Golden hamster

The golden hamster or Syrian hamster (Mesocricetus auratus) is a rodent belonging to the hamster subfamily, Cricetinae.[2] Their natural geographical range is in an arid region of northern Syria and southern Turkey. Their numbers have been declining in the wild due to a loss of habitat from agriculture and deliberate elimination by humans.[1] Thus, wild golden hamsters are now considered endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.[3] However, captive breeding programs are well-established, and captive-bred golden hamsters are often kept as small house pets. They are also used as scientific research animals.

| Golden hamster | |

|---|---|

| |

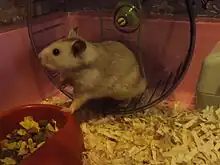

| A female pet hamster | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Rodentia |

| Family: | Cricetidae |

| Subfamily: | Cricetinae |

| Genus: | Mesocricetus |

| Species: | M. auratus |

| Binomial name | |

| Mesocricetus auratus Waterhouse, 1839 | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Cricetus auratus | |

Syrian hamsters are larger than many of the dwarf hamsters kept as pocket pets (up to five times larger), though the wild European hamster exceeds Syrian hamsters in size.

Characteristics

Adult golden hamsters can reach around 7.1 in (18 cm) long. Females are usually larger than males, with a body mass of around 100–150 grams (3.5–5.3 oz) and lifespan of 2-3 years. Syrian hamsters from private breeders can be in the range of 175–225 grams (6.2–7.9 oz).[4]

Like most members of the subfamily, the golden hamster has expandable cheek pouches, which extend from its cheeks to its shoulders. In the wild, hamsters are larder hoarders; they use their cheek pouches to transport food to their burrows. Their name in the local Arabic dialect where they were found roughly translates to "mister saddlebags" (Arabic: أبو جراب) due to the amount of storage space in their cheek pouches.[5]

Sexually mature female hamsters come into heat (estrus) every four days. Golden hamsters and other species in the genus Mesocricetus have the shortest gestation period in any known placental mammal at around 16 days. Gestation has been known to last up to 21 days, but this is rare and almost always results in complications. They can produce large litters of 20 or more young, although the average litter size is between eight and 10 pups. If a mother hamster is inexperienced or feels threatened, she may abandon or eat her pups. A female hamster enters estrus almost immediately after giving birth, and can become pregnant despite already having a litter. This act puts stress on the mother's body and often results in very weak and undernourished young.

Discovery

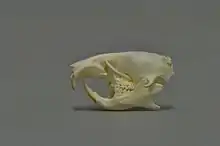

Golden hamsters originate from Syria and were first described by science in the 1797 second edition of The Natural History of Aleppo, a book written and edited by two Scottish physicians living in Syria.[6] The Syrian hamster was then recognized as a distinct species in 1839 by British zoologist George Robert Waterhouse, who named it Cricetus auratus or the "golden hamster". The skin of the holotype specimen is kept at the Natural History Museum in London.[7]

In 1930, Israel Aharoni, a zoologist and professor at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, captured a mother hamster and her litter of pups in Aleppo, Syria. The hamsters were bred in Jerusalem as laboratory animals.

Descendants of the captive hamsters were shipped to Britain in 1931, where they came under the care of the Wellcome Bureau of Scientific Research. These bred and two more pairs were given to the Zoological Society of London in 1932. The descendants of these were passed on to private breeders in 1937. A separate stock of hamsters was exported from Syria to the United States in 1971, but mitochondrial DNA studies have established that all domestic golden hamsters are descended from one female – likely the one captured in 1930 in Syria.[8]

Since the species was named, the genus Cricetus has been subdivided and this species (together with several others) was separated into the genus Mesocricetus, leading to the currently accepted scientific name for the golden hamster of Mesocricetus auratus.[9]

Behavior

Hamsters are very territorial and intolerant of each other; attacks against each other are commonplace. Exceptions do occur, usually when a female and male meet when the female is in heat, but even so, the female may attack the male after mating. In captivity, babies are separated from their mother and by sex after four weeks, as they sexually mature at four to five weeks old. Same-sex groups of siblings can stay with each other until they are about eight weeks old, at which point they will become territorial and fight with one another, sometimes to the death. Infanticide is not uncommon among female golden hamsters. In captivity, they may kill and eat healthy young as a result of the pups interacting with humans, for any foreign scent is treated as a threat. Females also eat their dead young in the wild.[10]

Golden hamsters mark their burrows with secretions from special scent glands on their hips called flank glands. Male hamsters in particular lick their bodies near the glands, creating damp spots on the fur, then drag their sides along objects to mark their territory. Females also use bodily secretions and feces.

