Golden Years (David Bowie song)

"Golden Years" is a song by the English musician David Bowie, released by RCA Records on 21 November 1975 as the lead single from his tenth studio album Station to Station (1976). Partially written before Bowie began shooting for the film The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976), the song was mostly compiled in the studio and was the first track completed for the album. Co-produced by Bowie and Harry Maslin, recording took place at Cherokee Studios in Los Angeles during September 1975. Due to Bowie's heavy cocaine use, he later recalled remembering almost nothing of Station to Station's production.

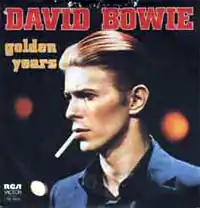

| "Golden Years" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Single by David Bowie | ||||

| from the album Station to Station | ||||

| B-side | "Can You Hear Me?" | |||

| Released | 21 November 1975 | |||

| Recorded | 21–30 September 1975 | |||

| Studio | Cherokee (Los Angeles) | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length |

| |||

| Label | RCA | |||

| Songwriter(s) | David Bowie | |||

| Producer(s) |

| |||

| David Bowie singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

Musically, "Golden Years" is a funk and disco song that is reminiscent of the music on Bowie's previous album, Young Americans (1975), particularly "Fame", but with a harsher, grinding edge. The song utilises elements of several 1950s doo-wop tracks in its arrangement. Lyrically, the narrator offers a companion hope of entering a limousine and being isolated from the outside world. In other words, he assures his companion that she will always be protected by him and promises her a brighter future.

"Golden Years" has been viewed positively by music critics and biographers, who have highlighted its composition. Bowie preceded its release by miming the song on Soul Train, where he appeared incoherent. Upon release, the song was a commercial success, peaking at number eight in the UK and number ten in the US. The song was rarely played throughout Bowie's 1976 Isolar tour but regularly on other tours. "Golden Years" has appeared on lists of Bowie's best songs and has been included on various compilation albums, covered by numerous artists and made appearances in several films and soundtracks, including A Knight's Tale (2001), which featured a new remix by Bowie's longtime collaborator Tony Visconti.

Background and recording

David Bowie started writing "Golden Years" in May 1975 before shooting commenced for the film The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976).[1] Sources differ as to whom the track was written for. Bowie's biographers state the track was supposedly written for American singer Elvis Presley, who turned it down.[2][3][4] Bowie recalled that Presley had heard the demos and, because both artists were signed to RCA Records at the time, Presley's manager Colonel Tom Parker thought that Bowie should write songs for Presley. Bowie stated that he had "adored" Presley and would have loved to work with him.[2] Although the artists' offices contacted each other, nothing ever came to fruition. Presley sent a note to Bowie saying, "All the best, and have a great tour"; Bowie kept the note for the rest of his life.[2] Conversely, Chris O'Leary states that the song was never presented to Presley due to stalled negotiations with Parker.[1] David's first wife Angie Bowie later claimed he wrote the song for her,[2][4] saying that he sang the track over the telephone to her, "just the way, all those years before, he'd sung me [his 1970 track] 'The Prettiest Star'. It had a similar effect. I bought it."[3] According to Christopher Sandford, Ava Cherry also claimed to have been the inspiration for the song.[4]

David Bowie's 1975 single "Fame", a collaboration with former Beatle John Lennon,[5][6] was a massive commercial success, topping the US Billboard Hot 100.[7] As such, RCA were eager for a follow-up. After completing his work on The Man Who Fell to Earth in September,[8] Bowie returned to Los Angeles to begin recording his next album. Personnel-wise, Bowie brought back the same team used for "Fame": co-producer Harry Maslin, guitarists Carlos Alomar and Earl Slick, drummer Dennis Davis and Bowie's old friend Geoff MacCormick (credited as Warren Peace), while bassist George Murray was recruited.[1][9] For the studio, Bowie and Maslin chose Los Angeles's Cherokee Studios,[10] a popular studio at the time that was more advanced than Philadelphia's Sigma Sound Studios, where Bowie had recorded Young Americans (1975); it featured five different studio rooms, 24-track mixing consoles, 24-hour session times, more space and a lounge bar.[1]

