Goblet word

Zhīyán (卮言, literally "goblet words") is an ancient Chinese rhetorical device, supposedly named in analogy with a type of zhi wine vessel that tilts over when full and rights itself when empty. The Daoist classic Zhuangzi first recorded this term for a mystical linguistic ideology, which is generally interpreted to mean fluid language that maintains its equilibrium through shifting meanings and viewpoints, thus enabling one to spontaneously go along with all sides of an argument.

| Zhiyan Goblet words | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 巵言 | ||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 卮言 | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 치언 | ||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 卮言 | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 卮言 | ||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | しげん | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

Terminology

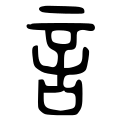

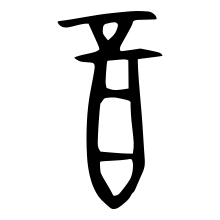

The Zhuangzi text contains neologisms for three figures of speech: yùyán (寓言, lit. "lodged words"), chóngyán (重言, "repeated words") or zhòngyán (重言, "weighted words"), and zhīyán (卮言, "goblet words")—later referred to as the sānyán (三言, "three [kinds of] words").[1] These terms compound yán (言, "speech, talk; sayings; words") with yù (寓, "lodge, reside; dwell, sojourn; entrust; imply, contain"), chóng (重, "double, multiple; duplicate, repeat; accumulate") or zhòng (重, "heavy; weight, weighty, important; serious"), and zhī (卮 or 巵, "ancient wine goblet"). All three of these ancient Zhuangzian terms became part of modern Standard Chinese vocabulary; yuyan is a common word meaning "fable; allegory; parable", chongyan is a specialized linguistic term for "reduplication, reduplicated word/morpheme", and zhiyan is a literary reference to Zhuangzi, sometimes used in self-deprecatory titles, such as Wang Shizhen's (王世貞) 1558 Yìyuan zhiyan (藝苑卮言, Goblet Words on Art and Literature).

The first Chinese dictionary of characters, Xu Shen's c. 121 CE Shuowen jiezi, provides a representative set of ancient Han dynasty "wine vessel" names. Zhī (卮 or 巵) is defined as "a round vessel (圜器), also called dàn (觛), used to regulate drinking and eating (節飲食)", which is a classical allusion to the Yijing (27). Dàn (觛) is in turn defined as a "small zhì (小觶), and the shāng (觴, "wine-drinking cup") definition says shāng refers to a full zhì (觶) and zhì to an empty one. The Shuowen defines zhì (觶) as a "ceremonial wine-drinking horn used in the countryside (鄉飲酒角)", cites the Yili "The host then sits, takes the goblet, and washes it. (一人洗舉觶)",[2] and notes that one zhi was a liquid measure equivalent to four shēng (升, about half a gallon). Zhuǎn (𦓝) is defined as a "small zhi goblet" (小巵), and shuàn (𡭐) as a "small zhi goblet with handles and a cover" (小巵有耳蓋者).

Another Han scholar Ying Shao (140-206) said zhī (卮) and zhì (觶) refer to the same object, "A regional drinking-vessel for ritual use; formerly made holding four sheng; formerly the word zhi (卮 ) was written zhi (觶) or [also pronounced di] (觝)".[3] Lin Shuen-fu disagrees with Ying and suggests zhī (卮) and zhì (觶) denote different sizes vessels of the same type and function, specifically the type of wine goblets that have a "round, column-like body, a slightly flaring mouth, and a ring foot".[4]

The historian Wang Guowei linguistically equated the zhī (卮) goblet with four ancient wine vessels: zhì (觶), dàn (觛), shuàn (𡭐), and zhuǎn (𦓝).[5] The former two are written with the standard "horn radical" (角; no. 148 in the Kangxi radicals); and the latter two with the ancient "goblet radical" (卮; no. 337 in the Shuowen Jiezi radicals), a lexicographic category with only these two rare characters.

The Chinese epigrapher Rong Geng (容庚) archaeologically concluded that the original denotations of zhì or zhī are uncertain.[6] Within the Chinese ritual bronze terminology of Song dynasty (960-1127) antiquarians, zhì (觶) was a common Western Zhou era (c. 1045-771 BCE) wine vessel with a small, oval cross section, ring-feet, slender S-shaped profile, and often a cover; and zhī (卮 or 巵) was a rare Spring and Autumn period (771-476 BCE) wine drinking vessel with a squat oval cross-section, ring-feet, and annular handles.

Chinese ritual bronze wine vessels associated with zhī (卮) goblets

Gū (觚) tall wine beaker, Shang dynasty, c. 13th century BCE

Gū (觚) tall wine beaker, Shang dynasty, c. 13th century BCE%252C_13th-11th_century_B.C.E._Bronze%252C_72.163a-b.jpg.webp) Gōng (觥) zoomorphic covered wine pitcher, Shang dynasty, c. 13th–11th century BCE

Gōng (觥) zoomorphic covered wine pitcher, Shang dynasty, c. 13th–11th century BCE Zhì (觶) wine goblet with ogre-mask motif, Western Zhou

Zhì (觶) wine goblet with ogre-mask motif, Western Zhou

Stoup is another English translation of Chinese zhī (卮 or 巵): "stoup, a cylindrical vessel reminiscent of a beer tankard or a coffee mug. It sometimes comes with a cover",[7] and "flagon, stoup, covered tankard, sometimes said to have capacity of 4 'pints' (shēng 升)".[8]

Zhuangzi

The oldest extant references to zhiyan (卮言, "goblet words") occur in chapters 27 and 33 of the c. 4th-3rd century BCE Daoist Zhuangzi. Both passages give metadiscursive analyses of the language used in Zhuangzi, namely, the sanyan three [kinds of] words, yùyán (寓言, "metaphors"), chóngyán (重言, "quotations"), and zhīyán (卮言, "impromptu words").[9] Note that unless otherwise identified, translations are by Victor H. Mair.[10]

