Gongylonema pulchrum

Gongylonema pulchrum is the only parasite of the genus Gongylonema capable of infecting humans.

| Gongylonema pulchrum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male Gongylonema pulchrum as seen under a light microscope.[1] | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Nematoda |

| Class: | Chromadorea |

| Order: | Rhabditida |

| Family: | Gongylonematidae |

| Genus: | Gongylonema |

| Species: | G. pulchrum |

| Binomial name | |

| Gongylonema pulchrum Molin, 1857 | |

Gongylonema pulchrum infections are due to humans acting as accidental hosts for the parasite. There are seven genera of spirudia nematodes that infect human hosts accidentally: Gnathostoma, Thelazia, Gongylonema, Physaloptera, Spirocerca, Rictularia. The G. pulchrum parasite is a nematode worm of the order Spirurida. It is a relatively thin nematode, and like other worms within its class, it has no circulatory or respiratory system. Most other Gongylonema species infect birds and mammals: there are 25 species found in mammals and 10 species found in birds.

This parasite is multi-cellular, and capable of movement. They have numerous rear mucosal projections, which assumedly assist propulsion through the thin layer of skin on the inside of the human host's mouth. They also have an excretory system possessing lateral canals. This parasite eats epithelial cells. Also, very often the canals are a place of inflammation, with accumulation of exudates in them. Gongylonema also swallows these exudates.

History of discovery

Gongylonema pulchrum was first named and presented with its own species by Molin in 1857. The first reported case was in 1850 by Dr. Joseph Leidy, when he identified a worm "obtained from the mouth of a child" from the Philadelphia Academy (however, an earlier case may have been treated in patient Elizabeth Livingstone in the seventeenth century[2]). He originally described it as Filariae hominis oris, and initially considered the worm was a guinea worm (Dracunculus medinensis), but because of the unique location of the worm (buccal cavity), and the relatively short size compared to the guinea worm, the hypothesis was disregarded. There have only been around 50 reported human cases of G. pulchrum worldwide since 1864, and these infections have been widespread and globally ubiquitous. G. pulchrum infections have been notoriously and historically hard to diagnose due to symptom complaints by patients (see "Symptoms" and "Diagnosis" below). Also, morphological diagnosis of the parasite is also somewhat complicated because of the variable size of adult worms, and the tendency of the worm to be different lengths depending on what host the worm is recovered from (see "Morphology" below).

Transmission

Transmission to humans is due mostly to unsanitary conditions and the ingestion of infected coprophagous insects, mostly dung beetles and cockroaches. Beyond direct ingestion of infected intermediate hosts (insects), foods can become contaminated if unsanitary conditions pervade in the production of the food- coprophagous insects are found in the food, or in the production chain. Also, contaminated water sources, again with the intermediate hosts or the infective third stage larva, can lead to transmission to humans. The infection usually occurs when someone drinks contaminated water, or consumes an infected beetle. The buccal mucosa, which is the ideal environment for the parasite, is the mucous membrane of the inside of the cheek. It is non-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium, and is continuous with the mucosae of the soft palate, the undersurface of the tongue and the floor of the mouth.

Reservoir and vectors

Gongylonema pulchrum, along with most other Gongylonema nematodes, has a broad natural host range. This includes hedgehogs, cattle, dogs, cats, ruminants, rabbits, and skunks. The vector and intermediate host for Gongylonema pulchrum infections are coprophagous insects (dung beetles and cockroaches).

Incubation

In humans, there can be an up to six week incubation period for worm development and symptoms may not appear until the second molting of the worm, in which the young adult worms begin migration from the esophagus to the buccal and oral palate tissue. It is this movement through the mucosa of the mouth and lips that causes patients to complain of symptoms. Gongylonema pulchrum burrows in the mucosal lining of the esophagus and other parts of the buccal cavity. There the 14 cm (5.5 in) females lay their thick shelled eggs containing first stage larvae. The larvae all possess a cephalic hook and rows of tiny spines around a blunt anterior end, so when they hatch they may further infest their hosts.

