Golden galaxias

The Golden galaxias (Galaxias auratus) is an endangered species of landlocked galaxiid fish belonging to the genus Galaxias. It is endemic to Lakes Crescent, Sorell, and their associated waterways located in central Tasmania, Australia.[1]

| Golden galaxias | |

|---|---|

| |

| Galaxias auratus (picture credit: Threatened Species Link) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Galaxiiformes |

| Family: | Galaxiidae |

| Genus: | Galaxias |

| Species: | G. auratus |

| Binomial name | |

| Galaxias auratus Johnston, 1883 | |

Description

The Golden galaxias are small scaleless salmoniform fish that typically grows from 140mm to a maximum of 240mm in length (tip of snout to tail). It has a thickset body with a long head, slender snout,[2] and the characteristic cylindrical trunk shared by other fish in the family Galaxiidae.[3] Its namesake comes from the distinctive golden-amber colouration and dark olive-green circular spots on its dorsal/upper surface; plus the dark ovoid markings on its sides. It has a silvery-grey colouration on its ventral/under surface postulated as a form of countershading camouflage.[1] The fins are amber to light orange in colour with black margins.[2]

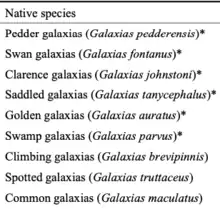

Phylogenetic relation to other Galaxias

The family Galaxiidae of which Galaxias auratus falls under, are restricted to the cool temperate regions of the Southern Hemisphere. Approximately 50 species can be found collectively in Australia, New Zealand, Chile, Patagonian Argentina, and South Africa. In South Australia alone, 5 genera and 22 species can be found with 91% of them being endemic. Galaxias can be characterised by morphological and phylogenetic differences as a result of biogeographical barriers. Freshwaters habitats along with land locking often isolate aquatic taxa leading to allopatric speciation events between Galaxias species.[3] Tasmania has significant galaxiid fauna and high endemism. Tasmanian inland waters are a stronghold for Australian galaxiids housing 5 genera and 16 species of which 11 are endemic. Galaxiids account for 64% of native freshwater fish species in Tasmania.[1]

Distribution

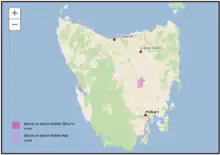

The Golden galaxias is endemic to Tasmania and can only be found in the interconnected Lake Crescent, Lake Sorell, and their associated waterways (an area less than 100km2).[2] Located in the central highland region of Tasmania, Australia. Currently, only four breeding populations exist including two natural and two translocated populations (established in the Clyde River catchment 1996- 1998).[1]

Habitat

The Golden galaxias is a non-diadromous species preferring freshwater habitats with still or gentle flow (lentic waters). They frequently feed in the water column but tend to be benthic, preferring the sheltered rocky lakeshores, lake beds, and wetland habitats.[1]

Diet

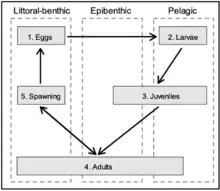

The Golden galaxias are opportunistic carnivores. The adult diet mainly consists of aquatic and terrestrial insects, small crustaceans, and molluscs; this includes cannibalism of eggs and juvenile fish. Juveniles are pelagic and feed in the water column foraging for zooplankton and small insect larvae.[1]

Reproduction, breeding and life history

Unlike most other galaxias species,[5] the Golden galaxias spawns from late autumn to winter at temperatures of approximately 4°C. This temperature change is associated with increasing lake levels signaling the optimum conditions to spawn. Rocky shores and wetland habitats found in Lakes Sorrel and Crescent provide suitable sheltered habitats for spawning.[1] Males become reproductively mature during their first year (at lengths over 50 mm), and females in their second year (at lengths over 70 mm). Records show that they have an average life expectancy of three to four years in the wild however, some individuals have been recorded reaching 6 years plus.[4] Each individual female can produce a clutch of 1000–15,000 small (1.5 mm diameter) eggs with their fecundity closely associated with their age and size. Eggs have a sticky coating that adheres to the cobble substrate or aquatic vegetation at depths of 200-600 mm in a scattered formation. Fertilized eggs incubate for around 30-45 days in the wild with peak larval hatching occurring during late winter to early spring. The newly hatched larvae are 5-7 mm in length and remain pelagic until they reach 4-5 months in age. They then migrate towards the inshore lake bottom habitat where they mature into adults.[1]

Status and conservation

Abundance

The latest natural population census indicates that populations of Golden galaxias in Lakes Crescent and Sorell are currently abundant. The relative abundance differs greatly between the two populations with Lake Crescent’s population being much greater than that of Lake Sorell's population. Two translocated populations located at farm dams in the Clyde River catchment are also currently abundant.[1]

Threats

Habitat loss, disturbance and modifications

The Golden galaxias' geographical distribution and endemism place the species in an especially vulnerable position to abrupt environmental change and human-induced habitat change. The genetic pool of the species is small; a result of isolation. The lack of genetic diversity could have negative implications for species survival. Anthropogenic activities in and around the lakes have increased pollution of the waterways and disturbed the habitats and waters occupied by the Golden galaxias. The building of dams across water bodies for hydroelectric power generation has contributed significantly to habitat loss resulting in further species decline.[1]