Passages

Chapter 27 Yùyán (寓言, "Metaphors") mentions zhīyán (卮言) three times in the phrase "impromptu words pour forth every day and harmonize within the framework of nature" (Zhīyán rìchū hé yǐ tiānní 卮言日出 和以天倪), and these passages are described as "the most difficult in the entire chapter".[11] First, the lead (27/1) introduces this phrase, which two parallel passages repeat and describe how using impromptu goblet words can result in longevity. Second, the Zhuangzi (27/5) says, "Consequently, there is effusive elaboration [mànyǎn (曼衍, "spread out far and wide")] so that they may live out their years" (卮言日出 和以天倪 因以曼衍 所以窮年). Third, the context (27/9) asks a fēi (非, "not") negative conditional question, "If it were not for the impromptu words that pour forth every day and harmonize within the framework of nature, who could last long?" (非卮言日出 和以天倪 孰得其久).

Metaphors are effective nine times out of ten and quotations seven times out of ten, but impromptu words come forth every day and harmonize within the framework of nature [卮言日出 和以天倪].

Metaphors are effective nine times out of ten because they borrow externals to discuss something. A father does not act as a matchmaker for his son. It's better for someone who is not the father to praise the son than for the father himself to do so. Then it won't be his own fault, but somebody else's fault. If someone agrees with oneself, one responds favorably, but if someone does not agree with oneself, one opposes them. One considers to be right those who agree with oneself and considers to be wrong those who disagree with oneself

Quotations are effective seven times out of ten because their purpose is to stop speech. They are from our elders, those who precede us in years. But those who fill up the years of their old age without grasping what is significant and what is rudimentary are not really our predecessors. If a man has not that whereby he precedes others, he lacks the way of humanity. If a man lacks the way of humanity, he may be called a stale person.

Impromptu words pour forth every day and harmonize within the framework of nature [卮言日出 和以天倪]. Consequently, there is effusive elaboration so that they may live out their years [因以曼衍 所以窮年]. Without speech, there is equality. Equality plus speech yields inequality; speech plus equality yields inequality. Therefore, it is said, "Speak nonspeech." If you speak nonspeech, you may speak till the end of your life without ever having spoken. If till the end of your life you do not speak, you will never have failed to speak. There are grounds for affirmation and there are grounds for denial. There are grounds for saying that something is so and there are grounds for saying that something is not so. Why are things so? They are so because we declare them to be so. Why are things not so? They are not so because we declare that to be not so. Wherein lies affirmation? Affirmation lies in our affirming. Wherein lies denial? Denial lies in our denying. All things are possessed of that which we may say is so; all things are possessed of that which we may affirm. There is no thing that is not so; there is no thing that is not affirmable. If it were not for the impromptu words that pour forth every day and harmonize within the framework of nature, who could last long [非卮言日出 和以天倪 孰得其久]?

The myriad things are all from seeds, and they succeed each other because of their different forms [萬物皆種也 以不同形相禪]. From start to finish it is like a circle whose seam is not to be found [始卒若環 莫得其倫]. This is called the celestial potter's wheel, and the celestial potter's wheel is the framework of nature [是謂天均 天均者 天倪也] (27/1-10).[12]

The last part of this passage (27/10) equates tiānní (天倪, tr. "framework of nature") with the word tiānjūn (天均, "celestial potter's wheel") that occurs in two other Zhuangzi contexts. These interchangeable phonetic loan characters are jūn (均, "well balanced; equal; even; uniform; potter's wheel") and jūn (鈞, "potter's wheel; ancient unit of weight [approx. 15 kilos]; balance, harmonize") are graphically differentiated by the "earth" and "metal" radicals. The former context says, "the sage harmonizes the right and wrong of things and rests at the center of the celestial potter's wheel", and the latter, "Knowledge that stops at what it cannot know is the ultimate. If someone does not subscribe to this, he will be worn down by the celestial potter's wheel" (2/40 and 23/45).[13]

The final Zhuangzi chapter 33 Tiānxià (天下, "[All] Under Heaven"), which summarizes early Chinese philosophy, reiterates and rearranges yuyan "lodged words," chongyan "repeated words," and zhiyan "goblet words" in a context describing Zhuangzi's delight upon hearing ancient Daoist teachings. Like the goblet, this passage inverts the hierarchy of the three categories first presented in Chapter 27, and rights it by emphasizing zhiyan as the most important and inclusive type of words.[14]

With absurd expressions, extravagant words, and unbounded phrases [以謬悠之說 荒唐之言 無端崖之辭], he often gave rein to his whims but was not presumptuous and did not look at things from one angle only. Believing that all under heaven were sunk in stupidity and could not be talked to seriously, he used impromptu words for his effusive elaboration, quotations for the truth, and metaphors for breadth [以巵言為曼衍 以重言為真 以寓言為廣]. Alone, he came and went with the essential spirits of heaven and earth but was not arrogant toward the myriad things (33/64-6).[15]

This word mànyǎn (曼衍, tr. "effusive elaboration") was also used with "goblet words" above (27/5), "Consequently, there is effusive elaboration so that they may live out their years"

Commentaries

Chinese scholarly commentaries on the Zhuangzi, dating back to Guo Xiang (252-312 CE), the earliest redactor and editor of the text, provide invaluable information on understanding zhīyán (卮言, "goblet words"). For semantic perspective, summaries of how major commentators explain the related terms yùyán (寓言, "lodged words") and zhòngyán (重言, "weighted words") or chóngyán (重言, "repeated words") will be presented first. Most Zhuangzi commentaries agree that zhiyan are divided into yuyan and zhongyan subcategories, which are overlapping as the percentages require.[16]

Yùyán. Guo Xiang notes that yù (寓, "lodge; reside; relocate") means jì (寄, "lodge at temporarily; stop over; entrust to; confide in") [the words of] another person (寄之他人). Lu Deming's c. 583 exegetical Jingdian Shiwen (Textual Explanations of Classics and Canons) glosses yù as tuō (託, "entrust to; confide to; commit to the care of; rely on"). The subcommentary by Daoist Chongxuan School master Cheng Xuanying (fl. 631-655) explains that although common people are stupid, unreasonable, and suspicious of Daoist teachings (世人愚迷妄為猜忌聞道己說則起嫌疑), using yùyán to lodge in their viewpoints will enable them to understand, as exemplified by Zhuangzi's famous allegorical characters such as Hong Meng (Vast Obscurity) and Yun Jiang (Cloud General).