Recording for the new album began in late September 1975 and ended in November.[11] The prospective single "Golden Years" was the first track recorded,[2][12] between 21 and 30 September.[1] At one stage it was slated to be the album's title track. Regarding the recording, Maslin recalled that the song was "cut and finished very fast. We knew it was absolutely right within ten days. But the rest of the album took forever."[3] Like the majority of Station to Station, the song's elements were primarily built in the studio rather than written before.[13][14] MacCormick gave suggestions to Bowie for the song's arrangement, including the addition of the "WAH-wah-WAH" tags after the refrains and the "go-oh-oh-old" tags on the bridges. He also assisted Bowie on the backing vocal harmonies, recalling in his memoir: "When we came to record the backing vocals for the song, David lost his voice halfway through, leaving me to finish the job. That meant I had to sing the series of impossibly high notes before the chorus, which were difficult enough for David but were absolute murder for me."[1][3] Due to Bowie's heavy cocaine use during the sessions, he later recalled remembering almost nothing of the album's production.[15]

Composition and lyrics

Station to Station is commonly regarded as a transitional album in Bowie's career,[16] developing the funk and soul of Young Americans and introducing influences of electronic and the German music genre of krautrock, particularly bands such as Neu! and Kraftwerk, styles Bowie would further explore on his late 1970s Berlin Trilogy.[10][17] Like fellow album track "Stay", "Golden Years" is built upon the styles of Young Americans but with a harsher, grinding edge.[18] Nicholas Pegg states that the song lacks the "steelier musical landscape" of the rest of the album.[3] The song also utilises elements of 1950s doo-wop; the main guitar riff is based on the 1968 Cliff Nobles and Company song "The Horse" and the multi-tracked vocal refrain resembles the Diamonds' 1958 single "Happy Years".[1][3] Other tracks that influenced the composition of "Golden Years" included the Drifters' 1963 song "On Broadway", which Bowie played on piano during rehearsals, adding a "come buh-buh-buh baby" after each line, and Dyke and the Blazers' 1966 song "Funky Broadway" that Earl Slick used for a few riffs.[1][2] While the song overall permeates the styles of "Fame", O'Leary states that it blends elements of krautrock in the main guitar riff.[1] Commentators have categorised the song's sound as funk, disco, and doo-wop.[12][19][20][21][22]

"Golden Years" is in the key of B major and begins with a "simple two-chord" riff (F♯–E),[12] which David Buckley believes hooks the listener instantly.[2] Author Peter Doggett calls the riff "reminiscent"–albeit "in very different circumstances"–to the title track of Bowie's Aladdin Sane (1973). He writes: "The magical ingredients were percussive: the rattling of sticks against the hi-hat cymbal from the start, the startling clack of woodblocks, the sudden drum fills." According to him, these combined elements "channel" the spirit of Presley in the verses, with a "haughtier, more strident tone" in the chorus.[12] The song features what O'Leary calls "dueling guitars", both mixed into separate channels: the right one plays variations on the opening riff throughout while the left one plays a "gliding rhythm", echoing the "WAH-wah-WAH" with a three-chord riff after the bridges.[1]

The song's structure is unique, in that the bridges vary between two and six bars. The longer bridge features a chord progression from G major ("nothing's gonna touch you") to A minor ("golden") then an E minor 7th ("years"), ending with a 2/4 cut time bar. Here, Bowie sings "go-oh-oh-old" while Murray's bass overlays a Moog synthesiser. There is also prevalent percussion throughout, including handclaps, vibraslap and melodica. O'Leary finds Bowie almost rapping in the third verse during the lines up to "all the WAY" (sung in F♯), which is followed by the "run for the shadows" phrases before another chorus.[1]

Biographer Marc Spitz interprets Station to Station as "an album of love songs", specifically "the kind you write when you have no love in your own life".[23] Indeed, James Perone considers "Golden Years" the type of love song that doesn't feature the word love.[18] In the song, the narrator offers a companion hope of entering a limousine and being sealed off from the outside world.[1] In other words, he assures his companion that he will always protect her no matter what and promises her a brighter future.[18] NME editors Roy Carr and Charles Shaar Murray find that the lyric carry "an air of regret for missed opportunities and past pleasures".[10] O'Leary states that Bowie's life in Los Angeles influenced the lyrical writing.[1]

Promotion and release

On 4 November 1975, Bowie appeared on the American television show Soul Train, miming "Fame" and the then-unreleased "Golden Years". Bowie was the second white artist to appear on the programme, after Elton John six months earlier.[24] During the performance and interview, he was visibly intoxicated and,[25] according to Pegg, was at a "new low in coherency". Bowie later felt ashamed for his behaviour, recalling in 1999 that he had failed to learn "Golden Years" and was scolded afterwards by the show's DJ.[24] Spitz describes the appearance as "canny" and "awkward",[23] while O'Leary calls it Bowie's "loneliest, saddest television appearance".[1] The resulting film clip was used as the song's unofficial music video for promotion worldwide.[3] Like the relationship of "Rebel Rebel" with Diamond Dogs (1974), "Golden Years" was a somewhat unrepresentative teaser for the then-upcoming album.[3][21]

