Golden Age of India

Certain historical time periods have been named "golden ages", where development flourished, including on the Indian subcontinent.[1][2]

Ancient India

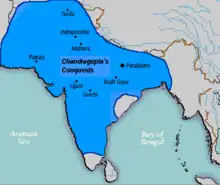

Maurya Empire

The Maurya Empire (321–185 BC) was the largest and one of the most powerful empires to exist in the history of the Indian subcontinent. This era was accompanied by high levels of cultural development and economic prosperity. The empire saw significant advancements in the fields of literature, science, art, and architecture. Important works like the Arthashastra and Sushruta Samhita were written and expanded in this period. The earlier development of the Brahmi script and Prakrit languages took place during this period, and these later formed the bases of other languages. This era also saw the emergence of scholars like Acharya Pingal and Patanjali, who made great advancements in the fields of mathematics, poetry, and yoga.[3] The Maurya Empire was notable for its efficient administrative system, which included a large network of officials and bureaucrats as well as a sophisticated system of taxation and a well-organized army.[4][5]

According to estimates given by historians, during the Maurya era, the Indian subcontinent generated close to one third of global GDP, which would be the highest the region would ever contribute.[6]

Gupta Empire

The period between the 4th and 6th centuries CE is known as the Golden Age of India because of the considerable achievements that were made in the fields of mathematics, astronomy, science, religion, and philosophy, during the Gupta Empire.[7] [8] The decimal numeral system, including the concept of zero, was invented in India during this period.[9] The peace and prosperity created under the leadership of the Guptas enabled the pursuit of scientific and artistic endeavors in India.[10][11][12] The Golden Age of India came to an end when the Hunas invaded the Gupta Empire, in the 6th century CE. The gross domestic product (GDP) of ancient India was estimated to be 32% and 28% of global GDP in 1 AD and 1000 AD, respectively.[13] Also, during the first millennium of the Common Era, the Indian population comprised around 30.3% and 27.15% of the total world population.[14] [15][16]

Medieval India

Chola Empire

South India in the 10th and 11th centuries CE, under the imperial Cholas, is considered as another golden age.[17][18] The period saw extensive achievements in architecture, Tamil literature, sculpture and bronze working, maritime conquests, and trade. Under the Cholas, the major Southeast Asian countries practiced Hinduism. Chola GDP constituted the world's largest GDP at that time.[19][18][20]

Vijayanagara Empire

Often regarded as one of the greatest Indian empires, the Vijaynagara Empire during the 14th to 16th century covered much of the region of South India, controlling the lands of the modern states of Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Goa, and some parts of Telangana and Maharashtra. It was established in 1336 by the brothers Harihara I and Bukka Raya I of the Sangama dynasty, members of a pastoralist cowherd community that claimed Yadava lineage.[21][22][note 1] The empire rose to prominence as a culmination of attempts by the southern powers to ward off Perso-Turkic Islamic invasions by the end of the 13th century. At its peak, it subjugated almost all of South India's ruling families and pushed the sultans of the Deccan beyond the Tungabhadra-Krishna River doab region, in addition to annexing the Gajapati Kingdom (Odisha) up to the Krishna River, thus becoming a notable power.[23] The empire is named after its capital city of Vijayanagara, whose ruins surround present-day Hampi, now a World Heritage Site in Karnataka. The utter wealth and fame of the empire inspired visits by and writings of various medieval European travelers such as Domingo Paes, Fernão Nunes, and Niccolò de' Conti.

