Zichan

Zichan (WG: Tzu Ch'an) (traditional Chinese: 子產; simplified Chinese: 子产).[1] was a Chinese statesman living during the late Spring and Autumn period. From 544 BC until his death in 522 BC, he served as the chief minister of the State of Zheng. Also known as Gongsun Qiao (traditional Chinese: 公孫僑; simplified Chinese: 公孙侨,[2] he is better known by his courtesy name Zichan.

As chief minister of Zheng, a widely-respected state in central China, Zichan faced aggression from without and a fractious domestic politics. He led as Chinese culture and society was weathering a centuries-long period of turbulence, with governing traditions unstable and malleable, institutions battered by chronic war, and emerging new ways sharply contested. Under him the Zheng state prevailed and grew; he introduced strengthening reforms and met foreign threats. His statecraft was viewed with respect. Zichan was favorably treated in the Zuo Zhuan (an ancient text), and drew comments from his near-contemporary Confucius, later from Mencius.

Background

Zhou dynasty

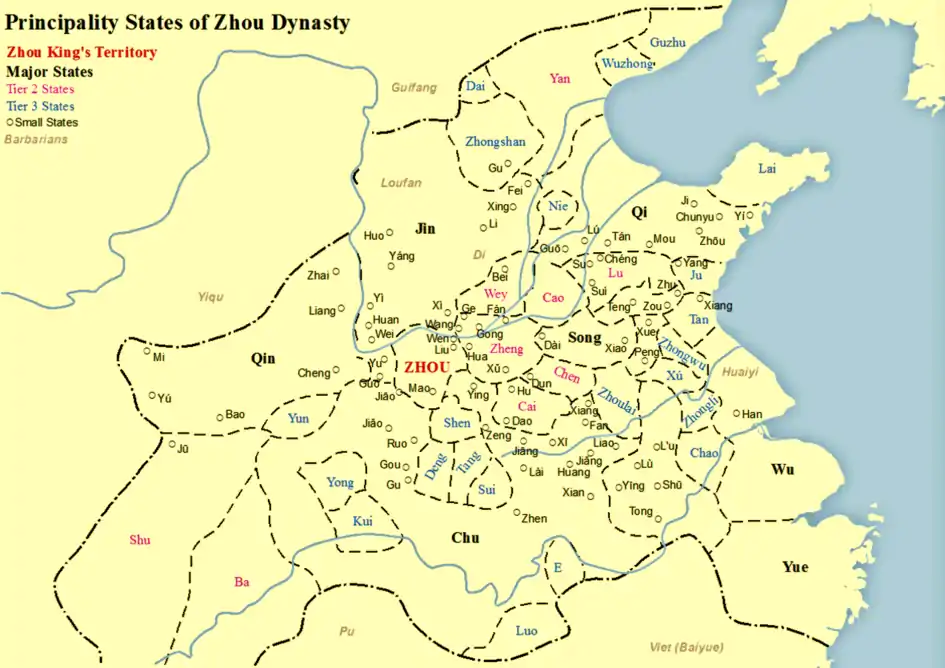

By its military defeat in 771 BC, historians divide the Zhou (c.1045-221 BC) into periods, Western and Eastern; as in retreat Zhou moved its capital east.[3] The dynasty not only never recovered, it steadily lost strength during the Spring and Autumn period (770-481 BC). At its start Zhou government used the fengjian system. Differing from the feudal, in the fengjian kinship was the primary bond between the royal dynast and local 'vassal'.[4][5][6]

State of Zheng

The founder of Zheng was Duke Huan (r.806-771 BC), a brother of King Xuan of Zhou (r.825-782 BC). The Zheng state by 767 BC had also moved east adjacent to the Eastern Zhou. Strategically located, Zheng prospered through trade. Duke Zhuang of Zheng (r.743-701 BC) defeated the Zhou king. He is compared to the Five Hegemons. Although its strength then declined, Zheng prospered and survived attacks by powerful neighbors. During the Warring States period (480-221 BC) in Zheng "the centre of the political stage was occupied by the competition between [its] clans". In that era's fierce rivalry between states, Zheng met its demise in 375 BC.[7][8][9][10]

Family of Zichan

Zichan was closely related to the rulers of the Zheng state, as a grandson of Duke Mu (r. 627-606 BC), and a nephew of Duke Cheng (r. 584-571 BC). Hence, he is also called "Ducal Grandson" Gongsun Qiao. He was a member of the clan of Guo, one of the Seven Houses of Zheng (the clans often competed for power). His ancestral surname was Ji, his personal name was Ji Qiao.[11][12][13]