Zhòngyán (重言, "weighted/weighty words) or chóngyán (重言, "repeated words") are two main alternate readings. Guo Xiang implied that the Zhuangzi term should be read zhongyan, "the weighty authorities of the time" (世之所重) the commentary of Guo Qingfan (郭慶藩, 1844-1896) cites his father Guo Songtao (1818-1891) that it should be read chongyan, meaning "repetitions of words".[17] Cheng's subcommentary says it refers to ancient sayings of respected (zūnzhòng 尊重) local elders, personages such as the Yellow Emperor and Confucius.

Zhiyan (卮言, "goblet words") occur three times in chapter 27. For the first statement (27/1) that "impromptu words pour forth every day and harmonize within the framework of nature", Guo Xiang explains how "goblet words" suí (隨, "follow after; pursue; go along with; naturally adjust to") the changing meanings of their referents like a self-righting zhi goblet.

A goblet when full gets tipped and when empty is set upright [夫巵 滿則傾 空則仰]—it does not just stay the same. How much the more this is true of words, for they change [隨] according to what they refer to. Since they but follow them (their referents), this is why the text says they "appear day by day" [rìchū 日出, "sunrise"]. "Appear day by day" means "new each day" [rìxīn 日新, "daily renewal"]. Since they are new each day, they fulfill what is naturally allotted to them [zìrán zhī fēn 自然之分, "natural boundaries"], and because their natural allotments are thus fulfilled, they operate harmoniously.[18]

Cheng Xuanying notes a zhi goblet is a "wine vessel" (酒器), and glosses zhiyan as words spoken wuxin (無心, lit. "not heart-mind", "unwittingly; unintentionally; unconsciously") that go along with either side of an argument.

A goblet when full gets tipped and when empty is set upright [夫巵 滿則傾 巵空則仰]. Whether it is tipped or set upright depends on [隨] someone. Words uttered unconsciously [無心之言], this is what "goblet words" are. Therefore, one either does not speak or one's speech is done without any "tipping" or "being set upright." Only then do words match what is naturally allotted to them.[18]

Cheng cites the alternate interpretation of Guo's contemporary Sima Biao (c. 238-306) that the text used zhī (卮, "goblet") as a pun on the phonetic loan character zhī (支, "divergent; different") in zhīlí (支離, "fragmented; disorganized; jumbled"), taking zhiyan (卮言) to mean "words that are irregular, uneven, and jumbled, having neither a head nor a tail".[4]

For the second occurrence of "goblet words" in the statement that "Consequently, there is effusive elaboration so that they may live out their years" (27/5), Guo's commentary says that since "natural boundaries" (自然之分) are dominated by neither right nor wrong and "effusively elaborate" (曼衍), no one can determine which is right. Thus, one can be in a worry-free state of mind and live out one's natural lifespan. Cheng Xuanying defines mànyǎn (曼衍, tr. "effusive elaboration") as wuxin (無心, "unconsciously; unintentionally"), which he uses above (27/1) to define zhiyan, and explains that by following (隨) the changes of each new day and harmonizing with natural boundaries, one can abide with the universal and instinctively deal with everything.

Third, Zhuangzi (27/9) rhetorically questions "If it were not for the impromptu words that pour forth every day and harmonize within the framework of nature, who could last long?" Guo Xiang points out that we can avoid problems if our words follow (隨) the zhì (制, "cut; design") of things and conform to (天然之分) "natural boundaries", replacing his above zìrán (自然, lit. "self-so", "nature; natural") with the near-synonym tiānrán (天然, lit. "heaven-so", "natural, not artificial; innate"). Cheng's subcommentary says the only way to achieve Daoist longevity is by following (sui 隨) daily changes and having regard for natural principles.

Guo does not comment on chapter 33's "he used impromptu words for his effusive elaboration, quotations for the truth, and metaphors for breadth". However, Cheng glosses zhiyan goblet words as bùdìng (不定, "not sure; uncertain; indefinite") and repeats his (27/5) gloss of mànyǎn (曼衍) as wúxīn (無心, "unconsciously"), which differs from his (27/1) gloss of zhiyan as wúxīn zhī yán (無心之言, "words uttered unconsciously").

Translations

Describing the crosslinguistic difficulties of deciphering the Zhuangzi, the translator A. C. Graham said it perfectly illustrates "the kind of battering which a text may suffer between being written in one language and being transferred to another at the other end of the world some two thousand years later".[19] Translating the Old Chinese word zhiyan (卮言, lit. "goblet word/saying") into English exemplifies these problems.