RCA released "Golden Years" as the lead single from Station to Station on 21 November 1975 while the album was still being finished.[1] Its B-side was the Young Americans track "Can You Hear Me?" with the catalogue number was RCA 2640;[26] it featured a length of 3:30.[3] The song subsequently appeared as the second track on Station to Station, between the title track and "Word on a Wing",[26] with a longer length of 4:03.[20] According to Pegg, the single version is "essentially" the album version with an earlier fade.[3] The song would later appear as the B-side of fellow Station to Station track "Wild Is the Wind" in November 1981.[27] An updated single version of "Golden Years" was released in 2011 to coincide with the re-release of Station to Station. Four new remixes were provided by DJs from radio station KCRW in California.[3]

Following "Fame", "Golden Years" continued Bowie's commercial success.[3] In the UK, where it was "hard on the heels" of the chart-topping "Space Oddity" reissue,[3] the single peaked at number eight on the UK Singles Chart, remaining on the chart for 10 weeks.[28] In the US, it charted for 16 weeks on the Billboard Hot 100 and reached number 10,[29] also peaking at number 12 on the Cash Box Top 100.[30] The song further peaked at number 17 on the Canadian RPM Top Singles chart,[31] number 34 on the Australian Kent Music Report,[32] and number 18 on the New Zealand Listener chart.[33] Following Bowie's death in 2016, the song charted in numerous countries, including in France (193) and Belgium Wallonia region (28),[34][35] alongside scoring top-10 positions in Belgium Flanders region (10),[36] Sweden (10),[37] Ireland (9),[38] and the Netherlands (6).[39]

Critical reception

"Golden Years" has received positive reviews from music critics and biographers, who highlight its composition. Reviewing Station to Station on release, John Ingham of Sounds magazine gave heavy praise to the album, naming "Golden Years", "TVC 15" and "Stay" some of Bowie's best songs up to that point.[40] Meanwhile, Rolling Stone writer Teri Moris considered the track "Bowie's most seductive self-indulgence since Pin Ups [1973]".[41] A reviewer for Billboard felt Bowie had "found his musical niche" with songs like "Fame" and "Golden Years".[42] Record World said that the song has "a rather unadorned style and generates a basic appeal."[43]> In his book Starman, biographer Paul Trynka calls "Golden Years" "magnificent [and] sensitive", stating that the track "reflects Bowie's ability to surface from a cocaine jag and dispense insightful career advice or relate a hilariously deadpan joke".[14] Additionally, Buckley considers the song one of Bowie's best singles.[2]

The song has appeared on several lists of Bowie's greatest songs. Mojo magazine listed it as Bowie's 11th greatest song in 2015.[44] In a 2016 list ranking every Bowie single from worst to best, Ultimate Classic Rock placed "Golden Years" at number 11, calling it "a taste of [the album's] brilliance".[45] In 2018, the staff of NME placed the track at number 16 in a list of Bowie's 40 best songs.[46] Two years later, Tom Eames of Smooth Radio listed it as Bowie's 13th greatest song.[47] That same year, The Guardian's Alexis Petridis voted the track number 14 in his list of Bowie's 50 greatest songs, describing it as, "A moment of straightforward joy amid the complex, troubled emotional terrain of Station to Station."[48]

Live performances and subsequent releases

"Golden Years" was played sporadically by Bowie on his 1976 Isolar tour.[3] According to Thomas Jerome Seabrook, this was because Bowie struggled to sing it.[49] The song later made regular appearances on the 1983 Serious Moonlight, 1990 Sound+Vision, and 2000 Mini tours.[3] Live performances of the song from the Serious Moonlight tour and Glastonbury Festival appear in Serious Moonlight (1983) and Glastonbury 2000 (2018), respectively.[50][51]

"Golden Years" has appeared on several compilation albums, including Changesonebowie (1976),[52] The Best of Bowie (1980),[53] Changesbowie (1990),[54] The Singles Collection (1993),[55] The Best of David Bowie 1974/1979 (1998),[56] Best of Bowie (2002),[57] The Platinum Collection (2006),[58] Nothing Has Changed (2014),[59] and Legacy (The Very Best of David Bowie) (2016).[60][61] In 2016, the song was remastered, along with its parent album, as part of the Who Can I Be Now? (1974–1976) box set. The song's single edit was also included on Re:Call 2, part of that set.[62][63] A new remix of the song by DJ Tokimonsta was released as a digital single in May 2023.[64]