Morphology

The morphology of the worm is as follows, from a 2000 Veterinary Medicine study: "The anterior end in both sexes was covered by numerous cuticular platelets. There was a pair of lateral cervical papillae. The buccal opening was small and extended in the dorsoventral direction. Around the mouth a cuticular elevation enclosed the labia, and eight papillae were located laterodorsally and lateroventrally. Two large lateral amphids were seen. On the lateral sides of the female's tail, phasmidal apertures were observed. The caudal end of the male was asymmetrically alate and bore 10 pairs of papillae and two phasmidal apertures."[3] The average length for male worms is 29.1 mm (1.15 in), while the average length for adult females is 58.7 mm (2.31 in). The worm is highly mobile, as observed in patients’ mouths and as evidenced by the morphological design of the worm.

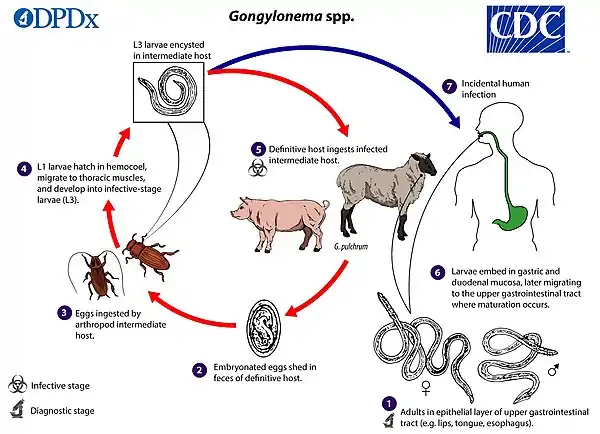

Life cycle

In humans, the hypothesized life cycle is as follows: Ingestion of contaminated food, water, or infected dung beetle. Infects upper esophagus, moves around and lays eggs in buccal cavity of human host, ingested eggs locate near esophagus, develop and mature into adult worms after two subsequent molting stages, migrate into buccal cavity, no eggs are ever found in human feces, which strengthens the assumption that humans are solely incidental, accidental, and dead end hosts for the Gongylonema pulchrum parasite life cycle.

The G. pulchrum parasite has also been studied in vivo in rabbits. The life cycle is as follows:

Infective third stage larva from naturally infected dung beetles (intermediate hosts and vectors), were orally given to rabbits. The larvae entered the upper gastrointestinal tract of the rabbits (esophagus and upper stomach), and then migrated upward into the buccal cavity- pharyngeal mucosa and tongue. A third molt took place 11 days after primary infection, and the final molt took place at 36 days after primary infection. Worms reached sexual maturity at about 8 weeks, and were found mostly in the esophagus of the rabbit. 72–81 days post primary infection, embryonated eggs appeared in the feces of the rabbits.

Symptoms

With initial infection, some patients have reported remembering a mild fever and flu-like symptoms about a month previous to extraction or identification of worm. The most common symptom is the complaint of sensation of a worm moving around the mouth, near the lips, and in the soft palate area. This movement is normally engendered by immature adult female worms. Symptoms, once noted, may continue from a month to a year if the worm is not surgically extracted. Eosinophilia is noted in some patients. Gongylonemiasis is the affliction caused by this parasite, which is simply protracted discomfort or sensation of movement in the buccal, oral or gingival areas associated with a sensation of foreign body. Subjects commonly pull worms from their gums, tongue, lips, and inner cheeks after days and even weeks of reported discomfort. In animals, this parasite quickly spreads down the esophagus, and into the upper digestive and respiratory tracts, making it more often than not, fatal. For humans, this parasite never makes it further than the oral cavity, and is often surgically or manually extracted.

Diagnosis

There is a danger of misdiagnosing infections of G. pulchrum as delusional parasitosis. Diagnosis is often made by visible recognition of the worm moving through the tissue of the buccal cavity by either patient or doctor. Also, recovery of worm from patient is also a diagnostic technique. Microscopic identification of worm removed from patient's mouth or tissue is another diagnostic technique for determining the parasite infection.

Treatment

Treatment for infections with G. pulchrum is surgical/manual extraction of the noticed worm and albendazole (400 milligrams twice daily for 21 days). Follow up measures include periodic checks of buccal cavity and esophagus to ensure parasite infection has cleared.

Epidemiology

Infections of G. pulchrum are not a huge public health concern. There have only been 50 recorded infections worldwide since the first reported case in 1850.[4] The infections of G. pulchrum have been widespread, and countries reporting human infections include the United States, Germany, Iran, Japan, Laos, Morocco, China, Italy, New Zealand, and Egypt, among others. Control measures for reducing infections include making sure vector and larval contamination of food and water sources does not occur- this could be included in basic sanitary practices. Another control measure is ensuring children and adults do not accidentally or purposefully ingest infected dung beetles and other coprophagous insects.