In 565 BC Zichan's father, Prince Fa (Gongzi Fa), led a victorious campaign against the State of Cai. His military success, however, risked provoking the hostility of stronger neighboring states, e.g., Chu to the south and Jin to the north. Yet the Zheng leadership appeared pleased. Except Zichan, who said a small state like Zheng should excel in civic virtue, not martial achievement, else it will have no peace. Prince Fa (Ziguo) then harshly rebuked his son Zichan.[14] Shortly after the Cai invasion, Fa was assassinated by rival nobles of Zheng. Amid internal power struggles, Duke Jian of Zheng (r. 566-530 BC) began his reign.[15][16]

Career profile

| Part of a series on |

| Chinese legalism |

|---|

|

Reform programs

Zichan was responsible for many reforms that strengthened the state of Zheng. Directly involved in all aspects of the state, Zichan reformulated agricultural and commercial policies, reset the borders, centralized the state, ensured the hiring of capable ministers, and managed the evolution of social norms. He prohibited the public posting of writings and later also the deliver of pamphlets.[17] Yet also Zichan prevented another minister from executing a man for criticising the government, arguing that it was better for the state to listen to opinions from the common people.[18]

From writings of the subsequent Han dynasty historian Sima Qian, his Shiji:

Tzu-ch'an[19] was one of the high ministers of the state of Cheng. ... [T]he state [had been] in confusion, superiors and inferiors were at odds with each other, and fathers and sons quarreled. ... [Then] Tzu-ch'an [was] appointed prime minister. After... one year, the children in the state had ceased their naughty behavior, grey-haired elders were no longer seen carrying heavy burdens... . After two years, no one overcharged in the markets. After three years, people stopped locking their gates at night... . After four years, people did not bother to take home their farm tools when the day's work was finished, and after five years, no more conscription orders were sent out to the knights. ... Tzu-ch'an ruled for twenty-six years, and when he died the young men wept and the old men cried... .[20][21]

The Zuo Zhuan gives us a similar but different version of the public's appraisal of Zichan. After one year the workers complained about new taxes on their clothes and new levy requirements on the lands. Yet after three years the workers praised Zichan: for instructing their children, and for increasing the yield of their fields.[22]

The Zuo Zhuan records that he drafted penal laws to protect private property. He also enacted harsh punishments for criminals. Because of his focus on laws, historians often classify him as a Legalist.

The laws of 536 BC

_with_Interlaced_Dragons_LACMA_M.74.103a-b_(2_of_5).jpg.webp)

Context of legal act

In Zichan's reform of government one major focus concerned the law. Before Zichan, in each state the powerful hereditary clans, descendants of the Zhou lineage, had generally enforced their own closely-held laws and regulations.[23] The contents of the law might be known only to a "limited number of dignitaries who were concerned with their execution and enforcement." Laws "were not made known to the public."[24] "When the people were kept from knowing the law, the ruling class could manipulate it as it saw fit."[25] Yet the traditional governance among the city-states was then faltering and dissolving in continually changing conditions. In many regimes the ministers, by maneuver or ursupation, were replacing Zhou-lineage clan rulers in whose name they had acted. The ministers began to assume direct state rule of the population.[26] In 536 BC, Zichan had the legal statutes of his Zheng state inscribed on a bronze caldron or ding, and so made public, a first among the Eastern Zhou states.[27][28]

Au contraire, one modern view questions this notion that no state had published its laws before the late Spring and Autumn period. Creel raises doubts that laws were kept secret. He refers to the existence of earlier laws mentioned in ancient writings.[29][30] Creel mounts a direct challenge to several widely-quoted passages from the Zuo Zhuang that narrate: 1) how Zichan inscribed the Zheng laws on the bronze tripod ding in 536; and, 2) how Confucius criticized the similar publication of laws by a neighboring state in 513.[31]

Yet the story of Zichan being first to publish remains the modern consensus.[32][33][34][35][36][37] Zhao comments how the adverse political situation of Zheng "produced the legendary figure of Zichan, arguably the most influential reformer of his age. [Zichan's] most remarkable act was placing a caldron inscribed with Zheng's legal codes in a public place in 536". Judging by the fierce reaction generated, his action must have been considered "sensational at the time".[38] A law whose text was available to those subject to it, would work to foster their awareness of proper civic conduct. Published laws served the state, 1) as a way of guiding the people, and also 2) as a more effective tool of control, because it warns as well as legitimises punishment of violators. Zichan "had the complete support of the people of Cheng [Zheng], he enjoyed a position of full authority there throughout his life."[39][40][41][42]

