Gloster Gladiator

The Gloster Gladiator is a British biplane fighter. It was used by the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) (as the Sea Gladiator variant) and was exported to a number of other air forces during the late 1930s.

| |

|---|---|

| |

| A Gloster Gladiator in RAF markings | |

| Role | Fighter |

| National origin | United Kingdom |

| Manufacturer | Gloster Aircraft Company, Ltd. |

| Designer | Henry Phillip Folland |

| First flight | 12 September 1934 |

| Introduction | 23 February 1937 |

| Retired | 1953 (Portugal) |

| Primary users | Royal Air Force |

| Number built | 747 |

| Developed from | Gloster Gauntlet |

Developed privately as the Gloster SS.37, it was the RAF's last biplane fighter aircraft, and was rendered obsolescent by newer monoplane designs even as it was being introduced. Though often pitted against more advanced fighters during the early days of the Second World War, it acquitted itself reasonably well in combat.

The Gladiator saw action in almost all theatres during the Second World War, with a large number of air forces, some of them on the Axis side. The RAF used it in France, Norway, Greece, the defence of Malta, the Middle East, and the brief Anglo-Iraqi War (during which the Royal Iraqi Air Force was similarly equipped). Other countries deploying the Gladiator included China against Japan, beginning in 1938; Finland (along with Swedish volunteers) against the Soviet Union in the Winter War and the Continuation War; Sweden as a neutral noncombatant (although Swedish volunteers fought for Finland against USSR as stated above); and Norway, Belgium, and Greece resisting Axis invasion of their respective lands.

South African pilot Marmaduke "Pat" Pattle was the top Gladiator ace with 15 victories with the type.[1][2]

Design and development

Origins

During the 1920s, Britain's air defences had been based around interceptor aircraft capable of flying only for short ranges and at speeds of 150 to 200 miles per hour (240 to 320 km/h), but by 1930, figures within the Air Ministry were keen to supersede these aircraft. In particular, some dissatisfaction had arisen with the level of reliability experienced with the 'one pilot, two machine guns' design formula previously used; the guns were often prone to jams and being unreliable.[3] The Air Ministry's technical planning committee formulated Specification F.7/30, which sought a new aircraft capable of a maximum speed of at least 250 mph (400 km/h), an armament of no fewer than four machine guns, and such handling that that same fighter could be used by both day and night squadrons.[3] Gloster, being already engaged with development of the Gloster Gauntlet, did not initially respond to the specification, which later proved to be beneficial.[4]

The specification had also encouraged the use of the new Rolls-Royce Goshawk evaporatively cooled inline engine; many of the submissions produced by various aviation companies in response accordingly featured the Goshawk engine.[5] However, the Goshawk engine proved to be unreliable, mainly due to its overcomplex and underdeveloped cooling system, and unsuited to use on fighter aircraft and this outcome stalled development of the aircraft intended to use it.[5] A further stumbling point for many of the submitted designs was the placement of the machine gun breeches within arm's reach of the pilot. At the same time, the development of monoplane fighters such as the Hawker Hurricane and Supermarine Spitfire cast doubt over the future viability of the requirement altogether.[5]

Gloster recognised that instead of developing an all-new design from scratch, the existing Gauntlet fighter could be used as a basis for a contender to meet Specification F.7/30. Development of what would become the Gladiator began as a private venture, internally designated as the SS.37, at Gloster, by a design team headed by H.P. Folland, who soon identified various changes to increase the aircraft's suitability to conform with the demands of the specification. Making use of wing-design techniques developed by Hawker Aircraft,[6] the new fighter adopted single-bay wings in place of the two-bay wings of the Gauntlet, and two pairs of interplane struts were also dispensed with as a drag-reduction measure.[5] The Bristol Mercury M.E.30 radial engine, capable of generating 700 hp (520 kW), was selected to power the SS.37, which provided a performance boost over the preceding Gauntlet.[5] Another design choice was the fitting of a cantilever main undercarriage, which incorporated Dowty internally sprung wheel struts.[7][8]

Prototype

In spring 1934, Gloster embarked on the construction of a single SS.37 prototype.[5] On 12 September 1934, the SS.37 prototype conducted its maiden flight, piloted by Gloster chief test pilot Gerry Sayer.[5] Initially powered by a 530 hp (400 kW) Mercury IV engine, the prototype was quickly re-equipped with a more powerful 645 hp (481 kW) Mercury VIS engine. During flight tests, the prototype attained a top speed of 242 mph (389 km/h; 210 kn) while carrying the required four .303 in (7.7 mm) machine guns (two synchronised Vickers guns in the fuselage and two Lewis guns under the lower wing).[5] According to aviation author Francis K. Mason, the Air Ministry were sceptical about the aircraft achieving such performance from a radial engine design, so funded a protracted series of evaluation trials.[5]

On 3 April 1935, the prototype was transferred to the RAF, receiving the designation K5200, and commenced operational evaluations of the type.[5] Around the same time, Gloster proceeded to plan a further improved version, featuring an 840 hp (630 kW) Mercury IX engine, a two-blade wooden fixed-pitch propeller, improved wheel discs, and a fully enclosed cockpit.[9][5] K5200 was later used to trial modifications for production aircraft, such as the addition of a sliding hood for the pilot.[5]

In June 1935, production plans for the aircraft were proposed; two weeks later, a production specification, Specification F.14/35, had been rapidly drawn up, partially prompted by events in continental Europe, such as the invasion of Abyssinia by Fascist Italy and the rise of Adolf Hitler to power in Germany, in response to which the British government mandated an urgent expansion of the RAF to counter the emerging threats.[5] This culminated in an initial order for 23 aircraft. On 1 July 1935, the aircraft formally received the name Gladiator.[10][5]

Production

Manufacturing of the Gladiator was started at Gloster's Hucclecote facility. Production of the initial batch was performed simultaneously, leading to many aircraft being completed around the same time. On 16 February 1937, K6129, the first production Gladiator, was formally accepted by the RAF; on 4 March 1937, K6151, the last aircraft of the initial batch, was delivered.[5] In September 1935, a follow-up order of 180 aircraft was also received from the Air Ministry;[11] this order had the proviso that all aircraft had to be delivered before the end of 1937.[5]

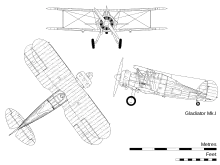

The first version, the Gladiator Mk I, was delivered from July 1936, becoming operational in January 1937. When difficulties with Rolls-Royce Merlin combustion chamber threatened to postpone the readiness of the next-generation fighters, the Air Ministry hedged its bets by procuring three hundreds of Mk II Gladiators as a stopgap via Specification F.36/37 (the delivery of 252 planes took until April 1940).[12] The main differences were a slightly more powerful Mercury VIIIAS engine with Hobson mixture control boxes and a partly automatic boost-control carburettor, driving a Fairey fixed-pitch three-blade metal propeller, instead of the two-blade wooden one of the Mark I. All MK II Gladiators also carried Browning 0.303-inch machine guns (licence-manufactured by the BSA company in Birmingham) in place of the Vickers-Lewis combination of the MK I. A modified Mk II, the Sea Gladiator, was developed for the Fleet Air Arm, with an arrestor hook, catapult attachment points, a strengthened airframe, and an underbelly fairing for a dinghy lifeboat, all for operations aboard aircraft carriers.[13][14] Of the 98 aircraft built as, or converted to, Sea Gladiators, 54 were still in service by the outbreak of the Second World War.[13]

The Gladiator was the last British biplane fighter to be manufactured, and the first to feature an enclosed cockpit. It possessed a top speed of about 257 mph (414 km/h; 223 kn), yet even as the Gladiator was introduced, it was already being eclipsed by new-generation monoplane fighters, such as the RAF Hawker Hurricane and Supermarine Spitfire, and the Luftwaffe Messerschmitt Bf 109. In total, 747 aircraft were built (483 RAF, 98 RN), with 216 being exported to 13 countries, some of which were from the total allotted to the RAF.[15][16] Gladiators were sold to Belgium, China, Egypt, Finland, Free France, Greece, Iraq, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway, Portugal, South Africa, and Sweden.