Case studies

In 1996, the first reported case of Gongylonema pulchrum infection was reported in Japan. A 34-year-old male complaining of irritable stomatitis on his lower lip went in to see his doctor, but the pain subsided spontaneously. However, it recurred several times in the next few months. When he went in to his doctor after one of these episodes, a thread like organism was seen protruding from his ulcer. The patient also had eosinophilia, but the ulcer healed with no scar once the organism was removed. The organism was identified as a female G. pulchrum worm, and the patient needed no further treatment.

How the patient contracted the worm is still unknown. He didn't report eating any abnormal foods, nor had he traveled outside Japan in the past few years. He also did not report drinking any water from possibly infected wells. It is possible that he ate food that had been contaminated in an endemic country and shipped to Japan. With the globalized food market now present, this is not out of the realm of possibility, and should be considered as a possible means of transmission into countries that have no previous history of G. pulchrum infection.[4]

In 1999, a 41-year-old female resident of New York City went in to her doctor complaining of the sensation of something moving in her mouth. She said she had had the feeling for the duration of one year. Supposedly, she had removed worms from her mouth on two separate occasions- one from her lip, and one from her gums. She submitted one of the specimens for microscopic identification, and it was found to be an adult female G. pulchrum worm. She traveled frequently to visit relatives in Mississippi, so it is unknown whether she contracted the worm in New York or in the south. This was the first reported case of Gongylonema in the United States since 1963.[5]

Also in 1999, a 38-year-old woman of Cambridge, Massachusetts sought medical attention for the visible identification of a “migrating mass” in her cheek mucosa. Six months earlier, she had noted an irregular patch of mucosa on her cheek, but thought nothing of it. Previously in the year, she'd traveled to Mexico, Guatemala, and France. She didn't report ingesting any beetles, but she did eat raw foods when vacationing in Mexico. She described the foods as “raw, crunchy, and saladlike”. Approximately 12 hours after eating the food, she and five other individuals she was traveling with had an acute attack of nausea, vomiting, and dizziness. The symptoms seemed to resolve themselves with no need of further treatment. A small female Gongylonema worm was surgically removed from her cheek mucosa under local anesthesia, and follow up treatment included albendazole two times daily for three days. This was the eleventh reported case of G. pulchrum infection in the United States. Most cases reported in the US are reported from the southeastern part of the country.[6]

There was a 1916 infection reported in a 16-year-old girl from Mississippi. She presented with gastrointestinal pain, vomiting and a low fever (101.5 °F (38.6 °C)). She complained of a sensation of a worm moving around her lower lip, but was disregarded by her physician. As she continued to complain, the physician examined her mouth, and discovered the outline of a worm. He extracted the worm with a sewing needle, and the child's complaints stopped and she appeared to have no further symptoms of parasite infection.

In 2013, the first case of human gongylonemosis was reported in France.[1] The patient, a healthy 48-year-old man felt the presence of a moving, worm-like organism in his mouth. Initially, the patient would occasionally feel, but not see, this mass at different sites: cheek, palate, gums and internal surface of the lower lip. The sensation would subside after several hours without leaving any visible lesions and without being accompanied by any associated localized or generalized symptoms. The patient had no medical history. He was a resident of Alsace, France, and had not travelled abroad. He reported not to have changed his lifestyle, especially not his diet, in the recent past. He also had no knowledge of having accidentally ingested an intermediate insect host. He consulted a doctor and all results of the clinical examination fell within the normal range. Haematology investigation revealed no abnormalities, particularly no elevated eosinophil count, and no microfilariae were seen using stained blood films; the filariasis serology was negative. No medical treatment was initiated. After 3 weeks of migration, the thread-like worm installed itself on the inner surface of the lower lip, allowing the patient to extract it by tongue pressure firstly, then using his fingers. He placed the parasite in alcohol and submitted it to a medical laboratory.