Cover versions and appearances in media

In February 1976, English comedians Peter Glaze and Jan Hunt covered "Golden Years" for the BBC children's television series Crackerjack!. Pegg calls this rendition "unquestionably the most peculiar version – and a strong contender for the most bizarre rendition of a Bowie song ever performed".[3] American singer Marilyn Manson later covered the song for the 1998 film Dead Man on Campus, while James Murphy of LCD Soundsystem, who remixed Bowie's 2013 track "Love Is Lost" and worked with him for his final album Blackstar (2016),[65] recorded a version for the 2014 film While We're Young.[3]

The song has made appearances in several films and soundtracks, including on Trainspotting #2: Music from the Motion Picture, Vol. #2 (1997).[66] An instrumental version of Bowie's original appeared in the closing credits of the American limited series Stephen King's Golden Years (1991),[3] while the standard track was included on the original soundtrack of Brian Helgeland's 2001 film A Knight's Tale. The song appeared in a new remix by Bowie's longtime collaborator Tony Visconti, where it gradually replaces the medieval soundtrack as, in Pegg's words, "a courtly farandole develops into a disco freak-out".[3] Cultural critic Anthony Lane called the film's use of "Golden Years" "the best and most honest use of anachronism that I know of".[67]

Personnel

According to biographer Chris O'Leary:[1]

- David Bowie – lead and backing vocals, handclaps, melodica, Moog synthesiser, producer

- Carlos Alomar – lead and rhythm guitar

- Earl Slick – lead and rhythm guitar

- George Murray – bass

- Dennis Davis – drums, vibraslap

- Warren Peace – percussion, backing vocals

- Harry Maslin – producer

Charts

Weekly charts

|

Year-end charts

|

Certifications

| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom (BPI)[75] | Silver | 200,000‡ |

|

‡ Sales+streaming figures based on certification alone. | ||

References

- O'Leary 2015, chap. 10.

- Buckley 2005, pp. 236–237.

- Pegg 2016, pp. 100–101.

- Sandford 1997, p. 146.

- Spitz 2009, p. 249.

- Buckley 2005, pp. 215–217.

- Pegg 2016, pp. 86–88.

- Seabrook 2008, p. 44.

- Pegg 2016, p. 380.

- Carr & Murray 1981, pp. 78–80.

- Cann, Kevin (2010). Station to Station (CD booklet). David Bowie (reissue ed.). EMI.

- Doggett 2012, pp. 288–289.

- Doggett 2012, p. 297.

- Trynka 2011, p. 487.

- Pegg 2016, p. 381.

- Perone 2007, pp. 50–51.

- Pegg 2016, p. 382.

- Perone 2007, pp. 52–53.

- Mojica, Frank (4 October 2010). "David Bowie – Station to Station [Special Edition]". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on 9 July 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Station to Station – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

...as well as the disco stylings of 'Golden Years'.

- Thompson, Dave. "'Golden Years' – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 7 June 2019. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- Breihan, Tom (26 August 2019). "The Number Ones: Johnnie Taylor's "Disco Lady"". Stereogum. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

...David Bowie's coked-out neo-doo-wop crab-funker "Golden Years" peaked at #10 behind "Disco Lady".

- Spitz 2009, pp. 267–268.

- Pegg 2016, pp. 565–566.

- Carr & Murray 1981, p. 75.

- O'Leary 2015, Partial Discography.

- O'Leary 2019, Partial Discography.

- "David Bowie – full Official Chart History". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- Whitburn, Joel (1991). Top Pop Singles 1955–1990. Menomonee Falls, Wisconsin: Record Research Inc. ISBN 978-0-89820-089-8.

- "Cash Box Top 100 Singles, March 27, 1976". Archived from the original on 20 October 2018. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- "Image : RPM Weekly – Library and Archives Canada". Bac-lac.gc.ca. Library and Archives Canada. 17 July 2013. Archived from the original on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992. St Ives, NSW: Australian Chart Book. ISBN 0-646-11917-6.

- "Flavour of New Zealand, 9 April 1976". Archived from the original on 23 September 2018. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- "David Bowie – Golden Years" (in French). Les classement single. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- "David Bowie – Golden Years" (in French). Ultratop 50. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- "David Bowie – Golden Years" (in Dutch). Ultratop 50. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- "David Bowie – Golden Years". Singles Top 100. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- "The Irish Charts – Search Results – Golden Years". Irish Singles Chart. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- "David Bowie – Golden Years" (in Dutch). Single Top 100. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- Ingham, John (24 January 1976). "David Bowie: Station to Station (RCA)". Sounds. Archived from the original on 3 October 2021. Retrieved 2 October 2021 – via Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- Moris, Teri (25 March 1976). "Station to Station". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 13 September 2017. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- "Top Album Picks" (PDF). Billboard. 31 January 1976. p. 56. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 June 2021. Retrieved 3 October 2021 – via worldradiohistory.com.