Initial adverse reactions

For publishing the laws of Zheng, Zichan was criticized by some of his key contemporaries. It undermined the nobility, undercut their governing authority and their judicial role. Before, in making their legal judgments, the elite officials had applied to the facts their own confidential interpretation of what they viewed as the inherited social traditions. The end result of this shrouded procedure would be very difficult to challenge.[43] By articulating and making public the legal statutes the people were better empowered to advance an opposing view of state law. Up until then ruling circles thought publishing the law would be detrimental, would open the door to public argument, bickering, and shameless maneuvering to avoid social tradition, its time-tested moral force.[44][45] The situation was multi-sided, aa political roles were changing and the social tradition itself was in flux. Opening up laws to be viewed by the common people would eventually become a trend in ancient Chinese statecraft.[46]

Deng Xi of Zheng (545-501 BC), for good or ill, acquired a reputation for provoking social conflict and civic instability. A child when Zichan published the laws, Deng Xi was a controversial official of Zheng with Mingjia philosophical views.[47] Despite the probable corrosive activities of the Mingjia, Zichan in 536 had an historic bronze ding cast inscribed with Zheng laws, probably penal laws. As Deng Xi came of age, he challenged the state and its ministers, including Zichan.[48][49][50][51] Some thought he studied trickery.[52] The state of Zheng in 501 put him to death. Ancient documents are divided as to who ordered his execution. Most probably it was not Zichan.[53][54][55]

A long 'letter' faulting Zichan for making the law public, was written by Shuxiang a minister of Jin and personal friend of Zichan. It marshaled strong traditional arguments against his publishing the penal laws of Zheng. Harshly accusing Zichan of grave error, it predicted future calamity. Both the letter to Zichan and his reply are in the Zuo Zhuan. In response Zichan claims he's "untalented" thus unable to properly manage the laws with a view toward the future generations. To benefit people alive today was his aim.[56][57][58][59][60] Issues at stake here were long debated, e.g., by philosophers of the Warring States era that followed.[61][62]

Interstate relations

Zichan acted like a highly skilled realist in state-to-state politics. When the State of Jin tried to interfere in Zheng's internal affairs after the death of a Zheng minister, Zichan was aware of the danger. He argued that if Zheng allowed Jin to determine the minister's successor, Zheng lose its sovereignty. He eventually convinced Jin not to interfere in Zheng affairs.[63]

The Zuo Zhuan also mentions a summer meeting in 517 BC shortly after Zichan died. The Jin minister asked about ceremony and li (ritual propriety) of an official of Zheng, who then recounts a speech by "our former high officer" Zichan. The Zuo Zhuan quotes it at length. It is the book's "grandest exposition of ritual and its role in ordering human life in accordance with cosmic principles", according to the modern translators.[64][65][66] Feng comments on Zichan: "The idea expressed here... is that the practical value of ceremonials and music, punishments and penalties, lies in preventing the people from falling into disorder, and that these have originated from man's capacity for imitating Heaven and Earth."[67]

As a philosopher

Zichan's political thinking is known from his words and actions as a minister of state. The kernels of his thought are thus found in the historical record, often in accounts of his exemplary conduct. His near contemporary Confucius mentioned him. In the next few centuries following his death, several Warring States philosophers wrote of him, on occasion creating suggestive contexts for his points of view. Zichan's public life earned him renown in his lifetime and a lasting reputation in ancient Chinese political thought.[68][69][70]

Zichan lived in the Spring and Autumn period when "the old order broke down". The people "were bewildered by the lack of standards for settling disputes and maintaining harmonious relationships." The old hereditary houses lost cultural leadership, but the new regimes were fragmented, in constant conflict, and lacked the ready acceptance of customary authority. The era's instability led to an increasingly militant search for new social structures.[71][72]

Zichan is "depicted in the Zuo Zhuan as one of the wisest men of his time, [in his position] as leading statesman in Zheng". Zheng state was under almost constant existential threat from its rival city-states. In his person evidently Zichan practiced the traditional li ceremonies and elite virtues of the fading Zhou dynasty. In his politics, however, Han-era historians could see him as able to anticipate later Warring States-era Legalist philosophy, i.e., using newly articulated and promulgated standards to enforce state-wide obedience and so to better control events.[73]

The Zuo Zhuan quotes at length from the words spoken by Zichan. His thoughts tended to separate the distant domains of Heaven and the near domain of the human world. He argued against superstition and acted to curb the authority of the Master of Divination. He counseled the people to follow their reason and experience. Heaven's way is distant and difficult to grasp; while the human way is near at hand.[74][75][76]

Confucius

Confucius (551-479 BC) was almost 30 when Zichan died. Only in the generation after Zichan did Confucius, an unsuccessful office seeker, establish the literate tradition of an independent, private teacher in China.[78]