Operational history

Introduction to service

In February 1937, No. 72 Squadron, based at Tangmere, became the first squadron to be equipped with the Gladiator; No. 72 operated the type until April 1939, longer than any other home-based frontline unit.[17] Between March and April 1937, No. 3 Squadron at Kenley also received Gladiators from the remainder of the first production batch, replacing their obsolete Bristol Bulldogs.[17] Initial service with the type proved the Vickers guns to be problematical; the Gladiator was quickly armed with .303 in (7.7 mm) Browning machine guns, which were substantially more popular, leading to the other guns often only being resorted to if deemed necessary. On 27 March 1937, No. 54 Squadron at Hornchurch became the first unit to receive Browning-armed Gladiators.[17]

By September 1937, all eight Gladiator squadrons had achieved operational status and had formed the spearhead of London's air defences.[18] Difficulties with introducing the type had been experienced. Although the Gladiator was typically well-liked by pilots, the accident rate during operational training on the type was so high that a small replacement batch of 28 Gladiator Mk IIs was hurriedly produced.[17] Most accidents were caused by pilots being caught out by the fighter's increased wing loading, and many aviators had little experience in landing aircraft with such a wide flap area.[17] The aircraft had a tendency to stall more abruptly, frequently dropping a wing while doing so. The Gladiator very easily entered a flat spin, and great skill was needed to recover.[19][17]

The first use of RAF Gladiators on active service was during the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine. From September to December 1938, 33 Squadron RAF flew Gladiator strafing missions in support of British Mandate security forces. These were often in mountainous areas, and the aircraft came under substantial rifle fire. Three aircraft were destroyed, and two pilots killed, in these operations.[20]

During 1938, the RAF had begun to receive its first deliveries of the Hurricane and Spitfire monoplanes; an emphasis was soon placed on quickly re-equipping half of the Gladiator squadrons with either of these monoplane types.[21] By the outbreak of the Second World War, the Gladiator had largely been replaced by the Hurricane and Spitfire in front-line RAF service. The introduction of these aircraft had been eased by the presence of the Gladiator, squadrons that had operated Gladiators prior to converting to the monoplane types experienced a noticeably improved accident record than those who converted from older types such as the Gauntlet. Experiences such as operating the Gladiator's landing flaps and familiarisation with its sliding hood have been attributed to having favourably impacted pilot conversion.[17]

Although by 1941, all Gladiators had been withdrawn from front-line duties defending the British Isles, a need to defend Britain's trade routes throughout the overseas territories of the British Empire had been recognised, so the RAF redeployed many of its Gladiators to the Middle East to defend the theatre and the crucial Suez Canal.[21] The Gladiator saw considerable action during early stages of the war, including participating in the action in the French and Norwegian campaigns, in addition to various peripheral campaigns.[21]

China

In October 1937, the Chinese Central Government ordered 36 Gladiator Is, which were delivered in two crated batches to Guangzhou via Hong Kong. The Chinese Gladiators used the American M1919 Browning machine gun to fire American .30-06 Springfield ammunition, the main ammunition of the new Chinese Nationalist Air Force. By February 1938, these aircraft had been assembled into two squadrons and the Chinese pilots familiarised themselves with them.[22] The Gloster Gladiator had its combat début on 24 February 1938.[23] That day, in the Nanking area, Chinese-American Capt John Wong Sun-Shui (nicknamed 'Buffalo') shot down a Mitsubishi A5M "Claude" naval fighter, the first victim of a Gladiator. Wong is believed to have shot down a second A5M as the wrecks of two Japanese fighters were found.[23] During that clash, Chinese Gladiators lost two of their number.[24]

Chinese Gladiators scored several more victories over Japanese aircraft from 1938 to 1940 during the Second Sino-Japanese War. In China, Gladiators were used extensively before the start of 1940 by the 28th, 29th, and 32nd squadrons of the 3rd Group. Chinese aviators considered the Gladiator an excellent fighter in its class, but pilots soon found it increasingly difficult to hold their own against the modern A5M, and because of a lack of spare parts due to an arms embargo, the surviving Gladiators were mostly relegated to training.[25] When newer Japanese aircraft such as the Mitsubishi A6M Zero entered the theatre, the Gladiators' days were numbered. "Buffalo" Wong, the first Gladiator flying ace and first American fighter ace of the war, was eventually shot down in combat with A6M Zeros on 14 March 1941 and died two days later from his injuries.[26] Arthur Chin and he were among a group of 15 Chinese Americans who formed the original group of American volunteer combat aviators in China.[27]

The Finnish Winter War and Continuation War

During the Winter War, the Finnish Air Force (FAF) obtained 30 Mk II fighters from the UK. Ten of the aircraft were donated, while the other 20 were bought by the FAF; all were delivered between 18 January and 16 February 1940, the first entering service on 2 February 1940.[28][29] The Finnish Gladiators served until 1945, but they were outclassed by modern Soviet fighters during the Continuation War, and the aircraft was mostly used for reconnaissance from 1941. The Finnish Air Force obtained 45 aerial victories by 22 pilots with the aircraft during the Winter War and one victory during the Continuation War. Twelve Gladiators were lost in combat during the Winter War and three during the Continuation War.[28] Two pilots became aces with this aircraft: Oiva Tuominen (6.5 victories with Gladiators) and Paavo Berg (five victories).

Besides the FAF Gladiators, the Swedish Voluntary Air Force, responsible for the air defence of northernmost Finland during the later part of the Winter War, was also equipped with Gladiator fighters, known as J8s (Mk Is) and J8As (Mk IIs). The Flying Regiment F 19 arrived in Finnish Lapland on 10 January 1940 and remained there until the end of hostilities. It fielded 12 Gladiator Mk II fighters, two of which were lost during the fighting and five Hawker Hart dive bombers, plus a Raab-Katzenstein RK-26 liaison aircraft and a Junkers F.13 transport aircraft.[30] The aircraft belonged to and were crewed by the Swedish Air Force but flew with Finnish nationality markings. The Swedish Gladiators scored eight aerial victories and destroyed four aircraft on the ground. One concern was expressed when F 19's executive officer Captain Björn Bjuggren wrote in his memoirs, that the tracer rounds of the Gladiator's machine guns would not ignite the aviation spirit when penetrating the fuel tanks of Soviet bombers.

The Phoney War

At the beginning of the Second World War, during what was known as the "Phoney War", Britain deployed the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) into France to fight alongside the French army. As part of this force, RAF units operating various aircraft were dispatched to contribute, including two Gladiator squadrons.[21] Initial air operations on either side were limited by the winter weather; however, immediately following Germany's commencement of the Manstein Plan and its invasion of the Low Countries on 10 May 1940, the BEF's Gladiators participated in the Dyle Plan, an unsuccessful counterattack on German forces.[21]

From 10 May 1940 to 17 May, the Gladiators were in continuous demand on the front line, quickly losing numerous aircraft and their crews in the rapid action.[31] On 18 May 1940, a Luftwaffe bombing raid destroyed many of the BEF's Gladiators and Hurricanes on the ground at Vitry-en-Artois, shortly after which the BEF's withdrawal to Dunkirk for evacuation to mainland Britain began.[32]

Gladiators typically flew patrol flights that led to occasional clashes with Luftwaffe reconnaissance aircraft. On 17 October 1940, British Gladiators scored their first success when No 607 Squadron "B" Flight shot down a Dornier Do 18 flying boat ('8L+DK' of 2.KuFlGr 606), on the North Sea.[33] On 10 April 1941, 804 NAS took off from Hatston, in Orkney, to intercept a group of approaching German aircraft. Lt Cdr J. C. Cockburn was credited with one destroyed and Blue Section with a "damaged".[34]

The Norwegian Campaign

The Norwegian Campaign saw both Norwegian and British Gladiators battling the Luftwaffe, with the Norwegian Jagevingen fighting in the defence of Oslo on the first day of Operation Weserübung, the German invasion. Later, British Gladiators fought to provide fighter cover for the Allied reinforcements sent to the assistance of the Norwegian government.

