italian). Rome. XLII, fasc. II: 121–183. 1967.

- "Hōgen monogatari, traduzione, III parte". Rivista degli Studi Orientali (in Italian). Rome. XLII, fasc. IV: 407–453. 1967.

- A Few Remarks on the Masakadoki, Chronicle of Taira no Masakado. 1973. pp. 129–133.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Stramigioli, Giuliana (1973). "Preliminary Notes on Masakadoki and the Taira no Masakado Story". Monumenta Nipponica. Tokyo. XXVIII (3): 261–293. doi:10.2307/2383784. JSTOR 2383784.

- "Masakadoki to Taira no Masakado no jojutsu ni tsuite no kenkyū josetsu" [An interpretation of the researches on the Masakadoki and on the description of Taira no Masakado]. Koten Isan (in Japanese) (26, 5): 1–30. 1975.

- "Heiji monogatari, I parte". Rivista degli Studi Orientali (in Italian). Rome. XLIX, fasc. III–IV: 287–338. 1975.

- "Heiji monogatari, II e III parte". Rivista degli Studi Orientali (in Italian). Rome. XI, fasc. II: 205–279. 1977.

- "Masakadoki ni kansuru ni san no mondai teiki" [A few questions arising about the Masakadoki]. Bungaku (in Japanese). Tokyo. 47–1: 77–84. 1979.

- "Masakadoki (traduzione)". Rivista degli Studi Orientali (in Italian). Rome. LIII, fasc. III–IV: 1–69. 1979.

- items: Giappone (letteratura), pp. 65–67; Giappone (archeologia), pp. 67–68; Kawabata, pp. 282–285; Mishima, pp. 483–484; Tange Kenzo, p. 576; Tanizaki, p. 576 in Enciclopedia Italiana (in Italian). Rome: Treccani. 1978–1981 [1961]. IV appendix.

- items: Shōmonki, Taira no Masakado, in Encyclopedia of Japan. Vol. 7. Tokyo: Kodansha. 1983. pp. 165 and 301.

References

- Burdett, Charles (2007). Journeys Through Fascism: Italian Travel-Writing between the Wars. New York; Oxford: Berghahn Books.

- Dittmer Lowell, Kim Samuel S. (1993). China's Quest for National Identity. Cornell University Press.

- Horvat, Andrew (2016). "Rashomon perceived: The challenge of forging a transnationally shared view of Kurosawa's legacy". In Davis, Blair; Anderson, Robert; Walls, Jan (eds.). Rashomon effects : Kurosawa, Rashomon and their legacies. Routledge. pp. 45–54.

- Kublin, Hyman (1959). The evolution of Japanese colonialism. Vol. II/1. Comparative Studies in Society and History. pp. 67–84.

- Kurosawa, Akira (2011). Something Like An Autobiography. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 187.

- Ciapparoni La Rocca, Teresa (2012). "Giuliana Stramigioli (1914–1988): donna, manager e docente" [Giuliana Stramigioli (1914–1988): woman, manager and teacher]. In Maurizi, Andrea; Ciapparoni La Rocca, Teresa (eds.). La figlia occidentale di Edo. Scritti in memoria di Giuliana Stramigioli [The Western daughter of Edo. Writings in memory of Giuliana Stramigioli] (in Italian). Rome: FrancoAngeli. pp. 59–72.

- Orsi, Maria Teresa (1990). "Giuliana Stramigioli (1914–1988)". Rivista degli Studi orientali (in Italian) (62–63): 143–145.

- Scalise, Mario (2003). "L'Associazione italiana per gli studi giapponesi" [The Italian Association of Japanese Studies]. In Tamburello, Adolfo (ed.). Italia Giappone – 450 anni [Italy–Japan: 450 years of history] (in Italian). Rome; Naples: Istituto italiano per l’Africa e l’Oriente–Università degli studi di Napoli «L’Orientale». pp. 697–698.

- Steenstrup, Carl (1980). "Notes on the Gunki or Military Tales: Contributions to the Study of the Impact of War on Folk Literature in Premodern Japan". Comparative Civilizations Review. 4: 1–28.