As a near contemporary, like Zichan, Confucius was "born in [this] period of great political and social change", a centuries-long revolutionary "upheaval caused by forces beyond his control and already under way." Prof. Creel notes scholarly speculation about the original sources Confucius used in his teaching; he comments that the Zuo Zhuan quotes at length "several statesmen who, living shortly before Confucius... expressed ideas remarkably like his." They were "advanced in their thinking".[79]

The Han historian Sima Qian lists Zichan as one of the six teachers of Confucius.[80][81]

There were, of course, issues on which Zichan and Confucius did not agree. Confucius, then only 15, did not comment when Zichan caused the laws of Zheng to be published in 536.[82][83] Yet when later in 513 the neighboring city-state of Jin published its laws, Confucius clearly made known his strong opposition. Such actions undercut the traditional authority of the Zhou-dynasty kings and the city-state nobles who ruled in their name, which scheme of governance Confucius consistently idealized.[84][85]

Another area of disagreement touched on the human capacity to draw insights from observing society. Confucius taught about an ability to discern, from today's repetition of civic events, the distant future. By careful observation, change in the customary rites of a dynasty can indicate the course of its social history many generations hence.[86][87][88][89] Zichan, however, at a decisive moment of political conflict, was known to confess thet he was not talented enough to make such future predictions. So he tailored his decision only for the people of Zheng then living.[90]

According to the Lunyu, Confucius nonetheless spoke well of Zichan. In his personal conduct and attitudes, Zichan seemed to represent the traditional virtues Confucius advocated.

The Master said of Tsze-ch'an that he had four of the characteristics of a superior man: in his conduct of himself, he was humble; in serving his superiors, he was respectful; in nourishing the people, he was kind; in ordering the people, he was just."[91][92]

The Lüshi paired Confucius and Zichan (who in this translation is called 'Prince Chan'). Both are praised as talented state ministers who led their countries to significant achievements. Both became widely regarded as successful governors who directed others to accomplish the tasks of administration.[93]

Mencius

The Mengzi of Mencius[94] refers to Zichan. A perplexed disciple questions Mencius about the conduct of Shun, one of the legendary sage kings. Shun's hostile parents and family lied to him. Shun mistakenly believed them, but he did not reveal a corrupt nature thereby. Shun believed their lies because of his regard for his parents. A life of virtue is then discussed.

Mencius compared sage king Shun here to an episode about Zichan, when he had believed a dishonest servant. Zichan had given his groundskeeper a live fish to keep in a pond; instead he cooked and ate it. He later told Zichan the fish was alive and swimming in the pond. Zichan was happy that the fish "found his place". Hearing this from Zichan, the servant mocked his reputation for wisdom. But not Mencius, who concluded: "Thus a noble man may be taken in by what is right, but he cannot be misled by what is contrary to the way".[95][96][97]

Yet Menzi in another episode disapproved of Zichan's 'small kindness'.[98]

Bibliography

Ancient

- Zuo Zhuan (Commentary of Zuo), concerning the Spring and Autumn period,[99] translated as:

- The Ch'un Ts'ew[100] with the Tso Chuen (London: Henry Frowde 1872; reprint Taipei 1983),[101] by James Legge;

- The Tso chuan. Selections from China's Oldest Narrative History (Columbia University 1989) by Burton Watson;

- The Zuo Tradition (University of Washington 1989), 3 vols., by Stephen Durrant, Li Wai-yee, David Schaberg;

- Zuo Tradition/Zuozhuan Reader. Selections (University of Washington 2020), by Durrant, Li, & Schaberg.

- Lunyu of Kong Fuzi, translated as Analects of Confucius: Legge (1861, 1893),[102] Waley (1938), Ames (1998),[103] Brooks (1998).[104][105]

- The Mengzi,[106][107] the Xunzi,[108][109] the Han Feizi,[110] wherein Zhanguo[111] philosophers refer to Zichan.

- Lüshi Chunqiu, translated as The Annals of Lü Buwei by Knoblock & Riegel (Stanford University 2001.[112]

- Shiji by Sima Qian: Two English translations[113][114] do not include the chapter (memoir) on Kong Fuzi.[115][116] Translations including it:

- Yang and Yang, Selections from Records of the Historian by Szuma Chien (Peking: Foreign Languages Press 1979), pp. 1–27;

- Richard Wilhelm, Confucius and Confucianism (New York: Harcourt, Brace 1931), pp. 3–70 (annotated).[117]

Modern

- Bodde, Derk and Clarence Morris, Law in Imperial China (University of Pennsylvania 1967).

- Ch'ũ T'ung-tsu, Law and society in traditional China (Paris: Mouton & Co. 1961).

- Creel, H. G., Confucius and the Chinese way (New York: John Day 1949, reprint: Harper 1960).