Norwegian action

The Gladiator pilots of the Norwegian Jagevingen (fighter flight)[35] were based at Fornebu Airport. On 9 April, the first day of the invasion of Norway, the seven serviceable aircraft[36][37] managed to shoot down five German aircraft: two Messerschmitt Bf 110 fighters, two He 111 bombers and one Fallschirmjäger-laden Ju 52 transport. One Gladiator was shot down during the air battle by the future experte Helmut Lent, while two were strafed and destroyed while refuelling and rearming at Fornebu airport. The remaining four operational fighters were ordered to land wherever they could away from the base. The Gladiators landed on frozen lakes around Oslo and were abandoned by their pilots, then wrecked by souvenir-hunting civilians.[38]

No Norwegian Army Air Service aircraft were able to evacuate westwards before the 10 June surrender of the mainland Norwegian forces. Only the aircraft of the Royal Norwegian Navy Air Service (one M.F.11 and four He 115s) had the range to fly from their last bases in northern Norway to the UK. Two Army Air Service Fokker C.V.Ds and one Tiger Moth also managed to escape eastwards to Finland before the surrender. Three naval M.F.11s and one He 115 flew to Finland, landing on Lake Salmijärvi in Petsamo.[28] All the former Norwegian aircraft were later flown by the Finns against the Soviet Union.

British action

Gladiators were used also by 263 Squadron during the remaining two months of the Norwegian campaign. Prior to the German invasion of Norway, Britain had prepared this squadron with low-temperature environmental training.[32] 263 Squadron arrived on the carrier HMS Glorious on 24 April and operated from an improvised landing strip built by Norwegian volunteers on the frozen lake Lesjaskogsvatnet in Oppland in central southern Norway. On 25 April, a pair of Gladiators destroyed a Heinkel He 115 aircraft; Luftwaffe bombers attacked the runway that day, wounding several pilots on the ground.[39] By the end of the day, ten Gladiators had been destroyed for the loss of three German aircraft.[40] After less than a week, all the squadron's aircraft were unserviceable and the personnel were evacuated to Britain.[40]

Having re-equipped in Britain, 263 Squadron resumed its Gladiator operations in Norway when it returned to the north of Norway on 21 May, flying from Bardufoss airfield near Narvik. At the Narvik front, 263 Squadron was reinforced by Hurricanes of 46 Squadron, which flew to an airstrip at Skånland a few days later and several German aircraft were shot down. Due to unsuitable ground at Skånland, 46 Squadron moved to Bardufoss and was operating from this base by 27 May. The squadrons had been ordered to defend the fleet anchorage at Skånland and the Norwegian naval base at Harstad on the island of Hinnøya, as well as the Narvik area after it was recaptured. In the last days of May ground attack missions were also flown by the Gladiators against railway stations, German vehicles and coastal vessels.[40]

On 2 June, one Gladiator pilot, Louis Jacobsen, was credited with the destruction of three Heinkel He 111s, along with the probable destruction of a Junkers Ju 88 and another He 111 aircraft, during one sortie.[40] British action in the theatre was short but intense before the squadrons, due to the British government's response to the invasion of France, were instructed on 2 June to undertake Operation Alphabet the evacuation from Norway.

By then, 263 Squadron had flown 249 sorties and claimed 26 enemy aircraft destroyed. The ten surviving Gladiators landed on Glorious on 7 June.[40] Glorious sailed for home but was intercepted by the German battleships Gneisenau and Scharnhorst. Despite the valiant defence put up by the destroyers, {HMS Acasta and Ardent, she was sunk along with the aircraft from four squadrons; 263 Squadron lost its CO, S/Ldr John W. Donaldson, and F/Lt Alvin Williams along with eight other pilots.[41][42][43]

Belgium

Belgian Gladiators suffered heavy losses to the Germans in 1940, with all 15 operational aircraft lost,[44][45] while only managing to damage two German aircraft.[46] During the preceding Phoney War, on 24 April 1940 Belgian Gladiators on neutrality patrol shot down a German Heinkel He 111 bomber which subsequently crashed in the Netherlands. The bomber, V4+DA of Kampfgeschwader 1, had been damaged by French fighters at Maubeuge, France, and chased across the Belgian border.[47]

Battle of Britain

The Gloster Gladiator was in operational service with 247 Squadron, stationed at RAF Roborough, Devon during the Battle of Britain. Although no combat sorties took place at the height of the aerial battles, 247 Squadron Gladiators intercepted a Heinkel He 111 in late October 1940, without result. 239 Squadron, using Gladiators for army cooperation and 804 Naval Air Squadron, outfitted with Sea Gladiators, were also operational during the Battle of Britain.[48]

Mediterranean and Middle East theatres

In the Mediterranean Theatre during 1940–41, Gladiators saw combat with four Allied air forces: the RAF, Royal Australian Air Force, South African Air Force and Ellinikí Vasilikí Aeroporía (Royal Hellenic Air Force) squadrons. These achieved some success against the Italian Regia Aeronautica, which was mainly equipped with Fiat CR.32 and Fiat CR.42 biplanes, and against Luftwaffe bombers. The South African ace Marmaduke "Pat" Pattle (who served with the RAF), claimed 15 kills in Gladiators during the North African and Greek Campaigns, making him the highest-scoring RAF biplane ace of the war.

The 1941 Anglo-Iraqi War was unique in that the RAF and Royal Iraqi Air Force, used the Gladiator as their main fighter.[49] Gladiators also saw action against the Vichy French in Syria.[50]

Malta

A stock of 18 Sea Gladiators from 802 Naval Air Squadron had been delivered by HMS Glorious, in early 1940. Three were later shipped out to take part in the Norwegian Campaign and another three were sent to Egypt. By April, Malta was in need of fighter protection and it was decided to form a flight of Gladiators at RAF Hal Far, to be composed of RAF and FAA personnel. Several Sea Gladiators were assembled and test-flown.[51] In the siege of Malta in 1940, for ten days the fighter force defending Malta was the Hal Far Fighter Flight, giving rise to a myth that three aircraft, named Faith, Hope and Charity, formed the entire fighter cover of the island. The aircraft names came into use after the battle.[52][53][54][55] More than three aircraft were operational, though not always at the same time; others were used for spare parts.[56] No 1435 Flight, which later assumed control of Malta's air defence, took on the names Faith, Hope and Charity for its aircraft upon its reformation as the air defence unit in the Falkland Islands in 1988.

The Italian air force units deployed against Malta should have easily defeated the Gladiators but its manoeuvrability and good tactics won several engagements, often starting with a dive on Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 Sparviero bombers before the Fiat CR.42 and Macchi MC.200 escort fighters could react. On 11 June 1940, a Gladiator damaged a Macchi and on 23 June, a Gladiator flown by George Burges, managed to shoot down an MC.200.[57] Another successful pilot over Malta was "Timber" Woods who managed to shoot down two S.79s and two CR.42s, also claiming a Macchi hit on 11 June and another S.79 damaged.[58] The Gladiators forced Italian fighters to escort bombers and reconnaissance aircraft. Although the Regia Aeronautica had started with a numerical advantage and air superiority, during the summer of 1940 the situation was reversed, with Hurricanes being delivered as fast as possible and gradually taking over the island's air defence.[59]

By June, two of the Gladiators had crashed and two more were assembled.[60] Charity was shot down on 31 July 1940.[61][62] Its pilot, Flying Officer Peter Hartley, scrambled at 09.45 with fellow pilots F. F. Taylor and Flight Lieutenant "Timber" Woods, to intercept an SM.79, escorted by nine CR.42s from 23° Gruppo. During a dogfight a CR.42 flown by Serg. Manlio Tarantino shot down Hartley's Gladiator (N5519), badly burning him.[63] Woods shot down Antonio Chiodi, commander of the 75a Squadriglia five miles east of Grand Harbour. Chiodi was subsequently awarded a posthumous Medaglia d’Oro al Valor Militare, Italy's highest military award. In May 2009, the remains of Charity and others were the subject of an underwater search by NATO minesweepers.[64] Hope (N5531) was destroyed on the ground by enemy bombing in May 1941.[64] The fuselage of Faith is on display at the National War Museum, Fort St Elmo, Valletta today. The fate of at least five more Gladiators that saw action over Malta is not as well documented.