The parasite was the subject of a 2017 episode of the science documentary series Monsters Inside Me. Jonathan Allen, a biology professor and researcher at the College of William & Mary,[7] extracted the parasite alive from his own mouth and sent it for genetic testing after recognizing that it was not a parasite common to the United States; he is only the thirteenth known infected human in the country. Once he realized the lack of documentation of gongylonema infections in scientific literature, he and a colleague conducted further tests together with scientists from the Eastern Virginia Medical School and co-authored a paper published in the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene documenting the study.[8] Such is the rarity of human gongylonemosis that Allen's doctor failed to recognize the parasite, which Allen noted was due to so few documented cases in medical literature worldwide and the difficulty in diagnosing the infection due to its mild symptoms.[9]

Gallery

These are all pictures from a single Gongylonema pulchrum male extracted from a man in France.[1]

Entire male

Entire male Head

Head Posterior end

Posterior end Precloacal papillae

Precloacal papillae Postcloacal papillae

Postcloacal papillae Right spicule and gubernaculum

Right spicule and gubernaculum Complete plate (click on image for detailed caption)

Complete plate (click on image for detailed caption)

References

- Pesson, B.; Hersant, C.; Biehler, JF.; Abou-Bacar, A.; Brunet, J.; Pfaff, AW.; Ferté, H.; Candolfi, E. (2013). "First case of human gongylonemosis in France". Parasite. 20: 5. doi:10.1051/parasite/2013007. PMC 3718519. PMID 23425508.

- O. Weisser, Ill Composed: Sickness, Gender, and Belief in Early Modern England (London, 2015), p. 25.

- Naem, S (2000). "Scanning Electron Microscopy of Adult Gongylonema pulchrum". Journal of Veterinary Medicine, Series B. 47 (4): 249–255. doi:10.1046/j.1439-0450.2000.00347.x. PMID 10861193.

- Haruki, K., Furuya, H., Saito, S., Kamiya, S. & Kagei, N. 2005: Gongylonema infection in man: A first case of gongylonemosis in Japan. Helminthologia, 42, 63-66. Free PDF

- Eberhard, Mark; Buillo, Christopher (1999). "Human Gongylonema infection in a resident of New York City" (PDF). American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 61 (1): 51–52. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.1999.61.51. PMID 10432055. S2CID 13404446.

- Wilson, M (1 May 2001). "Gongylonema Infection of the mouth in a resident of Cambridge Massachusetts". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 32 (9): 1378–1380. doi:10.1086/319991. JSTOR 4461603. PMID 11303277.

- "Faculty of Arts & Sciences — Department of Biology: Faculty". College of William & Mary.

- Allen, Jonathan D; Esquela-Kerscher, Aurora (October 2013). "Gongylonema pulchrum infection in a resident of Williamsburg, Virginia, verified by genetic analysis". American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 89 (4): 755–7. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.13-0355. PMC 3795108.

- "Scientist researches parasite that he removed from his own body". College of William & Mary. October 1, 2013.

Further reading

- "Gongylonema". GIDEON Infectious Diseases. 1994–2010.

- Ward, Henry B (March 1916). "Gongylonema in the Role of a Human Parasite". Journal of Parasitology. 2 (3): 119–125. doi:10.2307/3271194. JSTOR 3271194. S2CID 84002989.

- Garcia, Lynn Shore (2001). "Gongylonema". Diagnostic Medical Parasitology. 4.

- Kudo, N (2005). "Further Observations on the Development of Gongylonema pulchrum in Rabbits". Journal of Parasitology. 91 (4): 750–755. doi:10.1645/ge-3441.1. JSTOR 20059757. PMID 17089739. S2CID 21208376.

- Lichtenfels, JR (1971). "Morphological variation in the gullet nematode, Gongylonema pulchrum Molin, 1857, from eight species of definitive hosts with a consideration of Gongylonema from Macaca spp". Journal of Parasitology. 57 (2): 348–355. doi:10.2307/3278041. JSTOR 3278041. PMID 5553452.

- Kirkpatrick, CE (1986). "Gongylonema pulchrum Molin in Black Bears from Pennsylvania". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 22 (1): 119–121. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-22.1.119. PMID 3951047.

- Uni, S.; Abe, M.; Harada, K.; Kaneda, K.; Kimata, I.; Abdelmaksoud, N. M.; Takahashi, K.; Miyashita, M.; Iseki, M. (1992). "New record of Gongylonema pulchrum Molin, 1857 from a new host, Macaca fuscata, in Japan" (PDF). Annales de Parasitologie Humaine et Comparée. 67 (6): 221–223. doi:10.1051/parasite/1992676221. ISSN 0003-4150.