- Creel, Herrlee G., Shen Pu-hai. A political philosopher of the fourth century B.C. (University of Chicago 1974).

- Fung Yu-lan, Chung-kuo Che-hsüeh Shih (Shanghai 1931), translated as A History of Chinese Philosophy, vol. 1 (Princeton Univ. 1937, 2d ed. 1952, 1983) by Bodde.

- Graham, A. C., Disputers of the Tao. Philosophical argument in ancient China (Chicago: Open Court 1989).

- Hsu Cho-yun, Ancient China in transition. An analysis of social mobility, 722-222 B.C. (Stanford University 1965)

- Kaizuka Shigeki, Koshi (Tokyo 1951); translated as Confucius: His life & thought (New York: Macmillan 1956; Dover 2002), by Bownas.

- Lewis, Mark Edward, Honor and Shame in early China (Cambridge University 2021).

- Li Feng, Early China. A social and cultural history (Cambridge University 2013).

- Li Jun, Chinese civilization in the making, 1766-221 (New York: St. Martin's 1996).

- Lu Xing, Rhetoric in Ancient China (University of South Carolina 1998)

- Pines, Yuri, Foundations of Confucian thought: Intellectual life in the Chunqiu period, 722-453 (University of Hawaii 2002).

- Poo Mu-chou, In Search of Personal Welfare. Ancient Chinese religion (Albany: SUNY 1998).

- Rubin, Vitaly A., Ideologiia i kul'tura drevnego kitaia (Moscow 1970); Individual & State in Ancient China (NY: Columbia University 1976).

- Schwartz, Benjamin I., The World of Thought in Ancient China (Harvard University 1985).

- Sun Zhenbin, Language, Discourse, and Praxis in Ancient China (Springer 2015).

- Walker, Robert Louis, The Multi-state System of Ancient China. (Hamden: Shoestring 1953; Greenwood 1971).

- Zhang Jinfan, The tradition and modern transition of Chinese Law (Heidelberg: Springer 1997, 2d 2005, 3d 2008).

- Zhao Dingxin, The Confucian-Legalist State. A new theory of Chinese history (Oxford University 2015).

Articles

- Creel, Herrlee G., "Legal institutions and procedures during the Chou dynasty", in Cohen, Edwards, Chen (eds.), Essays on China's Legal Tradition (Princeton University 1980).

- Eichler, E. R., "The Life of Tsze-ch'an," in China Review (1886), vol. XV: pp. 12–23 & 65-78.[118]

- Fraser, Chris, "School of Names": Deng Xi (2015), in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Archive.

- Puett, Michael, "Ghosts, Gods, & Coming Apocalypse," in Scheidel (ed.), State Power in Ancient China & Rome (Oxford University 2015).

- Theobald, Ulrich, "Zichan" (2010), at ChinaKnowledge website, accessed 2022-07-27.

- Theobald, Ulrich, "Regional State of Zheng" (2000), at ChinaKnowledge website, accessed 2023-06-16.

- Turner, Karen, "Sage kings and laws in the Chinese and Greek traditions," in Ropp (ed.), Heritage of China (University of California 1990).

References

- In the Lŭchi Chunqiu (2000), p.818, Zichan is translated "Prince Chan".

- Kung-sun ch'iao [Wade-Giles]: Watson, Tso Chuan (1989) p.223.

- Li Feng (2013), pp. 160-161: fall of Western Zhou. Likewise Eastern Zhou divides into the Chunqiu and the Zhanguo periods (xx, 182).

- Zhang (2014), p.156: in the initial Zhou hierarchy "the imperial and the clan power were integrated." From social rankings, one can infer that "the clan power was the backbone of imperial power."

- Li Jun (1996): the fengjian system, pp. 67, 71-84; it desolves during the Eastern Zhou, pp. 103-108, 148.

- Goldin: Shen (2018), fengjian ranks: nobility Gong, aristocracy Dafu & Shi (116-118). In 770 Zheng ruler helped Zhou king move east (p.119).

- Theobald (2010), "Zheng": founding, move east, strategic location for trade and war; early hegemony; Zichan chief minister; annexed by Han.

- Li Feng (2013), 162-163: move east, early "the most active state".

- Li Jun (1996), pp. 104, 105 (quote per clans of Zheng).

- Goldin: Shen (2018), the Zheng state, p.119:"one of the most powerful" of the era's early states; tombs of Zheng lords excavated (1923); p.130: marketplace of Zheng; p.139: clothes.

- Theobald (2000), "Zichan": Dukes, his clan, his names.

- Pines (2002) p.313, lists Gongsun Qiao in his "Chunqiu Personalities", his cognomens: Zi Chan and Zi Mei.