North Africa

In North Africa, Gladiators faced Italian Fiat CR.42 Falcos biplanes, which had a slightly superior performance to that of the Gladiator at higher altitudes.[65]

The first aerial combat between the biplanes took place on 14 June over Amseat. Tenente Franco Lucchini, of 90a Squadriglia, 10° Gruppo, 4° Stormo, flying a CR.42 from Tobruk, shot down a Gladiator; it was the first claim made against the RAF in the desert war.[66] On the afternoon of 24 July, CR.42s and Gladiators clashed over Bardia. A formation of 11 CR.42s from 10° Gruppo, backed by six more from the 13° Gruppo attacked a British formation of nine Blenheims that was attacking Bardia, and was in turn reportedly attacked by 15 Gladiators. The five Gladiators of 33 Squadron claimed four CR.42s destroyed.[67]

On 4 August 1940, Fiat biplanes from 160a Squadriglia of Capitano Duilio Fanali intercepted four Gladiators commanded by Marmaduke "Pat" Pattle (eventually to become one of the top-scoring Allied aces with approximately 50 claims) that were attacking Breda Ba.65s while they were strafing British armoured vehicles. The battle became confused. Initially it was thought that only the old CR.32s were involved, but there were also many CR.42s; it is likely that the then inexperienced Pattle was shot down by another future ace, Franco Lucchini. On this occasion, the Fiats managed to surprise the Gladiators, shooting down three of them.[68] Wykeham Barnes, who was shot down but survived, claimed a Breda 65, while Pattle claimed a Ba 65 and a CR.42.[69] On 8 August 1940, during another dogfight, 14 Gladiators of 80 Squadron took 16 Fiat CR.42s from 9° and 10° Gruppi of 4° Stormo (a Regia Aeronautica elite unit) by surprise over Gabr Saleh, well inside Italian territory. British pilots claimed 13 to 16 confirmed victories and one to seven probables, while losing two Gladiators.[70] Actually the Italians lost four aircraft, and four more force-landed (it seems that all were later recovered).[71] That battle highlighted the strong points of the Gladiator over the CR.42, especially the radio equipment, which had permitted a coordinated attack, being also crucial for obtaining the initial surprise, and the Gladiator's superior low-altitude overall performance, including speed and a markedly superior horizontal manoeuvrability over its Italian opponent.[71]

Overall, the few Gladiators and CR.42s clashed with a substantial parity: considering all theatres, the kill ratio was 1.2-to-1 in favour of the former, a ratio similar to that of the Bf 109 and the Spitfire in the Battle of Britain, a duel considered evenly balanced by most historians.[72] However, the Gladiator, optimised for dogfighting, met with only little success against the relatively fast Italian bombers, shooting down only a handful of them and suffering almost as many losses in the process, which could be one of the reasons for its quick retirement from first-line duty; the CR.42 on the other hand was successful against early British bombers, shooting down a hundred of them with minimal losses.[73]

Eastern Africa

In Eastern Africa, it was determined that Italian forces based on Ethiopia posed a threat to the British Aden Protectorate, thus it was decided that an offensive would be necessary, in which the Gladiator would face off against the Italian biplane fighters: Fiat CR.32s and CR.42s. On 6 November 1940, in the first hour of the British offensive against Ethiopia, the Fiat CR.42 fighters of the 412a Squadriglia led by Capt. Antonio Raffi shot down five Gloster Gladiators of 1 SAAF Sqn; among the Italian pilots was the ace Mario Visintini, who later became the top scoring pilot of all belligerent air forces in Eastern Africa (Africa Orientale) and the top biplane fighter ace of World War II. Tactically, the SAAF aircraft erred by engaging the CR.42's in a piecemeal fashion and not en masse, and they were heavily outnumbered.[74]

Early on in the offensive, Gladiators of No. 94 Squadron performed various attacks on the Italian forces; typical targets included airfields, supply depots, and aircraft. They were also assigned the mission of defending Aden airspace at day and night, and to protect Allied shipping operating in the vicinity.[75] It was in the latter role that a single 94 Squadron Gladiator, piloted by Gordon Haywood, was responsible for the surrender and capture of the Italian Archimede-class submarine Galilei Galileo.[75]

On 6 June 1941, the Regia Aeronautica had only two serviceable aircraft remaining: a CR.32 and a CR.42, therefore air superiority was finally achieved by Gladiators and the Hurricanes. The Gladiator's last air combat with an Italian fighter was on 24 October 1941, with the CR.42 of Tenente Malavolti (or, according to historian Håkan Gustavsson, sottotenente Malavolta). The Italian pilot took off to strafe British airfields at Dabat and Adi Arcai. According to the Italian historian Nico Sgarlato, the CR.42 was intercepted by three Gladiators and managed to shoot down two of them, but was then itself shot down and the pilot killed.[76] Other authors state that Malavolti managed only to fire on the two Gladiators before being shot down.[77]

According to Gustavsson, SAAF pilot (no. 47484V) Lieutenant Lancelot Charles Henry "Paddy" Hope, at Dabat airfield, scrambled to intercept the CR.42 (MM7117). Diving on it, he opened fire at 300 yards. Although the CR.42 pilot took violent evasive action, Hope pursued, closing to 20 yards and firing as it tried to dive away. There was a brief flicker of flame and the last Italian aircraft to be shot down over East Africa spun into the ground and burst into flames near Ambazzo. The next day the wreckage was found, the dead pilot still in the cockpit. Hope dropped a message on Italian positions at Ambazzo: "Tribute to the pilot of the Fiat. He was a brave man. South African Air Force." But operational record books of the Commonwealth units in the area state that they did not suffer any losses on this date. The dedication of the posthumous Medaglia d’oro al valor militare states that Malavolti shot down a Gladiator and forced another to crash land, but was himself shot down by a third Gladiator.[78] This was the last air-to-air victory in the East African campaign.[79]

Towards the end of the war Gladiators were flown by Meteorological Flight 1566 out of Hiswa, Aden.

Greece

Tension had been building between Greece and Italy since 7 April 1939, when Italian troops occupied Albania. On 28 October 1940, Italy issued an ultimatum to Greece, which was promptly rejected; a few hours later, Italian troops launched an invasion of Greece, initiating the Greco-Italian War.

Britain dispatched help to the embattled Greeks in the form of 80 Squadron, elements of which arrived at Trikkala by 19 November. That same day, the Gladiator debut came in the form of a surprise, intercepting a section of five Italian CR.42s on Coritza, only one of which returned to base. On 27 November, seven Gladiators attacked three Falcos, shooting down the lead aircraft, piloted by Com. Masfaldi, commanding the 364a Squadriglia. On 28 November, the commander of 365a Squadriglia, Com. Graffer, was shot down during a combat where seven aircraft were downed, four of them British.[80] On 3 December, the Gladiators were reinforced with elements from 112 Squadron. The following day, a clash between 20 Gladiators and ten CR.42s resulted in a loss of five, two of them Italians.[80] After a break of two weeks, 80 Sqn returned to operations on 19 December 1940. On 21 December, 20 Gladiators intercepted a force of 15 CR.42 Falcos, shooting down two with two losses.[81] Over the next few days, several groups of Italian Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 and Savoia-Marchetti SM.81 bombers were also intercepted and victories claimed.