Low lake levels due to water extraction and climate change

The Golden galaxias are particularly sensitive to changes in water levels. Temperature change associated with increasing lake levels signals spawning and the low water levels can limit the availability of spawning habitats. This occurs as a consequence of dewatering which results in retreating rocky shores and wetland spawning habitats. The greatest threat to natural Golden galaxias populations is the low water levels in Lakes Crescent and Sorell.[1] Lake Crescent and Lake Sorell are designated reservoir sites supplying water to areas in the Clyde River valley. A prolonged drought event in the late 1990s and early 2009 resulted in record low lake levels aggravated by the extraction of water. This accelerated the deterioration of important habitat sites resulting in loss of habitat and increased disturbance. As a consequence, recruitment was poor over several breeding seasons leading to the species declining.[6] The increasing severity and prevalence of dry climatic conditions in recent years are predicted to impact the species negatively.[1]

Introduction of invasive species leading to competition and predation

The introduction of non-native fish has led to competition and predation on the Golden galaxias. There are four currently recorded introduced species that inhabit Lakes Crescent and Sorell.[1]

- Brown trout (Salmo trutta)

- Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss)

- Eurasian carp (Cyprinus carpio)

- Common galaxias (Galaxias maculatus)[1]

Two which pose a particular problem for the Golden galaxias are the Brown trout and Eurasian Carp. Brown trout are known to exclusively predate on Golden galaxias.[1] Prior to the introduction of the Brown trout, the Golden galaxias evolved in isolation from large predatory fish. It has been observed that they change their behavior to avoid predation however, this has had indirect impacts on their feeding, growth, reproduction, and habitat use patterns.[6] Eurasian carp (Cyprinus carpio) were thought to have been accidentally introduced to the lakes as baitfish. Since the 1990s, they have inhabited both Lake Crescent and Lake Sorell.[6] Their high fecundity and ability to produce a lot of eggs means that they outcompete the Golden galaxias for feeding, spawning, and refuge sites. The carp are ecosystem engineers that modify the waterways through their feeding style making habitats unsuitable for the Golden galaxias. Without control measures, the carp will eventually proliferate and displace native freshwater fish species as the dominant species.[7]

Fish containment screens

In 2001, a mitigation strategy to prevent the spread of Eurasian carp from Lake Sorell to Lake Crescent was implemented. Containment screens were installed in the waterway that connects the two lakes. These barrier screens use 5 mm mesh which unfortunately impedes the free movement of Golden galaxias between the lakes (with only the smallest individuals able to cross). The net divides the two Golden galaxias populations preventing gene flow from occurring across the populations. This has negative implications for the species' genetic diversity.[6]

Conservation measures and strategies

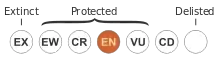

The Golden galaxias is a protected species under State legislation[1] and is currently listed as 'rare' under the Tasmanian Threatened Species Protection Act 1995.[5]

Habitat loss and disturbance conservation strategies

Conservation programs have attempted to increase the availability of Golden galaxias habitat sites by artificially creating rock habitats that meet the fish's feeding, refuge, and spawning requirements. Providing adequate habitat and reducing disturbance (through the careful monitoring of anthropogenic activities in or around the lake) has been shown to increase the survivability of the species, thereby allowing populations to rebound.[6]

Low lake water levels conservation strategies

Maintaining water levels above the critical minimum level in both lakes not only protects Golden galaxias habitats but ensures good water quality. During the spawning season, water releases are conducted by diverting the water supply toward spawning sites. This is especially critical for a successful spawning season in late autumn to winter. Water releases have been shown to benefit the survivability of offspring increasing annual population recruitment.[6]

Invasive species management strategies

Reduction and eradication programs have been implemented to control alien species population numbers and spread. The Tasmanian Carp Management Program is a positive example of an eradication program that has seen success. The program has purged the Eurasian carp out of Lake Crescent with the last carp caught in 2007. Currently, there are efforts to eradicate carp in Lake Sorell and avoid reintroducing the carp back into Lake Crescent.[6] Better netting strategies, technology, and the spread of a recent naturally occurring disease (called the “Jelly Gonad Condition” (JGC); which renders male carp sterile) have contributed to declines in the Eurasian Carp population.[8]

Raising public awareness

Education outreach programs raise public awareness about the plight of the Golden galaxias and their endangered status. Involving communities helps highlight the importance of this endemic plus, educating the public about invasive species reduces the chances of accidental translocation of an alien species back to Lakes Crescent and Sorrel. Such events instill the public with a sense of environmental consciousness and social responsibility. This leads to increased funding and exposure for conservation measures/strategies that will benefit the species.[6]

References

- Hardie, Scott (2007). "Conservation Biology of the Golden Galaxias (Galaxias auratus) (Pisces: Galaxiidae)". University of Tasmania PHD thesis. 1: 229.

- "Galaxias auratus – Golden Galaxias". Species Profile and Threats Database. Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities, Australia. 2013-07-16. Retrieved 2013-08-04.

- Waters, Jonathan (1997). "Aspects of the phylogeny, biogeography and taxonomy of galaxioid fishes" (PDF). University of Tasmania PHD Thesis. 1: 168.

- Australia, Atlas of Living. "Species: Galaxias auratus (Golden Galaxias)". bie.ala.org.au. Retrieved 2022-04-11.

- "Galaxias auratus (Golden Galaxias)". Threatened species & ecological communities. Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities, Australia. 2011-06-24. Retrieved 2013-08-04.

- "Conservation Advice Galaxias auratus (golden galaxias)" (PDF). Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999: 7. 16 December 2016.

- "The Carp Problem". carp.gov.au. Retrieved 2022-04-11.

- "Carp Management Program Annual Report" (PDF). Carp Management Program reports. 14: 32. 2020–2021.