- Kaizuka (1951, 2002), p.89: Zichan's family descendant from Duke Mu, but his clan was comparatively weak among Zheng's 'Seven Mu'.

- Zuozhuan (2020), Xiang 8.3, p.203. The editors comment (p.202): "Zixhan appears as a precocious child, much to the dismay of his elders, a common trope in early Chinese literature."

- Theobald (2000), "Zichan": victory and death of his father Gonzi Fa.

- Theobald (2010), "Zheng": "Zichan was a very competent person and was known for his kindheartedness, which helped him to survive the [violent politics] of the princes of Zheng."

- Sun (2015), p.15

- Lewis (2021), p.79 (praised by Confucius).

- 'Zichan' per the Wade-Giles romanization.

- Sima Qian, Shiji (1961), v.II, p.415 (quote).

- Confucius, when appointed chancellor of Lu by its ruler Ting (Duke Ding) was similarly described by this Han historian Sima Qian. Shiji (1979), p.8; Shiji (1931), p.23.

- Zuo Zhuan (2020), p.207 Xiang 30.13 (543 BCE).

- Liu (1998), pp. 50-53.

- Timoteus Pokora, "China," in The Early State (The Hague: Mouton 1978), edited by Claessen and Skalnik, p.206.

- Ch'u (1961), p.170. Ch'u then refers to and quotes Henry Maine's Ancient Law (11th ed, 1887), pp. 11-12.

- Li Jun (1996), pp. 102-120.

- Li Feng (2013), p. 174-175.

- Hsu (1965), pp. 14, 20-23.

- Creel (1980), pp. 34-38.

- Cf., Bodde and Morris (1967), pp. 11-17: discussion of early laws and Chinese theories of legal origins.

- Creel (1980), p.36: Zichan & laws of Zheng; p.37: Confucius contra.

- Lewis (2021), pp. 25-26 re Zichan, and Confucius in the Zuo Zhuang.

- Zhao (2015), pp. 164-165.

- Liu (1998), pp. 20-21: Zichan.

- Li Jun (1996), p.105: Zichan.

- Bodde and Morris (1967) pp. 14-16: Zichan (Tzu-ch'an).

- Ch'u (1961), p.170: "Not until the sixth century B.C. were laws of the various states revealed to the general public."

- Zhao (2015), p.164 (quotes: Zheng and Zichan).

- Walker (1953, 1971), quote at p.69.

- Kaizuka ([1951], 1956, 2002), p.106.

- Lunyu tr. Legge (1971), p.278 XIV:X.

- Zuo Zhuang tr. Watspm (1989), pp. 160-161.

- Kaizuka ([1951], 2002) pp. 79-80. Each clan ran its own legal affairs. Disputes between clans were decided ad hoc (case by case). This allowance to "clan autonomy" by the state was "idealized by later Confucian scholars [as] 'rule by virtue'" (p.80).

- Zuo Zhuang (2020), p.178 [Zhao 6.3], e.g., letter from Shuxiang, an official of the state of Jin.

- Cf., Fung (1937, 2d ed 1952, 1983), p.314: Confucius also attacked such notions of publishing laws.

- Schwartz (1985), pp. 323-330.

- "School of Names", at Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Annex, accessed 2022.12.12. The Mingjia was "notorious for logic-chopping". Although Deng Xi "established a link between disputation and litigation", it led to an anciently acceptable conclusion "that litigators disrupt social order and should be banned" (3.Deng Xi ¶1).

- Lu (1998), 128, 130-135: "Deng Xi made every effort to counter the suppression of ideas and opinions imposed by the rulers of Zhen." Lu relies on the Lu Shi Chun Qiu, yet here it was Zichan's authority that Deng Xi fought against (p.131).

- C.f., Lüshi Chunqiu (2000), p.453 {Bk.18, Ch.4.3].

- Creel (1980) p.41, where the suthor, on city politics of Zheng re Zichan and Deng Xi (WG Teng Hsi), quotes from the Lu Shi Chun Qiu:

When Tsu-ch'an governed the state of Cheng, Teng Hsi worked to make difficulties for him. He contracted with those involved in legal proceedings... . [Many people] gave him presents and studied lawsuits... . They held wrong to be right and right to be wrong, so that... the proper and improper changed every day. ... The state of Cheng was thrown into great confusion and the people clamored and wrangled. Tsu-ch'an was distressed by this, and put Teng Hsi to death and exposed his corpse. The people's hearts were then quieted, right and wrong were established, and law prevailed.

- Lüshi Chunqiu (2000), pp. 454-455 [Bk.18, Ch.4.4].

- The Xunzi (2014) harshly criticized Deng Xi, accusing him of using reason "to deceive and confuse the masses" (p.41 [6:48-50]), and of disregard for true right and wrong "in order to degrade and humiliate others" (pp.55-56 [8:118-120]). Hutton the translator refers to the Mingjia as "sophists" (p.204,n24).