One of the more notable Gladiator engagements of the whole war occurred on the Albanian border with Greece on 28 February 1941. A mixed force of 28 Gladiators and Hurricanes encountered roughly 50 Italian aircraft, and claimed to have shot down or severely damaged at least 27 of them.[2] A single Gladiator, piloted by ace pilot Marmaduke "Pat" Pattle, claimed five aircraft during that single skirmish.[2] Actually the British heavily overclaimed as it seems that Regia Aeronautica that day lost only two CR.42s.[71]

The complete 112 Squadron moved to Eleusis by the end of January 1941, and by the end of the following month, had received 80 Sqn's Gladiators, after the latter unit had converted to Hawker Hurricanes. On 5 April, German forces invaded Greece and quickly established air superiority. As the Allied troops retreated, Gladiators covered them, before flying to Crete during the last week of April. There No 112 Sqn recorded a few claims over twin-engined aircraft before being evacuated to Egypt during the Battle of Crete.[82]

Anglo-Iraqi War

The Royal Iraqi Air Force (RoIAF) had been trained and equipped by the British prior to independence in 1932.[83] One result of this was the dominance of British-built aircraft in the RoIAF inventory. In 1941, the sole RoIAF single-purpose fighter squadron, 4th Squadron consisted of seven operational Gloster Gladiators at Rashid Air Base.[84]

On 2 May 1941, in response to a blockade established by increasing numbers of Iraqi forces on RAF Habbaniya and demands from the revolutionary Iraqi government, a preemptive RAF attack was launched to break the encirclement. During this action, Iraqi Gladiators took part in attacks on the British air base, repeatedly strafing it ineffectively.[85] Although much of the RoIAF was destroyed in the air or on the ground in the following days, the Iraqi Gladiators kept flying until the end of the war, carrying out strafing attacks on A Company of 1 Battalion, The Essex Regiment on the outskirts of Baghdad on 30 May.[86]

Before the outbreak of hostilities in Iraq, the 4th Service Training School at RAF Habbaniya operated three old Gladiators as officers' runabouts. With the increased tension, the base was reinforced with another six Gladiators on 19 April, flying in from Egypt.[87] During the early part of the war, these nine Gladiators flew numerous sorties against air and ground targets, taking off from the base's polo field.[88] The RAF's Gladiator force in Iraq was further reinforced when, on 11 May, another five aircraft arrived, this time from 94 Squadron in Ismaïlia on the Suez Canal.[89][75] A last resupply of Gladiators came on 17 May in the form of four more 94 Squadron aircraft.[90]

During the fighting, the sole Gladiator-on-Gladiator kill occurred on 5 May, when Plt. Off. Watson of the fighter flight shot down an Iraqi Gladiator over Baqubah during a bomber escort mission. The Iraqi Gladiators' only claim during the war was a Vickers Wellington bomber shared with ground fire on 4 May.[91] RAF Gladiators proved effective against the Iraqi aircraft, which had been reinforced by Axis aircraft.[75] Immediately after launching his coup against King Faisal II in early April 1941, Prime Minister Rashid Ali al-Gaylani approached Germany and Italy for help in repelling any British countermeasures. In response, the Germans assembled a Luftwaffe task force under Iraqi colours called Fliegerführer Irak ("Flyer Command Iraq") which from 14 May operated out of Mosul.[92] Before this force collapsed due to lack of supplies, replacements, and quality fuel in addition to aggressive RAF attacks, two Gladiators fought a pair of Bf. 110s over Rashid Airfield at Baghdad on 17 May. Both German machines were swiftly shot down.[90]

The Regia Aeronautica had also dispatched a force of 12 Fiat CR.42s that arrived in Iraq on 23 May. Six days later, the Fiat CR.42s intercepted an RAF Hawker Audax and clashed with escorting Gladiators in what was to prove the final air-to-air combat of the brief campaign. Italian pilots claimed two No. 94 Sqn Gladiators; one Fiat was shot down by a Gladiator flown by Wg. Cdr. Wightman, close to Khan Nuqta.[93] Following the end of hostilities in Iraq, No 94 Squadron handed its Gladiators over to SAAF and RAAF units.[94] The Iraqis continued to operate their remaining Gladiators, some remaining in use as late as 1949;[95] these were reportedly used to conduct ground-attack missions against the Kurds.

Syria

After the end of the Iraq fighting the British invaded Vichy French-controlled Syria to prevent the area from falling under direct German control. The French in Syria had supported the Iraqi rebellion materially and allowed Luftwaffe aircraft to use their airfields for operations over Iraq. The month-long Syria-Lebanon Campaign in June–July 1941 saw heavy fighting both in the air and on land, until the Vichy French authorities in Syria surrendered on 12 July 1941. In one encounter between the Royal Air Force and the Vichy French Air Force on 15 June 1941, six Gloster Gladiators were jumped by an equal number of Dewoitine D.520 monoplane fighter aircraft. In a confused battle, both sides lost one aircraft shot down and one severely damaged. French fighter ace Pierre Le Gloan shot down the Gladiator for his 15th confirmed kill. Le Gloan himself had to crash-land his damaged D.520 at his own air base.[96]

As late as mid-1941, the RAF Chief-of-Air Staff offered 21 Gloster Gladiators gathered from various meteorological and communications flights in the Middle East, as well as five from a Free French unit, to AOC Singapore in order to strengthen the colony's defences against the emerging Japanese threat. The offer was turned down and later reinforcements consisted of Hawker Hurricanes.[97]

Operations elsewhere

The Irish Air Corps was supplied with four Gladiators on 9 March 1939. On 29 December 1940, two Irish Gladiators were scrambled from Baldonnel to intercept a German Ju 88 flying over Dublin on a photographic reconnaissance mission, but were unable to make contact.[98] Although unable to intercept any intruding aircraft, the Irish Gladiators shot down several British barrage balloons that had broken from their moorings.[99] For a short time in 1940, an order was given to Irish fighter pilots to use their aircraft to block the runways of airfields. They were then to use rifles and shoot at any invaders.[100] Irish Gladiators also overflew the site of the sinking of the liner SS Athenia in 1939 and offered the help of the Irish military. The flight was fired upon by Royal Navy ships in attendance, consequently, the Irish Gladiators withdrew.

The Luftwaffe used captured Latvian Gladiators as glider tugs with Ergänzungsgruppe (S) 1 from Langendiebach near Hanau during 1942–3.[101]

After becoming obsolete, RAF Gladiators carried out non-combat tasks such as meteorological work, being operated as such across various parts of Africa, the Middle East, and Europe as late as 1944.[102] By the end of the war, few intact aircraft remained and many of these were quickly scrapped. Two survivors were privately purchased by V.H. Bellamy, who completed a flightworthy Gladiator out of parts from L8032 and N5903, which became the sole example of the type in such a condition.[103]

Final engagements

The Finnish Air Force was the last to use the Gloster biplane in combat. It was under Finnish insignia that the Gladiator achieved its last air victory. During the Continuation War, against the Soviets, Glosters supported the advance of the Karelian Army around Lake Ladoga. On 15 February 1943, 1st Lt Håkan Strömberg of LLv 16, during a reconnaissance mission along the Murmansk railway, between the White Sea and the Lake Onega, spotted, on Karkijarvi, a Soviet Polikarpov R-5 taking off. Stromberg dived on it and shot it down into the forest near its airfield with two bursts.[104] This was the last confirmed victory in the Gladiator.

Quotations

Those old Gladiators aren't made of stressed steel like a Hurricane or a Spit. They have taut canvas wings, covered with magnificently inflammable dope, and underneath there are hundreds of small thin sticks, the kind you put under the logs for kindling, only these are drier and thinner. If a clever man said, 'I am going to build a big thing that will burn better and quicker than anything else in the world,' and if he applied himself diligently to his task, he would probably finish up by building something very like a Gladiator.

Gladiator aces

The top scoring Gladiator aces flew it in North Africa and Greece, scoring most of their successes against Regia Aeronautica aircraft. The top ace was Flight Lieutenant Pat Pattle, from No. 80 Squadron, who won 15.5 confirmed air victories while flying the Gladiator (out of his 50+ kills), plus four probably destroyed and six damaged. Second was Pilot Officer William "Cherry" Vale, from No. 33 and 80 Squadrons, with ten individual kills, 1 shared kill, and 1.5 damaged. Flight Lieutenant Joe P. Fraser, from No. 112 Squadron, and Flight Sergeant Don S. Gregory, from Nos. 33 and 80 Squadrons, scored all of their kills (respectively, 9.5 and 8) flying the Gladiator. Sergeant C. E. "Cas" Casbolt, from No. 80 Squadron, shot down 7.5 enemy aircraft (plus one probably destroyed and 1.5 damaged).[105] Rhodesian pilot Caesar Hull scored five of his eight victories in a Gladiator during the Norwegian Campaign in 1940, including four in the same afternoon. He was the leading Allied pilot of the campaign.

