Glass float

Glass floats, glass fishing floats, or Japanese glass fishing floats are popular collectors' items. They were once used by fishermen in many parts of the world to keep their fishing nets, as well as longlines or droplines, afloat.

Large groups of fishnets strung together, sometimes 50 miles (80 km) long, were set adrift in the ocean and supported near the surface by hollow glass balls or cylinders containing air to give them buoyancy. These glass floats are no longer used by fishermen, but many of them are still afloat in the world's oceans, primarily the Pacific. They have become a popular collectors' item for beachcombers and decorators. Replicas are now manufactured.

History

Norway, around 1840, was the first country to produce and use glass fishing floats. Many of them can still be found in local boathouses. Christopher Faye, a Norwegian merchant from Bergen, is credited with their invention. The glass float was developed through cooperation with one of the owners of the Hadeland Glassverk in Norway, Chr. Berg.

The earliest mention of these "modern" glass fishing floats is in the production registry for Hadelands Glassverk in 1842. The registry shows that this was a new type of production.

The earliest evidence of glass floats being used by fishermen comes from Norway in 1844 where glass floats were on gill nets in the great cod fisheries in Lofoten. By the 1940s, glass had replaced wood or cork throughout much of Europe, Russia, North America, and Japan. Japan started using the glass floats as early as 1910. Today, most of the remaining glass floats originated in Japan because it had a large deep sea fishing industry which made extensive use of the floats; some made by Taiwan, Korea and China. In Japanese, the floats are variably known as ukidama (浮き玉, buoy balls) or bindama (ビン玉, glass balls).

Glass floats have since been replaced by aluminum, plastic, or Styrofoam.

Manufacturing

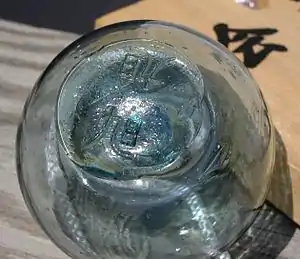

The earliest floats, including most Japanese glass fishing floats, were handmade by a glassblower. Recycled glass, especially old sake bottles in Japan, was typically used and air bubbles/imperfections in the glass are a result of the rapid recycling process. After being blown, floats were removed from the blowpipe and sealed with a 'button' of melted glass before being placed in a cooling oven. (This sealing button is sometimes mistakenly identified as a pontil mark. However, no pontil (or punty) was used in the process of blowing glass floats.) While floats were still hot and soft, marks were often embossed on or near the sealing button to identify the float for trademark. These marks sometimes included kanji symbols.

A later manufacturing method used wooden molds to speed up the float-making process. Glass floats were blown into a mold to more easily achieve a uniform size and shape. Seams on the outside of floats are a result of this process. Sometimes knife markings where the wooden molds were carved are also visible on the surface of the glass.

Dispersion

.JPG.webp)

Today most of the glass floats remaining in the ocean are stuck in a circular pattern of ocean currents in the North Pacific. Off the east coast of Taiwan, the Kuroshio Current starts as a northern branch of the western-flowing North Equatorial Current. It flows past Japan and meets the arctic waters of the Oyashio Current. At this junction, the North Pacific Current (or Drift) is formed which travels east across the Pacific before slowing down in the Gulf of Alaska. As it turns south, the California Current pushes the water into the North Equatorial Current once again, and the cycle continues. Although the number of glass floats is decreasing steadily, many floats are still drifting on these ocean currents. Occasionally storms or certain tidal conditions will break some floats from this circular pattern and bring them ashore. They most often end up on the beaches of the Western United States - especially Alaska, Washington, or Oregon - Taiwan, or Canada. However, many floats have been found on beaches and along coral reefs on Pacific islands, most notably the windward side of Guam. It is estimated that floats must be a minimum of 7–10 years old before washing up on beaches in Alaska. Most floats that wash up, however, would have been afloat for 10 years. A small number of floats are also trapped in the Arctic ice pack where there is movement over the North Pole and into the Atlantic Ocean.

Appearance

Once a float lands on a beach, it may roll in the surf and become etched by sand. Many glass floats show distinctive wear patterns from the corrosive forces of sand, sun, and salt water. When old netting breaks off of a float, its pattern often remains on the surface of the glass where the glass was protected under the netting. Other floats have small amounts of water trapped inside of them. This water apparently enters the floats through microscopic imperfections in the glass while the floats are suspended in Arctic ice or held under water by netting.

To accommodate different fishing styles and nets, the Japanese experimented with many different sizes and shapes of floats, ranging from 2 to 20 inches (510 mm) in diameter. Most were rough spheres, but some were cylindrical or "rolling pin" shaped.

Most floats are shades of green because that is the color of glass from recycled sake bottles. However, clear, amber, aquamarine, amethyst, blue and other colors were also produced. The most prized and rare color is a red or cranberry hue. These were expensive to make because gold was used to produce the color. Other brilliant tones such as emerald green, cobalt blue, purple, yellow and orange were primarily made in the 1920s and 30s. The majority of the colored floats available for sale today are replicas.

See also

Resources

- Beachcombing for Japanese Glass Floats by Amos L. Wood (Binford & Mort, 4th ed., 1985; ISBN 0-8323-0437-9)

- Glass Ball, A comprehensive Guide for Oriental Glass Fishing Floats found on Pacific Beaches by Walt Pich (First Edition 2004; ISBN 0-9657108-1-5)

- Beachcombers Guide to the Northwest, Glass Balls & Other Littoral Treasures, California to Alaska by Walt Pich (First Edition 1997; ISBN 0-9657108-0-7)

- Beachcombing the Pacific by Amos L. Wood (Schiffer, 1987; ISBN 0-88740-097-3)

- I'd Rather be Beachcombing by Bert and Margie Webber (Webb Research Group, 1991; ISBN 0-936738-20-0)