Compare how some notable translations of the Zhuangzi render the sanyan (三言) contexts. In cases where translations have internal inconsistencies, the most common one is cited; take Legge for instance, "words are like the water that daily fills the cup", "Words like the water that daily issues from the cup", "words of the (water-)cup", " and "words of the cup".[20]

| Translation | Yuyan (寓言) | C-/Z-hongyan (重言) | Zhiyan (卮言) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Balfour[21] | metaphors | quotations | words which shape themselves according to surrounding circumstances |

| Legge[22] | metaphorical language | illustrations taken from valued writers | words of the (water-)cup |

| Giles[23] | language put into other people's mouths | language based upon weighty authority | language which that flows constantly over, as from a full goblet |

| Ware[24] | parables | quotations | imprecise talk |

| Watson[25] | imputed words | repeated words | goblet words |

| Graham[26] | saying from a lodging-place | "weighty" saying | "spillover" saying |

| Mair[10] | metaphors | quotations | impromptu words |

| Ziporyn[27] | words ... presented as coming from the mouths of other people | citations from weighty ancient authorities | spillover-goblet words |

Yuyan (寓言) is commonly translated[28] in the modern Chinese meaning of "metaphor". Watson explains his "imputed" translation to mean "words put into the mouth of historical or fictional persons to make them more compelling",[29] which Ziporyn adapts. Following Guo Xiang's commentary that yù (寓, "lodge") means jì (寄, "lodge temporarily; impart" metaphorical meaning), Graham translates yuyan as "saying from a lodging-place", meaning the "temporary standpoints between which the sage circulates as the situation changes", and concludes, "the lodging-place is the standpoint of the other party in the debate. Although nothing can be settled by disputation, in which everyone has started from his own choice of names, it is possible to convince a man by temporarily assuming his standpoint and arguing from it".[30]

The present sample of Zhuangzi translators are divided between parsing as chóngyán (重言, "repeated words") or zhòngyán (重言, "weighty/weighted words). The former is evident in "quotations",[31] "illustrations taken from valued writers",[22] and literally translated "repeated words", Watson, who notes "words of the wise old men of the past which are 'repeated' or quoted to give authority to the argument".[29] The latter interpretation appears in "language based upon weighty authority",[23] and "'weighty' saying", Graham remarking that "Weighted saying is the aphorism with the weight of the speaker's experience behind it."[32] Ziporyn's "citations from weighty ancient authorities" translation splits the difference. "Opalescent words" is an alternative translation of chongyan, which are "'double-rayed', that is, they say something to obey the authority of what they do not say, being 'opalescent' to the light of actuality".[33]

Several authors explain their translations of the semantically obscure word zhiyan (卮言). Giles notes that it refers to the "natural overflowings of the heart.".[34] Burton Watson says that "goblet words" are words that "adapt to and follow along with the fluctuating nature of the world and thus achieve a state of harmony".[29] Graham gives two explanations of "'spillover' sayings".

We are told that it is for daily use, says most when it says least and least when it says most, that it shifts freely from one standpoint to another, and that we cannot prolong discourse or live out our lives without it. Presumably this is the ordinary language in which meanings fluctuate but right themselves in the spontaneous flow in discourse, providing that the speaker has the knack of using words, can 'smooth it out on the whetstone of Heaven.'[35]

And it is "speech characterised by the intelligent spontaneity of Taoist behaviour in general, a fluid language which keeps its equilibrium through changing meanings and viewpoints".[30] Watson says "goblet words" "adapt to and follow along with the fluctuating nature of the world and thus achieve a state of harmony".[29] Acknowledging the "enormous variety of speculative opinion" about the meaning of zhiyan "goblet words", Mair suggests it is "language that pours forth unconsciously and unpremeditatedly".[36]

The Zhuangzi commentary of Wang Xianqian (王先謙, 1842-1917) says liquids adjust to a goblet's shape like goblet words follow individual semantics, and advises us to think flexibly and agree with the inconsistencies of what people say.

Zhang Mosheng (張默生, 1895-1979) described zhiyan as language without any fixed opinion, like a lòudǒu (漏斗, "funnel") simply channeling the sound; "The zhi is a funnel, and zhiyan is funnel-like language. A funnel is hollow and bottomless, so that if one pours in water, it immediately leaks out.".[37]

Modern interpretations

Numerous academics, described as "phalanxes of scholars",[38] have analyzed and explained zhiyan "goblet words". A survey of recent Chinese-language scholarship about zhiyan variously explain it as allegorical dialogue, toast-like salutations to Zhuangzi readers, words as endless as a circle, a hypernym of yuyan and chongyan, and comparable to fu poetry.[39] As seen below, English-language studies of Zhuangzian goblet words are also wide-ranging, for instance comparing them with the writings of Euripides,[40] Plato,[41] and Kierkegaard.[42]

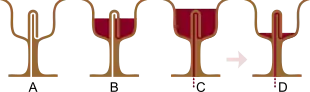

The sinologist and translator D. C. Lau proposed that Guo Xiang's commentary referred to the rare Chinese qīqì (欹器, "tilting vessel"), which is known in the Daoist tradition as yòuzhī (宥卮, "a cup for urging wine on a guest", or "warning goblet")[43] and in the Confucian tradition as yòuzuò zhī qì (宥座之器, "a cautionary vessel placed beside one's seat on the right"). In the Daoist version illustrating the value of emptiness (e.g., Huainanzi), the vessel is upright when empty and overturns when full. By contrast, in the Confucian version illustrating the value of the mean (e.g., Xunzi), the vessel tilts to one side when empty, remains upright when filled to the middle, and overturns when filled to the brim.[44]

John Allen Tucker, professor of East Asian history at East Carolina University, says the zhi goblet, which repeatedly fills and empties itself, does not remain in any particular condition, its equilibrium exists in disequilibrium, and zhiyan "goblet words" are a metaphor for the dialectic in the Zhuangzi that goes from one possibility to the next, assuming perspectives often in order to ridicule them, but never clinging to any position itself. This particular goblet is also a Zhuangzian metaphor that expresses the semantic relationship between words and their meanings. "The goblet is like a word, the meaning is like the wine. Though the goblet can hold wine, and a word, meaning, this kind of goblet continuously spills its wine, just as words spill their meaning, and then both wait for another use. But like the goblet, there is no particular meaning which is statically filling the word, never being emptied or renewed.".[45]

The University of Michigan professor of Chinese literature Shuen-fu Lin correlates zhi, the empty goblet that does not hold onto anything, with xin "heart-mind" and explains how zhiyan "goblet words" can adapt the meaning of any term:

[T]he zhi—a wine vessel used as a metaphor for the mind [xin]—is originally empty and gets temporarily filled with liquid—a metaphor for words—which comes from a larger wine container only when the occasion requires one to do so.... Since the mind is like the zhi vessel without any fixed or constant rules or values of its own stored in there, and takes ideas always from outside when the occasion for speech arises, it will never impose artificial distinctions and discriminations upon things. This is what [is meant by] "mindless"—the "mind" to be done away with here is, of course, the chengxin or "fully formed heart/mind" ... Zhiyan [spillover sayings], then, is speech that is natural, unpremeditated, free from preconceived values, always responding to the changing situations in the flow of discourse, and always returning the mind to its original state of emptiness as soon as a speech act is completed.[46]

Lee H. Yearly, a Stanford University professor of religious studies, extends the Zhuangzian sanyan "three kinds of language" to a basic issue in religious ethics, how to persuasively represent a transcendent world central to our fulfillment that exceeds our normal understanding. Zhiyan "goblet or spillover language" is described as "that kind of fluid language in which equilibrium is kept despite (or perhaps because of) the presence of changing genres, rhetorical forms, points of view, and figurative expressions".[47] Yearly traces out ways in which Zhuangzi's three kinds of language appear in Dante's 1320 Divine Comedy to illustrate universals of presentation and persuasion in religious ethics texts. Exemplifying goblet language in the Inferno, Dante presents "dazzling shifts in locale, perspective, and even physical structure", as in the case of Pietro della Vigna's appearance as a bush, or Vanni Fucci's metamorphoses into a snake.[48]

Kim-Chong Chong, professor of comparative philosophy at Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, says the paradoxical nature of "goblet words" teaches one to "be open to multivalence, and not attached to specific views", and explains this in terms of Donald Davidson's (1978) philosophical hypothesis that a metaphor has no cognitive content beyond its literal meaning, and thus Zhuangzi is able to "stay free of (being attached to) any distinctions".[49]

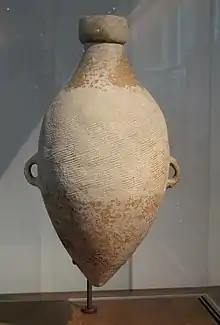

Daniel Fried, professor of Chinese and comparative literature at the University of Alberta, combined Chinese textual and archeological evidence to propose a "speculative history" of the Zhuangzian zhīyán "goblet words" trope as a reference to an ancient irrigation device known as the qīqí (欹器, "tipping vessel", cf. Lau above), which tipped and spilled its contents once it reached capacity. In the 1950s, Chinese archeologists excavating the Banpo site in Shaanxi discovered narrow-mouthed, narrow-bottomed amphora jugs dating from Neolithic Yangshao culture (c. 5000-c. 4000 BCE). One researcher[50] first identified this particular shape of narrow-bottomed jug as the referent in both the Xunzi passage on the qiqi, and the Guo Xiang commentary on the zhi. The use of the vessel in irrigation "was driven by its ability to deliver a constant, low-flow stream of water, without the attention of the farmer, who held strings attached to the handles while the jugs tipped over of themselves".[51] Fried's agricultural reading of zhiyan as meaning "tipping-vessel words" instead of "goblet words" explains several hermeneutical problems with the Zhuangzi context. For instance, the word mànyǎn (曼衍, "spread out far and wide") is inappropriate to the goblet metaphor, and would be an "awful mess if meant to describe alcohol".[52] It is figuratively translated as "effusive elaboration" in the sentence "Consequently, there is effusive elaboration so that they may live out their years [因以曼衍 所以窮年]". However, if zhi refers to a tipping-vessel anciently used for irrigation, then manyan is a natural extension of the basic metaphor. "Spreading out" water over an entire field is simply the definition of irrigation.[53] Fried asks what Zhuangzian zhi words could be irrigating and answers zhǒng (種, "seeds"). "The myriad things are all from seeds, and they succeed each other because of their different forms [萬物皆種也 以不同形相禪]." This abstruse metaphor of all objects as seeds makes little sense in the context of wine goblets, but it is "entirely sensible if one has been speaking of agriculture from the beginning". A final example is that Confucius' disciples fill the vessel with water, not wine.[54]

The religious studies scholar Jennifer R. Rapp identifies the sanyan "three kinds of language" in the Zhuangzi as a "chorus-like" discursive strategy comparable with the Greek chorus in Euripides' The Bacchae. "Goblet language", for instance, deflects attention from the exemplar sage figure Zhuang Zhou, while also "dissolving the static notion of authorial position or authority", which Wang calls the "structural disappearance of the author the shift and multiplying of meanings and viewpoints".[55] In the Bacchae, the chorus is certainly in the shadow of the authority Dionysus, which creates a third voice in relation to the audience, allowing them to enter the world of the play.[56]

Youru Wang, professor of Religion Studies at Rowan University, describes zhiyan "goblet words", "They adapt to and follow along with changes in things and people. They are not fixed signifiers or signifieds. Therefore, though they seem outlandish or absurd, deviating from common sense or formal logic, they are in harmony with what is natural (what is spontaneously so), with the flux of all things and circumstances."[57] "Goblet communication" is a type of indirect communication (a central theme in Søren Kierkegaard's Practice in Christianity), broadly defined as "listener- or reader-oriented, and non-teleological; it assumes an interactive relation between the speaker and the listener; it abandons the correspondence theory of language; it is concerned with the existentio-practical dimension of what is communicated; it considers meaning open-ended and indeterminate"; indirect communication particularly adopts indirect language, such as metaphor, denegation, paradox, and irony.[58]

E. N. Anderson, professor of anthropology at University of California, Riverside, proposes that the unstable zhi was originally some kind of drinking horn or rhyton designed to tip over when set down, so that anyone who drinks from one must empty it.[59] The jiǎo (角) "horn radical" semantic indicator in zhì (觶) and dàn (觛) above is a recurring element in ancient Chinese wine vessel names, such as the gōng (觥, "zoomorphic covered wine pitcher"). Besides this character's usual jiǎo "horn" reading, it was also pronounced jué (角) as the name of an ancient wine vessel similar to a jué (爵), except the spout and brim extension are identical and there is a cover.

