Golden Hat of Schifferstadt

The Golden Hat of Schifferstadt (German: Der Goldene Hut von Schifferstadt) was discovered in a field near the town of Schifferstadt in Southwest Germany in 1835. It is a Bronze Age artefact made of thin sheet gold and served as the external decoration of a head-dress, probably of an organic material, with a brim and a chin-strap. The hat is on display in the Historical Museum of the Palatinate in Speyer. It is one of a group of four similar artifacts known as the Golden hats, all cone-shaped Bronze Age head-dresses made of sheet gold.

Cultural context

The Schifferstadt specimen is the oldest of the group of four known Golden hats and was the first to be discovered. After the example from Berlin, it is the best-preserved one, fully preserved with the exception of a small part of the brim.

Three associated bronze axes and a comparison with other Late Bronze Age metalwork date the Schifferstadt Hat to circa 1,400-1,300 BC.

The hat, like its counterparts, is assumed to have served as a religious insignia for the deities or priests of a sun-cult common in Bronze Age Europe. The hats are also suggested to have served calendrical functions.

Description

The Schifferstadt Hat is a 350 g gold cone, subdivided into horizontal ornamental bands, applied in the repoussé technique. It has a blunt, undecorated tip. The shaft is short and squat, with a distinct widening and a wide brim at the bottom. The hat is 29.6 cm high and has a lower diameter of about 18 cm. The brim is 4.5 cm wide. At its base the gold sheet was wound around a copper wire (now lost) for extra stability.

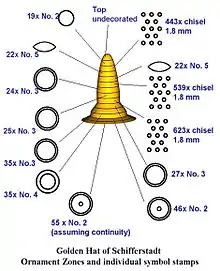

Along its whole length the hat is subdivided and decorated by rows of horizontal symbols and bands. Five different stamps and a chisel or liner were used to create the horizontal bands of repeated stamped symbols, following a systematic scheme.

The optical separation of the individual ornamental bands was achieved by ring ribs or bands around the whole external face of the hat. The symbols in the bands are mostly disk and circle motifs, usually with an internal disk or buckle, surrounded by up to six concentric circles.

Striking are two bands with eye-like motifs, resembling similar symbols on the hats of Ezelsdorf and Berlin. Unlike the other known examples, the cone's top is not decorated with a star but left entirely unembellished.

The illustration shows the scheme of the shape and composition of the hat, as well as number of ornamental zones and of the number of stamps used for each.

Provenance and find history

The Golden Hat of Schifferstadt was discovered on 29 April 1835, during agricultural work in a field named Reuschlache, one km north of Schifferstadt. On the following day the find was handed to officials at Speyer, then part of the Kingdom of Bavaria.

The known circumstances suggest a cult-related deposition: The hat was buried upright, about 60 cm deep. Its top reached to just below the ground surface. When found the hat stood on a slab of back-burnt clay. It was filled with earth or an earth-ashes mixture, of which nothing remains.

The clay slab, which crumbled during its recovery and is now entirely lost, sat on a one-inch layer of sand, placed in a rectangular pit. Three bronze axes were leaning against the cone.

Manufacture

The hat is hammered from a single piece of gold alloy of 86.37% Au, 13% Ag, 0.56% Cu and 0.07% Sn. Its average thickness is 0.2 to 0.25 cm, except the brim, which is far thinner, at 0.08 to 0.13 mm. The latter may suggest that it had been re-worked at some stage.

If the amount of gold used for the hat was moulded into a square bar, it would only measure 2.5 cm square. Such a bar or lump was hammered to the thickness of a modern sheet of printing paper during its production.

Because of the tribological characteristics of the material, it tends to harden with increasing deformation (see ductility), increasing its potential to crack. To avoid cracking, an extremely even deformation was necessary. Additionally, the material had to be softened by repeatedly heating it to a temperature of at least 750 °C.

Since gold alloy has a relatively low melting point of circa 960 °C, a very careful temperature control and an isothermal heating process were required, so as to avoid melting any of the surface. For this, the Bronze Age artisans used a charcoal fire or oven similar to those used for pottery. The temperature could only be controlled through the addition of oxygen, using a bellows.

In the course of its further manufacture, the hat was embellished with rows of radial ornamental bands, chased into the metal. To make this possible, it was filled with a putty or pitch based on tree resin and wax, traces of which have survived. The thin gold leaf was structured by chasing: stamp-like tools or moulds depicting the individual symbols were repeatedly pressed into (or rolled along) the exterior of the gold.

See also

- Golden hats

- Berlin Gold Hat, circa 1,000 – 800 BC

- Golden Cone of Ezelsdorf-Buch, circa 1,000 – 800 BC

- Avanton Gold Cone, circa 1,000 – 900 BC

- Nebra skydisk, circa 2,100 – 1,700 BC

Bibliography

- Gold und Kult der Bronzezeit. (Ausstellungskatalog). Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nürnberg 2003. ISBN 3-926982-95-0

- Wilfried Menghin (ed.): Acta Praehistorica et Archaeologica. Unze, Potsdam 32.2000, S. 31-108. ISSN 0341-1184

- Peter Schauer: Die Goldblechkegel der Bronzezeit – Ein Beitrag zur Kulturverbindung zwischen Orient und Mitteleuropa. Habelt, Bonn 1986. ISBN 3-7749-2238-1

- Gerhard Bott (Hrsg.): Der Goldblechkegel von Ezelsdorf. (Ausstellungskatalog). Theiß, Stuttgart 1983. ISBN 3-8062-0390-3

- Mark Schmidt: Von Hüten, Kegeln und Kalendern oder Das blendende Licht des Orients. in: Ethnographisch-Archäologische Zeitschrift. Berlin 43.2002, p. 499-541. ISSN 0012-7477

- Ernst Probst: Deutschland in der Bronzezeit. Bauern, Bronzegießer und Burgherren zwischen Nordsee und Alpen. München 1999. ISBN 3-572-01059-4