- Zuo Zhuang (2020), p.180: at Ding 9.1 of year 501, the Zuo Zhuang states that the Zheng ruler Si Chuan put Deng Xi to death. Zichan, however, died in 522 (21 years before Deng Xi).

- Sun Zhenbin (2015), Deng Xi executed by Zheng's ruler (p.16) in 501 (p.14). Sun comments,"But the problems he raised were not solved by his death" (p.16).

- The Xunzi (2014), p.319 [28:42-43], without stating a date, narrates that "Zichan executed Deng Xi". This statement is the last on a short list given by Confucius (in the Xunzi) of six historic executions. It's context: Confucius himself had ordered an execution, then spoke of five reasons that justified putting a person to death (e.g., his "speaking falsely and arguing well" or his doing "what is wrong and making it seem smooth"). Confucius then gave his short list, the sixth and last being Zichan. Xunzi (2014), p.318-319 [28:21-47].

- Zuo Zhuang (2020), pp. 177-178 & 179 [Zhao 6.3].

- "I have not the talents nor the ability to act for posterity; my object is to save the present age". Legge's 1872 translation in E. D. Thomas, Chinese Political Thought (New York: Prentice-Hall 1927), p.229.

- Zhao (2015), pp. 164-165.

- Fung (2d 1983), pp. 313-314: Zichan's reply.

- Walker (1953, 1971), p.128: several decades later Jin state in 513 cast in bronze its own law on a tripod ding.

- Cf., Sun Zhenbin (2015), p.16, note 43: Deng Xi "aggravated the conflict between li and law."

- Some issues re the Fajia are addressed in Philosophy section.

- Lüshi Chumqiu (20o0), p.181.

- Zuo Zhuang (2020), p.128 (quote of Zheng official), p.127 ("grandest" quote), Zichan's speech at pp. 128-129 in 40 lines.

- Fung (1937, 2d ed 1952, 1983). Zichan's speech at pp. 38-39 in 45 lines. Fung includes it in his chapter "Philosophical Thought prior to Confucius".

- Watson (1989) does not translate this speech of Zichan.

- Fung (2d ed 1952, 1983), p.39.

- Schwartz (1985), pp. 325-327, 328 (portrayal of Zichan with regard to later legalism), 353 (reasoning versus the diviner's mythical view of comets).

- Rubin (1976), p.15: Zichan seen as "a statesman and thinker".

- Lewis (2021), p.39.

- Hsu (1965), p.53 quotes. In the late Zhou era, the nobility's once unquestioned rule antenuates, then falters. The emerging shih follows a traditional code (p.8) of status and loyalty, but their rulings begin to appear arbitrary, lose an effective hold on people. The state ministers begin to encroach on noblity's power, then to usurp their authority (pp. 1-8, 31-37).

- Li Feng (2013), pp. 161-178. After fall of Western Zhou (c. 771) the royal lineage systems were often eclipsed at the top by various hegemons. Then the xian system emerged: 'feudal' rule by Zhou nobility was replaced by state appointed local officials. The shih class arose. States explicitly began to employ legal codes to better control the population. During the Spring and Autumn period the cultural changes were "wide-ranging and fundamental", upheavals "totally reshaping" ancient China (p.161).

- Schwartz (1985), pp. 323-327, quote at 325. Schwartz notes that our texts about Zichan may reflect a subsequent legalist bias (p.325).

- Kaizuka ([1951], 2002), pp. 83-85.

- Schwartz (1985), re Zuo Zhuan: pp. 176, 177 (speech); p.181 (qi).

- Lewis (2021), pp. 27-28.

- Yang Zhaoming, A Tour of Qufu (Shanghai Press 2004, 2009), p.157.

- Schwartz (1985), p.60.

- Creel (1949, 1960), pp. 112-113 text, p.309 note 2. Creel emphasizes that the role of Confucius was "unique". He remarks that the similarity of the Analects with the possible "sources" might be a result of later text editing. For this interpretive theory Creel referred to unnamed scholars.

- Shiji (1994, rev'd 2021), vol. VII, p.115.

- Also: Lüshi (2000), p.713: Shiji quoted.

- Zuo Zhuan (2020), pp. 177-179 [Zhao 6.3].

- Lewis (1999), pp.20-21.

- Zuo Zhuan (2020), p.179 [Zhao 29.5].

- See discussion above: "Publishes laws (in 536)".

- Lunyu (1893), p.153 [II.23]: though "at a distance of a hundred ages, its affairs may be known." Legge notes that no "supernatural powers" are claimed (p.153).