The University of Delaware professor of Asian and comparative philosophy Alan Fox says the willingness to surrender one's own perspective to the perspective of another person is "a prerequisite to effective communication", and quotes the final passage in Zhuangzi chapter 26, "A fish-trap is for catching fish; once you've caught the fish, you can forget about the trap. .... Words are for catching ideas; once you've caught the idea, you can forget about the words. Where can I find a person who knows how to forget about words so that I can have a few words with him?".[60]

To forget words is to surrender allegiance to one's own perspectives and sense of meaning. This is difficult because we tend to identify strongly with our familiar perspectives. We take them personally. Forgetting words involves really listening to the other. A person capable of this is a desirable partner for conversation, because he or she has no preferences at stake and will not insist on projecting any inappropriate meanings onto our statements—unlike most people who seem all too eager to misinterpret each other. A person who has forgotten words will come to terms with us, understand us as we understand ourselves by using language without being hampered by or fixated on any favorite or popular sage. This flexibility limits misunderstanding and, since clarity is a privileged cognitive mode, is thus of value.[61]

Fox describes zhiyan (卮言, "goblet words"), which Mathews' Chinese–English Dictionary translates as "all-embracing expressions, words which flow from the heart like water overflowing from a goblet" (930), to be the "most sophisticated use of language" in the Zhuangzi. Chapter 27 recommends to, "Speak nonspeech." If you speak nonspeech, you may speak till the end of your life without ever having spoken. If till the end of your life you do not speak, you will never have failed to speak.".[62] Accordingly, "This kind of mercurial or fluid language use empties itself of meaning in order to refill itself; it adapts to, and follows along with, the fluctuating nature of the world, communicating meaning in any given circumstance more accurately and appropriately".[63]

The Lingnan University philosophy professor Wai-wai Chiu analyzes three logical forms of Zhuangzian "goblet words", all of which serve to preserve indeterminacy and prevent reaching a definitive answer to any conceptual disputation. First, dilemmatic questions in the Zhuangzi are typically "Is X acceptable? Or is not-X acceptable?", where the excluded middle suggests that we can accept either one, but not both.[64] For example, "Speech is not merely the blowing of air. Speech is intended to say something, but what is spoken may not necessarily be valid. If it is not valid, has anything actually been spoken? Or has speech never actually occurred? We may consider speech to be distinct from the chirps of hatchlings, but is there really any difference between them?".[65] Second, oxymorons combining contradictory terms are common in the text.[66] For instance, "The great Way is ineffable, great disputation is speechless, great humaneness is inhumane, great honesty is immodest, and great bravery is not aggressive.".[67] Third, "double denial" is a type of goblet word that doubts or criticizes a view and then immediately doubts its original doubt, and which, unlike an oxymoron, can have a consistent literal reading.[68] Master Tall Tree tells Master Timid Magpie, "Someone who dreams of drinking wine at a cheerful banquet may wake up crying the next morning. Someone who dreams of crying may go off the next morning to enjoy the sport of the hunt. When we are in the midst of a dream, we do not know it's a dream. Sometimes we may even try to interpret our dreams while we are dreaming, but then we awake and realize it was a dream. Only after one is greatly awakened does one realize that it was all a great dream, while the fool thinks that he is awake and presumptuously aware.".[69] The Zhuangzi employs goblet words to display various theses without arriving at a definite conclusion. Chiu discusses the effects of reading Zhuangzian goblet words. Readers may become more open-minded by "reflecting on all sides of any distinction made in the text and through their awareness of the absence of an ultimate answer".[70]

University of Hawaii at Manoa researcher Jeremy Griffith compares Zhuangzian zhiyan "spillover-goblet words" with Plato's image of "leaky-pots" symbolizing the impossibility of language in a state of flux. In the Cratylus, Plato rejects the Heraclitean hypothesis that the world is in ever-present change. "[S]urely no man of sense can put himself and his soul under the control of names, and trust in names and their makers to the point of affirming that he knows anything; nor will he condemn himself and all things and say that there is no health in them, but that all things are flowing like leaky pots, or believe that all things are just like people afflicted with catarrh, flowing and running all the time" (440).[71] Griffith describes a zhi spillover-goblet as a vessel hinged below its center of gravity, and as the vessel fills, its center of gravity raises above the level of the hinge, and it tips over, spilling its contents, only to right itself to be filled again. "In contrast with the image of the 'leaky pot,' forever losing its meaning, we have now the 'spillover-goblet,' emptying itself purposely so that it may always be refilled.".[72]

Wim De Reu, National Taiwan University philosophy professor, argues against the general academic consensus that zhiyan are a Zhuangzian literary stylistic form and suggests instead they are definite yet provisional everyday speech acts that enable one to avoid or dissolve conflicts, thus reducing the risk of untimely death. Recent studies on zhiyan tend to converge on three points. First, the notion refers to a Zhuangzian philosophical style that includes the use of paradox, denegation, dilemmatic questions, genre mixing, and seemingly unconnected passages.[73] Second, zhiyan are characterized by instability or indeterminacy.[74] And third, they create an openness that potentially transforms the reader's personality as well as his or her understanding of the world.[75] The author says it is unfortunate that recent literature on "goblet words" has not given much attention to qiongnian (窮年, "to live out your years") because it is identified as the main function of zhiyan.[76] Chapter 27 describes zhiyan with the phrases qióngnián (窮年, tr. "live out their years") in "Impromptu words pour forth every day and harmonize within the framework of nature. Consequently, there is effusive elaboration so that they may live out their years."; and dé qí jiǔ (得其久, "last long") in "If it were not for the impromptu words that pour forth every day and harmonize within the framework of nature, who could last long?".[62] De Reu prototypically describes "goblet words":