Top Finnish Air Force Gladiator ace was Captain Paavo Berg, who claimed 6 of his 11 victories with Gladiators. Warrant Officer Oiva Tuominen claimed 5 of his 44 victories with Gladiators. Several other FiAF aces also claimed victories with Gladiators.

Two Chinese pilots, John Wong and Arthur Chin, achieved ace status in Gladiators.[106]

Variants

- SS.37

- Prototype.

- Gladiator I

- Version powered by a single 840 hp (630 kW) Bristol Mercury IX air-cooled radial piston engine. The aircraft was designated J 8 in Swedish Air Force service. Delivered 1937–38, 378 built.

- Gladiator II

- Version powered by a single Bristol Mercury VIIIA air-cooled radial piston engine. The aircraft was designated J 8A in Swedish Air Force service. Delivered 1938–39, 270 built.

- Sea Gladiator Interim

- Single-seat fighter biplane for the Royal Navy, 38 modified Gladiator II aircraft. Fitted with arrestor hooks. Serial numbers: N2265 – N2302.

- Sea Gladiator

- Single-seat fighter biplane for the Royal Navy, 60 built. Fitted with arrestor hooks and provision for dinghy stowage. Serial numbers: N5500 – N5549 and N5565 – N5574.

Operators

.svg.png.webp) Australia

Australia.svg.png.webp) Belgium

Belgium China

China.svg.png.webp) Egypt

Egypt.svg.png.webp) Free France

Free France Finland

Finland.svg.png.webp) Germany (small numbers, including some of former Latvian and Lithuanian Gladiators)[107][108]

Germany (small numbers, including some of former Latvian and Lithuanian Gladiators)[107][108].svg.png.webp) Greece

Greece.svg.png.webp) Iraq

Iraq Ireland

Ireland Latvia – 26 units

Latvia – 26 units.svg.png.webp) Lithuania – 14 units[108]

Lithuania – 14 units[108] Norway

Norway Portugal

Portugal Romania

Romania.svg.png.webp) South Africa

South Africa.svg.png.webp) Soviet Union – took over former Latvian and Lithuanian Gladiators following the occupation of the Baltic States

Soviet Union – took over former Latvian and Lithuanian Gladiators following the occupation of the Baltic States Sweden

Sweden United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Surviving aircraft

.jpg.webp)

- Malta

- N5520 Faith – Sea Gladiator fuselage on static display at the National War Museum in Valletta.[109] It is the only surviving Gladiator from the Fighter Flight.[110] Research on the airframe has indicated that it incorporates parts of at least one other Gladiator.[111]

- Norway

- N5641 – Gladiator II on static display at the Norwegian Aviation Museum in Bodø, Nordland. It was operated by No. 263 squadron and abandoned at Lake Lesjaskog during the squadron's retreat.[112] The aircraft had been purchased by a local farmer who preserved it into the 1960s when it was brought to the museum for restoration.[113]

- Sweden

- 278 – J 8 on static display at the Swedish Air Force Museum near Linköping, Östergötland.[114]

- United Kingdom

- K8042 – Gladiator I on static display at the Royal Air Force Museum Cosford in Cosford, Shropshire.[115][116]

- L8032 – Gladiator I airworthy at the Shuttleworth Collection in Old Warden, Bedfordshire.[117]

- N5628 – Gladiator II forward fuselage on static display at the Royal Air Force Museum London in London. It is displayed unrestored.[118][119]

- N5903 – Gladiator II airworthy at The Fighter Collection in Duxford, Cambridgeshire.[120]

- N5914 – Gladiator II under restoration at the Jet Age Museum in Gloucester, Gloucestershire.[121][122][123]

- N5719 – Gladiator II Restoration at Retro Track And Air (UK) Ltd

- N5518 - Gladiator II Restoration at Fleet Air Arm Museum

Specifications (Gloster Gladiator Mk I)

Data from Gloster Aircraft since 1917,[124] The Gloster Gladiator,[125][126]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 27 ft 5 in (8.36 m)

- Wingspan: 32 ft 3 in (9.83 m)

- Height: 11 ft 9 in (3.58 m)

- Wing area: 323 sq ft (30.0 m2)

- Airfoil: RAF 28[127]

- Empty weight: 3,217 lb (1,459 kg)

- Gross weight: 4,594 lb (2,084 kg)

- Powerplant: 1 × Bristol Mercury IX 9-cylinder air-cooled radial piston engine, 830 hp (620 kW)

- Propellers: 3-bladed fixed-pitch metal propeller

Performance

- Maximum speed: 253 mph (407 km/h, 220 kn) at 14,500 ft (4,420 m)

- Cruise speed: 210 mph (340 km/h, 180 kn)

- Stall speed: 53 mph (85 km/h, 46 kn)

- Endurance: 2 hours

- Service ceiling: 32,800 ft (10,000 m)

- Rate of climb: 2,300 ft/min (12 m/s)

- Time to altitude: 10,000 ft (3,048 m) in 4 minutes 45 seconds

Armament

- Guns:

- Initially: two synchronised .303 in Vickers machine guns in fuselage sides, two .303 in Lewis machine guns; one beneath each lower wing.

- Later aircraft: four Browning .303 Mark II machine guns, two synchronised guns in fuselage sides and one beneath each lower wing.

- In at least some Sea Gladiators, provision existed for a pair of Brownings to be fitted under the upper wings as well, bringing the total to six. Official service release trials were not completed before the Sea Gladiators were replaced by later types – but some upper wing Brownings may have been fitted in the field, in particular in Malta.[128]

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

References

Citations

- Thomas 2002, p. 91.

- Mason 1966, p. 10.

- Mason 1966, p. 3.

- Mason 1966, pp. 3-4.

- Mason 1966, p. 4.

- By 1934 Hawker was parent company of Gloster

- Lumsden 1992, p.10.

- James 1971, p. 206.

- James 1971, pp. 206–207.

- Lumsden 1992, p. 12.

- James 1971, p. 207.

- "Gloster Gladiator".

- Barber 2008, p. 6

- Matricardi, Paolo. Aerei Militari: Caccie e Ricognitori. Milano: Mondadori Electa, 2006.

- Mason 1964, p. 128.

- Spencer 2003, pp. 10, 12.

- Mason 1966, p. 5.

- Mason 1966, pp. 5-6.

- Håkan & Slongo 2012.

- Thomas, A. Gloster Gladiator Aces 2002 pp.9-10 ISBN 184176289X

- Mason 1966, p. 6.

- Thomas 2006, pp. 73–75.

- Thomas 2002, p. 11.

- Thomas 2006, p. 73.

- Thomas 2002, p. 13.

- Thomas 2002, p. 12.

- Gustavsson, Håkan. "Chinese biplane fighter aces – 'Buffalo' Wong Sun-Shui" Håkans Aviation page, 2 July 2007. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- Perttula, Pentti. "Finnish Air Force Aircraft: Gloster Gladiator." Backwoods Landing Strip – Finnish Air Force Aircraft, 2007. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- Stenman and de Jong 2013, p. 52

- Henriksson, Lars. "J 8 – Gloster Gladiator (1937–1947)." Archived 12 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine Avrosys.nu, 2 January 2008. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- Mason 1966, pp. 6-7.

- Mason 1966, p. 7.

- Thomas 2002, pp. 14–15.

- Thomas 2002, p. 15.

- Crawford, Alex. "Norwegian Gloster Gladiators". webachive.org. Retrieved: 26 August 2010.

- Thomas 2002, p. 25.

- Kraglund, Ivar. "Gladiator, Gloster" (in Norwegian). Norsk krigsleksikon 1940–45. Oslo: Cappelen, 1995, p. 136. ISBN 82-02-14138-9.

- Gustavsson, Håkan. "The Gloster Gladiator in the Norwegian Army Air Service (Hærens Flygevåpen)." Håkans Aviation page, 25 May 2004. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- Mason 1966, pp. 7-8.