Survival in the wild

Following Professor Aharoni's collection in 1930, only infrequent sightings and captures were reported in the wild. Finally, to confirm the current existence of the wild golden hamster in northern Syria and southern Turkey, two expeditions were carried out in September 1997 and March 1999. The researchers found and mapped 30 burrows. None of the inhabited burrows contained more than one adult. The team caught six females and seven males. One female was pregnant and gave birth to six pups. All these 19 caught golden hamsters, together with three wild individuals from the University of Aleppo, were shipped to Germany to form a new breeding stock.[11]

Observations of females in this wild population have revealed, contrary to laboratory populations, activity patterns are crepuscular rather than nocturnal, possibly to avoid nocturnal predators such as owls.[12] Owls, however, have also evolved to hunt at dusk and dawn, and even during the day on rare occasions, so the predator avoidance advantage may not apply to owls in particular. Another theory is that hamsters, which are extremely sensitive to temperature fluctuations, may be crepuscular to avoid the extreme temperatures of full daylight and night time temperatures.[13]

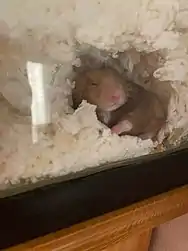

Golden hamsters in captivity run two to five miles per 24-hour period and can store up to one ton of food in a lifetime. They keep their food carefully separated from their urination and nesting areas. Very old hamsters with weak teeth break this "rule" by soaking hard seeds and nuts with urine to soften them for eating. Hamsters are extraordinary housekeepers and often sort through their hoards to clean and get rid of molding or rotting food. They gather food in the wild by foraging and carrying it home in their cheek pouches, which they empty by pushing it out through their open mouths, from back to front, with their paws, until it is empty. If a lot of food is available to carry, they may stuff the pouches so full that they cannot even close their mouths. Wild hamsters possibly behave similarly to those in captivity.[13]

As research animals

Golden hamsters are used to model human medical conditions including various cancers, metabolic diseases, non-cancer respiratory diseases, cardiovascular diseases, infectious diseases, and general health concerns.[14] In 2006 and 2007, golden hamsters accounted for 19% of the total Animal Welfare Act-covered animal research subjects in the United States.[15]

As pets

Golden hamsters are popular as house pets due to their docile, inquisitive nature, cuteness, and small size. However, these animals have some special requirements that must be met for them to be healthy. Although some people think of them as a pet for young children, the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals recommends hamsters as pets only for people over age 6 and the child should be supervised by an adult.[16] Cages should be a suitable size, safe, comfortable, and interesting. If a hamster is constantly chewing and/or climbing on the bars of its cage then it needs more stimulation or a larger cage. The minimum recommended size for a hamster cage is 775 square inches (5,000 cm2), of continuous floor space (although the source of this recommendation is unknown). These can be made by cutting and connecting large plastic storage bins, or a large glass tank. Appropriately sized wooden cages can be made, or bought online. The majority of hamster cages sold in pet stores do not meet these size requirements. Hamster Society Singapore (HHS) recommends a minimum of 4,000 square centimetres (620 sq in) for Syrian hamsters,[17] while Tierärztliche Vereinigung für Tierschutz (TVT) recommends giving them as much space as you can and at minimum 100 cm × 50 cm × 50 cm (L × W × H) which is 5,000 cm2 (780 sq in).[18]

A hamster wheel is a common type of environmental enrichment, and it is important that hamsters have a wheel in their cage. TVT recommends wheels should be at least 30 cm for Syrian hamsters, since smaller diameters lead to permanent spinal curvatures, especially in young animals. They also recommend a solid running surface because rungs or mesh can cause injury, or bumblefoot.[19] A hamster should be able to run on its wheel without arching its back. A hamster that has to run with an arched back can have back pain and spine problems. A variety of toys and cardboard tubes and boxes can help to provide enrichment, as they are energetic and need space to exercise.[20]

Most hamsters in American and British pet stores are golden hamsters. Originally, golden hamsters occurred in just one color – the mixture of brown, black, and gold, but they have since developed a variety of color and pattern mutations, including cream, white, blonde, cinnamon, tortoiseshell, black, three different shades of gray, dominant spot, banded, and dilute.