Zhiyan are simple-form verbal utterances located on the level of everyday human interaction (what they are); by virtue of being both provisional and definite, they adapt to the unambiguous position of an opponent in a dispute (how they work); by thus removing the source of conflict, they reduce the risk of untimely death and allow the language user to complete his natural life span in peaceful coexistence with others (the function they perform).[77]

Christopher C. Kirby, professor of philosophy at Eastern Washington University, interprets zhiyan goblet words in terms of non-cognitive moral realism, a conception of truth largely unfamiliar to Western philosophical traditions, and introduces the phrase "tipping toward the truth" to characterize its distinctively metaphorical moral discourse.[78] Textual passages suggest Zhuangzi believed that moral reals (i.e., attitude-independent norms) exist, but they are propositionally ineffable in a dynamic world. He employed "intentionally open-ended" goblet words as signposts pointing to the moral lessons he sought to convey, despite the factual inaccuracies of the words themselves. "These 'truths', which Zhuangzi's goblet words 'tip toward', might be accessed non-cognitively through attuning with the natural world, listening to one's body, and refining technical skill. The goal of these practices is the transformation of the self in harmony with the constant changes of nature – an emergent 'bringing forth' of normativity that cannot be put into words".[79] Following the construal of Fried,[80] Kirby says the zhīyán name refers to the ancient qīqí (欹器) irrigation vessel, which tipped and spilled its contents once it reached capacity. Zhuangzian goblet words are drained of their content once their usefulness has been exceeded, like the ancient Pythagorean cup, a practical-joke goblet, which when filled beyond a certain point, siphons its entire contents through the base.[81]

See also

- Dribble glass, a prank drinking glass with hidden holes that spill the drink when tilted

- Fuddling cup, a three-dimensional puzzle drinking vessel made of multiple cups linked together by holes and tubes, making it difficult to drink from without spilling

- Puzzle jug, a practical-joke vessel with pierced holes around its neck, challenging users to drink without spilling the contents on themselves

- Shishi-odoshi (lit. "animal scarer") a traditional device found in Japanese gardens, with a bamboo tube that gradually fills with water and then tilts to drain, making a clanking sound to scare away any crop-eating animals

References

- The Divine Classic of Nan-Hua; Being the Works of Chuang Tsze, Taoist Philosopher. Translated by Balfour, Frederic Henry. Kelly & Walsh. 1881.

- Chiu, Wai Wai (2015). "Goblet Words and Indeterminacy: A Writing Style that Is Free of Commitment". Frontiers of Philosophy in China. 10 (2): 255–272.

- Chong, Kim-Chong (2006). "Zhuangzi and the Nature of Metaphor". Philosophy East and West. 56 (3): 370–391. doi:10.1353/pew.2006.0033. S2CID 144833232.

- De Reu, Wim (2017). "On Goblet Words: Coexistence and Writing in the Zhuangzi". NTU Philosophical Review. 53: 75–108.

- Fox, Alan (2015). "Zhuangzi's Weiwuwei Epistemology: Seeing through Dichotomy to Polarity". In Livia Kohn (ed.). New Visions of the Zhuangzi. Three Pines Press. pp. 59–70.

- Fried, Daniel (2007). "A Never-Stable Word: Zhuangzi's Zhiyan and 'Tipping-Vessel' Irrigation". Early China. 31: 145–170. doi:10.1017/S0362502800001826. ISSN 0362-5028. S2CID 171249240.

- Chuang Tzu; Mystic, Moralist, and Social Reformer. Translated by Giles, Herbert A. (2nd ed.). Kelly & Walsh. 1926.

- Griffith, J. (2017). "From leaky pots to spillover-goblets: Plato and Zhuangzi on the responsiveness of knowledge". Dao, A Journal of Comparative Philosophy. 16 (2): 221–233.

- Chuang-tzu; The Seven Inner Chapters and other writings from the book Chuang-tzu. Translated by Graham, A.C. George Allen & Unwin. 1981.

- Kirby, Christopher (2019). "Goblet Words and Moral Knack: Non-Cognitive Moral Realism in the Zhuangzi?". In Colin Marshall (ed.). Comparative Metaethics: Neglected Perspectives on the Foundations of Morality (PDF). Routledge. pp. 159–178.

- Lau, D.C. (1966). On the Term ch'ih ying and the Story Concerning the So-called 'Tilting Vessel' (ch'i ch'i). Hong Kong University Fiftieth Anniversary Collection. III: pp. 18–33.

- F. Max Muller, ed. (1891). "The Texts of Taoism". The Sacred Books of the East. Translated by Legge, James. (2 vols.). Oxford University Press. pp. 39–40.

- Lin, Shuen-fu (1994). "The Language of the 'Inner Chapters' of the Chuang Tzu". In Willard J. Petersen; Andrew Plaks; Ying-shih Yu (eds.). The Power of Culture: Studies in Chinese Cultural History. The Chinese University Press. pp. 47–69. ISBN 9789622015968.

- Wandering on the Way, Early Taoist Tales and Parables of Chuang Tzu. Translated by Mair, Victor H. Bantam. 1994.

- Rapp, Jennifer R. (2010). "A Poetics of Comparison: Euripides, Zhuangzi, and the Human Poise of Imaginative Construction". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. 78 (1): 163–201. doi:10.1093/jaarel/lfp092.

- Tucker, John Allen (1984). "Goblet Words: The Chuang-tzu's Hermeneutic on Words and the Tao". Chinese Culture. 25 (4): 19–33.