- Mason 1966, p. 8.

- Royal Air Force History: History of No. 263 Squadron." Archived 18 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine Royal Air Force, 22 January 2009. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- Rawlings 1969.

- "New Zealanders with the Royal Air Force (Vol. I) Chapter 3 – Meeting the German Attack." New Zealand Electronic Text Centre, University of Victoria, 2008. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- Crawford 2002, pp. 70–74.

- Spencer 2003, pp. 31–32.

- Thomas 2002, pp. 18, 94.

- Weal 2012, p. 49.

- Rimell 1990, p. 27.

- Lyman 2006, p. 27.

- Ketley 1999, p. 32

- Ministry of Information 1944, p. 8.

- Crawford 2002, pp. 120–121.

- Hayles, John. "Gladiator." aeroflight.co, 17 April 2004. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- "The fate of Gloster Gladiator 'Faith'." Archived 1 August 2015 at the Wayback Machine Malta Aviation Museum, 2009. Retrieved 12 April 2009. Archived 1 August 2015.

- Sanderson, Michael. "Faith, Hope and Charity." Archived 11 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine killifish.f9.co. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- Crawford, Alex. "Gloster Gladiators and Fiat CR.42s over Malta 1940–42. geocities.com. Retrieved: 23 October 2010.

- Gustavsson, Håkan. "Group Captain George Burges DFC OBE, RAF no. 33225." Håkans aviation page, 30 March 2009. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- Gustavsson, Håkan. "Flight Lieutenant William Joseph 'Timber' Woods DFC, RAF no. 39605 ." Håkans aviation page, 29 April 2010. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- Marcon 1997, pp. 11–15.

- Crawford 2002, pp. 59–66.

- CALL-OUT 2002 p. 32

- or on 31 July, according to the historian Håkan Gustavsson

- Shores et al. 1987, p. 41.

- "Underwater search for Gloster Gladiator 'Charity'." Archived 9 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine Malta Aviation Museum News & Events, 20 May 2009. Retrieved 10 December 2009. Archived 9 May 2012.

- Williams and Gustin 2003, p. 106.

- Jackson 1989, p. 94.

- Gustavsson, Håkan. "Biplane fighter aces: Italy, Capitano Franco Lucchini Medaglia d'Oro al Valor Militare." Håkans aviation page, 30 March 2009. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- Massimello, Giuseppe Pesce con Giovanni. Adriano Visconti Asso di guerra. Parma: Edizioni Albertelli Speciali srl, 1997.

- Thomas 2002.

- Håkan and Slongo 2010, p. 109.

- Gustavsson, Håkan. "Flight Lieutenant Marmaduke Thomas St. John Pattle, D.F.C. (39029), No. 80 Squadron." surfcity.kund.dalnet.se. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- Gustavsson and Slongo, p. 70

- Gustavsson and Slongo, p. 78

- Gustavsson, Håkan. "Biplane fighter aces, Italy, Capitano Mario Visintini." Håkans aviation page: Biplane Fighter Aces from the Second World War, 20 February 2006.

- Mason 1966, p. 9.

- Sgarlato 2005

- Emiliani et al. 1979, p. 63.

- Patri, Salvatore. L' Ultimo Sparviero dell'Impero Italiano. A.O.I. 1940–1941. Roma: IBN editore, 2006.

- Gustavsson, Håkan. "Biplane Fighter Aces from the Second World War." Håkans aviation page, 21 March 2009. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- de Marchi 1994

- Gustavsson, Håkan. "Biplane Fighter Aces: Squadron Leader William Joseph ‘Bill’ Hickey DFC, RAF no. 32035." Håkans Aviation page, 23 October 2006. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- Thomas 2002, pp. 61–69.

- Lyman 2006, p. 25.

- Lyman 2006, p. 26.

- Lyman 2006, p. 44.

- Lyman 2006, p. 84.

- Lyman 2006, pp. 16, 22.

- Lyman 2006, p. 40.

- Lyman 2006, p. 52.

- Lyman 2006, p. 68.

- Thomas 2002, p. 80.

- Lyman 2006, p. 64.

- Thomas 2002, p. 81.

- Mason 1966, pp. 9-10.

- Mason 1966, p. 12.

- Ketley 1999, pp. 31–32, 36

- Cull 2004, p. 12

- Kennedy 2008, p. 180.

- Crawford, Alex. "Irish Air Corps Gladiators." geocities.com. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- Fodor 1982, p. 134.

- Gustavsson, Håkan. "Luftwaffe use of the Gloster Gladiator during the Second World War." Håkans Aviation page. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- Gustavsson, Håkan. "Gloster Gladiator in Meteorological Flights service." Håkans Aviation page. Retrieved 11 April 2009.

- Mason 1966, p. 11.

- Thomas 2002, p. 82.

- Thomas 2002, p. 83.

- Thomas 2002, pp 12-14

- Ketley and Rolfe 1996, p. 11.

- "Gloster "Gladiator"". Plieno sparnai (in Lithuanian). Lietuvos Oreivis Nr. 4 1989 m. 1989. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- "Fort St Elmo – National War Museum". Heritage Malta. Archived from the original on 23 July 2019. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- "ROYAL AIR FORCE OPERATIONS IN MALTA, GIBRALTAR AND THE MEDITERRANEAN, 1940-1945". Imperial War Museums. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- Crawford 2002, pp. 122–123.

- "Gloster Gladiator II". Norsk Luftfartsmuseum. Archived from the original on 25 November 2018. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- Hunt, Leslie (7 December 1967). "Norwegian Gladiator Recovery". Flight International. Iliffe Transport Publications. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- "J 8". Flygvapenmuseum. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- "Gloster Gladiator 1". Royal Air Force Museum. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- Simpson, Andrew (2017). "INDIVIDUAL HISTORY [K8042]" (PDF). Royal Air Force Museum. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- "GLOSTER GLADIATOR". Shuttleworth. Archived from the original on 18 December 2018. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- "Forward fuselage of Gloster Gladiator Mk II (Salvaged remains only)". Royal Air Force Museum. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- Simpson, Andrew (2015). "INDIVIDUAL HISTORY [N5628]" (PDF). Royal Air Force Museum. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- "Gloster Gladiator G-GLAD". The Fighter Collection. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- "Gloster Gladiator N5914". Jet Age Museum. 13 July 2018. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- "Gladiator". History Journal. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- "Airframe Dossier – Gloster Gladiator II, s/n N5914 RAF, c/n Unknown". Aerial Visuals. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- James 1971, p. 226.

- Mason 1966, p. 16.

- Thetford 1957, p. 227.

- Lednicer, David. "The Incomplete Guide to Airfoil Usage". m-selig.ae.illinois.edu. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- Mason 1964, pp. 82, 117.

Bibliography

- Ministry of Information. The Air Battle of Malta, The Official Account of the RAF in Malta, June 1940 to November 1942. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1944.

- Barber, Mark. The British Fleet Air Arm in World War II. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2008. ISBN 978-1-84603-283-7.

- Belcarz, Bartłomiej and Robert Pęczkowski. Gloster Gladiator, Monografie Lotnicze 24 (in Polish). Gdańsk, Poland: AJ-Press, 1996. ISBN 83-86208-34-1.

- Bierman, John and Colin Smith. The Battle of Alamein: Turning Point, World War II. New York: Viking, 2002. ISBN 0-670-03040-6.

- Cony, Christophe (September 1998). "Les Gloster Gladiator égyptiens" [Egyptian Gloster Gladiators]. Avions: Toute l'aéronautique et son histoire (in French) (66): 39–40. ISSN 1243-8650.

- Cony, Christophe (December 1998). "Les Gloster Gladiator en Lettonie, en URSS et en Allemagne" [The Gloster Gladiator in Latvia, the USSR and Germany]. Avions: Toute l'aéronautique et son histoire (in French) (69): 21–23. ISSN 1243-8650.

- Crawford, Alex. Gloster Gladiator. Redbourn, UK: Mushroom Model Publications, 2002. ISBN 83-916327-0-9.