Breeding

The practice of selective breeding of golden hamsters requires an understanding of their care, knowledge about breed variations, a plan for selective breeding, scheduling of the female body cycle, and the ability to manage a colony of hamsters.

Breed variations

Often long-haired hamsters are referred to by their nickname "teddy bear". They are identical to short-haired Syrians except for the hair length and can be found in any color, pattern, or other coat type available in the species. Male long-haired hamsters usually have longer fur than the female, culminating in a "skirt" of longer fur around their backsides. Long-haired females have a much shorter coat although it is still significantly longer than that of a short-haired female.

See also

- Turkish hamster

- Romanian hamster

- Hamster racing

- Winter white dwarf hamster

- Roborovski dwarf hamster

- Campbell's dwarf hamster

- Martin R. Ralph (for experiments done with golden hamsters and their circadian rhythms)

References

- Kennerley, R.; Middleton, K. (2022). "Mesocricetus auratus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022: e.T13219A107411865. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- Musser, G.G.; Carleton, M.D. (2005). "Superfamily Muroidea". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 1044. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- "The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species – Golden Hamster". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- "Guldhamster". Svenska Hamsterföreningen. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- Dunn, Rob (24 March 2011). "The Untold Story of the Hamster, a.k.a Mr. Saddlebags". Smithsonianmag.com.

- Murphy, Michael R. (1985). "History of the Capture and Domestication of the Syrian Golden Hamster (Mesocricetus auratus Waterhouse)". In Siegel, Harold I. (ed.). The Hamster: reproduction and behavior. New York: Plenum Press. ISBN 030641791X.

- Henwood, Chris (2001). "The Discovery of the Syrian Hamster, Mesocricetus auratus". The Journal of the British Hamster Association (39). Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- Sykes, Brian (2001). The Seven Daughters of Eve: The Science That Reveals Our Genetic Ancestry. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 57–62. ISBN 978-0-00-712282-0.

- Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M., eds. (2005). "Mesocrictus". Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Siegel, Harold I.; Rosenblatt, Jay S. (1980). "Hormonal and behavioral aspects of maternal care in the hamster: A review". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 4 (1): 17–26. doi:10.1016/0149-7634(80)90023-8. ISSN 0149-7634. PMID 6995872. S2CID 10591609.

- Gattermann, R.; Fritzsche, P.; Neumann, K.; Al-Hussein, I.; Kayser, A.; Abiad, M.; Yakti, R. (2001). "Notes on the current distribution and the ecology of wild golden hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus)". Journal of Zoology. Cambridge University Press. 254 (3): 359–365. doi:10.1017/S0952836901000851.

- Gattermann, R.; Johnston, R. E.; Yigit, N; Fritzsche, P; Larimer, S; Ozkurt, S; Neumann, K; Song, Z; et al. (2008). "Syrian hamsters are nocturnal in captivity but diurnal in nature". Biology Letters. 4 (3): 253–255. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2008.0066. PMC 2610053. PMID 18397863.

- Stacey OBrien; field notes

- Valentine et al. 2012, p. 875-898.

- United States Department of Agriculture (September 2008), Animal Care Annual Report of Activities – Fiscal Year 2007 (PDF), United States Department of Agriculture, retrieved 14 January 2016

- "Hamster Care" (PDF). American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. 2010.

- Hamster Society Singapore

- Tierärztliche Vereinigung für Tierschutz e.V., Merkblatt Nr. 156 – Heimtiere: Goldhamster (Stand: 2014), pets: golden hamster, Housing

- Tierärztliche Vereinigung für Tierschutz e.V., Merkblatt Nr. 62 – Heimtierhaltung, Tierschutzwidriges Zubehör (Stand: Jan. 2010), II. Anti-animal welfare accessories for small mammals, 7. Wheels

- Alderton, David (2002). Hamster. Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-712282-0.

Sources

- Valentine, Helen; Daugherity, Erin K.; Singh, Bhupinder; Maurer, Kirk J. (2012). "The Experimental Use of Syrian Hamsters". In Suckow, Mark A.; Stevens, Karla A.; Wilson, Ronald P. (eds.). The laboratory rabbit, guinea pig, hamster, and other rodents (1st. ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier Academic Press. pp. 875–898. ISBN 978-0123809209.