The empire's legacy includes monuments spread over South India, the best-known of which is the group at Hampi. Different temple building traditions in South and Central India were merged into the Vijayanagara architecture style, and this synthesis inspired architectural innovations in the construction of Hindu temples. Efficient administration and vigorous overseas trade brought new technologies to the region, such as water management systems for irrigation. The empire's patronage enabled fine arts and literature to reach new heights in Kannada, Telugu, Tamil, and Sanskrit, with topics such as astronomy, mathematics, medicine, fiction, musicology, historiography, and theatre gaining popularity. The classical music of Southern India, Carnatic music, evolved into its current form. The Vijayanagara Empire created an epoch in the history of Southern India that transcended regionalism by promoting Hinduism as a unifying factor[24]

Notes

- Dhere 2011, p. 243: "We can deduce that Sangam must have become a Yadava through his pastoralist, cowherd community.",

References

- The Mughal World, p. 386, Abraham Eraly, Penguin Books

- Cultural Sociology of the Middle East, Asia, and Africa p. 29, Andrea L. Stanton, SAGE

- "Patanjali", Wikipedia, 13 April 2023, retrieved 14 April 2023

- The Maurya Empire: The History and Legacy of Ancient India's Greatest Empire. Charles River Editors. 2017.

- Cultural Sociology of the Middle East, Asia, and Africa p. 29, Andrea L. Stanton, SAGE

- Angus Maddison (2007). Contours of the World Economy, 1–2030 AD. Essays in Macro-Economic History. Oxford University Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-19-922721-1.

- Building Bridges Among the BRICs, p. 125, Robert Crane, Springer, 2014

- Keay, John (2000). India: A history. Atlantic Monthly Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-87113-800-2.

The great era of all that is deemed classical in Indian literature, art and science was now dawning. It was this crescendo of creativity and scholarship, as much as ... political achievements of the Guptas, which would make their age so golden.

- "THE GUPTA EMPIRE OF INDIA 320-720".

- Padma Sudhi. Gupta Art: A Study from Aesthetic and Canonical Norms. Galaxy Publications. p. 7-17.

- Lee Engfer (2002). India in Pictures. Twenty-First Century Books. ISBN 9780822503712.

- "Patanjali", Wikipedia, 13 April 2023, retrieved 14 April 2023

- Angus Maddison (2007). Contours of the World Economy, 1–2030 AD. Essays in Macro-Economic History. Oxford University Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-19-922721-1.

- Angus Maddison (2007). Contours of the World Economy, 1–2030 AD. Essays in Macro-Economic History. Oxford University Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-19-922721-1.

- Building Bridges Among the BRICs, p. 125, Robert Crane, Springer, 2014

- Raghu Vamsa v 4.60–75

- Herausgeber., Kesavapany, K. Herausgeber. Kulke, Hermann Herausgeber. Sakhuja, Vijay. Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa : Reflections on the Chola Naval Expeditions to Southeast Asia (Tamil ed.). ISBN 978-981-4345-32-3. OCLC 1104856143.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - The First Spring Part 1: Life in the Golden Age of India. Penguin UK. 2014. p. 102. ISBN 9789351186458.

The period of the 'imperial' Cholas was the golden age of South India.

- Angus Maddison (2007). Contours of the World Economy, 1–2030 AD. Essays in Macro-Economic History. Oxford University Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-19-922721-1.

- Herausgeber., Kesavapany, K. Herausgeber. Kulke, Hermann Herausgeber. Sakhuja, Vijay. Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa : Reflections on the Chola Naval Expeditions to Southeast Asia (Tamil ed.). ISBN 978-981-4345-32-3. OCLC 1104856143.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Dhere 2011, p. 243.

- Sewell 2011, p. 22, 23, 420.

- Stein 1989, p. xi

- Stein 1989, p. 1.

Works cited

- Dhere, Ramchandra (2011). Rise of a Folk God: Vitthal of Pandharpur South Asia Research. Oxford University Press, 2011. ISBN 9780199777648.

- Radhakrishnan, S.; Moore, C. A. (1957). A Source Book in Indian Philosophy. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-01958-1. Princeton paperback 12th printing, 1989.

- Sewell, Robert (2011). A Forgotten Empire (Vijayanagar). New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-8120601253.

- Stein, Burton (1989). The New Cambridge History of India: Vijayanagara. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-26693-2.