- Wang, Youru (2004). "The Strategies of 'Goblet Words': Indirect Communication in the Zhuangzi". Journal of Chinese Philosophy. 31 (2): 195–218. doi:10.1163/15406253-03102003. Revised into the following 2014 book chapter.

- Wang, Youru (2014). "The Pragmatics of 'Goblet Words': Indirect Communication in the Zhuangzi". Linguistic Strategies in Daoist Zhuangzi and Chan Buddhism: The Other Way of Speaking. Routledge. pp. 139–160.

- The Sayings of Chuang Chou. Translated by Ware, James R. New American Library. 1963.

- The Complete Works of Chuang Tzu. Translated by Watson, Burton. Columbia University Press. 1968.

- Wu, Kuang-Ming (1988). "Goblet Words, Dwelling Words, Opalescent Words – Philosophical Methodology of Chuang Tzu". Journal of Chinese Philosophy. 15 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1163/15406253-01501001.

- Yearly, Lee H. (2005). "Daoist Presentation and Persuasion: Wandering among Zhuangzi's Kinds of Language". The Journal of Religious Ethics. 33 (3): 503–535. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9795.2005.00232.x.

Footnotes

- Yearly 2005, p. 503; Kirby 2019, p. 163.

- Tr. Steele, John C., (1917), The Yi- li: or Book of Etiquette and Ceremonial, Probsthain. p. 79.

- Tr. Fried 2007, p. 154.

- Lin 1994, p. 62.

- Wang Guowei (王国維) (1923), Guantang jilin (觀堂集林, Collected writings of [Wang Guowei]), 4 vols., Zhonghua. 6: 291-3.

- Rong Geng (容庚) (1941), Shang Zhou yiqi tongkao (商周彝器通考, Comprehensive studies on Shang and Zhou ritual vessels), 2 vols., Harvard-Yenching. p. 404.

- Needham, Joseph and Huang Hsing-Tsung (2000), Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 6 Biology and Biological Technology, Part 5: Fermentations and Food Science, Cambridge University Press. p. 103.

- Kroll, Paul K. (2017), A Student's Dictionary of Classical and Medieval Chinese, rev. ed., Brill. p. 603.

- For more on how these overlap see Morrow, C.M. (2016). "Metaphorical Language in the Zhuangzi". Philosophy Compass. 11 (4): 179–188. doi:10.1111/phc3.12314.

- Mair 1994.

- Lin 1994, p. 61.

- Mair 1994, pp. 278–9.

- Mair 1994, pp. 17, 231.

- Tucker 1984, p. 29.

- Mair 1994, p. 343.

- Tucker 1984, pp. 23–4.

- Guo and Zhang, 2018, p. 52.

- Tr. Moeller and Wohlfart, 2014, p. 67.

- Graham 1981, p. 277.

- Legge 1891, pp. 142–3, 228.

- Balfour 1881.

- Legge 1891.

- Giles 1926.

- Ware 1963.

- Watson 1968.

- Graham 1981.

- Zhuangzi: The Essential Writings with Selections from Traditional Commentaries. Translated by Ziporyn, Brook. Hackett Publishing. 2009.

- Balfour 1881, Legge 1891, Mair 1994.

- Watson 1968, p. 303.

- Graham 1981, p. 107.

- Balfour 1881, Ware 1963, Mair 1994.

- Graham 1981, p. 106.

- Wu 1988, p. 5.

- Giles 1926, p. 363.

- Graham 1981, p. 26.

- Mair 1994, p. 376.

- Tr. Fried 2007, p. 149.

- Yearly 2005, p. 505.

- Fried 2007, p. 150.

- Rapp 2010.

- Griffith 2017.

- Wang 2014.

- van Els, Paul (2012). "Tilting Vessels and Collapsing Walls—On the Rhetorical Function of Anecdotes in Early Chinese Texts" (PDF). Extrême-Orient, Extrême-Occident. 34: 141–166.

- Lau 1966, pp. 25–6.

- Tucker 1984, p. 26.

- Lin 1994, p. 65.

- Yearly 2005, p. 504.

- Yearly 2005, p. 531.

- Chong 2006, p. 370.

- Zhang Ling 張領 (1958), "Jiandi zhonger ping he 'qiqi' de guanxi" 尖底中耳瓶和'欹器'的關係, Shanxi shifan xueyuan xuebao 山西師範學院學報1: 45–48.

- Fried 2007, p. 163.

- Fried 2007, p. 155.

- Fried 2007, p. 165.

- Fried 2007, p. 166.

- Wang 2014, p. 147.

- Rapp 2010, p. 193.

- Wang 2014, p. 104.

- Wang 2014, p. 139.

- Anderson, E. N. (2014), Food and Environment in Early and Medieval China, University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 105.

- Mair 1994, p. 277.

- Fox 2015, p. 66.

- Mair 1994, p. 279.

- Fox 2015, p. 67.

- Chiu 2015, p. 259.

- Mair 1994, p. 15.

- Chiu 2015, p. 261.

- Mair 1994, p. 19.

- Chiu 2015, p. 263.

- Mair 1994, pp. 22–3.

- Chiu 2015, p. 267.

- Plato (1921). Plato. Translated by Harold N. Fowler. W. Heinemann. p. 191.

- Griffith 2017, p. 225.

- E.g., Wang 2004, Yearly 2005, Fried 2007; and Chiu 2015.

- E.g., Fried 2007 and Chiu 2015.

- Yearly 2005; Wang 2014; De Reu 2017, p. 78.

- De Reu 2017, p. 81.

- Mair 1994, p. 99-100.

- Kirby 2019, p. 161.

- Kirby 2019, p. 173.

- Fried 2007.

- Kirby 2019, p. 163.

External links

- Koo Hao Wei (2018), Zhuangzi's "Perfect Words" – A Variation of "Goblet Words", Nanyang Philosophy Review.

- Ray, Tyler (2012), Putting the World Outside Himself: Metaphorical Meaning in the Zhuangzi, Chrestomathy.