- "Hits of the Week" (PDF). Record World. 6 December 1975. p. 1. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- "David Bowie – The 100 Greatest Songs". Mojo (255). February 2015. Archived from the original on 9 September 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2021 – via rocklist.net.

- "Every David Bowie Single Ranked". Ultimate Classic Rock. 14 January 2016. Archived from the original on 24 July 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- Barker, Emily (8 January 2018). "David Bowie's 40 greatest songs – as decided by NME and friends". NME. Archived from the original on 3 November 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- Eames, Tom (26 June 2020). "David Bowie's 20 greatest ever songs, ranked". Smooth Radio. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- Petridis, Alexis (19 March 2020). "David Bowie's 50 greatest songs – ranked!". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- Seabrook 2008, p. 124.

- Pegg 2016, pp. 640–641.

- Collins, Sean T. (5 December 2018). "David Bowie: Glastonbury 2000 Album Review". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 11 July 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- Erlewine, Stephen Thomas (24 May 2016). "David Bowie: Changesonebowie Album Review". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 10 September 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- Pegg 2016, pp. 162–163.

- Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Changesbowie – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 28 July 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "The Singles: 1969–1993 – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "The Best of David Bowie 1974/1979 – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 6 October 2021. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Best of Bowie – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- Monger, James Christopher. "The Platinum Collection – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 8 May 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- Sawdey, Evan (10 November 2017). "David Bowie: Nothing Has Changed". PopMatters. Archived from the original on 14 July 2017. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- Monroe, Jazz (28 September 2016). "David Bowie Singles Collection Bowie Legacy Announced". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 26 September 2019. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- Trendell, Andrew (28 September 2016). "New David Bowie greatest hits album 'Bowie Legacy' set for release". NME. Archived from the original on 11 August 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- "Who Can I Be Now? (1974–1976) details". David Bowie Official Website. 22 July 2016. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- Gerard, Chris (28 September 2016). "David Bowie: Who Can I Be Now? (1974/1976)". PopMatters. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- "'Golden Years' (TOKiMONSTA remix) digital single out now". David Bowie Official Website. 5 May 2023. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- Pegg 2016, pp. 173, 473.

- Bush, John. "Trainspotting, Vol. 2 – Original Soundtrack". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 6 October 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- Lane, Anthony. "David Bowie in the Movies". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 25 October 2020. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- "Top RPM Singles: Issue 4101a." RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- "Nederlandse Top 40 – week 5, 1976" (in Dutch). Dutch Top 40. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- "Jaaroverzichten 1976". Ultratop. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- "Top Singles – Volume 26, No. 14 & 15, January 08 1977". RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- "Top 100-Jaaroverzicht van 1976". Dutch Top 40. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- "Jaaroverzichten – Single 1976". dutchcharts.nl. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- "Top 100 Hits of 1976/Top 100 Songs of 1976". Musicoutfitters.com. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- "British single certifications – David Bowie – Golden Years". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

Sources

- Buckley, David (2005) [1999]. Strange Fascination – David Bowie: The Definitive Story. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0-75351-002-5.

- Carr, Roy; Murray, Charles Shaar (1981). Bowie: An Illustrated Record. New York City: Avon. ISBN 0-380-77966-8.

- Doggett, Peter (2012). The Man Who Sold the World: David Bowie and the 1970s. New York City: HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 978-0-06-202466-4.

- O'Leary, Chris (2015). Rebel Rebel: All the Songs of David Bowie from '64 to '76. Winchester: Zero Books. ISBN 978-1-78099-244-0.

- O'Leary, Chris (2019). Ashes to Ashes: The Songs of David Bowie 1976–2016. London: Repeater. ISBN 978-1-91224-830-8.

- Pegg, Nicholas (2016). The Complete David Bowie (Revised and Updated ed.). London: Titan Books. ISBN 978-1-78565-365-0.

- Perone, James E. (2007). The Words and Music of David Bowie. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-27599-245-3.

- Sandford, Christopher (1997) [1996]. Bowie: Loving the Alien. London: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80854-8.

- Seabrook, Thomas Jerome (2008). Bowie in Berlin: A New Career in a New Town. London: Jawbone Press. ISBN 978-1-90600-208-4.

- Spitz, Marc (2009). Bowie: A Biography. New York City: Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-71699-6.

- Trynka, Paul (2011). David Bowie – Starman: The Definitive Biography. New York City: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-31603-225-4.