- Lunyu (1998), p.114 [2.23]: Asked whether "ten generations hence could be foretold", Confucius noted factors to watch, concluding that "even though it were a hundred generations, it can be known." Brooks states no interpolation (p.329).

- Shiji (1925, 1931), pp. 54-55.

- Cf., Shiji (1979), pp. 21-22.

- Zuo Zhuang (2020), p.179 [Zhao 6.3].

- Lunyu (1893, 1971), p.178 (bk.V ch.XV). Also, Kung of Zichan: he gave government notices "proper elegance and finish", p.278 (bk.XIV ch.IX).

- Lunyu (1998), p.105 per 5:15 re Zichan ([here romanized as Dž-chǎn, cf.p2). Brooks & /Brooks state, however, this passage may be an interpolation (added at bk.13) made by Dž-Jīng (c.351-295). A rival (as an heir) to Mengzi (as a meritocratic challenger), Dž-Jīng was the fourth head of the Kung school at Lu (pp. 89, 99, 117 [rivals]; 145 [his death, his son repurposes school], 285, 287, 333 [Kung lineage & school]). Also Kung (Confucius) re Zichan's "elegance" p.120 (14:9).

- Lüshi (2000), p.390. Here the Lûshi articulates these positive appraisals in favor of Zichan and Confucius, yet does so in a convoluted manner to push a political argument.

- Fourth century (Warring States period).

- Mengzi of Van Norden (2008), pp. 118-120 [5A 2.1-2.4], esp. pp. 119-120 [2.4]. Van Norden notes that this "cognitive error" was considered "highly admirable" by Mengzi and much later by the Neo-Confician Zhu Xi as a form of "virtue ethics" (p.120).

- Mencius of Legge (1895, 1970), pp. 347-348 [V.II.4].

- De Barry and Bloom, Sources of Chinese Tradition, vol. 1 (Columbia University 1960, 2d ed 1999), p.143 (quote at end).

- Mengzi (2008), pp. 103-104 [4B 2.1-2.5]).

- Wade-Giles: Ch'un Ch'iu.

- Spring and Autumn Annals.

- Volume 5 of The Chinese Classics (Oxford University Press).

- James Legge, Confucius [texts] (Oxford: Clarendon Press 2d rev ed 1893, reprint Dover 1971).

- Roger T. Ames and Henry Rosemont, Jr., The Analects of Confucius. A philosophical translation (New York: Ballantine 1998).

- R. Bruce Brooks and A. Taeko Brooks, The Original Analects. Sayings of Confucius and his successors (Columbia University 1998).

- French: Couvreur (1895); German: Wilhelm (1921).

- Bryan W. Van Norden, translator, Mengzi, with selections from traditional commentaries (Indianapolis: Hackett 2008).

- James Legge, translator, The Works of Mencius (Oxford: Clarendon 2d ed 1895, reprint Dover 1970).

- Eric L. Hutton, Xunzi. The complete text (Princeton University 2014).

- Burton Watson, translator, Hsün Tzu. Basic writings (Columbia University 1963, 1996).

- Burton Watson, translator, Han Fei Tsu. Basic writings (Columbia University 1964).

- Wade-Giles: Chan Kuo.

- Michael Carson & Michael Loewe, "Lü shih ch'un ch'iu" at pp. 324-330 in Early Chinese Texts (SSEC & IEAS 1993), ed. by Loewe. Dated 239, ascribed to merchant Lü Pu-wei (d.235): a collection of new scholarly work and existing texts, comprehensive. German tr. by Wilhelm (1928).

- Records of the Grand Historian of China. Translated from the Shih Chi of Ssu-Ma Ch'ien (Columbia University 1961, two volumes) by Watson who begins with the Han dynasty (v.I, p.14).

- The Grand Scribe's Records (University of Indiana 1994-[2021], multiple volumes), edited by William H. Nienhauser, Jr.

- As to Nienhauser-edited volumes, see Revised Volume VII re The Memoirs of Pre-Han China (1994, 2021): Confucius not among the 28 here. C.f., p.xv: of 44 memoirs, 7 in volume I, and "9 more for future volumes" (apparently volume V.2).

- Cf., Kaizuka (1951, 2002), pp. 42-43: the Shiji chapter [#47] "The History of the Confucius Family".

- Wilhelm, Kung-Tse: Leben und Werk (Stuttgart: Frommanns 1925).

- Walker (1953, 1971), p.127, n.30: "The best work in a Western language" on Zichan.

- Chen Sen, "The age of territorial lords".

- Jue Guo, "The spirit world".

- Ori Tavor, "Religious thought".

- Yuri Pines, "Political thought".

- Roel Sterckx, "Food and Agriculture".