- Cull, Brian and Paul Sortehaug. Hurricanes over Singapore – RAF, RNZAF and NEI Fighters in Action against the Japanese over the Island and the Netherlands East Indies, 1942. London: Grub Street, 2004. ISBN 1-904010-80-6.

- Emiliani, Angelo, Giuseppe F. Ghergo and Achille Vigna. Regia Aeronautica: I Fronti Africani(in Italian). Parma: Ermanno Albertelli editore, 1979.

- Fodor, Denis J. The Neutrals (Time-Life World War II Series). Des Moines, Iowa: Time-Life Books, 1982. ISBN 0-8094-3431-8.

- Goulding, James and Robert Jones. "Gladiator, Gauntlet, Fury, Demon".Camouflage & Markings: RAF Fighter Command Northern Europe, 1936 to 1945. London: Ducimus Books, 1971.

- Green, William and Gordon Swanborough. WW2 Aircraft Fact Files: RAF Fighters, Part 1. London: Macdonald and Jane's, 1978. ISBN 0-354-01090-5.

- Gustavsson, Håkan and Ludovico Slongo. Desert Prelude: Early Clashes, June–November 1940. Hampshire UK: MMP/Stratus White Star No. 9107, 2010. ISBN 978-83-89450-52-4.

- Gustavsson, Håkan and Ludovico Slongo. Gladiator vs. CR.42 Falco 1940-41. Midland House, West Way, Botley, Oxford /New York, Osprey Publishing, 2012. ISBN 978-1-84908-708-7.

- Harrison, W.A. Gloster Gladiator in Action. Carrollton, Texas: Squadron Signal, 2003. ISBN 0-89747-450-3.

- Jackson, Robert. The Forgotten Aces: The Story of the Unsung Heroes of World War II. London: Sphere Books, 1989. ISBN 978-0-7474-0310-4.

- James, Derek N. Gloster Aircraft since 1917. London: Putnam, 1971. ISBN 0-370-00084-6.

- Kennedy, Michael. Guarding Neutral Ireland. Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2008. ISBN 978-1-84682-097-7.

- Keskinen, Kalevi and Kari Stenman. Hurricane & Gladiator (Suomen Ilmavoimien Historia 25) (bilingual Finnish/English). Espoo, Finland: Kari Stenman, 2005. ISBN 952-99432-0-2.

- Ketley, Barry, and Mark Rolfe. Luftwaffe Fledglings 1935–1945: Luftwaffe Training Units and their Aircraft. Aldershot, UK: Hikoki Publications, 1996. ISBN 978-0-951989-920.

- Ketley, Barry. French Aces of World War 2. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 1999. ISBN 978-1-85532-898-3.

- Laignelet, Gilles (November 1998). "Courrier des Lecteurs" [Readers' Letters]. Avions: Toute l'aéronautique et son histoire (in French) (80): 3. ISSN 1243-8650.

- Ledet, Michel (March 1999). "Les Gloster Gladiator norvégians" [Norwegian Gloster Gladiators]. Avions: Toute l'aéronautique et son histoire (in French) (72): 25–28. ISSN 1243-8650.

- Ledet, Michel (April 1999). "Les Gloster Gladiator portugais" [Portuguese Gloster Gladiators]. Avions: Toute l'aéronautique et son histoire (in French) (73): 38–41. ISSN 1243-8650.

- Lopez, Mario Canoniga (August–November 1990). "Fighters of the Cross of Christ". Air Enthusiast (13): 13–25. ISSN 0143-5450.

- Lumsden, Alec. "On Silver Wings – Part 19". Aeroplane Monthly, Vol. 20, No, 4, Issue 228, April 1992, pp. 8–14.ISSN 0143-7240.

- Lyman, Robert. Iraq 1941: The Battles for Basra, Habbniya, Fallujah and Baghdad. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2006. ISBN 1-84176-991-6.

- Mason, Francis K. British Fighters of World War Two, Volume One. Windsor, Berkshire, UK: Hilton Lacy Publishers Ltd., 1969. ISBN 0-85064-012-1.

- Mason, Francis K. The Gloster Gladiator. London: Macdonald, 1964.

- Mason, Francis K. The Gloster Gladiator. Leatherhead, UK: Profile Publications, 1966.

- Matricardi, Paolo . Aerei Militari: Caccia e Ricognitori (in Italian). Milan: Mondadori Electa, 2006.

- Neulen, Hans Werner. In the Skies of Europe. Ramsbury, Marlborough, UK: The Crowood Press, 2000. ISBN 1-86126-799-1.

- Patri, Salvatore.L' ultimo Sparviero dell'impero Italiano: A.O.I. 1940–1941 (in Italian). Rome: IBN editore 2006

- Pacco, John. "Gloster Gladiator Mk I" Belgisch Leger/Armee Belge: Het Militair Vliegwezen/l'Aeronautique Militare 1930–1940 (bilingual French/Dutch). Aartselaar, Belgium: J.P. Publications, 2003, pp. 56–59. ISBN 90-801136-6-2.

- Poolman, Kenneth. Faith, Hope and Charity: Three Biplanes Against an Air Force. London: William Kimber and Co. Ltd., 1954. (First pocket edition in 1958.)

- Rawlings, John D.R. Fighter Squadrons of the RAF and Their Aircraft. London: Macdonald and Jane's, 1969. (Second edition 1976.) ISBN 0-354-01028-X.

- Rimell, Ray. Battle of Britain Aircraft. Hemel Hempstead, Hertfordshire, UK: Argus Books, 1990. ISBN 1-85486-014-3.

- Sgarlato, Nico. Fiat CR.42 (in Italian). Parma: Delta Editrice, 2005.

- Shores, Christopher and Brian Cull with Nicola Malizia. Malta: The Hurricane Years. London: Grub Street, 1987. ISBN 0-948817-06-2

- Spencer, Tom. Gloster Gladiator (Warpaint Series No.37). Luton, UK: Warpaint Books, 2003. OCLC 78987788.

- Stenman, Kari (July–August 2001). "From Britain to Finland: Supplies for the Winter War". Air Enthusiast. No. 94. pp. 56–59. ISSN 0143-5450.

- Stenman, Kari and de Jong, Peter. Fokker D.XXI Aces of World War 2. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2013. ISBN 978-1-78096-062-3.

- Stulas, Saulius (January 1998). "Le chasseur biplan Gloster Gladiator, ou la fin d'une époque (5ème partie: les Gladiator Lithuaniens)" [The Biplane Fighter Gloster Gladiator, or the End of an Era (Lithuanian Gladiators)]. Avions: Toute l'aéronautique et son histoire (in French) (58): 41–43. ISSN 1243-8650.

- Thetford, Owen. Aircraft of the Royal Air Force 1918–57. London:Putnam, 1957.

- Thetford, Owen. "On Silver Wings – Part 20". Aeroplane Monthly, Vol. 20 No. 5. Issue 229, May 1992, pp. 8–15.ISSN 0143-7240.

- Thomas, Andrew. Gloster Gladiator Aces. Botley, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2002. ISBN 1-84176-289-X.

- Thomas, Andrew. "Oriental Gladiators: The combat debut for the Gloster biplane." Air Enthusiast #121, January/February 2006, pp. 73–75.

- Weal, John. He 111 Kampfgeschwader in the west. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2012. ISBN 978-1-84908-670-7.

- Williams, Anthony G. and Dr. Emmanuel Gustin. Flying Guns: World War II. Ramsbury, Marlborough, UK: The Crowood Press, 2003. ISBN 978-1-84037-227-4.

- Zbiegniewski, Andre R. 112 Sqn "Shark Squadron", 1939–1941 (bi-lingual Polish/English text). Lublin, Poland: Oficyna Wydawnicza Kagero, 2003. ISBN 83-89088-55-X.

External links

- RAF Museum

- BoB net

- Warbirds Resource Group

- Fleet Air Arm Archive

- aeroflight

- Malta Aviation Museum

- Faith, Hope & Charity

- Gladiator Camouflage and Markings Archived 14 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Håkans aviation page Biplane fighter aces

- Håkans aviation page Biplane Fighter Aces

- Håkans aviation page Biplane Fighter Aces